Photo by António Sanmarful

The incense, matches and firecrackers industries dominated the post-WWII economy of Macao until they were driven away by land shortages and high labour costs.

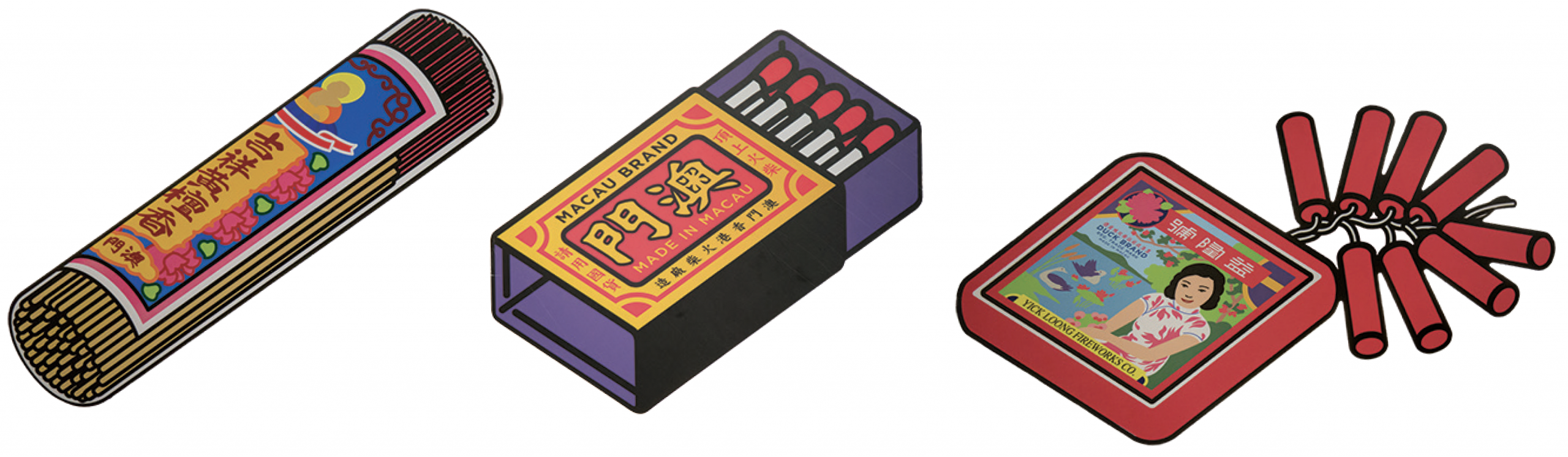

Three industries came to dominate the post‑WWII economy of Macao: incense, matches, and firecrackers. Companies sold locally, and exported to Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and the many overseas Chinese scattered across Europe and North America.

