Did Marco Polo plot his path to China using an atlas? This question was posed at a recent cartography seminar in Macao, held to mark the unveiling of the city’s “Mapmorphosis” exhibition. “Mapmorphosis”, hosted by the Orient Foundation at the historic Casa Garden, displayed large-scale maps pulled from across the past five centuries – all featuring Macao.

While the 34 exhibits aren’t the fragile and often lost originals (many of those were destroyed during the 1755 Lisbon earthquake), these printed reproductions still convey the artistry, science and spirit of adventure required from cartographers of yore. They also serve as a visual chronicle of Macao’s geographic history. The maps illustrate how the territory slowly became better understood over time, how its urban and oceanic landscapes have evolved, and the tripling in landmass that’s taken place over the past hundred years.

As for Marco Polo, seminar attendees learned that no, the explorer was not in possession of a map when setting sail from Venice in 1271. Given the nascent state of cartography at the time, he relied on local knowledge to navigate the Mediterranean, pass through Constantinople, reach Crimea and set off overland through Central Asia and the Gobi Desert to finally arrive in Beijing.

Some 150 years later, accounts of Marco Polo’s travels served as foundations for a new wave of navigational maps in Europe. The Portuguese prince known as Henry the Navigator was at the helm of this revolution – through his maritime research centre, the School of Sagres. He aimed to improve cartographical knowledge, equip sea captains with reliable maps, and extend Portugal’s reach around the world. Henry the Navigator’s vision, backed by considerable wealth, enabled the Age of Exploration.

“With every voyage, our picture of the world changes,” the exhibition organiser, Marco Rizzolio, said at the “Mapmorphosis” opening. “With every voyage, the map becomes increasingly accurate. The map is an instrument of power.”

Macao’s history through maps

The first European to reach China by sea, via the Pearl River Delta, was Jorge Álvares, a Portuguese explorer whose statue stands tall near Macao’s Nam Van Lake. While Álvares dropped anchor in Macao in 1513 (meaning the territory likely began featuring on European charts of the region shortly after), the oldest map in “Mapmorphosis” hails from the 1570s.

