When the Macao government added 55 items to its List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2020, it dramatically expanded the original list of 15 elements announced three years earlier. Each of these 70 elements contribute to the more than 450-year-long story of Macao – as well as having a story of their own. And under the government’s protection, these unique handicrafts, artforms, religious festivals and culinary delights will be safeguarded for generations to come.

The Historic Centre of Macao, especially the area surrounding the Ruins of St Paul’s, is teeming with various intangible heritage elements, including the long-standing practices of herbal tea brewing, incense stick manufacturing and the making of elaborate traditional Chinese wedding dresses.

Taste a nearly 2,000-year-old remedy

Just before evening sets in, Wong Ping prepares his stall Man Ka On along Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro for a rush of afterwork customers. A distinctive aroma wafts through the air as he fixes a lightbulb hanging above six glasses filled with various herbal teas.

Establishing his stall in 1985, Wong has been brewing herbal tea for health-conscious Macao residents for nearly 40 years. He learned Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in his hometown of Shunde, in Guangdong Province, and his wealth of knowledge has made him something of a local expert in herbal tea.

Since setting up shop, Wong has watched the area change yet each street remains very “distinctive”. Wong chose the Ruins of St Paul’s neighbourhood, near Rua da Felicidade, for his stall because of its convenience and popularity – he sees lots of foot traffic every day, which is good for business.

Because his customers “have night shift work,” he says their health can be affected. “Herbal tea can help in this case.” Wong even served Hong Kong actor Simon Yam herbal tea once, and a production crew borrowed his stall for filming.

The various teas are targeted at specific ailments. For instance, Wong recommends sleepless night shift workers opt for Heat-Reducing Tea (降火茶).

The sweet-tasting Five-Flower Tea (五花茶) is best for supporting liver function and protecting the eyes. Dampness-Relieving Tea (祛濕茶), meanwhile, is best for detoxifying the digestive system, improving skin conditions, clearing acne and eliminating halitosis.

The medical theories behind herbal tea can be traced to the Eastern Jin dynasty (317-420 CE), when a Taoist herbalist and physician named Ge Hong moved to southern China and began to study herbal treatments for ailments caused by the humid climate in the region. The earliest records of herbal tea remedies can be found in a clinical first aid manual, Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang, written by Ge Hong more than 1,700 years ago.

While it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when herbal tea shops first appeared in Macao, one of the first was Tai Sing Kung Cha Medicinal that opened near the Ruins of St Paul’s more than 200 years ago – and is still open today.