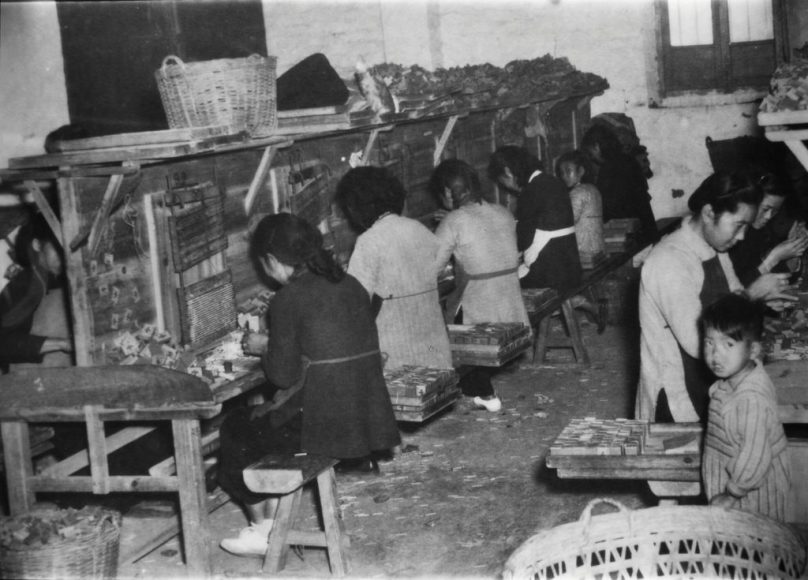

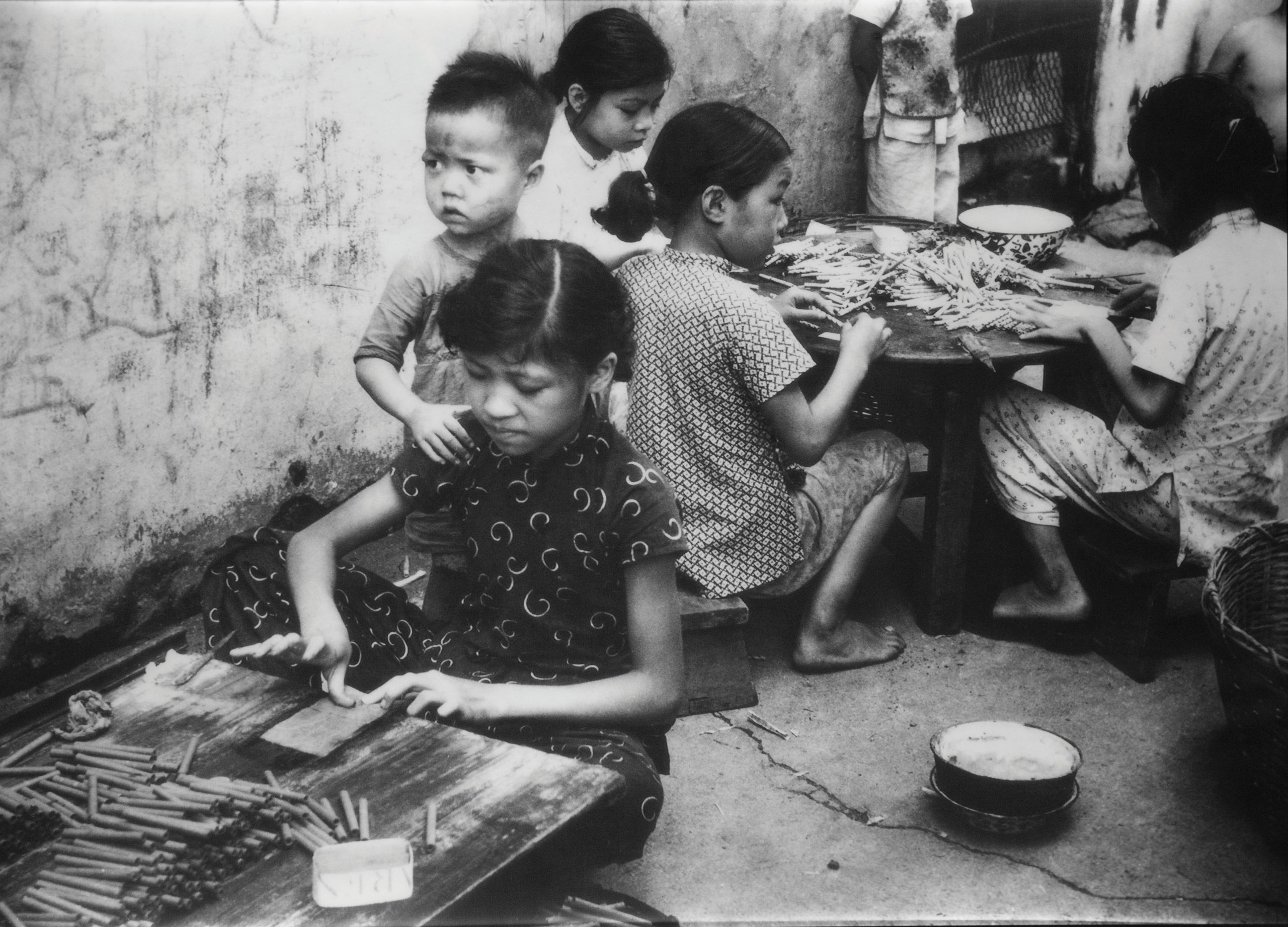

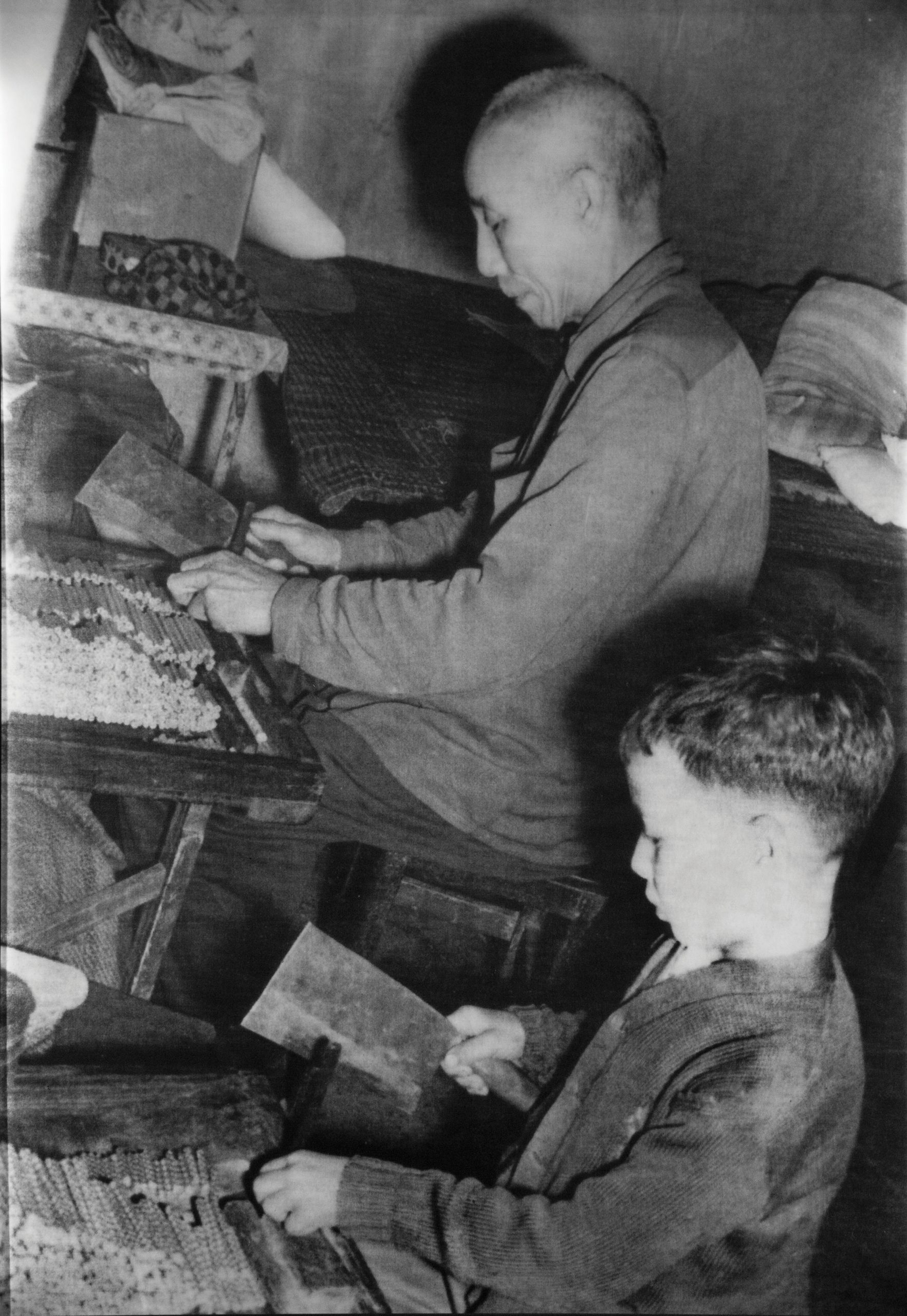

Thousands of people worked in these industries, some on the factory floor while others worked at home and on the streets, where children and old people completed parts of the production process.

