China is strengthening its agriculture and agri-food partnerships with Brazil – and the COVID-19 pandemic doesn’t seem to be affecting this close relationship.

For more than a decade, China and Brazil have been strengthening their trading ties. In 2009, China became the South American giant’s largest trading partner, leading some media voices in the country to dub China as Brazil’s most promising business partner in the world – as well as a strategic ally – due to the Asian nation’s rising demand for raw materials and agricultural produce. Since then, China has become the biggest importer of Brazilian products in the world as well as one of the biggest exporters of its own goods and services to the colourful South American nation. And agriculture and agri-food are

at the heart of this ever-growing trade relationship.

Despite this deeply rooted relationship, however, last month Yang Wanming, the Chinese ambassador to Brazil – which boasts South America’s largest economy – said there was still a ‘large margin for growth in trade’ between the two countries, as well as the potential for new bilateral business ventures and tourism and education partnerships. “I see room for growth in partnerships in infrastructure, agribusiness, energy and health,” said Yang during a forum that was organised by Brazil’s Group of Business Leaders (LIDE). The diplomat’s view is well in line with the general confidence among key actors in trade and investment links between the two countries in the food production chain. Momentum is higher in the agribusiness sector – more than in any other. Initially, the COVID-19 pandemic brought fears that trade links could suffer because of a global economic downturn and slowing demand for all sorts of products. Instead, it seems that links have actually been bolstered.

China is the principal destination of Brazilian agricultural exports, representing one-third of the almost US$100 billion (MOP 801 billion) worth of produce that was exported by the South American country last year in this sector, according to ‘China-Brazil Partnership on Agriculture and Food Security’, a new book published in June by the University of São Paulo’s Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ) and the China Agricultural University’s College of Economics and Management. Today, as the book – edited by Sílvia Galvão de Miranda, Marcos Jank and Pei Guo suggests, Brazil is the main supplier of agri-food products to the Asian giant nearly 20 per cent of China’s imports – and ranks number one in the trade of soybeans, beef, poultry, cotton, sugar and cellulose pulp.

Important exports

The Foreign Trade indicator (Icomex) of Brazilian think tank Getulio Vargas Foundation, which analyses the country’s trade every month, confirmed a trend in May that had already been signalled in the previous months. The data showed there had been an increase in Brazilian exports based on commodities for the Asian market, including agricultural and mineral products that are sold on the international market. It also showed a recent slump in some markets, including the US, Mexico and Argentina markets, thus making Brazil’s trade links with China all the more important.

In May, the volume of agricultural and mineral products, as well as other important commodities, exported by Brazil to China grew by 64.7 per cent more than in the same month in 2019. In comparison, Brazil exported fewer products to Asia in general during the same time. Soybeans accounted for a total of 52.8 per cent of all these exports to China, with iron ore and oil accounting for 13.4 and 12.2 per cent respectively. Other exports included beef, pork and chicken, which collectively accounted for about 9.5 per cent of the total. In all, according to Icomex, between January and May, China accounted for 32.5 per cent of all Brazilian exports, mostly agriculture and mineral products, and 20.8 per cent of all the country’s imports, which primarily included manufactured goods, drilling or exploration platforms and electronic components.

According to the Brazilian Association of Animal Protein (ABPA), Brazilian poultry and pork exports to China may break a new record this year, surpassing one million tonnes by the end of the year compared to the 834,000 tonnes that were shipped last year. And even though international trade is slumping in general due to the global economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which primarily deals with trade, investment and development issues across the world, this year Brazil should be able to maintain its levels of exports to the world’s second largest economy. Economist Marco Fugazza, author of April’s UNCTAD study ‘Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Commodities Exports to China’, estimates that a drop in Brazilian exports of crude oil and minerals – caused by a drop in oil prices and consumption – is expected to be offset by increased exports of agricultural products like soybeans.

Not all the news may be good in the short term, however. Due to the global pandemic, some concerns are being voiced. For instance, in June, the Brazilian Embassy in Beijing wrote to the South American country’s private sector after a warning was made by Chinese health officials. They warned that Brazilian meat companies that have detected COVID-19 on their premises should suspend exports and if they don’t, it would risk China barring meat exports from the country to its shores for a period. According to the 17 June letter, quoted in the Brazilian press, local authorities in Brazil are now ‘adopting preventative measures that could affect Brazilian exports of meat products to the Chinese market’. Late last month, four export licences to China were suspended by both countries because of health concerns, according to the Brazilian newspaper ‘Valor Econômico’. More could suffer the same fate in the near future.

