On a hillside in the centre of Macao lies a plot of ground that is an important piece of the city’s history – the Old Protestant Cemetery in which 162 people of different nationalities are buried, including some of the most famous foreigners who ever lived here.

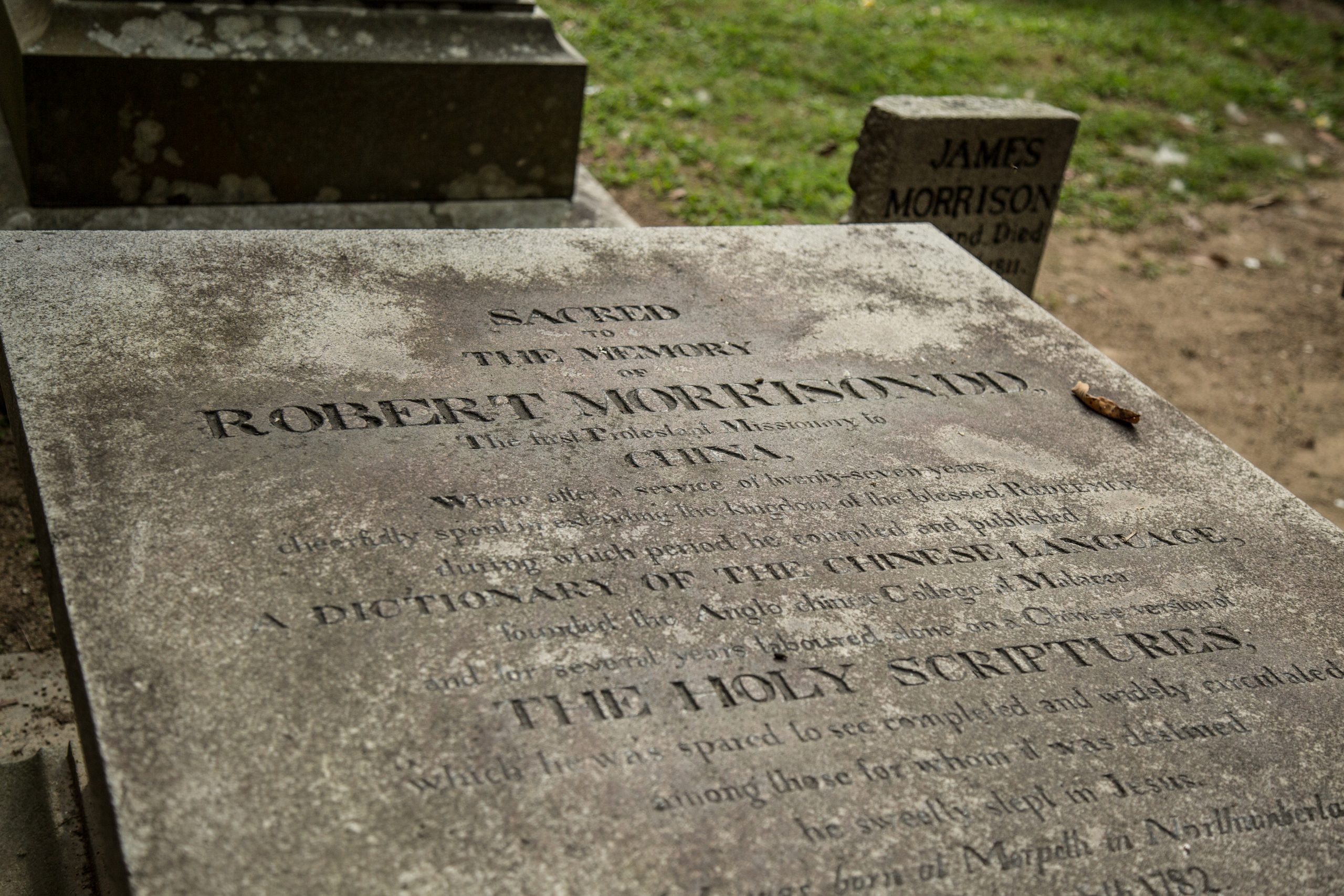

They include Robert Morrison, the first Protestant evangelist to China, and his friend, George Chinnery, the best‑known Western painter in the city, and Captain Lord Henry John Spencer Churchill of the Royal Navy, the brother of the great‑grandfather of Sir Winston Churchill. These three memorials are the most frequently visited.

Others buried here include American naval and merchant personnel, British and American missionaries, Joseph Adams, grandson of the second president of the United States and nephew of the sixth president of the United States, soldiers, merchants, sailors, doctors, diplomats and civil servants. There is Captain Christian Jpland, a Danish sea captain, Sandwith Drinker, an American sea captain, businessman and consul, and many children of the expatriate community.