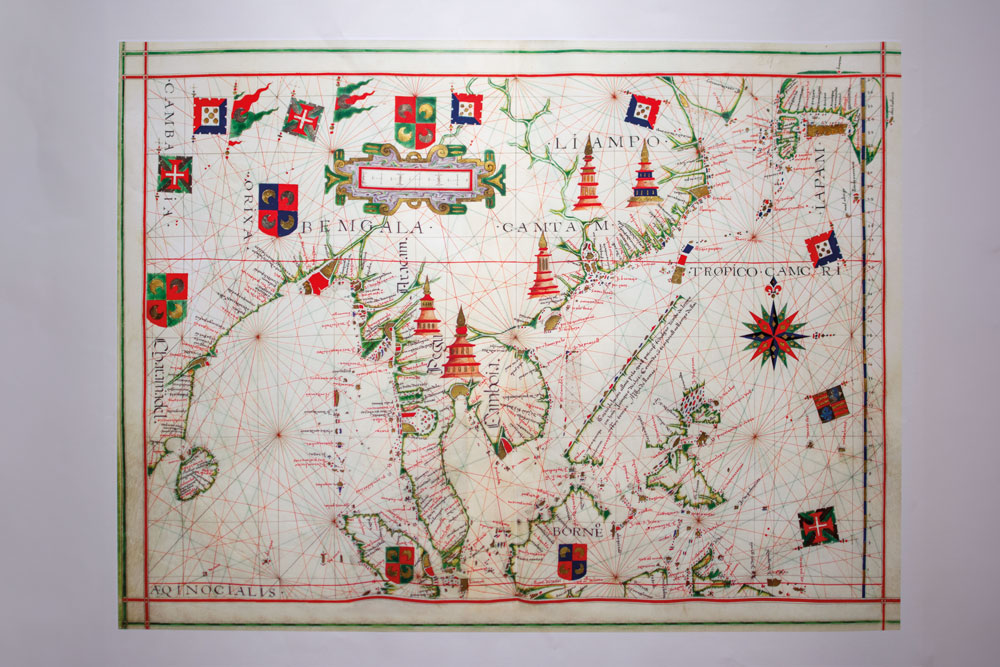

Mapa Mundo, as it’s called, was an ambitious attempt at depicting Asia, with India on the far left and a barely recognisable Japan on its right. Macao is just a dot along the ‘Cantam’ (Canton) coastline, somewhere above an incomplete outline of Borneo. The map is credited to Fernão Vaz Dourado, a highly respected Portuguese cartographer based in Goa, India, for most of his life.

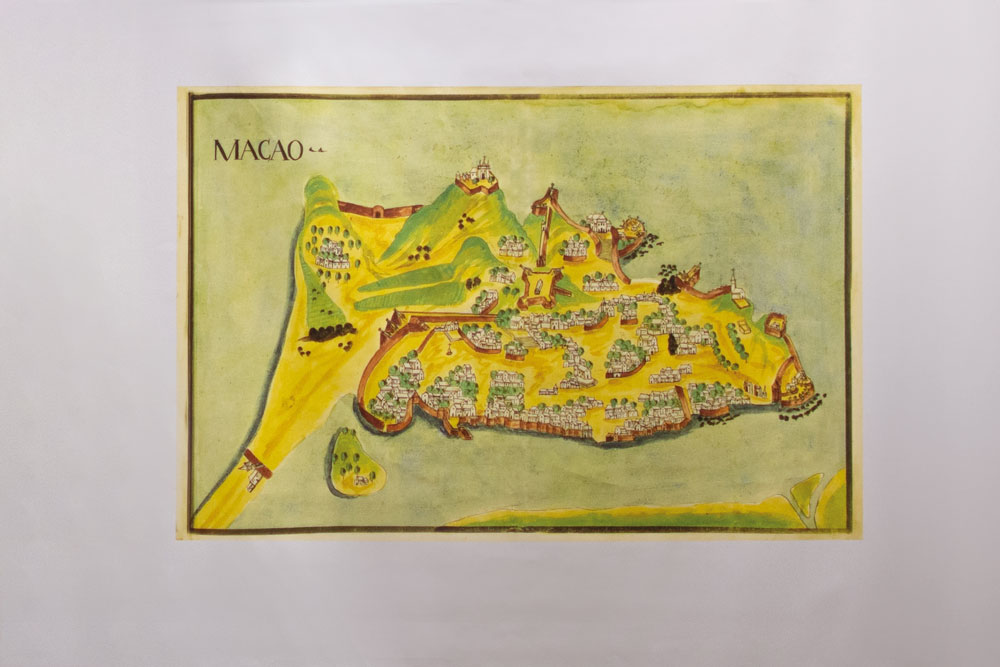

Offering more insights into Macao’s character at the turn of the 17th century – though limited guidance to navigators – is a pictorial map made by the Flemish engraver Theodore de Bry. Titled Amacao, this stylised depiction of urban Macao stretches to each edge of a territory almost surrounded by sea (there’s a slender stalk peeling off to the left; its attachment to the mainland). Amacao’s cartographic usefulness lies more in essence than geographical precision. It captures the territory’s alive-to-this-day East-meets-West reality while imparting basic spatial intel about Macao.

At first glance the city appears European, peppered as De Bry’s work is with churches and Portuguese caravels. There’s a large cross standing in a courtyard: this territory is clearly Christian. But closer examination reveals men rowing dragon boats through choppy seas, and people moving beneath umbrellas held aloft by servants – common practices in parts of Asia at the time. There’s also a sedan chair, a Chinese form of transport that didn’t reach Europe until decades later, and several buildings with tiered, hip-and-gable roofs (implying pagodas).

More geographically accurate detail arrived in 1635, via a Portuguese cartographer named Pedro Barreto de Resende. His vivid watercolour showed a heavily fortified city with protective walls around its coastlines. Monte Fort – built in 1626 – is visible inland and bristling with canons. The fortifications were a bid to fend off maritime attacks after a heated period of Dutch bombardment.

