Carlos Marreiros sits at the head of the meeting table in his office within the beautiful Albergue – he speaks quickly, mindful that he needs to leave soon to attend the opening of the MGM Cotai, a new addition to the architectural landscape in Macao. Cigarette in hand, he takes us on an architectural journey through the decades in Macao.

Marreiros, a trained architect and city planner, founded MAA Marreiros Architectural Atelier Ltd. in 1999. Not content to limit his passion and creativity to architecture, Marreiros is also a university professor, painter, writer, poet, and government consultant for the city’s heritage preservation and urban planning committees.

Over the years, he has been awarded numerous distinctions for his work, including the title of Great Official of the Order of Prince Henry by then president of Portugal, Jorge Sampaio, in 1999, and the Medal of Professional Merit of Macao in 2002.

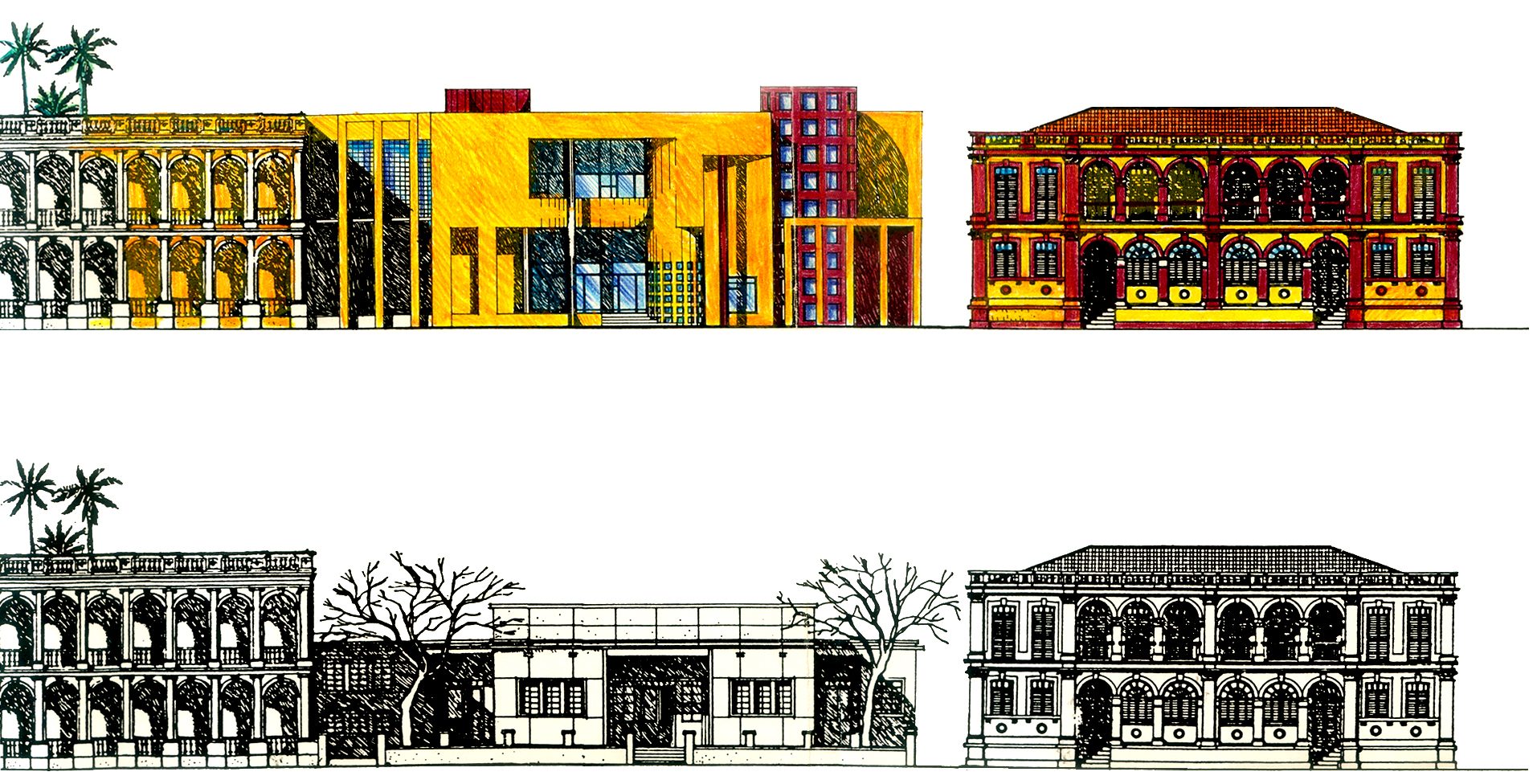

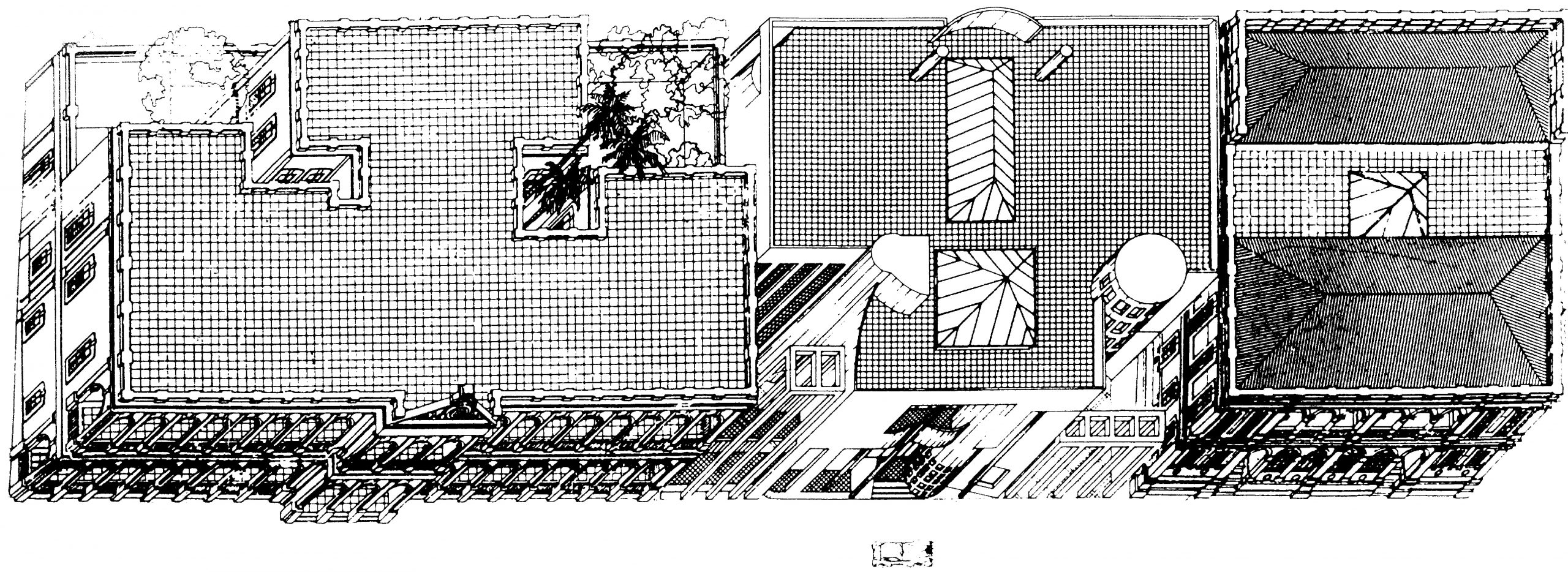

While his architectural work can be found throughout Macao, Marreiros is most proud of Tap Seac Health Centre (1991), Tap Seac Square (2007), and the Macao Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo 2010.

How would you describe Macao’s architecture pre‐ and post‐1999?

The construction boom in Macao started in the ‘70s. At the time, there were one‐ and two‐storey buildings and villas with gardens all along the riverside of Praia Grande, and even in the inner part of the Macao Peninsula. These were not only houses for rich families; they were for middle class people.

So when buildings started to be six‐storeys high, it was already impressive. Then the Rainha D. Leonor building was completed in the 1960s, this very elegant 12‐storey building with duplexes, located in

the centre of Macao. It became a landmark, a delicate blade imposing itself on the tranquil urban profile of the peninsula. It appeared in all of the photos and postcards of Macao from the ‘60s, but today, it’s completely obscured by surrounding buildings.

