In the short book ‘The Soul of Macao: A Study of Chinese Businessmen and Society in the Late Qing Dynasty’, Lin Guangzhi provides an insight into a group of businessmen who modernised Macao in the Qing dynasty.

In 1894, a group of Macao businessmen opened a silk reeling factory, setting a new milestone for their community. With more than 800 men and women employed there, the factory was the largest industrial plant owned by Chinese in Macao.

It was one of five factories invested by Ho Lin‑vong – the others made firecrackers, firecracker paper, and tea – and part of a much larger shift. Ho was one of a group of Chinese businessmen who rose to prominence in the latter half of the 19th century to lead the city’s industry, commerce, and gambling.

Their work is celebrated in the short book The Soul of Macao: A Study of Chinese Businessmen and Society in the Late Qing Dynasty. Published by the Macao Foundation and Joint Publishing, the book details the modernisation of Macao during the final years of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). By focusing on the Chinese population, author Lin Guangzhi provides insight into the history of an important and often overlooked segment of Macao society.

The book describes how the Portuguese administration encouraged the formation and development of these businesses, so that by the 1860s, the city’s economy was dominated by Chinese family companies.

They used their wealth to set up medical, educational, and welfare institutions for the poor and needy, and to establish associations that served as both a bridge between the colonial government and the city’s Chinese population, and a spokesman for them. They also played a role in mediating business disputes and social conflicts.

Many of these institutions are flourishing today, including the Kiang Wu Hospital, Macau Tung Sin Tong Charitable Society and Macao Chamber of Commerce, fulfilling the same critical roles more than a century after their founding.

Chinese business blossoms

A survey by the Guangdong government in 1809 found that 3,100 residents of Macao, men and women, were engaged in commerce. Nearly all of them operated on a small scale, unable to compete with the larger foreign trade firms held by the Portuguese.

Then, on 20 November 1845, Queen Maria II of Portugal unilaterally declared Macao a free port. This opening of trade coincided with a push for greater colonial control under João Maria Ferreira do Amaral, installed as governor the following year. Amaral levied taxes and rent on the Chinese population, then expelled local customs officials, destroyed the customs houses, and cut off rent payments to the Qing government.

His actions aroused the anger of the Qing government and many Chinese, culminating in his assassination on 22 August 1849. A group of seven men pulled Amaral from his horse and beheaded him; he would be the only governor of Macao to be killed there in more than 400 years of colonial rule.

Despite this violent rebuttal, Amaral’s policies continued under his successors. This included the publication of regulations covering business and commerce, and the issue of licences for different sectors, including gambling, opium, salted fish, beef, port, fireworks, and kerosene. Nearly all were issued to Chinese businessmen.

When Manuel de Castro Sampaio visited the city in 1867, he discovered “the key parts of Macao’s trade” were in the hands of Chinese. Of the 40 large Chinese firms he found, 36 had their headquarters in Macao. Some had branches in the mainland, Singapore, Penang, and Thailand.

These family businesses belonged to people whose ancestors had emigrated from the Pearl River Delta and Fujian province. The patriarchs ran them in the traditional manner, designating their sons as successors and employing members of their extended family to cut costs and ensure loyalty.

As it is today, gambling dominated local industry during the late Qing dynasty. Taxes from gambling accounted for about 50 per cent or more of government revenue most years, peaking at 75 per cent in 1884 and 1885. The government issued licences for specific forms of gambling to companies, with a time‑limit on the successful bid, just as it does today.

Building a name on betting

The family of Ho Lin‑vong was one of those with a gambling licence and a business leader. A native of Shunde, Ho’s father came to Macao in the early 19th century. He obtained licences for fantan, still played in some Macao casinos, and Weixing. In the Weixing lottery, instead of a series of numbers, people drew names of candidates for the imperial civil service exams, winning if their candidate passed. The Ho family also traded opium and salt.

By the time he died in 1888, Ho senior had become a millionaire and one of the most famous names in the gambling sector. He left behind 10 children, including Ho Lin‑vong and his only brother. They took over the family business, and during his tenure, Ho emerged as a pioneer in the development of industry in Macao.