A very similar map to Resende’s formed part of the Casa Garden exhibition. This one, attributed to the official cosmographer to the Portuguese crown, António de Mariz Carneiro, is almost a stroke-for-stroke copy of Resende’s original (minus a few decorative ships and a cross on a hill). It was published in 1639.

By the end of that century, European cartographers from beyond Portugal were developing a keener sense of what Macao looked like through firsthand experience of the land. One of these was the young explorer François Froger, part of an early French voyage to China in the 1690s. Froger – who wrote extensively about his travels and also sketched prolifically – created a refined map of Macao Peninsula with a key depicting its 10 main features. There’s a Chinese village in the territory’s northeast, both the Monte and Guia forts, and a wall separating Macao from “les terres des Chinois” (Chinese lands). Froger’s map is one of the earliest to note the ancient A-Ma Temple, on the peninsula’s southwestern flank (where it still stands today). The temple is labelled “pagode Chinoise”.

Most early maps ignore Macao’s southern islands, which didn’t come under Portuguese administration until the mid-1800s and lacked major settlements. They started appearing more prominently near the end of the 1700s, mainly as navigational features. The waterway between the islands (now fused through land reclamation) was labelled “Typa” and the islands themselves were named according to what side of the Typa they were on.

The English cartographer and sailing master William Bligh provided more insights into the islands in his 1781 map of Macao, offering tips to future navigators. “If going into the Typa, keep the south shore on board … then steer for Shoal Point and anchor in 4 fathoms water,” Bligh advises (his words are actually printed on the map). He also noted sections of sea that were dry at low tide and where reliable sources of fresh water could be obtained.

Bligh got his information firsthand while accompanying the British explorer James Cook on his 1780 voyage around the Pacific. Less than a decade later, he rose to fame as captain of the HMS Bounty and was at the heart of the ship’s infamous mutiny in the South Pacific. After being overthrown by his crew, Bligh and a few loyal sailors embarked on a harrowing journey of almost 7,000 kilometres that landed them in Timor. Events of the mutiny have been well-preserved in popular culture through literature and film adaptations.