So there was a shift in scale?

Definitely. The demography was changing; the population grew and their purchasing power increased. That was the very beginning of the first construction boom of Macao, and it intensified over the next two decades.

Naturally that meant buildings got even taller in the ‘80s and ‘90s – some as many as 40‐storeys high – changing the city’s landscape. Some of the bigger venues, such as the Macau Cultural Center and the Macao Museum of Art on the new reclamation area of NAPE, were built in the last decade or so before the handover.

After 2004, with all of the investment brought in by the gaming liberalisation, Macao changed dramatically in terms of both money and scale. The money flooding in kicked off a second

construction boom, altering Macao’s profile completely. Such growth was inevitable; however, it could and should have been managed through a master plan.

Before, the Macao Peninsula was dominated by the Hotel Lisboa, completed in 1970. Its architectural features were so specific, so unique, that nobody could date it – it could have been of the ‘50s or even the ‘30s. After its completion, some traditional Macao souvenirs opted for depictions of the hotel instead of the iconic Ruins of St Paul’s, adopting the new hotel–casino complex as a symbol of modern Macao. The first Macao–Taipa bridge, designed by Edgar Cardoso, was also considered a symbol of modernity.

At the time, Taipa and Coloane were the future of Macao in terms of urban expansion. Cotai – a combination of Coloane and Taipa – was designed in the ‘90s to house a satellite city of about 200,000 people. Although many were sceptical, I defended it as the future of Macao. Today, that land is the goose that lays the golden eggs.

We also have the old peninsula with the main historic centre and other sites that are not yet part of the UNESCO World Heritage List, but are worth being defended and inscribed, like the Inner Harbour or the area of São Lázaro and Tap Seac.

Today, when you approach the Macao Peninsula from the sea, you will see the Macao Science Center – a building from after the handover – and then the Grand Lisboa, which is a striking building. Again, difficult to date with its strange morphology, but no one can be indifferent when looking at that building. It is iconic by its eccentricity. Then you have the MGM, One Central up to Our Lady of Penha Chapel, where you still have a backdrop of some heritage in the romantic Praia Grande Bay.

Some of the structures you just listed are on the UNESCO World Heritage List while others are very modern. Do you think they’re compatible with each other?

Yes, they are compatible.

As you know, I’m a heritage preservationist; I’ve dedicated all my life to heritage preservation. But heritage is not static, it must coexist with contemporary architecture. You can see this all around the world, historical and modern in balance with one another.

In Macao, there are areas where this balance has not been reached because the land is too expensive and the lots are too small; there isn’t always a good return on investment. This leads many to maximise the area of construction, resulting in buildings that are too compacted and tall. Despite these contrasts, I still think Macao is a city with soul, and that is the most important thing for a city to have.

You can have a beautiful city like Brasilia in Brazil, designed by two of the best international architects using the best knowledge and technology available, and it will still lack soul until people create it.

The soul of Macao has been consolidating for over 450 years. People are sometimes shocked with the unbalanced massing of the buildings and the difference of scales, yet Macao is still a vibrant city with a strong identity.

Do you believe the lack of space in Macao will pose a problem for future architectural projects?

In Macao’s future plans there are 350 hectares to be reclaimed on both sides of the river, on the peninsula’s southern edges and the northern part of Taipa, as well as the artificial island, where the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge lands before reaching Macao. In the beginning, a lot of people were against this land reclamation. I stand for it because reclaiming land is in the DNA of Macao; it’s been part of the city since the very beginning.

Reclaiming land is in the DNA of Macao; it’s been part of the city since the very beginning.

Carlos Marreiros

Even the old settlement of Macao was consolidated on the mud within the Inner Harbour. Think of Rua da Praia do Manduco and all that area from Rua de Cinco de Outubro to Rua dos Faitiões – it was all consolidated by bamboo and timber piles before the embankment.

Do you see any other potential roadblocks?

We have to cultivate the right environment to develop good architecture. Before the handover, you had big investments in cultural, social, and infrastructure projects in Macao – the port of Macao, the government hospital, social housing, schools, cultural centre, and so on.