Between 1882 and 1892, he partnered with other investors to open five factories, including the record‑setting silk factory. He turned much of his wealth and time toward philanthropy, helping found two major charitable institutions: Kiang Wu and Tung Sin Tong. He was also active in Chinese politics, supporting revolutionaries such as Dr Sun Yat‑sen and Kang Youwei. In November 1896, he established a newspaper and became its manager.

Gambling dominated local industry during the late Qing dynasty. Taxes from gambling accounted for about 50 per cent or more of government revenue most years.

Ho campaigned against opium, which his family had traded in, and foot‑binding. The family extended an invitation to Alicia Little, a British author and prominent voice against foot‑binding, to visit their home after giving a speech in the city. Little was the leading European campaigner against foot‑binding at the time, having founded the Tien Tsu Hui (Natural Foot Society) in 1898.

Her book describes the warm welcome she received in their large, European‑style home with its luxurious decorations, art works, and billiard table. “But, sadly,” she wrote, “his eldest daughter still had her feet bound.”

Healing those in need

Another wealthy business pioneer was Cao You. A native of Xiangshan (now Zhongshan), he immigrated to Macao as a young man. He invested in the silk factory along with Ho and three others. After eight years of operation, it closed in March 1898; Cao had died two years earlier. His eldest son, Cao Shan‑ye, who had taken over the family business, paid 3,010 yuan to buy the land and equipment of the factory.

Cao You was also one of the four founders of Kiang Wu Hospital, the first in Macao to serve the Chinese population. The four signed an agreement with the colonial government on 28 October 1871 to lease land and build the facility. Cao served as general manager twice, in 1874 and 1887.

The hospital opened less than a year later in June 1872. While the government provided the land, all other costs were covered by a contingency of 71 businessmen and 152 companies. Kiang Wu offered traditional Chinese medicine to poor and needy Chinese who could not afford treatment from private doctors.

In 1892, it hired Sun Yat‑sen as its first western doctor. Cao and his son strongly supported the work of Dr Sun at a time when western medicine, with its knives, needles and anaesthetics, seemed bizarre to most Chinese.

Cao served as one of six witnesses required to allow Sun to lease space for his Chinese/Western pharmacy, and in his will, deposited with the Hong Kong High Court in September 1896, Cao left 144 taels to pay for debts owed by Sun’s pharmacy.

His son, Cao Shan‑ye, went on to hold important posts assigned by the colonial government. One was as a member of a committee to welcome the future tsar, Nicholas II of Russia, in 1891. Nicholas visited the city as part of a more than 51,000‑kilometre journey, from October 1890 to August 1891, designed to prepare the heir apparent for his future duties.

The transcontinental journey took him from Russia to Italy and Greece, then down to Egypt before travelling to India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Thailand, and China. He visited tea plantations and factories in the Nanjing area before moving on to Hong Kong, where he arrived on 4 April 1891. The visit to Macao came before his departure for Japan on 27 April. A failed assassination attempt in Ōtsu, Japan, cut his trip short; Nicholas II was the first, and only, tsar to visit Siberia and the Asia Pacific Region.

Charity and change

Another prominent businessman and philanthropist among the four founders of Kiang Wu was Wang Lu. Born in 1805, Wang’s family were natives of Quanzhou in Fujian province who had come to Macao during the reign of Kangxi (1661–1722). The family primarily made its money from property, restaurants, pawnshops, trading, and the Macao staple, gambling.

Wang used profits from these businesses to build a large house and garden. He also donated generously to charity and Buddhist temples throughout his long life. By the time his family, along with 45 other business people, helped found Tung Sin Tong in December 1892, Wang was well into his eighties.

