Traditional Chinese settlements pátios serve as valuable heritage enriching Macao’s cultural identity.

Architect Jimmy Wardhana was wandering around the old district near the Ruins of St. Paul’s, when he discovered an inconspicuous Chinese doorway that led into a quiet alleyway no more than three metres wide.

Crossing the threshold into the alley, he found a red shrine of Tudigong (Lord of the Soil and the Ground) with coil incense hanging from the ceiling. He continued to explore further inside, appreciating the Chinese vernacular dwellings with gray brick walls lining either side. Some were vacant, deteriorated while others showed signs of occupancy. The adventure was a short one, though, as he soon found himself arriving at a dead end.

“I am surprised to discover such an enclosed residential space in Macao. The architectural characteristics reminds me so much of the hutongs in Beijing,” said the Chinese‐Indonesian Wardhana, who obtained both a Bachelor and Master of Architecture at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

After a quick internet search, he realised that he had wandered into one of Macao’s unique urban fabrics: pátios (圍, meaning an enclosed area), the Chinese settlements mostly built between late 19th and early 20th century outside the boundaries of the Portuguese city centre, when the city had developed into layers of dense fabric connected by streets and lanes.

Wardhana shared this intriguing discovery with his wife, Christine Choi. Originally from Macao, Choi also attended the University of New South Wales, where she earned both a Bachelor and Master of Architecture, as well as a Master of Commerce. The couple established the architecture firm JWCC Architecture in 2010. They share a passion for blending culture into their design projects, which they view as a way to “restore Macao’s identity.”

To probe possibilities for reviving these forgotten community spaces, they quickly set up a four‐person team within the company to look into Macao’s pátios, gathering information about their history, location pattern, and physical condition.

The project started off without an immediate goal, but a few months later, in July 2017, JWCC Architecture was invited to submit a proposal for the Macao exhibit in the Shenzhen and Hong Kong Bi‐City Biennale of Urbanism/ Architecture (UABB). The exhibition would offer the perfect platform to raise public awareness around this fading heritage by translating their findings into a compelling sensory experience.

Restoring a fading urban identity

The UABB is recognised as the only exhibition in the world that explores the issues of urbanisation and architectural development. The 7th edition of UABB opened at Nantou Old Town in Nanshan district in December 2017. With the theme of “Cities, Grow in Difference,” it sought to embrace diversity at different levels of society and champion inclusion in an effort to create a more robust urban ecosystem.

The Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC), in cooperation with the Architects Association of Macau and the Macao Urban Planning Institute, held a contest to select the Macao representative for the exhibition. The proposal submitted by JWCC Architecture, entitled City Magnified: Re‐discovering of a Diminishing Urban Identity, took the top prize.

“The judging panel chose our proposal because the characteristics of pátios fulfilled the theme of the exhibition, being an urban village that survived through centuries amid modern development and urbanisation,” Wardhana explained.

The concept of sustainability provided the basis for their proposal, comprised of four pillars: social equability, economic prosperity, environmental sustainability, and cultural vitality.

“In some European countries, artists and architects make use of the abandoned spaces to host cultural events and performances, which has drawn a lot of visitors and injected new lives to these spaces,” noted Wardhana. “I think we can do the same thing for Macao’s forgotten pátios, to transform them into retail galleries or exhibition spaces to promote art and culture.”

They also stressed that pátios represent an irreplaceable element of Macao’s cultural identity, serving as a close‐knit community space in the past. Choi emphasised this point: “The most important aspect of a culture is about its people. Pátios represent a healthy neighbourhood in which people knew each other so well they would even leave their doors open. Such connection between people is nowhere to be found in modern apartment buildings.”

From concept to creations

With the subsidy of MOP480,000 (US$59,534) granted by the IC following the announcement of their victory in August, JWCC Architecture had less than four months to prepare the Macao exhibit for UABB, where they would showcase their creative installation alongside more than 200 award‐winning exhibitors from 25 countries.

According to Wardhana, it was a whirlwind preparation process in which everyone in the company, including researchers and designers, were involved on different levels. In just a few months, they spoke with people living near or inside the pátios; interviewed experts of heritage preservations for professional opinions; launched MacauPatio. com for promotion and sharing; and published a small booklet documenting all the work done for the exhibition as a gift for visitors.