Changes on the ground

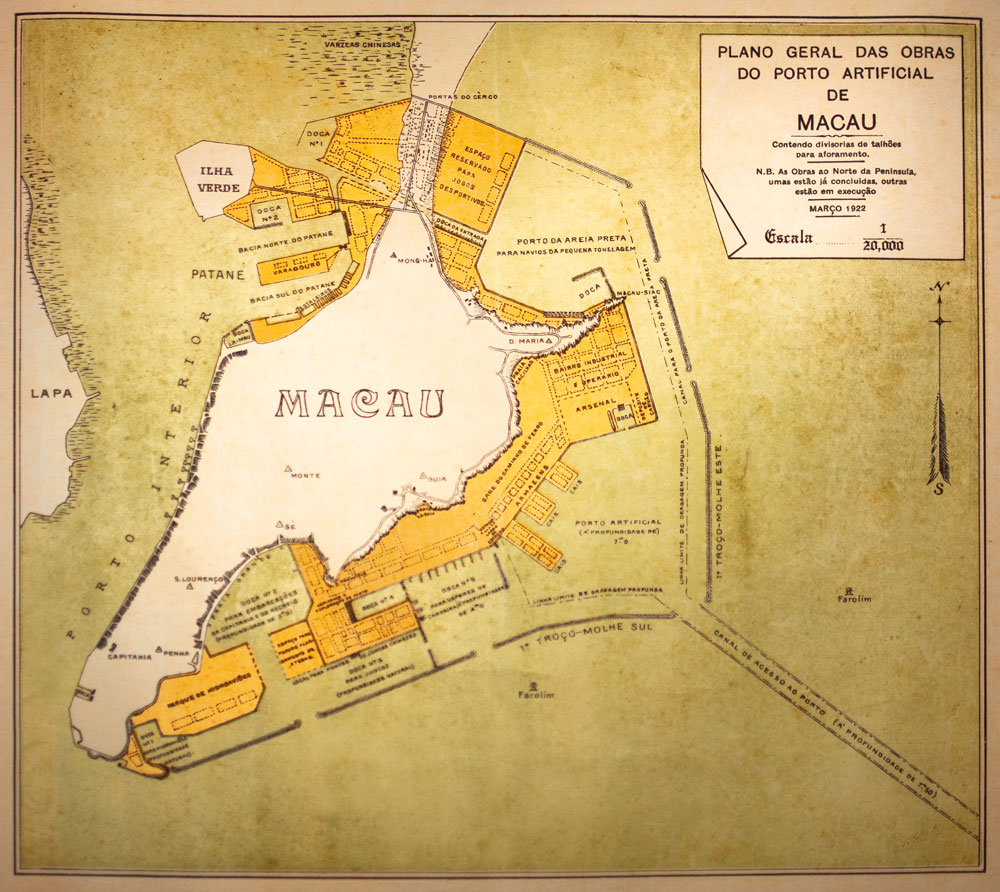

Up until the mid-1800s, the quite dramatic variations in Macao’s size, shape and appearance depicted in maps stemmed from ever-improving knowledge of the region (helped along by technological advancements). However, changes that followed were the result of intentional modifications to the land itself. In 1912, Macao’s total area was a mere 11.6 square kilometres; it has since expanded to more than 33 square kilometres.

In the exhibition, a large-scale chromolithographic map from 1889 shows Ilha Verde as an island to the city’s northwest. Maps produced less than a decade later, however, reveal a narrow causeway tethering it to the Macao Peninsula. Over time, this causeway expanded due to land reclamation, erasing any trace of Ilha Verde’s insular nature. The area, its name translating to ‘green island’ in Portuguese, has since completely merged with the mainland on its north and eastern sides, and with Macao to its east.

A parallel phenomenon can be seen via what started out as a slim isthmus connecting Macao to the mainland. The territory’s earliest maps show their boundaries defined by a collar-like structure: the Border Gate. However, as land reclamation efforts broadened the isthmus, the Border Gate stopped stretching from one coast to the other.

Perhaps one of the most interesting maps in the exhibition was the deceptively simple Plano Geral das Obras do Porto Artificial de Macau, from 1922. It foreshadows extensive land reclamation works planned for the city at the time – some of which, like the Outer Harbour and Nam Van Lake developments, would not be completed for many more decades.