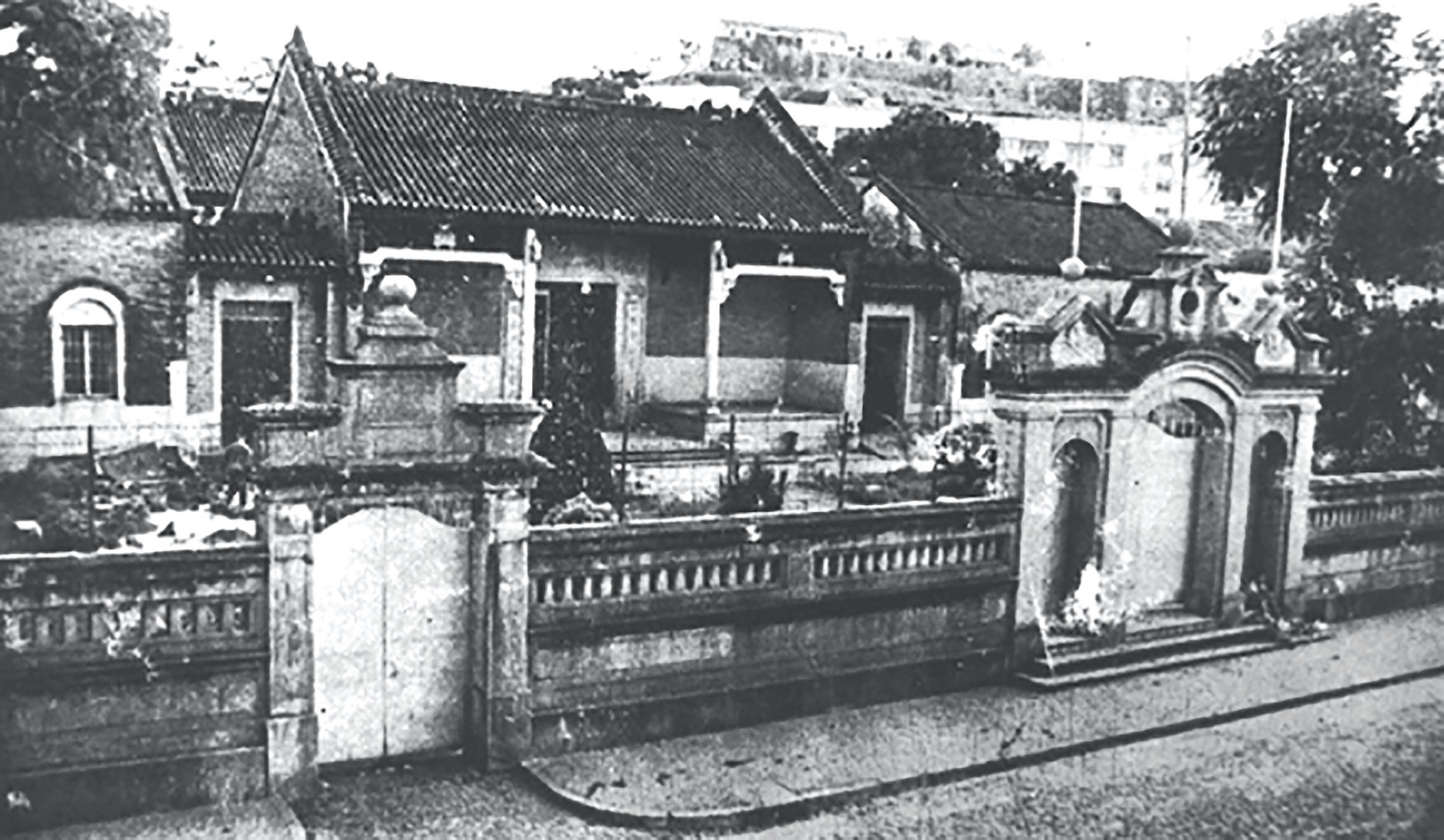

Decades earlier, in 1864, Governor José Rodrigues Coelho do Amaral commissioned Wang to build a large theatre. The Qing Ping Theatre opened its doors in early 1875, the first large‑scale performance venue for Cantonese opera in the city. It hosted an inaugural performance on the same day Wang celebrated his 70th birthday.