Take a walk around the city today, and you won’t find any bustling factories, just finished products sold in mom‑and‑pop stores and supermarkets. Like other once-prominent industries, the production of incense, matches, and firecrackers has moved to the mainland, driven away by land shortages and high labour costs.

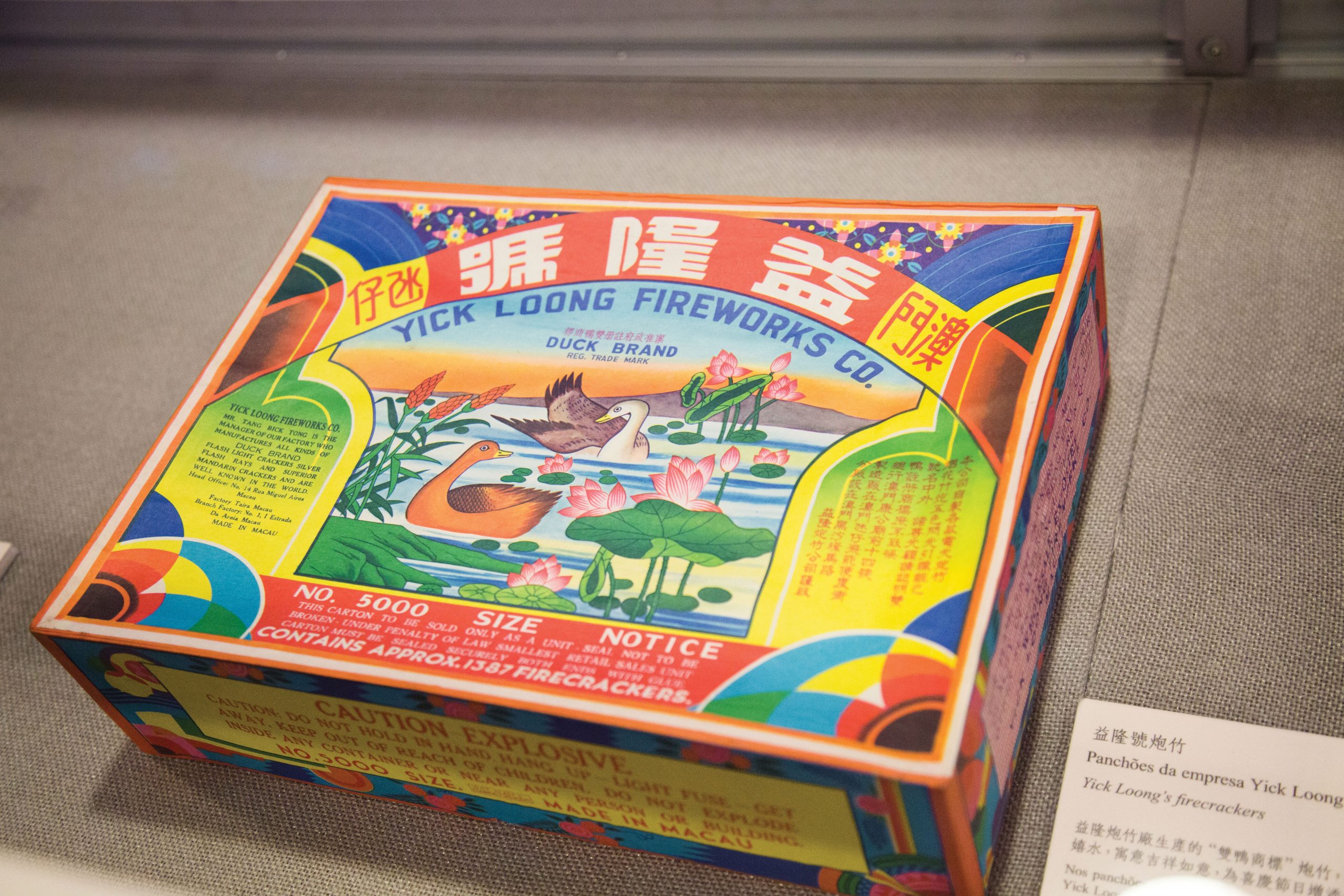

The Macao Museum explores this important period in The Memorable Time – The Traditional Handicraft Industries of Macao, an exhibition detailing the economic and social impact of these industries, particularly in the post‑war period. The exhibition combines guided tours and a number of activities with a curated selection of 210 pieces or sets, divided into six zones: one for each of the three industries, foreign trade, education and factory simulation, and a projection room. For many, the exhibit offers a vivid look into their own family history, parents and grandparents who toiled in these industries once central to Macao’s economy.

The exhibition runs from 28 October 2017 to 25 February 2018. Four guided tours with curators are available this year: 6 and 10 January, and 10 and 24 February.

“We know that this is an important part of our history,” said Gabriel U, a museum staff member who helped put the exhibition together. “It took six months to prepare. Former employees came to the museum for the opening. They were very excited to participate and feel part of the exhibition.”

Traditional products become industrial base

After the British established Hong Kong in 1842, Macao lost its place as the major trade hub linking China to the outside world. It took the city decades to establish new industries to replace the lost trading, industries built on three traditional handicrafts already central to life in Macao: incense, firecrackers, and matches.

The incense and firecracker industries emerged first; records indicate both existed on a smaller scale prior the 1860s. “They started in Macao initially to meet demand from local residents,” said U. “These products were an important part of daily life – in temples, traditional festivals, and for use at home.”

Incense and firecrackers have been part of Chinese culture for millennia. Incense became part of Chinese religious practices at around 2000BC, and continues to be used as an offering or invocation in Chinese ancestor worship, Daoism, and Buddhism.

