Brazil received more Chinese money than anywhere else in the world during 2021, according to a study by the Brazil-China Business Council (CEBC). The study, released in August, reveals Chinese companies invested US$5.9 billion (MOP 47.5 billion) into South America’s largest economy last year; more than triple 2020’s numbers and a return to pre-pandemic levels of investment. Brazil’s oil and gas sector was the standout beneficiary, receiving 85 per cent of total investment.

Titled “Chinese Investments in Brazil: 2021, A Year of Recovery”, the CEBC study also reported US$70.3 billion (MOP 566 billion) flowing from China into Brazil between 2007 and 2021, making it the fourth largest recipient of Chinese money for that period. As Chinese spending in markets other than Brazil fell dramatically over 2021 (by 70 and 27 per cent in Australia and the US, respectively) Brazil rose to the top. It’s followed by the Netherlands, Colombia and Indonesia.

Meanwhile, Brazilian exports to China reached US$87.9 billion (MOP 708 billion) last year – a more than 150 per cent increase from 2016, according to Brazilian Ministry of Economy data. Almost half of its exports were agri-products, making for a record high in spite of the Covid-19 pandemic. Chinese exports to Brazil, while also growing, were worth a more modest US$47.6 billion (MOP 383.5 billion).

CEBC Content and Research Director Tulio Cariello told Macao magazine that the two countries’ economic relationship is structurally sound and ripe for intensification due to complementary needs and resources.

China has an enormous demand for mineral, energy and agricultural commodities, for instance – areas where Brazil is highly competitive. Brazil is also one of few countries with the capacity to produce and export large volumes of these commodities.

Cariello noted that the countries’ trade relationship is qualitatively uneven. “This reflects, on the one hand, the great Chinese competitiveness in sectors with higher added value, and on the other hand, that Brazilian industry suffers from heavy taxes and a relative complacency caused by protectionist measures,” he explained.

“Chinese Investments in Brazil” shows Chinese investors are mainly involved in Brazil’s oil and gas sector. Last year, major oil exploration projects in the pre-salt region of Santos Basin and Búzios field were negotiated between the country’s state-run oil firm Petrobas and two Chinese companies: China National Oil and Gas Exploration and Development Company and China National Offshore Oil Corporation. Other sectors that drew Chinese interest were information technology, electricity and vehicle manufacturing.

Cariello said there was plenty of scope to explore further opportunities, too. Brazil has considerable bottlenecks in technology and infrastructure development, while China has a great deal of accumulated experience in both. “There is also space for a ‘market fit’ in sectors such as construction, transport and logistics, in addition to great synergy in projects aimed at sustainability, such as low-carbon agriculture and livestock,” says Cariello.