Mutual relations

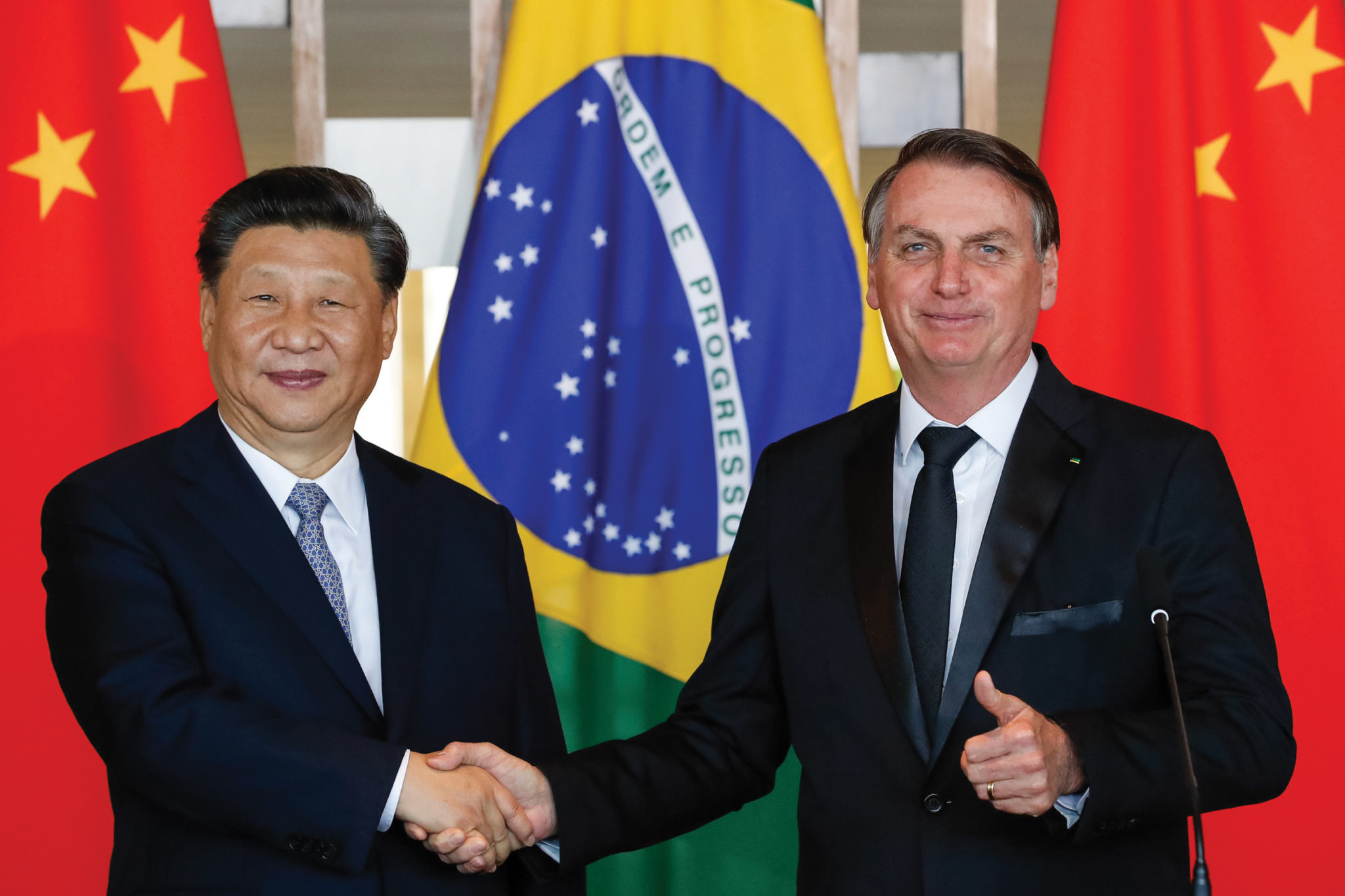

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro visited Beijing in October last year. At the end of his stay, the two countries signed a series of agreements, including one for the export of thermo-processed meat from Brazil to China. Also agreed were regulations for the export of cottonseed meal, which is used for animal feed. China imported US$4 billion (MOP 32 billion) of cottonseed meal last year. During the meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Bolsonaro underlined his country’s interest in strengthening trade relations. “Today,” he said, “we can say that a considerable part of Brazil needs China and China also needs Brazil.” Xi said that China stands ready to ‘import more quality Brazilian products’ and ‘products with high added value’, as well as to expand co-operation in the areas of agriculture, energy, mining, aerospace and infrastructure construction.

