The Macao Special Administrative Region (MSAR) has undergone enormous development and transformation since its return to Chinese administration in 1999, a little more than two decades ago. Now the MSAR authorities have unveiled an unprecedented plan for the next 20 years, to meet the challenges of projected population growth, economic diversification and greater integration with the rest of China, among others.

The city’s government decided to re-categorise the territory’s urban areas with an ambitious 20-year plan to turn Macao into a “happy, smart, sustainable and resilient city”.

Macao’s government wants to rationalise social resources through urban planning to create a comfortable and peaceful community with improved quality of life.

The Macao Urban Planning Law, which was published in February, establishes urban planning strategies to suit Macao’s characteristics and allow it to take advantage of wider regional and national opportunities.

Macao’s Urban Master Plan (2020-2040) provides for around three square kilometres of reclaimed land from the sea, creating new housing, commercial, tourism, green areas and public spaces.

The plan assumes that by 2040 Macao’s population will have grown from today’s 680,000 inhabitants to 808,000 and its land mass from the present 33 square kilometres to 36.8 square kilometres.

“The master plan project foresees, in the long term, new reclaimed land as spaces for urban development and land reserve, to respond to future population growth and meeting future social and economic demands,” as well as reclaimed land areas along the coast and another site for airport expansion, it reads.

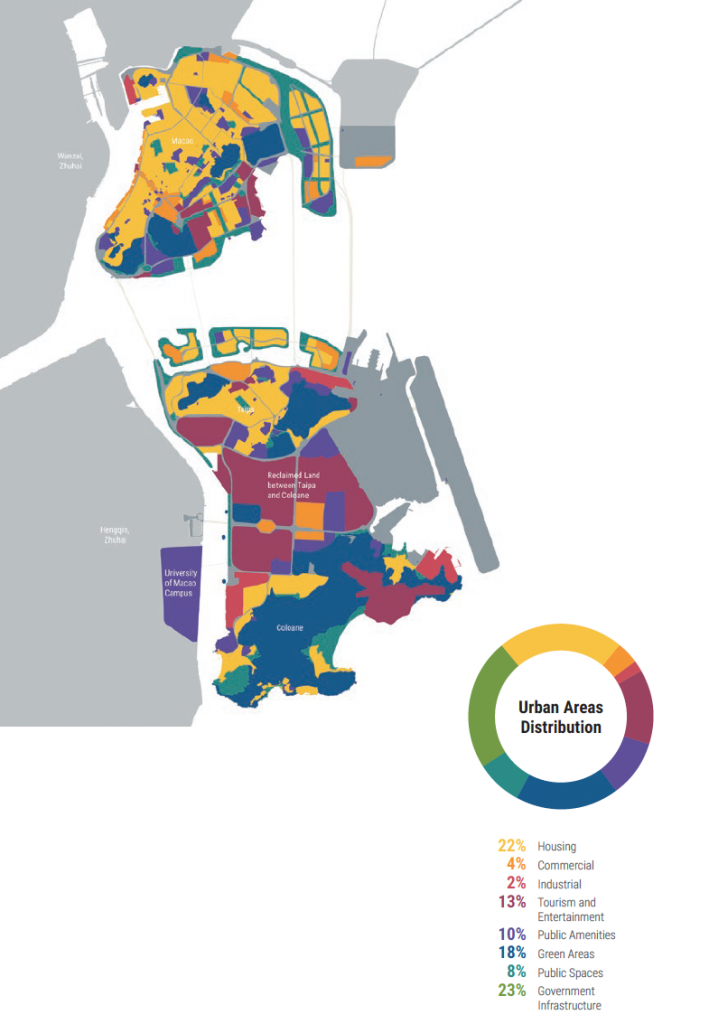

The plan divides the city into 18 “sub-areas for planning”, which are categorised as either urban or non-urban areas. The long-term aim is to turn Macao into a world tourism and leisure centre and into a “beautiful home”. Non-urban areas comprise hills, reservoirs, lakes and wetlands, where any urban development is prohibited. This accounts for 18 per cent of Macao’s total land mass.

From the remaining 82 per cent, 22 per cent is dedicated to housing, 23 per cent to government infrastructure, 13 per cent to tourism and entertainment areas, 4 per cent to commerce, 2 per cent to industry, and the remaining areas to public spaces and green areas and public amenities.