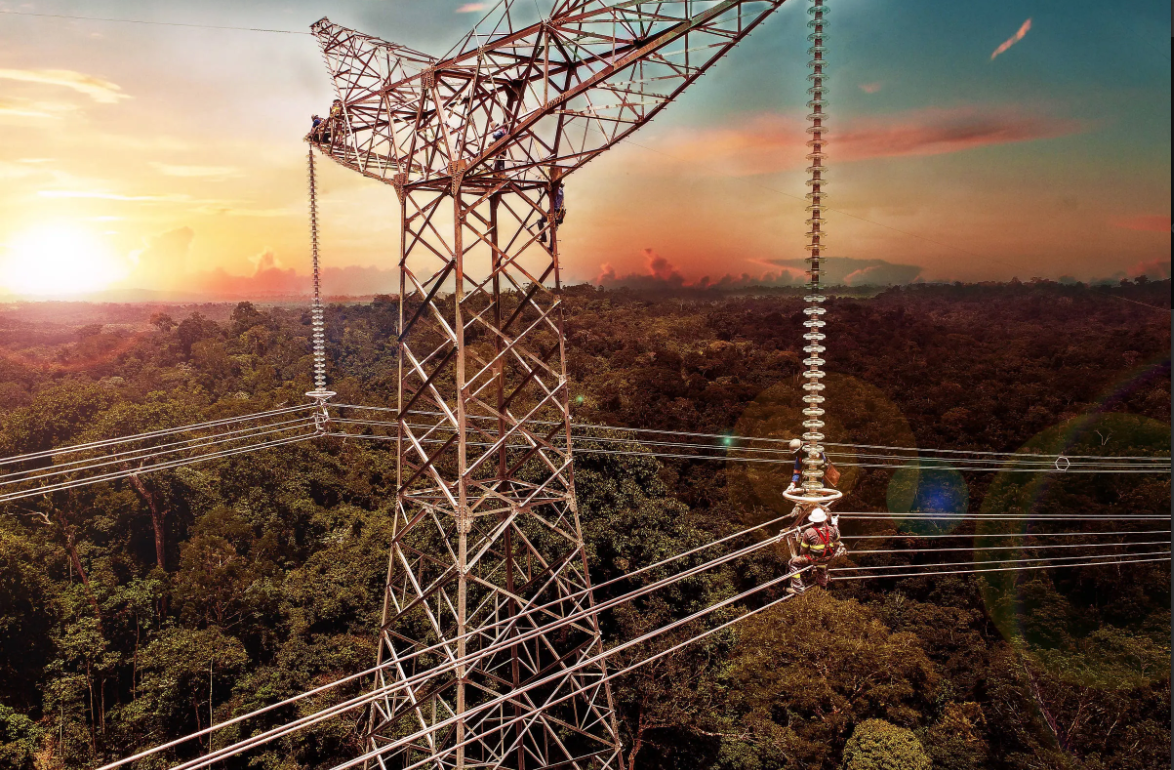

Representatives from three large Brazilian subsidiaries with Chinese holding companies attended the study’s release party: China Three Gorges (CTG) Brasil, Banco BOCOM BBM, and Great Wall Motors Brasil. José Renato Domingues, corporate vice-president of CTG Brasil, spoke of how China’s state-owned power company’s relationship with the South American country dates back 30 years. He recalled company technicians travelling to Brazil in the early 1990s to study the massive Itaipu hydroelectric plant, across the Paraná River, which was completed in 1984. The Chinese technicians wanted to understand what was then the world’s biggest hydro dam before they started building the Three Gorges plant in China, which overtook Itaipu in electricity output in 2020. CTG established its Brazilian subsidiary in 2009, sensing that “Brazil has to invest in energy to continue growing,” Domingues said.

A growing trade relationship

While Covid-related restrictions in China have caused shipping delays in recent years, trade generally kept its pace – and with Brazil, increased. One indicator that trade ties between China and Brazil are deepening is that the Sino-Brazilian High-Level Coordination and Cooperation Commission is now headed by China’s vice-president (it was formerly headed by the vice-premier). Both countries are part of the BRICS alliance of emerging economies, named for the first letter of each member country: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Cariello said that recent growth in Brazil’s exports to China came down to a combination of factors. The trade disputes between the US and China ended up benefiting Brazilian producers – especially in the agricultural sector – who stepped up to bridge the gap. China’s African swine flu outbreak led to surging demand for imported meat, which Brazil was able to supply. Pandemic-related supply shocks caused some Brazilian commodity prices to rise, which in turn brought greater financial returns even when volumes were down. Cariello notes that Brazil is one of few countries in the world with a trade surplus with China – nearly US$40 billion (MOP 322 billion).

Brazilian exports to China are largely agricultural and mineral goods, namely oil, iron, soy and meat. Selling agricultural products to China is such a driving force for the Brazilian economy that the country’s Ministry of Agriculture recently created a specialised task force for the Chinese market. Almost all Chinese exports to Brazil, meanwhile, fall into the machinery, electronic appliances, and consumer goods categories. Due to the conflict in Ukraine, Brazil has also been importing more Chinese fertilisers.

“Today, unlike two decades ago, we import not only low value-added industrial products, but also more sophisticated products from China,” said Cariello. “I believe we will see this trend broadening in the coming years, given the innovations in the Chinese industry.”

The road ahead: Electric Vehicles, mergers, and premium exports

Better matching Brazilian needs with Chinese expertise could open up significant opportunities for both economies, Celio Hiratuka, coordinator of the Brazil-China Study Group and professor at the Institute of Economics at Unicamp (the State University of Campinas), told Folha Press. Several major investment projects in areas such as sustainability, energy, urban mobility and digital transition are already underway.

