Stepping into the Holy House of Mercy’s Salão Nobre is rather like stepping into a church. Subliminal hymnal music plays softly, complemented by the rich smell of polished wood. Instead of saints, however, these walls are lined with portraits of ordinary mortals (albeit some very admirable ones). They are the benefactors whose generosity has enabled the venerable institution to carry out good works over the past 455 years.

The man who established Santa Casa Misericordia Macau (SCMM) – the Holy House of Mercy’s Portuguese name – maintains a physical presence in the Noble Hall, too. Bishop Belchior Carneiro’s skull sits on a table, as though he’s keeping an eye on his legacy. Carneiro was Portuguese, but many of the faces on the walls are Asiatic. They’re the only indication we are in Macao, not 19th-century Europe.

One of them is an elegantly dressed Chinese woman named Marta da Silva Van Mierop; the imposing scale of her full-length painting is testament to her profound impact on the Holy House’s coffers. Born in 1766, Marta could be the poster child for how the organisation operates. Abandoned by her parents as a baby, she grew up within the Holy House of Mercy. The charity named, fed and clothed her, preparing young Marta for a future in respectable society (which in those days for women, entailed making a successful marriage). Marta wed an Englishman, who bequeathed his large fortune to her in his will. She is understood to have become the wealthiest woman in Macao.

Yet she never forgot her roots. Marta used her money to fund girls’ education initiatives and equip them with dowries. When she died in 1828, she left the bulk of her remaining fortune to the Holy House of Mercy. The philanthropist was undoubtedly aware of the vital role an organisation dedicated to uplifting the marginalised – regardless of race, religion or gender – could play in the world.

Jesus Hominum Saviour

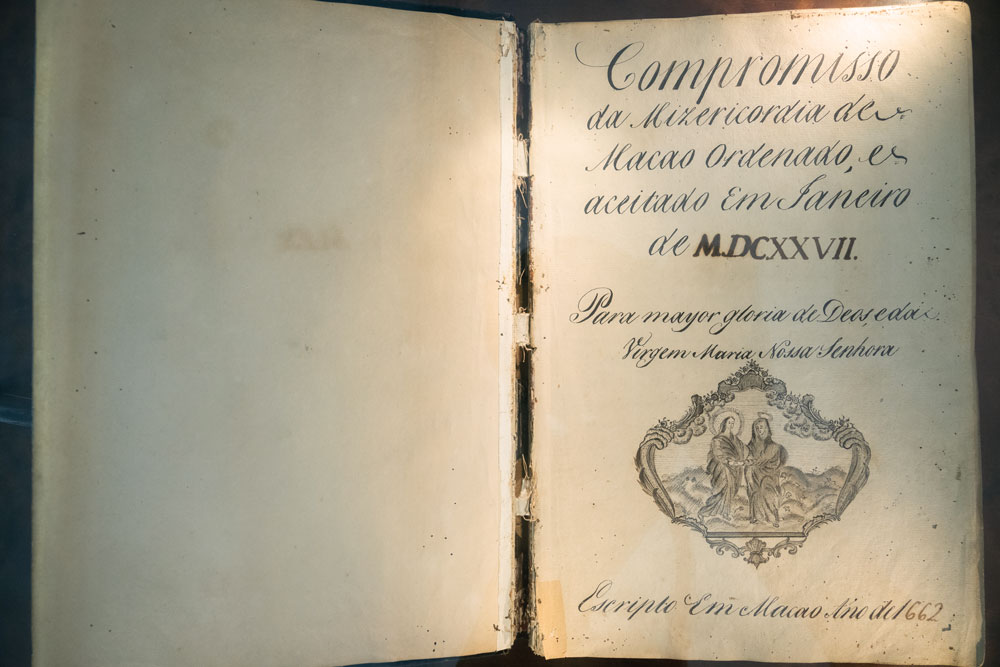

A door near Marta’s painting leads from the Salão Nobre into a charming museum. Most of its 200-odd Catholic artefacts hail from the 18th and 19th centuries. There are delicate cloisonné containers for holy water (cloisonné is a form of enamel work) and ivory figurines of Jesus’ mother, Mary, among religious relics galore. The oldest exhibit is the Holy House of Mercy’s original charter, handwritten in 1662. Much of the room is dedicated to an extensive collection of Chinese porcelain, adorned with a ‘JHS’ monogram encircled by a sun. It’s an emblem belonging to the Jesuits, a Catholic order instrumental in spreading Christianity across Asia (Bishop Carneiro was a Jesuit). JHS stands for the Latin words Jesus Hominum Saviour (Jesus, Humanity’s Saviour).