Firecrackers, invented by the Chinese around 200BC, had their own role in traditional life: the loud noise was believed to drive away devils and evil spirits, and lent excitement and a sense of occasion to Chinese New Year, weddings, birthdays, and other major events. The ubiquity of incense and firecrackers in local culture gave rise to a production base in Macao long before the more industrialised, factory model came along in the 19th century.

Matches arrived in Macao much later. While the earliest record of matches dates back to 577AD in China, the modern, self‑igniting match was not invented until 1805. Macao’s first match factory opened in 1923, and by 1929, the three industries contributed a combined MOP2.9 million to the city’s GDP, 40 per cent of total industrial output.

Production grew steadily over the next three decades, reaching MOP14.4 million in 1962. At that point, there were five match factories, nine firecracker factories, and at least 30 incense shops in the city, with 90 more retail outlets selling incense and paper goods.

Visitors to the city would see women and children, on the streets or at home, making their own contribution to the industries: braiding strings of firecrackers, rolling incense, and sticking labels on matchboxes.

Fragrant industry in Inner Harbour

Most of the raw materials used to make incense had to be imported: spices, incense powder, binder, cove, coloured powder, wrapping paper and, for some brands, sandalwood. Producers employed one of three production methods: paste rolling, powder coating or compression, the most efficient option. Factories sold their finished products to individual families, fishermen, abstinence halls, and temples.

Traditional festivals – Chinese New Year, Ching Ming, Chung Yeung, and the Mid‑Autumn Festival – prompted the biggest sales, both locally and in exports to Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and cities around the world with overseas Chinese populations.

Among the most famous incense producers was Leong Wing Heong. Founder Liang Shou‑tian, a native of Heling village in Xinhui, Guangdong, had his headquarters on Rua de Cinco de Outubro, with a factory and a branch office. He had additional branches in Guangzhou and Hong Kong, and exported much of his production.