An ancient handicraft burns on

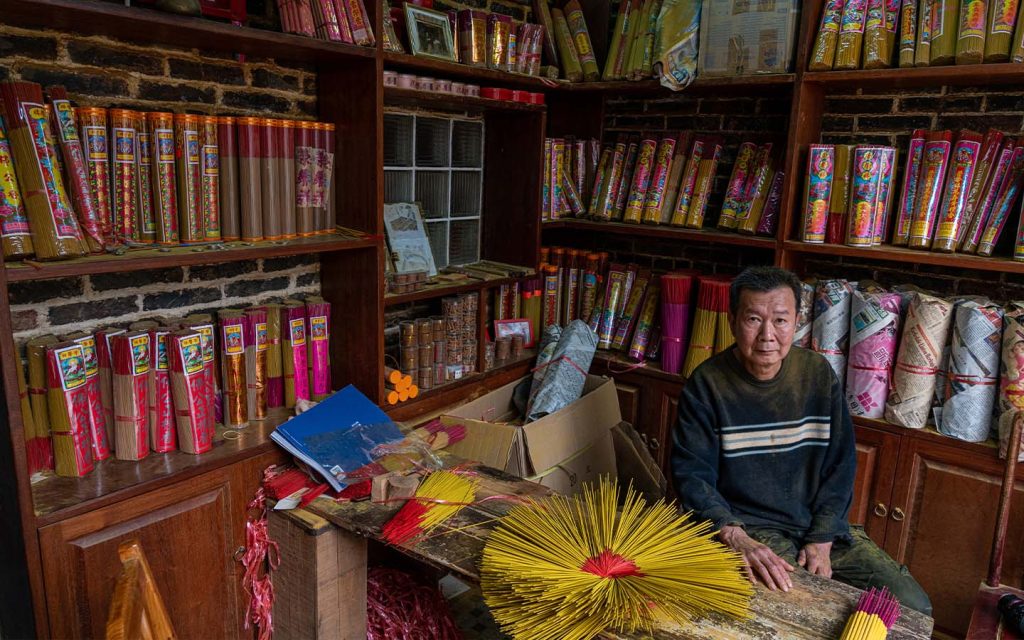

The narrow Rua dos Ervanários is lined with tiny stores selling everything from toys to jade carvings, and even Macao’s own Coca-Cola Museum. This special street is also home to one of Macao’s most important incense stores: Tam Kin Hong’s Veng Heng Cheong Joss-stick Shop.

Jam-packed with pink, red and yellow incense sticks, the store feels like a relic of the past. Tam explains the message behind the name: “My father is Tam Veng, so part of the name is taken from his ‘Veng’. Heng means ‘fragrance’ and Cheong means ‘auspicious’.”

Tam’s family founded the shop in 1968, choosing the prosperous Ruins of St Paul’s neighbourhood because it’s in the heart of the city with plenty of passersby. The store is also close to a few temples – the Na Tcha Temple, behind the ruins, and the Hong Kung Temple on Rua de Cinco de Outubro – making it convenient for customers to purchase joss sticks before worship.

Tam learned the trade from his parents when he was in middle school. “I started learning how to make incense by going with my mother to the factory.” Since then, he’d spend all of his school breaks learning the trade. He later enhanced his techniques by apprenticing with a master incense maker at the age of 17.

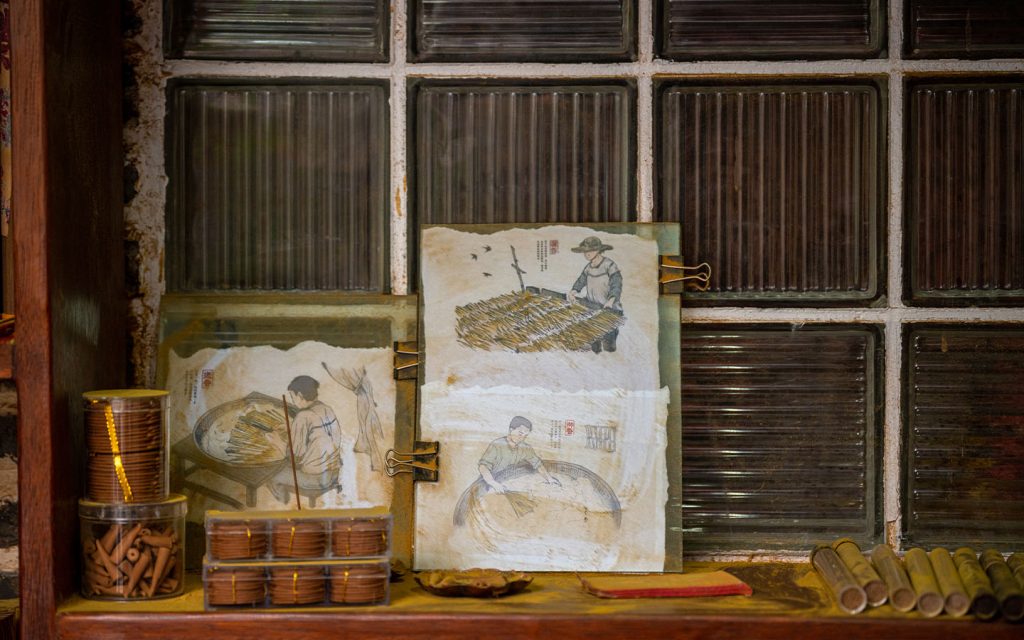

Crafting incense sticks, which are usually made from sandalwood or agarwood, by hand is more complicated than one might imagine. In fact, there are three distinct methods. The first, called cuoxiang, requires the artisan to knead a mixture of sawdust, spices and incense powder onto bamboo sticks until they’re fully coated.