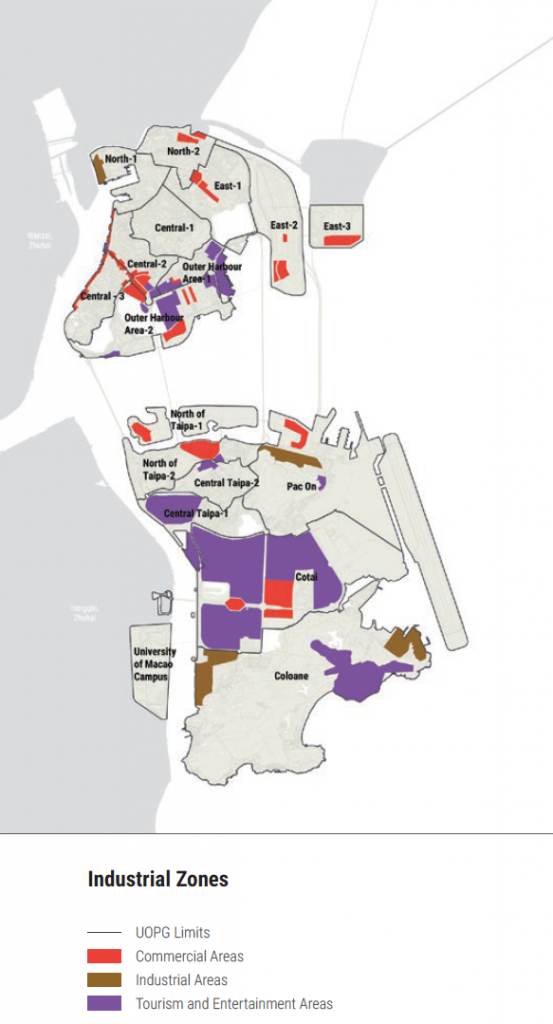

The Urban Master Plan sets out a raft of new commercial areas, such as around the Barrier Gate border checkpoint, the site of the former Lotus Flower checkpoint in Cotai, the original “Ocean World” plot in northern Taipa, and an area south of the Macao checkpoint zone at the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge.

The government also plans to convert the industrial buildings along Avenida de Venceslau de Morais in peninsular Macao into office buildings. Industrial facilities, which are currently scattered across the city, will be concentrated in four existing industrial zones, namely the Zhuhai-Macao Cross-border Industrial Zone in Ilha Verde, the northern section of Pac On in Taipa, as well as Concordia Industrial Park and Ka-Ho in Coloane.

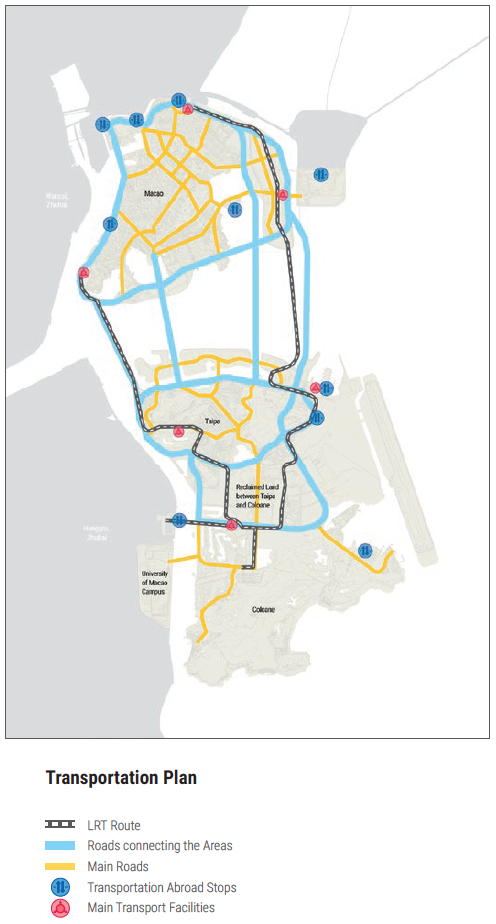

The plan emphasises the Light Rapid Transit (LRT) network that will eventually link the Gongbei border crossing from the mainland to Taipa island through an underwater tunnel, and also from Taipa to the Macao Inner Harbour, as well as from Taipa to Hengqin Island and Seac Pai Van Housing State in Coloane close to the future Islands Healthcare Complex. Aside from the Gongbei tunnel, the latter projects are due to be finished by 2023.