Most of the incense factories were located in the Inner Harbour district, especially the San Kio area, Rua de Entre‑Campos, and Rua da Alegria do Patane. The district combined a sizeable population of available workers with the large land area needed to dry the incense, making it an ideal location for the industry.

That all changed in the 1970s and 1980s, as rapid real estate development pushed industry out, turning the drying areas into construction sites for a growing Macao. The industry never recovered.

Prosperity at a price

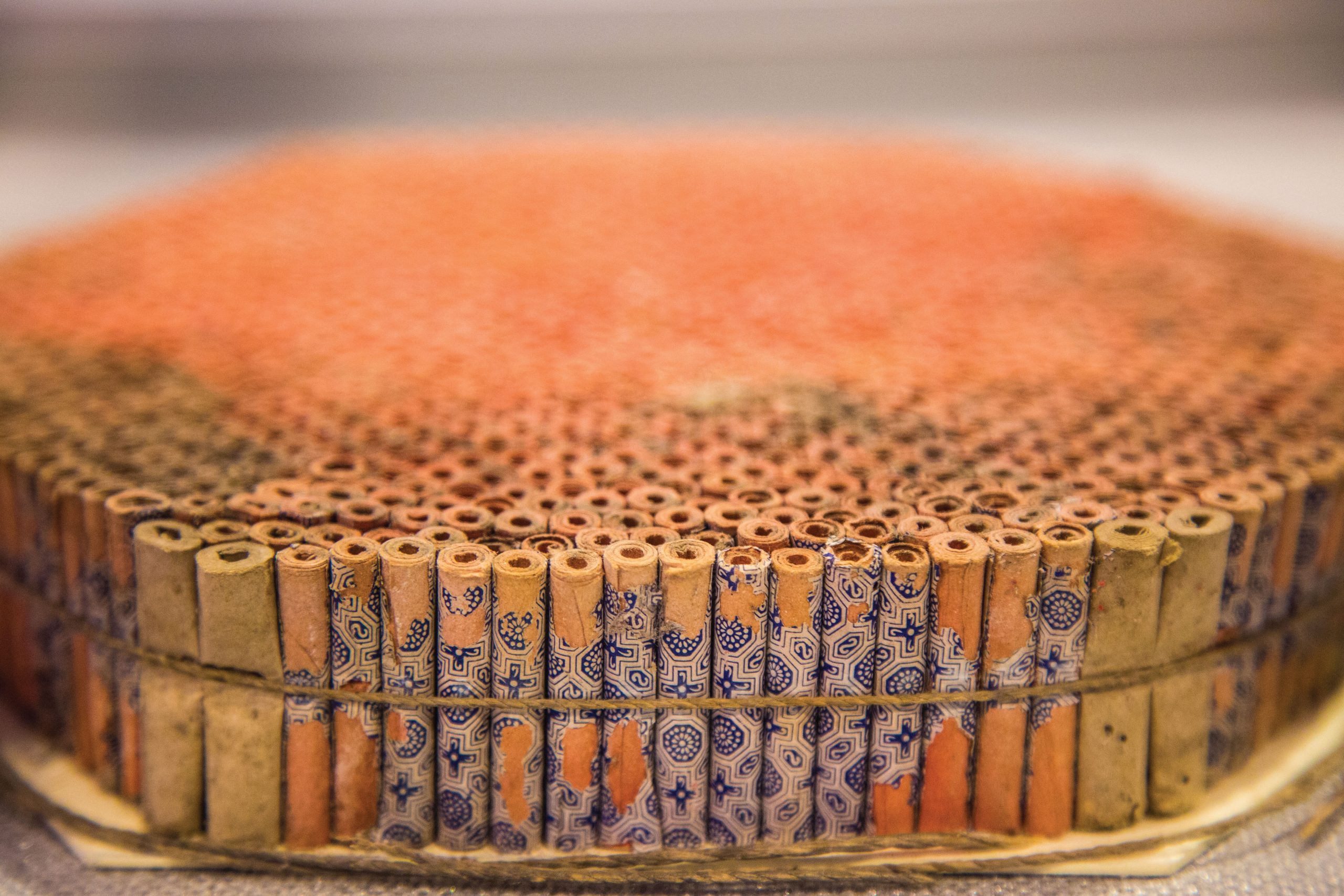

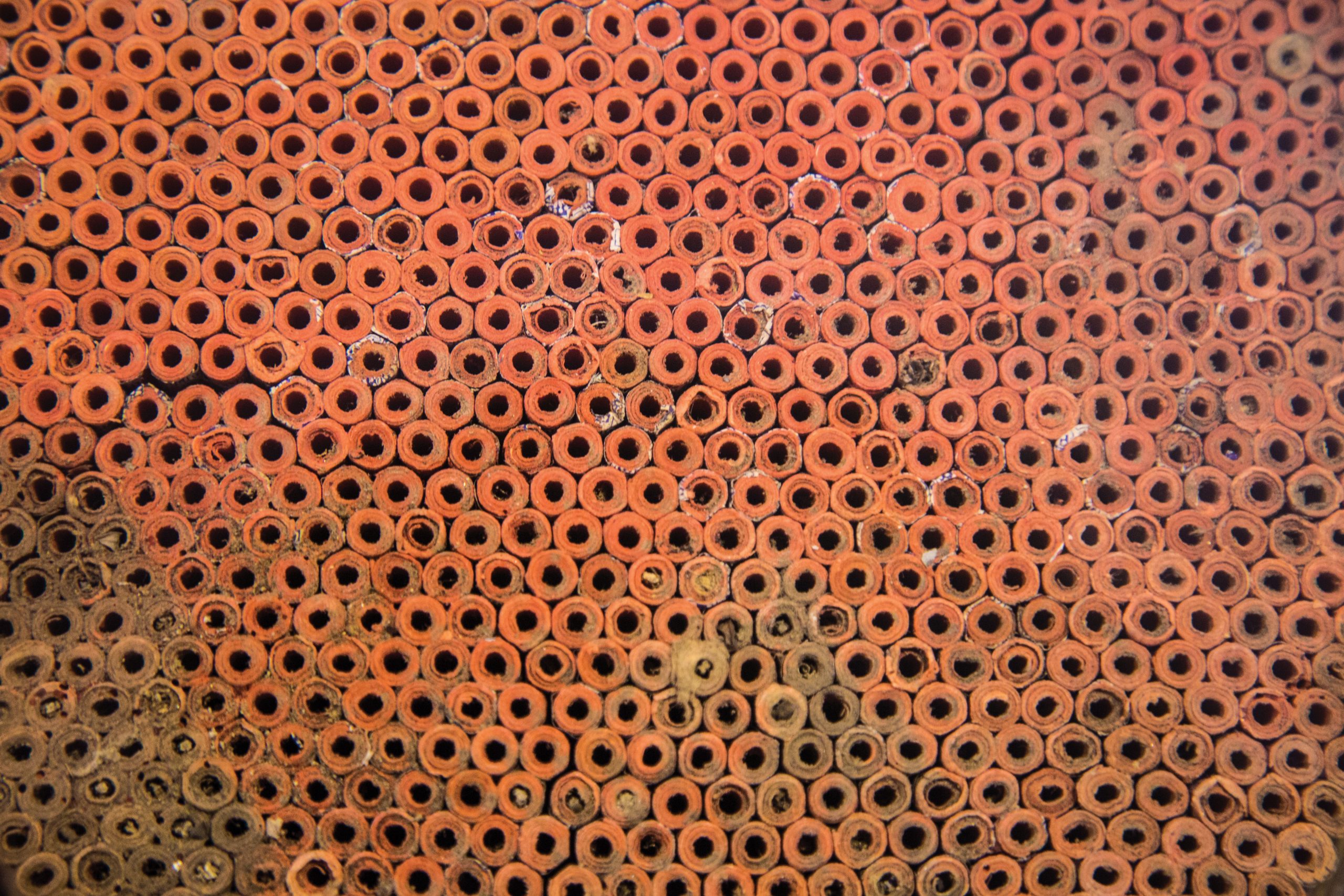

Like incense, the industrialisation of firecracker production began in the 1860s. But manufacturing these small, explosive fireworks proved dangerous for workers. Many of the materials used were highly combustible, making safety procedures a must. Some processes were carried out in the dead of night because the materials would explode if exposed to sunlight. But with few alternative options for employment, the workers, including children, had little choice but to risk it.