With China’s diplomatic relations with the US and Australia – both historically important trading partners in the agricultural sector – strained for multiple reasons including accusations related to the pandemic as well as some rises in trade tariffs, a handful of analysts expect that China’s trade with both nations will suffer this year. But that could be good news for Brazil as it could see its market share substantially increase in the Chinese food market, with products like exported beef. According to CNN Brasil analyst Lourival Sant’Anna, Brazil could replace ‘Australians in the export of commodities, especially meat’ to China as the Asian giant enters ‘what could become a trade war with Australia’.

Brazilian meat exports were favoured by the Chinese and there was a ‘greater opening’ of the Chinese market to the South American country last year, according to André Pessôa, president of Brazilian agribusiness consultancy Agroconsult. In a recent article, Pessôa highlighted ‘the management of the skillful and competent minister [of agriculture in Brazil] Tereza Cristina, who was able to negotiate personally the qualification of many Brazilian slaughterhouses’ to export to China over the past year. According to ‘Valor Econômico’, Tereza Cristina created, at the end of last year, a new special unit to handle relations with China. It’s called ‘Núcleo China’ – literally ‘China Nucleus’ – and its formation underlines the growing importance of Sino-Brazilian trade relations when it comes to the country’s food exports. It’s headed by Larissa Wachholz, the former director of business and investment consultancy Vallya and a master’s degree holder in contemporary China from the Renmin University of China. Wachholz has already established four priority areas of activity for the unit: commercial openings, the attraction of investments, an information centre and both innovation and sustainability.

Investing and growth

It isn’t just imports and exports on the table. China is looking at Brazil’s agri-food sector as a place to invest. It is increasingly ramping up its investments in a bid to become a key grower in the South American giant’s rich fields. China’s Pengxin Group has been leading the charge, through its subsidiary Dakang International. Founded in 1997 by Jiang Zhaobai, Pengxin has grown from a real estate developer to a worldwide buyer of agricultural businesses and it is now expected to become one of the globe’s leading grain trading groups. In 2016, the group paid US$290 million (MOP 2.3 billion) for a 57 per cent stake in Brazilian soybean company Fiagril, based in Mato Grosso state, as well as US$253 million (MOP 2 billion) for 54 per cent of Belagricola, which is one of Brazil’s largest grain trading companies. Dakang vice-president Richard Fan told the Brazilian press recently that in the 2019-2020 harvest the firm plans to export directly – without the use of trading companies – two million tons of soybeans to China, which is four times as many as it exported in the 2018-2019 harvest.

More recently, China’s largest grain, oilseeds and food company COFCO – which stands for China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation – has taken a central role. With Brazil’s agriculture minister in attendance at the 2019 Brazilian Agribusiness Congress in August last year, Johnny Chi, chairman of COFCO International, said ‘the long-term relationship’ between the two countries and each others’ businesses ‘looks very solid’. According to COFCO, over the coming years it plans to increase its investment in new infrastructure, demonstrating the company’s intentions towards Brazil. Most of this investment, according to the firm, will go into logistics and storage. Chi also said that COFCO, in the future, ‘is keen to discuss further investment into Brazilian farms and farmers’, including ‘through financial credit for agriculture inputs’ – which are products permitted for use in organic farming like feedstuffs and fertilisers – ‘and technology’.

COFCO intends to ‘build its partnership with Brazil beyond soybeans’, according to the firm, and it also wants to support Brazil’s transition to more sustainable agriculture. In particular, the group is looking at ways to channel long-term financing to support the expansion of soy production on degraded land. According to COFCO, Brazil has more than 25 million hectares of open land that could be used for soy production. “We hope,” said Chi at the event, “to offer appropriate financial incentives for sustainable production.”

More to come

The new book, ‘China-Brazil Partnership on Agriculture and Food Security’, says that as well as being Brazil’s major food client, China ‘has also become an increasingly important investor within Brazilian agribusiness’. “A large share of the Brazilian supply of agricultural and food products,” it explains, “is ‘married’ to Chinese import demand and both parties are very aware of their mutual dependence’.

According to ESALQ researcher Sílvia Galvão de Miranda, one of the editors of the book, conditions are now ripe for Brazilian food exports to China to maintain their positive momentum in the short and medium terms. Recent boosts to this relationship, Miranda tells Macao Magazine, have come about following the African swine fever crisis that hit China in 2018 and last year, representing a significant threat to the pig production industry as no vaccine or treatment was available for the disease. Also, she cites the instability in the commercial and political relationships between China and other food importers like the US as another reason for the strengthening of Brazilian-Chinese trade relations in this sector.