After the handover, there’s still investment in social and cultural construction, but the quality of design and construction have gone down. For architecture to be considered notable, it’s not only the question of budget but also elements such as functionality, sustainability, urban contextualisation, and the innovative use of design and technologies.

The current architecture has to meet community needs, to be more than just a building, but without the type of budget found in the gaming industry. We need talented local architects and designers to do it well. Unfortunately, the current architectural design doesn’t offer much in the way of the so‐called signature design architecture.

For a place – a city, a region, a country – to have good architecture, you need a tripod of elements. The industry has to be composed of good architects and engineers – if you don’t have good designers of the related disciplines, you don’t have good architecture – and you must have good developers and contractors, as well as good clients to accept innovative approaches. Lastly, there are official licensing departments for building and construction authorities that must respond competently to this process. If one of these legs is missing, the whole structure falls down.

To some degree, we also rely on the user as well, and the people of Macao are good. If you explain it well, with honesty, they may have some complaints but will largely accept new ideas and experiences.

Do you think it’s worth developing architectural tourism in Macao?

Not yet. In terms of heritage, of course, it has been successfully developed but always in the shadow of the casinos.

Hopefully now that Macao is a UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy, more people will take in the city’s food and heritage offerings as well as the casinos. Even before the title, Macao had been a paradise of food for a long time. People from Japan, Hong Kong, and mainland China came to Macao for food all the time. This new title is an opportunity to build on what we have, to take on a more visionary approach by incorporating the urban architectural heritage, gastronomy and, I hope, other ways of culture into tourism promotion.

So you think the heritage is ready for that kind of tourism but in terms of contemporary architecture, it’s not ready?

In terms of contemporary architecture tours, not yet. There are cities that many people visit solely for enjoying contemporary architectural tours, but Macao is far from reaching that level. Right now you have some contemporary buildings which people might be interested in visiting: the Zaha Hadid building at City of Dreams is definitely the most exciting for me, and there’s the new MGM Cotai, StarWorld or Altira in Taipa. These are very well‐designed buildings, but not enough to bring people to the city.