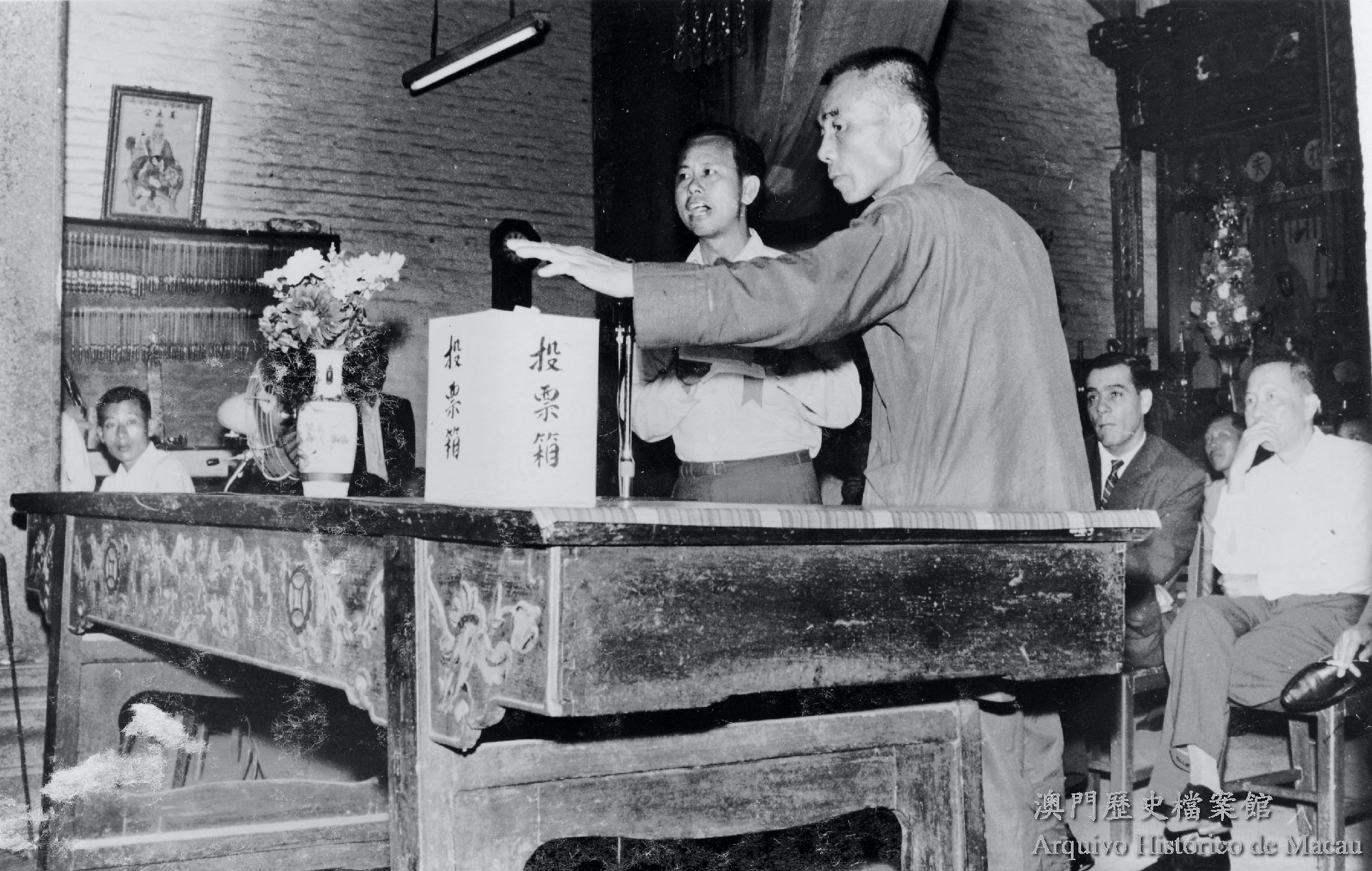

In the years that followed, the theatre presented many operas and eventually films, beginning in 1925. It also played host to important historical events. On 13 July 1909, the revolutionary Tongmenghui held a large meeting there for collective cutting of the pigtail. The Qing government required all male subjects sport the hairstyle, making its removal a popular form of rebellion among revolutionaries of the period.

A large queue formed. The Tongmenghui arranged an orchestra and singing, to create a more celebratory atmosphere, encouraging the audience to take that final step and cut their pigtails. This simple yet powerful protest created a new atmosphere in Macao that echoed throughout Guangdong province, a prelude to the revolution to come.