Miranda says that exports from Brazil to China, while currently ‘strongly concentrated’ on soy and meat products, ‘can and should be diversified’, in the interest of both countries. From the point of view of Brazil’s strategy, she underlines that effort is needed to ‘identify opportunities for exports of higher added value products’ further up in the industry chain. “Brazil can further consolidate its space in the meat market in China,” says the researcher at the University of São Paulo, “in dairy products, fruits and processed food products with higher added value.” She also underlines that public and private sector participation is ‘essential’ to planning and solving logistical bottlenecks, as well as other issues that could ‘constrain trade growth’. In the dairy sector, she points to the increase in consumption of dairy products in China as opening opportunities for companies in her homeland. But, she cautions, firms ‘will need government support in terms of access to the market and health requirements’.

Brazil and China are not just becoming increasingly linked in the way of trade and investment. They are also becoming increasingly linked in the way of knowledge sharing, particularly when it comes to agriculture. For instance, both the University of São Paulo and the China Agricultural University are part of the ‘A5’ alliance – a group of five universities with some of the best rankings in terms of agri-food and agricultural sciences in the world. Within the scope of this alliance, strategic areas of co-operation between the universities are well defined so that they work together on research projects, including in the areas of agroindustrial economics and on issues related to environmental policies. The University of São Paulo and the China Agricultural University do just that. Relevant issues for both countries, such as water resources, the management of agrochemicals and the management of soil and biodiversity are topics ‘where there is potential for synergies’, says Miranda.

Over the coming years, the relationship between China and Brazil has the potential to become much stronger than it is right now – and it is clearly strong right now. Miranda suggests that the growing bonds between both countries in the agri-food sector are expected to grow on ‘a sustained basis’. “Certainly,” she concludes, “as it accounts for more than a quarter of all Brazilian exports, this trade relationship is strategic for the agribusiness sector. In this pandemic period, the relationship has become even more relevant to Brazil’s GDP and trade balance than it ever was before.”

A history of friendship

Close China-Brazil ties have been forged for more than 200 years

- The first Chinese community was established in Brazil In 1812, before the South American country became independent from Portugal, according to Brazilian historian Eduardo Bueno. He claims that a group of more than 200 farmers were brought from Macao at that time to introduce tea plantations in Rio de Janeiro’s Botanical Garden and at Santa Cruz Imperial Farm. They were not successful, however, and Bueno says the projects were disbanded.

- Later in the 19th century, Brazilian envoys to China, Eduardo Callado and Arthur Silveira da Motta, negotiated the establishment of formal relations between the Empire of Brazil and China’s Qing Dynasty. In September 1880, a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation was signed. The Chinese refused, however, to permit Brazilians to hire Chinese people as contract labourers, knowing that non-white labourers were treated ‘as machines or as cheap labour’

- A fresh wave of immigrants from China settled in Brazil’s São Paulo area in 1900. Today, more than 200,000 Brazilians are considered to be of Chinese descent, including members of parliament, military officials and scientists.

- Formal relations ended between the Republic of China and Brazil following the Chinese Civil War from 1945 to 1949. They were re-established in 1974.

- An official visit to China by Brazil’s minister of foreign relations, Ramiro Saraiva Guerreiro, in 1982, paved the way for another, two years later, by President João Baptista Figueiredo. Also in 1984, Chinese foreign minister Wu Xueqian visited Brazil.

- The China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellites programme, still ongoing today, was launched in 1988, leading to several satellite launches between 1999 and 2019.

- The Brazil-China Strategic Partnership was established in 1993 during a visit to Brazil by China’s then first vice premier, Zhou Rongj. In November 1993, the then Chinese President Jiang Zemin made a historic visit to the South American country.

- Brazil officially recognised China as a market economy in 2004. The then Chinese President Hu Jintao said in his address to the Brazilian Congress on 12 November 2004, that ‘both Latin America and China have similar experiences in gaining national liberation, defending national independence and constructing the country’.

- China became Brazil’s largest trading partner in 2009. Bilateral trade massively increased from US$6.7 billion (MOP 53.7 billion) in 2003 to US$36.7 billion (MOP 294 billion) in 2009. In the same year, the then Chinese vice-president Xi Jinping visited Brazil.

- In 2010, the second BRIC – Brazil, Russia, India and China – Summit was held in Brazil, with proposals made for increased co-operation between Brazil and China on political and trade-related issues as well as energy, mining, financial services and agriculture.

- Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Brazil in his current capacity for the first time in 2014, taking part in the sixth BRIC Summit.

- Last year, the two countries celebrated 45 years of diplomatic relations with visits by Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro to China in October and Chinese President Xi Jinping to Brazil during the 11th BRIC Summit in November. Xi vowed to further bolster the ‘extraordinary’ bilateral relationship between the two countries.

- Today, relations are stronger than ever between both countries and trading ties, despite the constraints caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, are booming.