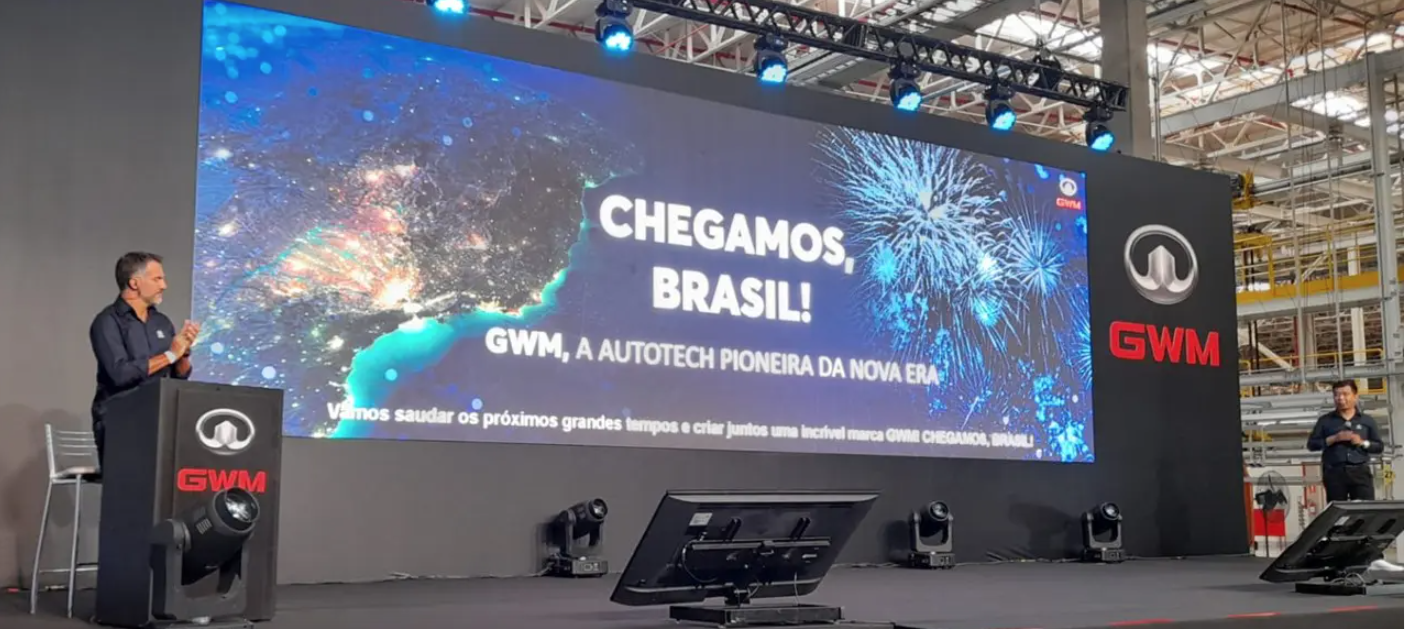

Hiratuka points to Great Wall Motors’ new factory in Iracemápolis, São Paulo (the Chinese automobile manufacturer bought what was then a São Paulo Mercedes Benz factory in 2021). Great Wall Motors is adapting its hybrid vehicles, which will be manufactured in Brazil from 2023, to run on ethanol – the most-used fuel in the country. Ethanol is a byproduct of Brazil’s enormous sugarcane industry and significantly more environmentally friendly than traditional oil-based fuels. There are plans to transform the currently 100 per cent manual factory into one that’s 50 to 60 per cent automated.

Great Wall Motors is also looking to partner with local businesses to develop a way to use ethanol as a source of hydrogen for its hydrogen-fuelled cars, which currently use compressed hydrogen in cylinders. It’s already working with a Brazilian telecommunications operator to develop the vehicles’ interconnectivity system.

Eventually, it will manufacture batteries for its 100 per cent electric vehicles there too.

Another example of Chinese expertise meeting Brazil’s needs is the merger between the State Grid Corporation of China and State Grid Brazil Holding (SGBH), which controls transmission lines connecting the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant in Pará to Brazil’s southeast. The two electricity giants are developing dry air-core reactors that will transmit at a voltage level never before used. This new technology will compensate for losses in SGBH’s long transmission lines, is simpler to maintain, and is better for the environment than the currently used reactors.

On the trade front, Cariello expects that Brazilian exports to China will only go up: “With the growth of the Chinese middle class and the increase in its purchasing power, there are niches that could be explored by Brazilian producers, especially in a sector in which we are already competitive – F&B,” he says. Examples given include premium meat cuts, selected fruits, dairy, specialty coffees, honey, alcoholic beverages and other high-end food products. “Chinese consumers could also explore the fashion sector and the idea of Brazilian exoticism, with an appeal to products from the Amazon rainforest, for example,” Cariello added.

These considerable opportunities in trade and foreign investment signal a promising symbiotic future for Brazil and China.

Brazilian agri-exports to China to expand

- China is Brazil’s largest trading partner, followed by the US.

- In 2021, Brazil exported 34 per cent of its agri-products to China; the country is China’s main supplier of these goods.

- A new trade deal is set to boost agri-imports even higher, opening China up to corn, soybean meal, concentrated soy protein, peanuts, and citrus pulp from Brazil.

- The Brazilian Association of Corn Producers is in talks with China about Chinese approval for certain types of genetically modified maize.