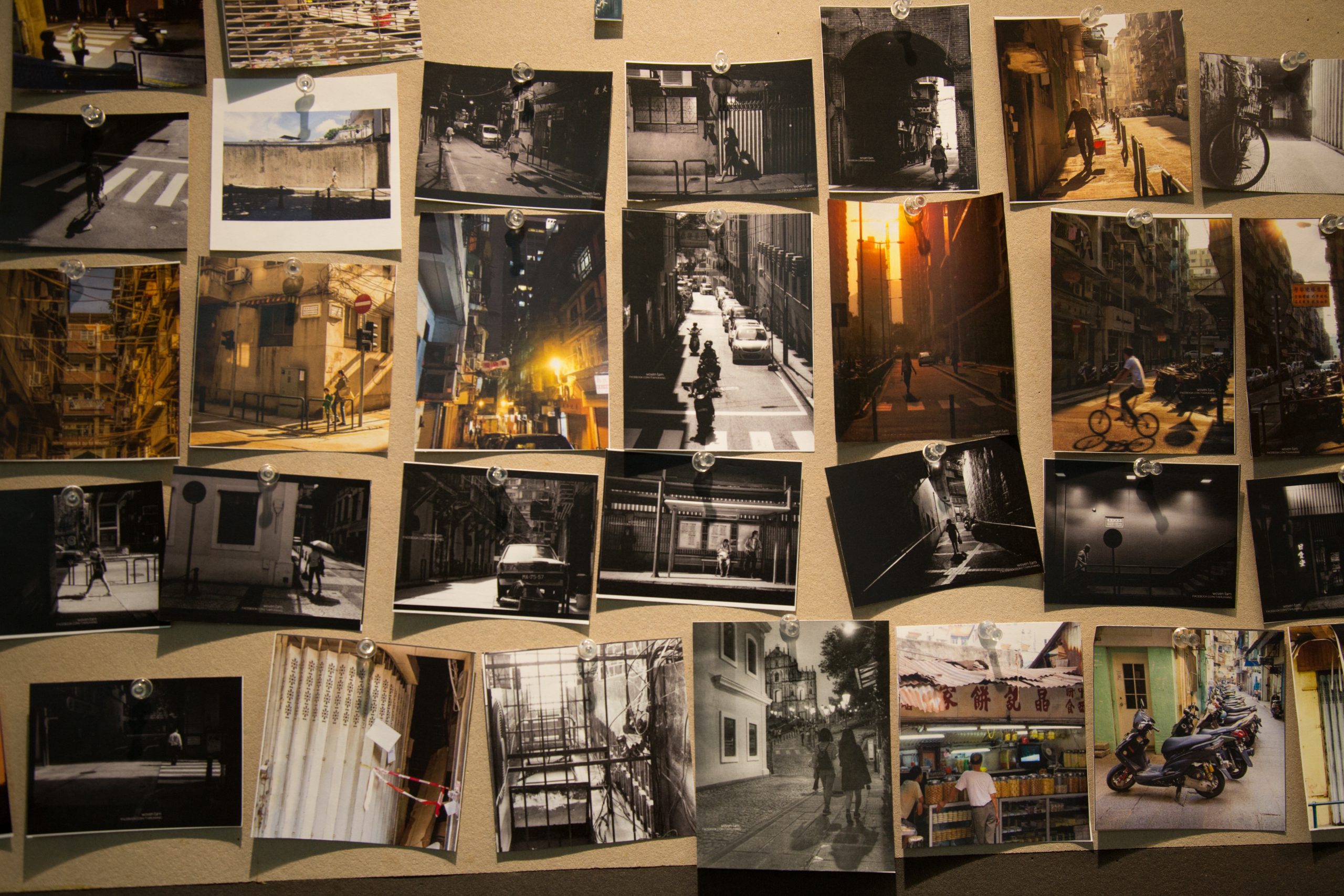

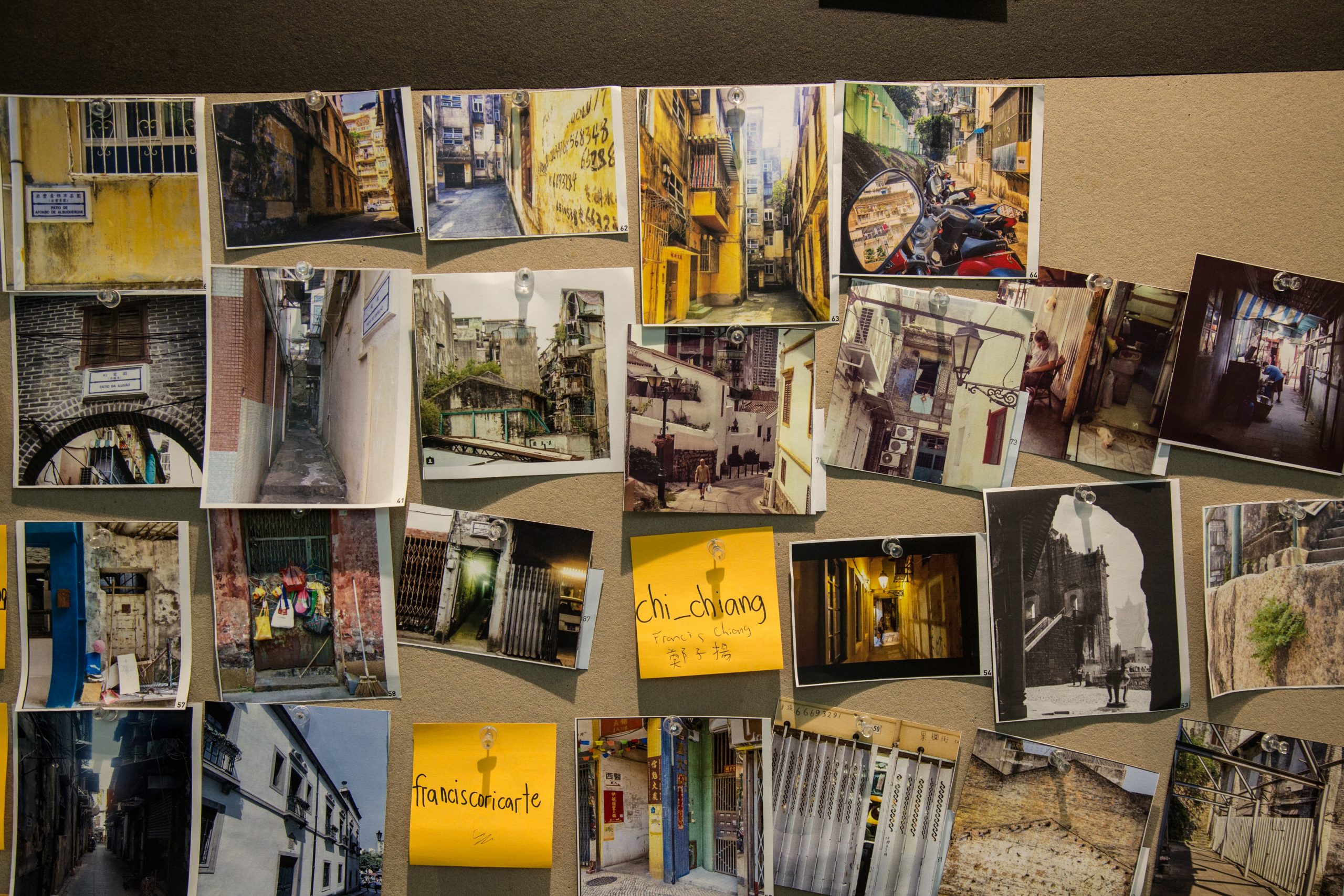

To understand general perceptions on these fading heritage spaces, the team also leveraged social media, encouraging users on Instagram to submit photos of pátios with captions. They received over 100 photos within the first two weeks. “Macao has more than 180 pátios identified on the map, but the photos we received documented only 20 pátios,” Wardhana noted. “This shows that many pátios in Macao still remain unknown to the public.”

For Choi and Wardhana, the most challenging part was finding a way to convey their ideas through creative installations that would leave a lasting impression on audiences. “The scale was so big as we were talking about all pátios in Macao. Even the judges were worrying about us,” smiled Wardhana.