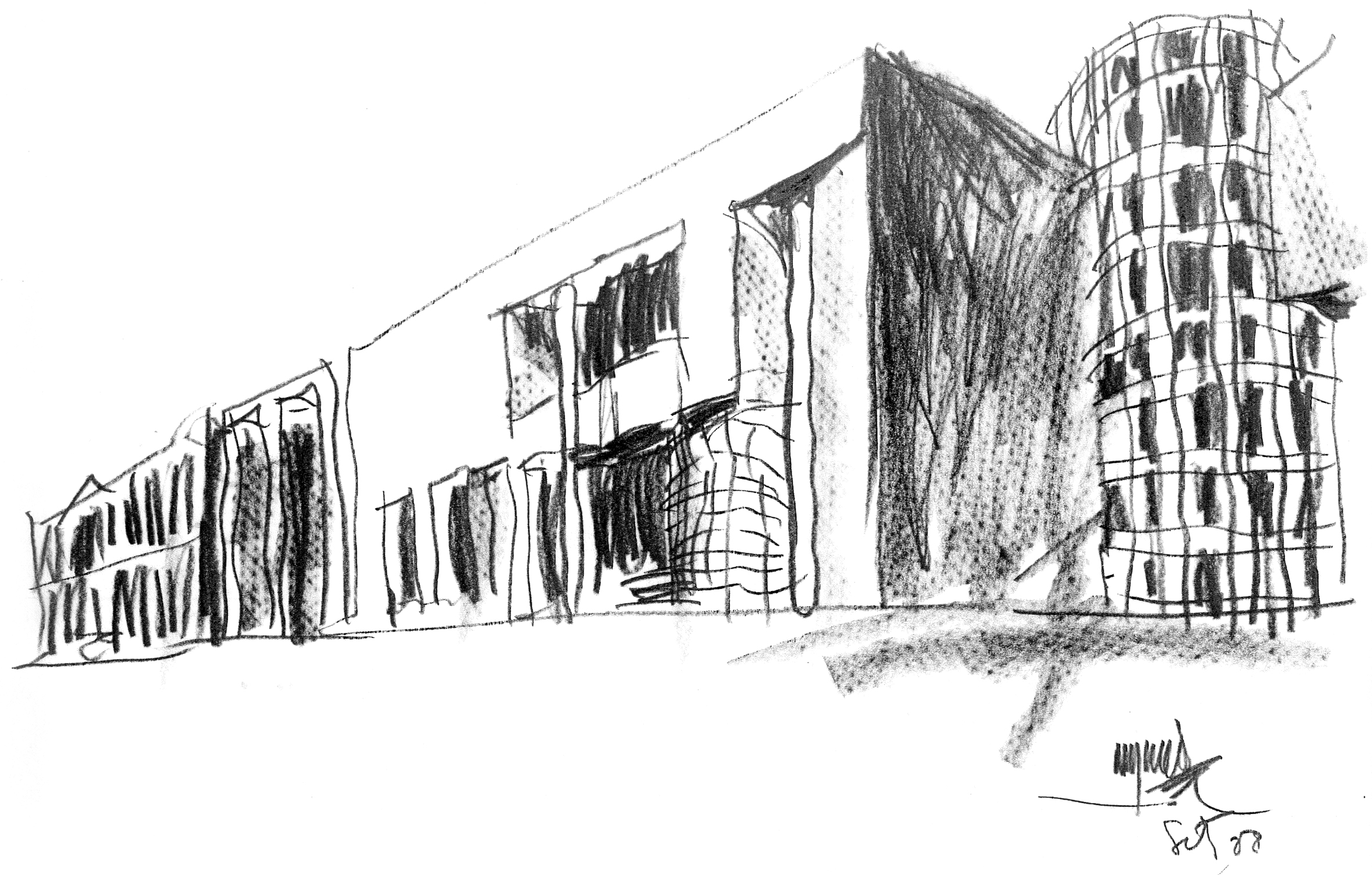

My great hope is to also see local architects designing buildings that are of higher quality, advanced in technology and with identity. Globalisation is fantastic – bringing people together, in real‐ ‐time information, with real‐time solidarity – but at the same time, we have to be careful about making the world too much the same.

For example, there are some fashion brands whose corporate image building is beautiful and very well designed. But it’s the same in Tokyo, in Hong Kong, in Shanghai, in Milan, in New York – that’s boring!

In the past, high‐quality architecture – simple, innovative works, often achieved without a big budget – was produced in Macao. You had Júlio Alberto Basto, a very modern Art Deco architect working from the ‘30s up to the ’60s, and Chan Kuan Pui and José Lei Meng Kan, modernists as well. Then with the boom in the ‘60s and ‘70s, you had Raúl Chorão Ramalho or even Manuel Vicente, a young architect at the time, then José Maneiras and others.

So you think that Macao needs more quality in the design of everyday architecture?

Yes. Buildings used by residents – whether for leisure, culture, sports, education, or social gatherings – should be original and environmentally friendly, even on smaller budgets. Excellent designers from abroad could team up with local firms, updating local designers’ skills and creating new high‐quality architecture for Macao. Likewise, we should expand the more cutting‐edge architectural and urban experiences beyond buildings associated with gaming to include some facilities which serve the community.

But for Macao to become a true city of contemporary architecture, it must also invest more in the quality and quantity of urban spaces. It’s too crowded. Moving towards more open and covered urban spaces, interconnected with pedestrian bridges, greenery and related infrastructure, will make the city more inviting and balanced.

Money from gaming changed the architectural practice in Macao a lot, but the industry also introduced a more organised administrative process and a new culture of construction. You see it in the construction sites: they’re clean and well organised. You didn’t have that before. The organisation of the process – taking the project from schematic to development and construction to works in progress on site – is a great achievement for Macao brought by the gaming industry.

But in terms of contemporary and cutting‐edge architecture, what was brought by gaming is not yet the best, with a few exceptions. We should invite more innovative thinkers, planners, designers of the most avant‐garde structures, to design projects in Macao. We also need to involve the local firms, giving them more opportunity to get in touch with top designers

and even exchange experiences abroad. This is what China has been doing in the last few decades with great success.