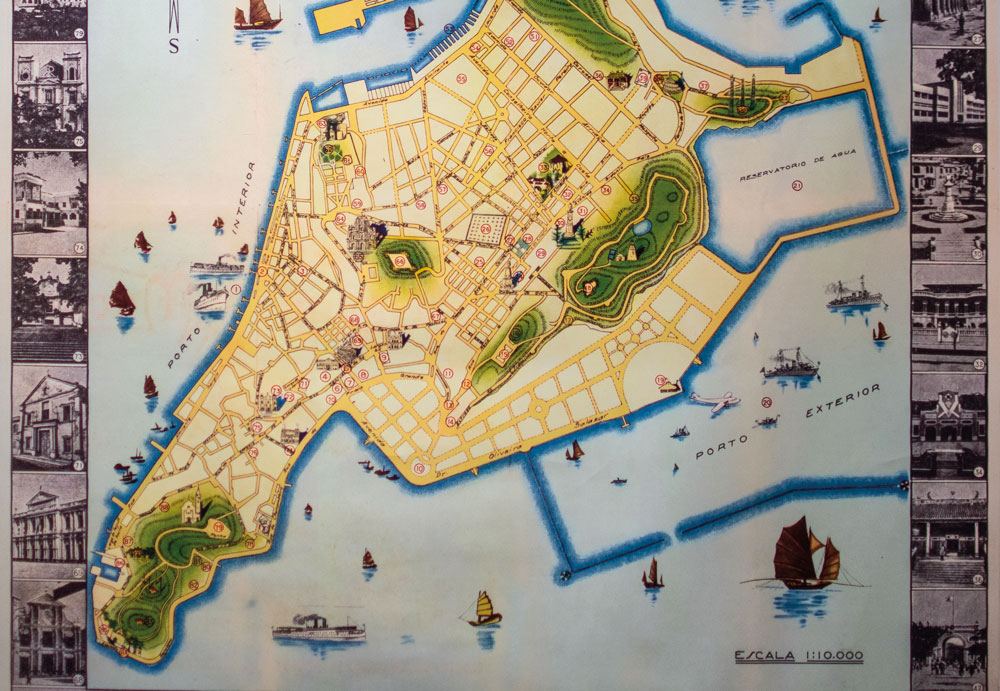

A 1936 travel map produced by Macau Agencia de Turismo, meanwhile, reveals how the process of getting to and from Macao had evolved since the days of heavily rigged merchant vessels. The map includes illustrations of steam ships, and also a Pan American seaplane – ‘moored’ at Macao’s once-famous seaplane port (now reclaimed land around today’s Fisherman’s Wharf).

‘Wonderful just as objects of art’

The maps featured in “Mapmorphosis” are more than tools designed to get a person from A to B. “They really are quite wonderful just as objects of art,” the historian Priscilla Roberts said during the exhibition’s opening seminar. The University of St. Joseph professor is right: the maps are beautiful. Each one crafted by a team of talented artisans.

Some have been delicately daubed with pastel hues, others shot through with bold bolts of green and red. They capture a myriad of ways to depict Macao’s many churches. Tiny sailboats and patchwork fields are exquisitely rendered, along with emblems signifying the European empire responsible for each map. Some maps are stripped down and minimalistic, like Froger’s. Others are joyfully maximalist, a riot of colour and illustration. But all are elegant; created with care.

Making a map in the 17th century required enormous amounts of scarce resources and skilled labour. It was an incredibly expensive merging of global exploration, science, craftsmanship and art. First, came the surveys, carried out by cartographers, navigators, travelling merchants and sailors. Just getting to the location in question was hard, typically involving months’ (even years’) long voyages across often unfriendly seas. Given the purpose of cartographic missions was to produce better maps of an area, existing maps were usually flawed.

In situ, geographic details would be collected via journals, ships’ logs and sketches. Distances between settlements and elevations of hills might be hazarded using the likes of astrolabes and primitive theodolites, but a lot of information came via word of mouth and observation. None of it as reliable as, say, satellite imagery and a GPS.

A cartographer would then collate everything he could into what’s known as a ‘manuscript map’. These were meticulously detailed drafts, hand drawn on parchment or vellum. Manuscript maps tended to include illustrations – a rocky shoreline, a fort with cannons – to offer an accurate visual sense of the landscape. They’d also feature the odd sea monster and other ornate embellishments.

Macao was known for producing high-quality manuscript maps during the Age of Exploration, which were shipped off to Europe for printing and reproduction. To print a map in those days, an engraver traced a mirror image of the cartographer’s design onto a flat copper plate and poured ink over the heated metal. Excess ink would be wiped off, leaving just enough of it sticking to the copper plate’s finely etched lines. Pressing the plate down onto slightly damp parchment (or whatever material was being used) imprinted a facsimile of the cartographer’s original work. The colourist’s job came next: he’d typically use watercolours to make a map’s various geographical elements pop. The same copper plate was then re-used to produce copies of the map, though each one required fresh ink and colouring.

“The skill, the knowledge, the expertise that went into these [maps in the exhibition] is extraordinary,” Roberts noted. Not only have most original maps from prior to the 19th century not survived, they were rare to begin with, she explained. “Those maps required so many hours of painstaking labour, time consuming craft and – not uncommonly – expensive, hard-to-find materials that you simply don’t have many of them.”

Roberts believes the “Mapmorphosis” exhibition goes beyond showcasing Macao’s cartographical history. She sees it as honouring the commitment and craftsmanship of bygone mapmakers: “The many individuals who created works of art that are both elegant and beautiful but also extremely practical, fixing geographical knowledge in the historical record for future generations to see and appreciate.”