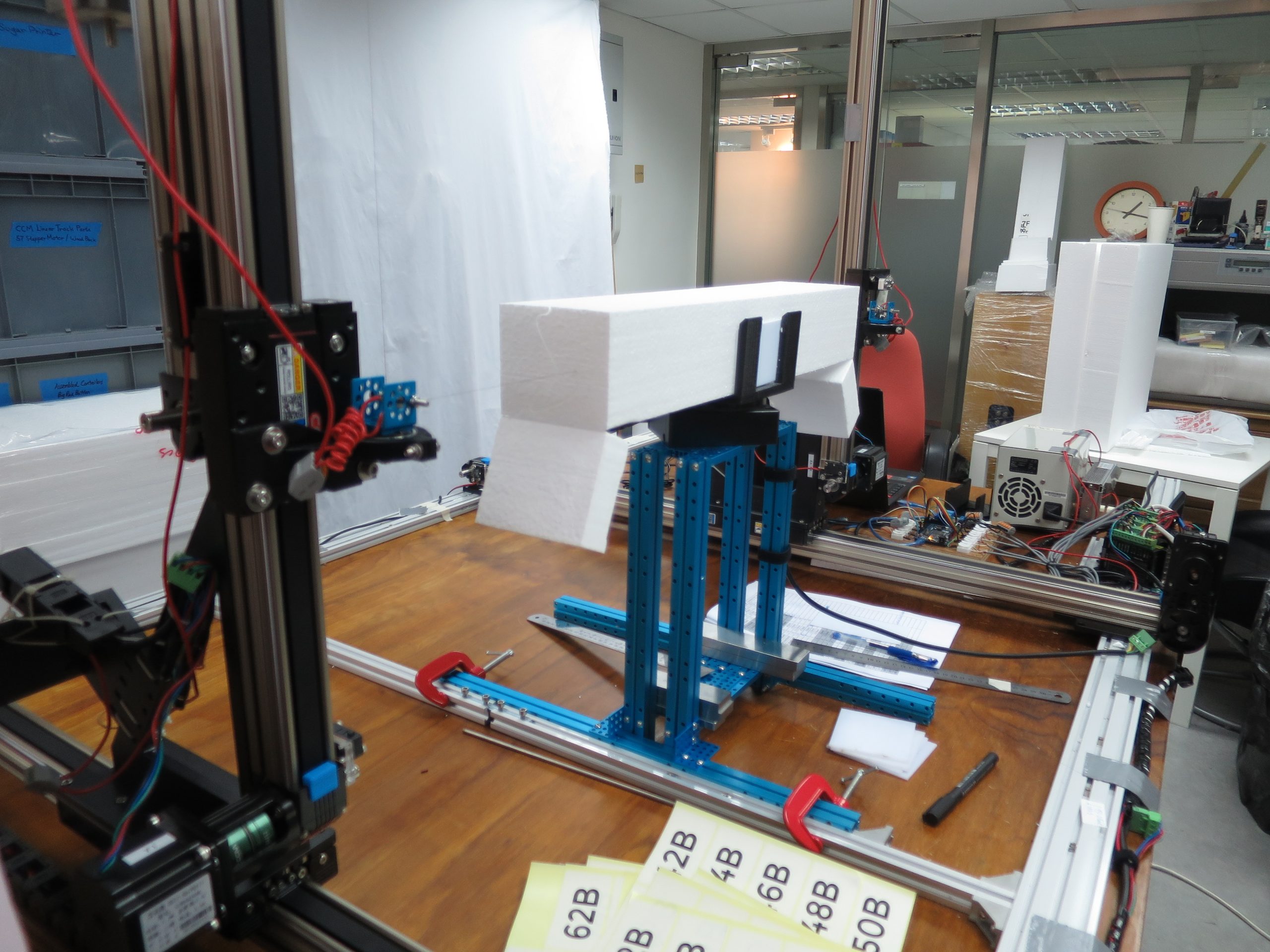

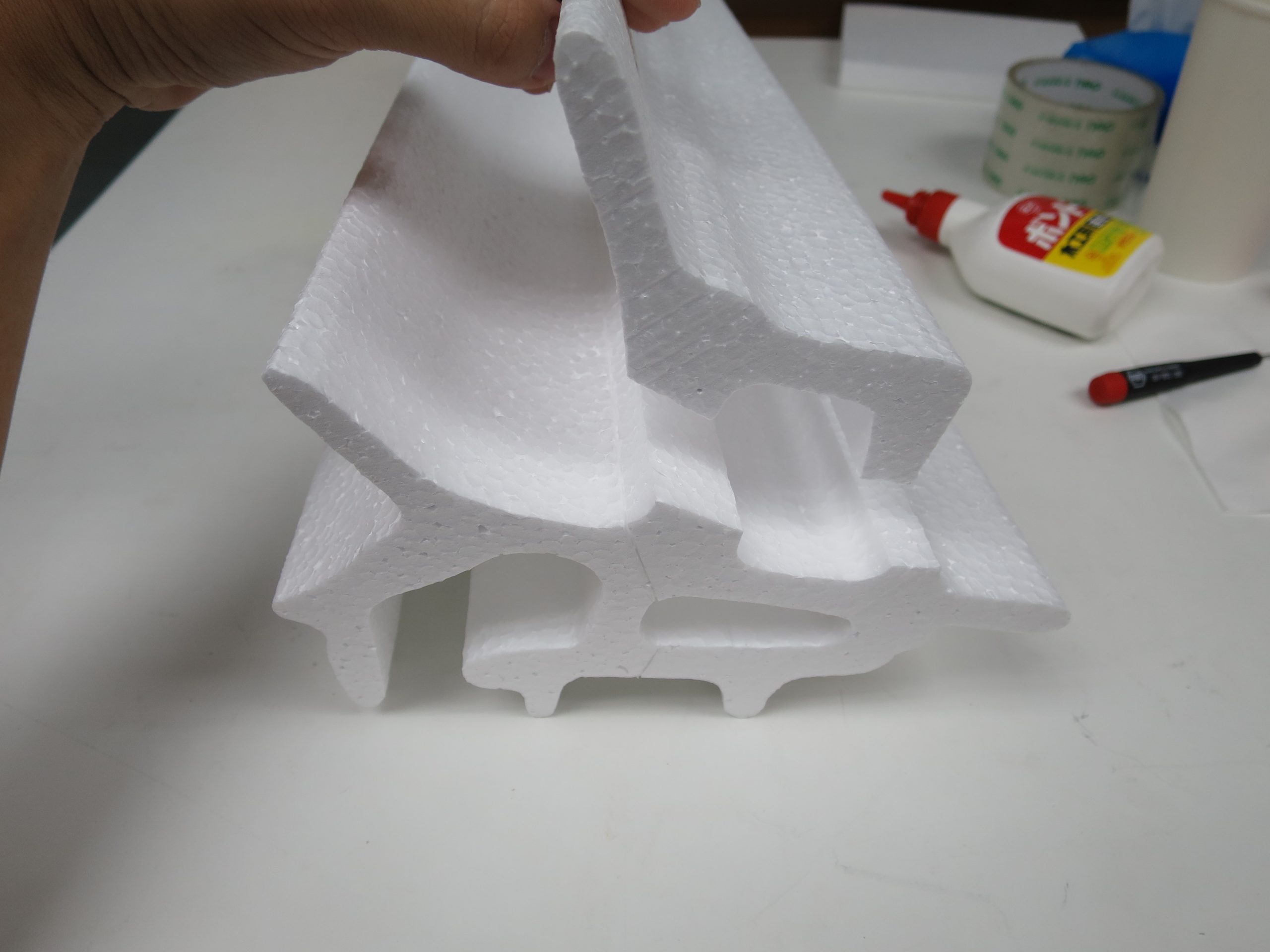

To present the historical urban fabric of Macao to audiences in Shenzhen, the team wanted to create a map of pátios in Macao with polystyrene protrusions, but it required a very delicate cutting device to achieve the perfect shape.

“Just when we were worrying about where to find the machine, we were introduced to Victor Leung,” Wardhana recalled.

Leung, an architect based in Hong Kong, built a large‐format 5‐axis hot wire cutter with adjustable heat settings that was “perfect” for creating the polystyrene forms needed for the display. “We had the entire cutting process completed in Hong Kong, before delivering the products to the exhibition venue.”

The finished product inverts established maps of Macao, as buildings and major roads disappear and the humble pátios extend out toward the viewer.