The second, linxiang, sees craftsmen dip a bundle of bamboo sticks into water, then into a mixture of incense powder three times before being left to dry. And the third uses machinery – the most recent development in the trade. “While there are three ways to make incense, I learned to craft two kinds: cuoxiang and linxiang. In our store, our incense sticks are cuoxiang-made [by artisans in the mainland].”

Incense stick manufacturing in China emerged from the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-221 BCE) onward, reaching greater heights during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). In Macao, the industry thrived during the 20th century, with 17 factories known to have existed by 1910.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the manufacturing of incense sticks was one of Macao’s three main industries – right behind matchsticks and firecrackers. At the industry’s height, there were more than 40 incense factories.

Veng Heng Cheong is one of a handful of remaining joss stick shops in Macao. Another is Fábrica de Pivetes Lei Cheong Heng, on Rua do Almirante Sérgio. Tam, who’s in his mid-seventies, pledges to keep the tradition going so long as he is in good health.

Stitching a beautiful tradition

Just around the corner from Veng Heng Cheong Joss-stick Shop, along Rua dos Mercadores, stands Choi Sang Long Embroidery. With more than 100 years of history, this is one of the few remaining traditional Chinese tailors in Macao that still crafts traditional Chinese wedding dresses (known locally as kwan kwa) by hand.

The store’s third-generation owner Wong Weng Sou says he can’t remember exactly when the store opened, but pulls out a laminated invoice dating all the way back to 1913.

“I only know that it has been more than a hundred years because this shop was opened during my grandfather’s generation,” he says, adding that his grandfather was originally the master dyer and took ownership of the store 80 years ago.

“Choi means ‘different colours’; sang, ‘business’; and long, ‘prosperity’,” he continues, explaining the store’s name. From outside, the shop’s display of embroidered red kwan kwa captures the attention of brides-to-be. Inside, one can sift through reams and reams of fabric, all protected by special coverings.

In Wong’s grandfather’s time, the store was a dyehouse. Then in the 1970s, the family changed directions and became a bridal store selling both Western-style formal wear and traditional Chinese dresses.

The traditional bridal ensemble features two pieces – a long skirt known as the kwan and an upper gown called the kwa with buttons down the front and the handmade, intricate embroidery that takes several months to create. First, tailors measure the client, then cut the fabric, draw patterns, build the structure, refine, and finally hand-stitch the embroidery.

The embroidered designs tend to take on symbolic patterns, such as a flying dragon sewn with glistening golden thread alongside a gold or silver phoenix, which together signify eternal love. Often, the skilled tailors also weave clouds, flowers and other patterns into the designs – each with its own meaning. “For example, the flowers represent the blossoming of wealth and honour,” Wong says.

“In the past, we also made beaded gowns and skirts,” he continues. “Nowadays, most of our customers prefer gold and silver thread. In the past two decades, they’ve also asked for three-dimensional designs, enhancing the quality of the dress.”

They are worn during the traditional tea ceremony, an important part of Chinese weddings spent with senior family members. Naturally, the more elaborate the embroidery, the more expensive a dress will be.

The dresses aren’t restricted to weddings. “Sometimes on happy occasions, large families will wear traditional clothes to take photos during the New Year,” agrees Wong. “However, this is less common.”

One of the only stores left in the city doing traditional Chinese wedding dress embroidery, Choi Sang Long’s clientele includes many locals and even orders from abroad. It is proud to preserve the artform in Macao, and its location near a cakeshop and Che Lee Yuen – a local gold and jewellery store dating back to the 1860s – is a boon for business. “We create such beautiful clothes for brides,” says Wu Lai Heng, Wong’s business partner and wife. “Everyone is happy when they have an unforgettable wedding.”