In 1925, a devastating explosion at the Toi San factory killed about 150 workers and injured hundreds more; it was one of the most deadly fires in the city’s history. The colonial government ordered companies to move their high‑risk production to Taipa, which became the centre for manufacturing. People in the peninsula were limited to less dangerous finishing work.

The biggest of the six producers in Taipa was Kuong Heng Tai. At its peak, its plant accounted for one‑fifth of the total land area of Taipa, employing thousands of people and producing millions of firecrackers each week. Founded in 1924, Kuong Heng Tai ended operations in 1974, an early victim of the changing economic landscape.

When China and Hong Kong banned manufacturing of firecrackers in the 1960s, Macao’s industry boomed. Local companies exported their products to countries around the world, and played a major role in the local economy. But when those bans were removed and the Chinese market opened to the world in the 1970s, Macao found itself unable to compete against its new, lower‑priced rivals. The last producer, Iec Long Fireworks Company, closed its doors in 1984.

A striking piece of history

The match industry in Macao began later with the first factories opening in the 1920s, decades after the first Chinese factory had opened in Shanghai in 1877. But their late entry likely helped protect workers; early iterations of match manufacturing used chemicals that disfigured and killed many workers.

The Cheong Ming and Tung Hing factories, both established in the early days of the industry, lasted into the 1980s. At its peak, the local match industry produced 1.5 million boxes – 85 million individual matches – each day and employed thousands of workers. While most of the production was done by hand, the bigger plants had mechanical operation.

These plants exported their products to the mainland, Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, Malacca, Mozambique, and South America. The match was an essential item in daily life, for cooking, lighting cigarettes, and burning fuel. It remained so until the invention of the Bic disposable lighter in 1973.

Labels became an important element in the industry as companies competed to create more distinctive and eye‑catching designs. They carried many different images: the name of the factory, religious motifs, patriotic propaganda, animals, plants, and auspicious designs. These tiny pieces of graphic design, reflections of the world around them, are still prized among collectors today.

Like incense and firecrackers, matches retained an element of handicraft in their production. Work done outside the factories – in the homes of residents and on the streets – helped boost the popularity of matches in the city.

Fall of industry

A changing landscape pushed these three prosperous industries into decline, beginning in the 1960s. Urban development in Macao turned open land into homes, hotels and commercial sites, and drove up the price of land. The gambling sector, long present in Macao, began its rise to dominate the city’s economy. Then China opened its doors in the 1970s, its cheap land and low labour costs prompting many manufacturers to move their operations to the mainland.

The 1970s also saw many Hong Kong industrialists set up garment and textile factories in Macao. It was cheaper than Hong Kong, and enjoyed surplus export quotas under the Multi‑Fibre Arrangement (MFA). Many Macao workers moved to these new plants.

The manufacturing sector in Macao peaked in the 1980s, accounting for 40 per cent of Macao’s GDP and 90 per cent of its physical exports. But the success of textiles and garments was short lived: China and Southeast Asia offered cheaper costs and the MFA was gradually phased out, ending on 1 January 2005.

Today, Macao holds few reminders of the traditional handicraft industries that brought the city so much prosperity just two generations ago. To create The Memorable Time, Macao Museum assembled a collection of never‑before‑seen museum pieces, as well as artefacts from private collections and Macao residents, that illustrate a history all but erased from the city’s landscape. In doing so, they offer a truly Macao story – the perfect subject to kick-off celebration of the museum’s 20th anniversary in 2018.