Each of the stark, white protrusion reflects the shape of a particular pátio, many capped with photographs taken from different spots within the pátio. These pictures are tiny – scaled down to just 1.5 cm wide – far too small to appreciate with the naked eye.

Visitors used magnifiers to view them, encouraging greater engagement and focus while also alluding to how small, and often overlooked, the pátios are in real life.

With the help of a local design company, the team also employed augmented‐reality techniques in the exhibit, which allowed visitors to see the 3D version of the pátios enriched with recreational facilities such as open air cinemas, social club houses and art installations, as they scan the polystyrene protrusions with iPads provided at the exhibition.

“By leading them on a ‘rediscovering’ journey through these special viewing methods,” Choi explained, “the visitors can have a better understanding of the conceptual plans we proposed to revive these pátios.”

The next step

Welcoming thousands of visitors per week, the Macao exhibit has not only provided a new perspective on the city, but it may also have inspired curious visitors to turn their next trip to Macao into an urban heritage adventure.

“Because in their mind, Macao was very small and they only knew the mainstream attractions like the Venetian and the Ruins of St. Paul’s,” Choi explained. “When they found out that there were so many hidden wonders to discover in such a small city, they were really surprised and intrigued.”

Throughout the exhibition period Choi and Wardhana also organised several rounds of guided tours for people with different backgrounds such as architects, design students and participants who submitted pátios’ photos, an arrangement endorsed by the IC in the hope of drawing more people from outside the architectural field to participate in UABB.

They also provided guided tours to students from local highschools in order to foster greater awareness around architecture and its relationship with local culture and history. “We hope to start from the young people. It’s important to enhance their interest when they are in high school already because it’s time for them to choose what to study,” Choi explained.

With the 7th UABB closing on 17 March, the team is now planning to host a second round in Macao, as a continuation of their UBAA exhibit. But not a carbon copy, Choi noted: “We don’t want to just move everything from Shenzhen to Macao. We want to add more artistic and cultural elements to the second exhibition in Macao, to offer a deeper perspective to visitors.”

A challenge worth taking

Amid the fascinating churches, busy largos and plazas, the pátios hidden within the meandering streets and alleys of the historic districts are easy to overlook, even for Macao locals.

According to Regenerating Pátio – Study of Macao’s Historical Urban Fabric published by IC in 2010.

When they found out that there were so many hidden wonders to discover in such a small city, they were really surprised and intrigued

Macao’s pátios were mostly built outside the Portuguese city centre, particularly to the west facing the Inner Harbour. Design of the dwellings inside was based on traditional Chinese techniques involving “two parallel masonry load‐bearing walls on the long side of the house, pitch roof of timber purlin with ceramic tile, and windows or door openings on the building facade facing the pátio.” A small shrine for Tudigong is still a basic component for pátios, with residents sharing the responsibility for daily maintenance and worshipping, making pátios an important platform for strengthening community ties.

While most of the pátios are more than a century old, many have been at least partially rebuilt in the last 50 years. Today, only around 20 pátios in Macao still retain historical significance, and less than 200 historical buildings survive in the pátios.

The Pátio da Eterna Felicidade, located a few blocks away from the Ruins of St. Paul’s, is one of the best‐preserved pátios of Macao, complete with intact Chinese dwellings that incorporate characteristics of wealthy households such as arches and courtyards. Pátio das Seis Casas, located near the Mandarin’s House, takes its name from the six traditional dwellings that surround it, some of which are still occupied by elderly people. Former residents include renowned Russian painter George Smirnoff who lived there during the Second Sino‐Japanese War.

Despite challenges in navigating issues around property rights in pátios and protecting the living spaces of the remaining residents, proactive efforts have been made by the IC to preserve these fading heritage spaces: plans have been formulated to transform pátios with historic value into cultural and creative zones, and restrictions imposed on their reconstruction, such as maintaining its height and facade.

With skyscrapers rapidly changing the urban landscape, residents and tourists will long for these quiet, original spaces that offera moment of tranquillity, and an important opportunity to learn about the history and the identity of the city. The pátios have huge potential to become a significant part of Macao’s historic centre, and may one day inspire locals and tourists to step off the beaten path for an adventure of discovery.