The collection belongs to the Holy House of Mercy’s long-serving president, José de Freitas, who started collecting it four decades ago. “Wherever I travelled to Europe, around Asia, I’d bring some of it back to Macao,” the 71-year-old tells Macao magazine. It holds deep meaning for Freitas. Made in China, for a European religious order, “each piece reveals a unique and symbolic artistic-religious blend of the multicultural legacy of Macao,” he says. Freitas eagerly points to certain items with the Jesuit monogram reversed; it reads ‘SHJ’. He believes the error resulted from a muddle at the Chinese porcelain factory, as those in charge of painting would not have understood what the Latin characters stood for. But the imperfection just makes those plates, bowls, vases and urns even more precious in his eyes.

The Salão Nobre and the museum are both open to the public and part of SCMM’s white-painted headquarters. This, incidentally, is the only Holy House of Mercy left standing in Asia, though thousands still operate in Brazil and Europe. Freitas says Macao’s regional longevity comes down to due to the territory’s comparatively calm socio-political environment. There was never dramatic backlash against Christians or the Portuguese here, as there was in the likes of India and Japan.

A queen’s revolution

The Holy House of Mercy was the brainchild of Portugal’s Queen Dona Leonor, born Eleanor of Viseu in 1458. She founded the original Santa Casa Misericordia in 1498, in Lisbon, as a means of redistributing the empire’s rapidly accumulating wealth to those who most needed it.

Almost immediately, the concept began accompanying Portuguese explorers on their voyages around the world. There was a Holy House in Ceuta, Morocco, by 1502. Another popped up in Cochin, then part of Portuguese India, as early as 1505. Macao’s was established by Bishop Carneiro in 1569, just 12 years after official Portuguese settlement of the territory.

“In the beginning, the Misericordia was quite an impressive religious and sociological revolution,” says the Macao-based historian Ivo Carneiro de Sousa, who has studied the Holy House of Mercy extensively. “The queen’s goal was to mobilise profits accumulated by the trade bourgeoisie and turn them into works of mercy.” In those days, Portuguese merchants were growing rich quickly, thanks to the empire’s proliferation of maritime trade routes.

These opened access to Asia, Africa and the Americas, treasure troves brimming with silver, spices, and silk, all highly prized by Europeans. But peasants did not benefit from all that lucrative trade, and social welfare had not been invented. The poor, sick, imprisoned and marginalised had to fend for themselves. Small-scale Christian charities did exist, but their religiosity often got in the way, explains Sousa. Queen Leonor insisted that the Holy House of Mercy – while deeply Catholic in character – would be run by laypeople, free from ecclesiastical whims, and help anyone who needed it.

She also made sure the institution was financially independent from both church and crown. The queen’s own substantial wealth helped endow the Holy House with land and properties from the start, enabling it to earn its own money. Then, the idea was for successful businesspeople to bolster its coffers and property portfolio through donations and bequeathments in wills. This was a novel funding model at the time. It worked, however, as Portugal’s merchants were eager to support their very popular queen’s cause. She managed to convince them – good Catholics – that donating to the Holy House was the ideal way to obtain spiritual merit. Hefty donations also promised social prestige and networking opportunities, especially as the fraternity running it grew in power.

Before long, the Holy House of Mercy had become one of two pillars managing Portugal’s overseas dominions. Town Halls were the administrative centres, in charge of enforcing the law, collecting taxes and maintaining public infrastructure. Holy Houses of Mercy ran hospitals, orphanages and other welfare services. Interestingly, they also formed an early international banking system for Portuguese traders, Sousa says. The interest charged on loans also helped fund their humanitarian efforts.

The Holy House in Macao

Macao, while never a Portuguese colony, was in possession of these two pillars almost from the beginning of Portugal’s administration. The Town Hall (known locally as Leal Senado) and the Holy House of Mercy have sat parallel to each other in Senado Square for nigh on half a millenia. Today, appropriately, the territory’s Municipal Affairs Bureau occupies Leal Senado.