The Urban Master Plan also proposes the revitalisation of the Inner Harbour area with gardens, commercial areas, and maritime ‘blue projects’ to build new tourist attractions and promote the development of the concept of “Cooperation of one river and two banks” which refers to the Pearl River, and the adjacent cities of Zhuhai and Macao.

What the experts think

Christine Choi

President of the Board of Directors of the Architects Association of Macao

Macao has a unique identity with specific urban planning issues. Some districts have undergone rapid development in recent decades, but others have remained static. The implementation of the master plan should drive rapid redevelopment especially in the Macao peninsula.

Many will argue about whether Macao should be divided into 18 districts as the master plan does. However, one benefit that I see with this approach is the ability to plan, implement and execute plans for each district.

The master plan has identified the primary land use for each zone, but flexibility is needed to adapt to future social needs. Utilising our land resources properly is the key.

I think two areas should be considered in the next phase of development.

First, is the consolidation of transport. Without a well refined transit-oriented development model, Macao will always have a transport problem.

Second, we need to set goals and requirements for the architectural development of Macao.

We need to clarify the minimum Green Building Rating for future architectural projects and set a percentage of urban facilities and infrastructure required for different zones to meet community needs. We can only build a better city with clear goals and rules.

José Luís de Sales Marques

President of the Institute of European Studies of Macao

Decades have passed since the first attempt to put together an urban master plan was initiated in the late 1980s, but good intentions were always blocked by the brick walls of private interest groups, unclear policies and political uncertainties.

Taken as a whole, the master plan is a useful instrument that will guarantee the right balance between public and private interest in urban development, with the final goal being the happiness of the people of Macao.

Notwithstanding the advantages, there are questions left unanswered and some issues in the process of the plan that require clarification.

Firstly, the plan incorporates principles and objectives that have already been determined by Macao’s role as a core city in the Greater Bay Area and, in particular, the implementation of the Guangdong-Macao Intensive Cooperation Zone in Hengqin. There is also the impact of Covid-19 and the new regulations on the gaming industry to consider. Should the master plan take into account the model implicit in the amended gaming law as well as land reserved for emergencies, such as those of makeshift hospitals and other public infrastructure required for acute health or similar crises?

The plan sets general guidelines that will have to be realised for each of the specific 18 territorially based operational units. How will these partial plans implement the general guidelines and what kind of urban quality will they promote?

The 18 planning units were designed according to a rationalist approach, but they don’t necessarily follow the organic or historical growth of the city and its former civil parishes division. This principle is perfectly acceptable for the reclaimed areas and new urban communities, but do they fit the old and historic districts?

The plan contains several well-phrased and catchy goals. However, what is their real content, how are they to be reached, and what is the cost-benefit analysis to show their contribution to Macao’s economy in general and economic diversification in particular?

The master plan raises Macao to a new level of modern urbanism, one that will give our citizens a much better quality of life and will assist integration into the Greater Bay Area. However, it is just the beginning of a process that will require increased efforts from the government as well as society in general.

Rui Leão

President of International Council of Portuguese Speaking Architects and President of Docomomo Macau

There are a series of topics in the master plan that charts a path for Macao.

Zoning: The master plan redefines zoning criteria, allowing a huge range of future design options. The first new zoning definition will allow for the integration of collective uses such as sports, culture, education, and health and government agencies. The Commercial Zone defines areas to develop as new centres integrating housing with other uses. This will allow a great reconfiguration of the city.

Transport: The master plan offers no long-term vision for the LRT network, nor a revision of the bus network. Public transport does not seem to be a priority, which is problematic, as the reduction of private cars and motorcycles is overdue. I believe that with some city-wide planning pedestrian areas in the centre could be expanded.

Heritage protection: The master plan, together with the 2013 Heritage Management Plan, recommends development restrictions for heritage areas. This is a great leap forward and will ease the pressure to develop and urbanise every square inch of Macao.

Housing: The new mixed-use definition for Housing Zones, permitting combined office and housing use, will allow more interesting public housing developments.

Human density: Although there are some vague recommendations to reduce population density in the historic areas and northern districts, the master plan doesn’t prioritise this.

Regional integration: Macao will be highly dependent on integration with the Greater Bay Area and the national economy but this will be implemented by the central government and Guangdong province, and so is beyond the scope of the Macao Urban Master Plan.

The master plan addresses other important fields, such as defining ecological reserves, environmental protection and territorial waters, but unfortunately it does not establish any vision for these areas.