Back in 1560s Portugal, however, the bishop who established Macao’s Holy House of Mercy did not imagine himself living and dying in the newly established outpost in Asia. Carneiro felt called to serve in Ethiopia, though had been appointed bishop of the Nicaea region in today’s Turkey. Nevertheless, Pope Pius V made him the apostolic administrator for Portugal’s missions in Japan and China in 1566 – a role he initially performed from India before arriving in Macao in 1568. While Macao became its own diocese in 1576, Carneiro was never appointed its bishop. He did achieve his dream of becoming Patriarch of Ethiopia in 1577, but only ever performed that role from afar. Carneiro didn’t manage to visit the East African country before he died, in Macao, in 1583.

Carneiro’s remains were eventually transferred to St Paul’s Cathedral (now the Ruins of St Paul’s), which was built in the early 1600s. In 1835, some of the bishop’s bones and a cross he was buried with were rescued from a devastating fire that engulfed the building. That’s how his skull came to be sitting in the Holy House of Mercy’s Noble Hall today.

Supporting the blind, elderly and very young

For most of its long history, Macao’s Holy House focused on supporting orphans and sailors’ widows (all too common in a city of seafarers). As neither of those populations has existed in great numbers for some time now, it has pivoted towards providing for the blind, elderly and very young.

The Holy House began aiding blind people in Macao as early as 1900, through subsidising an order of nuns to provide shelter for them. It established its dedicated Rehabilitation Centre for the Blind in the 1960s and, since then, has been working with the visually impaired to build their resilience and help them find places within society.

Vocational training has always been a big part of that. In the past, the centre taught skills such as weaving and wickerwork. Nowadays, there’s more emphasis on computer literacy and learning Braille. The centre is also a place for the visually impaired and their families to socialise, where singing and music can frequently be heard.

The Holy House is also a proud pioneer in elderly care, its president – Freitas – says. Its current facility, the Our Lady of Mercy Home for the Elderly, opened in 2000 and occupies in one of the organisation’s oldest properties: a stately ochre structure near the Ruins of St Paul’s. The home has 128 beds for residents whose advanced age means they can no longer take care of themselves. Freitas notes that Macao’s ageing population makes multi-disciplinary elderly care services increasingly important in the city. He says the Holy House believes that a longer life expectancy “must be accompanied by quality of life”, and that his staff are dedicated to ensuring its patients maintain all the dignity possible.

The organisation runs two day nurseries, too. Creche SCMM in NAPE and Creche Lara Reis, housed within a historic villa overlooking Sai Van Lake. Together, they have the capacity to look after more than 320 children under the age 3. Creche SCMM opened in 2002, in a building supplied by Macao’s government. The other nursery opened in 2022 and is named for a professor – Fernando de Lara Reis – who bequeathed his villa to the Holy House back in 1949.

A provedor’s revolution

Macao’s oldest social solidarity institution underwent an overhaul around the time Macao became a Special Administrative Region of China. It had been in dire financial straits in the final years of the Portuguese administration, according to Freitas – who joined the fraternity steering the Holy House back in 1997. “Some thought that SCMM should end all its services at that time, turn off the lights and close its doors permanently,” he says. “This building would then become one of the many lifeless buildings that were once part of Macao’s history.”

But Freitas and his posse of “vigorous and determined young Catholics” refused to give up. “We felt obliged to continue its mission, whatever the cost, to preserve its history,” he says. “[That sentiment] has a lot to do with our Macanese and Portuguese commitment to remaining in Macao.”

This is when Freitas became the Holy House of Mercy’s president. Leaning on his professional experience in business and real estate, he turned the charity’s financial situation around. Freitas opened what had long been a rather insular institution up to working with other players in Macao’s network of non-government organisations – those united by their will to do good – and forged closer ties with the new government. His efforts paid off.

Looking back, Freitas is immensely proud of what his team has achieved. He personally considers his own work (which is unpaid) for the Holy House of Mercy as his life’s mission. “After almost 25 years as the president – or, as we say in Portuguese, provedor – I practically have the words ‘Holy House of Mercy’ engraved on my forehead,” Freitas says. “Everyone knows me as the provedor of this institution; even people who are my close friends greet me by calling me ‘provedor’ when they see me.”

Today, he declares, there’s no reason Macao’s Holy House of Mercy can’t continue supporting Macao’s most vulnerable for the next 455 years. And the charity’s purpose remains exactly the same as Queen Leonor intended, back in 1458: to perform acts of mercy for those who need it most, whomever they may be.