While British and Americans account for the majority of the people interred here, the site also includes French, German, Danish, Dutch, Swedish and Armenian people. Few died of old age. Most fell from the diseases of the tropics, such as malaria, cholera, typhus and dysentery. Other deaths were caused by drowning, being killed in battle, committing suicide and also victims of murder.

Sir Lindsay Ride, one of the most distinguished historians of Hong Kong and Macao, wrote this about the cemetery:

“The interest is not by any means confined to biographies of those buried there. There are the histories of the ships that brought them there, clippers, men of war, whalers and countrymen (vessels serving India, Southeast Asia and Guangzhou): there are the interesting professions they followed as merchants, missionaries, military men, beachcombers, diplomats or opium traders, there are the mysteries behind the nameless memorial or the undecipherable or partly decipherable inscription, or the absentees.”

The cemetery is next to Morrison Chapel, named after the famous missionary of the same name. The chapel was probably built soon after the opening of the cemetery, with the first recorded marriage there in 1833. In 1921, the chapel was completely rebuilt, with two conditions – it be hidden from the street by a high wall and a bell was not allowed to be installed in the rebuild. The building work was completed in 1922 and the chapel remains in use today.

Stay out of the city

In the early years of Macao, the Portuguese authorities refused to sell land to non‑Catholics for use as a cemetery. This meant that those who had lost their loved ones had to bury them on hillsides outside the city walls.

Further up the Pearl River, burial of loved ones was easy and convenient. The Chinese had no such thing as enclosed cemeteries; there were no legal or civil procedures required to conduct a burial. All that a person needed to do was to negotiate with a Chinese landowner and hire a few labourers.

In the second half of the 19th century, the number of non‑Catholic foreigners in Macao continued to grow, including those who worked for the British East India Company (EIC), which represented the most powerful maritime trading power of that time. Due to the poor hygiene conditions and limited medical care, a portion of these foreigners died in Macao. As a result, the pressure on the Portuguese authorities increased.

Finally, in 1821, with the death of Mary Morrison, the wife of Dr Robert Morrison, the government finally relented and agreed to let the EIC have land for burial purposes.

During her final illness, Mrs Morrison expressed her wish to buried with her firstborn son James, who had died 10 years before, and who had been buried on a Chinese hillside. But the Chinese were reluctant to open an old grave.

Pressure from the EIC and the popularity of the Morrisons persuaded the government to sell a plot of land near one of the EIC’s official residences for use as a cemetery. Later the EIC allowed all foreigners to use it.

Some people sought permission for the remains of those buried on hillsides to be moved into the new cemetery. As a result, some of the gravestones show dates of death earlier than 1821. It contains people belonging to different denominations of the Protestant religion, including Baptists, Methodists, Quakers and Presbyterians.

For their relatives, it was important that their loved ones be buried in holy ground, close to a church and next to others of the same faith – and not on an anonymous hillside where no one knew them and no one would come to remember them.

In 1858, the Portuguese authorities decided that no more burials were to take place within the city and the cemetery was closed. The Protestant community purchased another plot near Carneiro’s Garden, which came to be known as the “new cemetery, and a board of trustees was put in charge of it.”

When the EIC ceased operating in China in 1834, its property in Macao came under the ownership of the British government. In 1870, the trustees of the new cemetery were given charge of the old cemetery as well.

In 2005, the cemetery was included as part of the Historic Centre of Macao, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Famous and anonymous

The cemetery, which contains both the famous and the anonymous, is a reminder of the fragility of human life. A famous name and a great fortune cannot save a person from an early and unexpected death. “Sic transit gloria mundi” – “so passes the glory of the world.” This was a phrase used during the coronation of the Pope for five and a half centuries, to remind the incumbent that all his baubles would not save him from the tolling of his final bell.

An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China & Description of the City of Canton

Some people just passed through Macao while others made it their home. Among them was Anders Ljungstedt, a Swede who moved to Guangzhou in 1798 and worked as a trader for the Swedish East India Company.

In 1815, he settled in Macao, and made it his home, setting up his own business. He was decorated by the Swedish King and in 1820 became the first consul general of Sweden in China. He never returned to his native country, but donated most of his wealth to his home town of Linkoping, to build schools for the poor. He is also buried in the cemetery.

Ljungstedt took a great interest in the history of Macao and wrote “An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China & Description of the City of Canton.” It was published in Chinese in 1997. A high school in Linkoping bears his name and an avenue was named after him in Macao in 1997.

In the early years of Macao, the Portuguese authorities refused to sell land to non‑Catholics for use as a cemetery. This meant that those who had lost their loved ones had to bury them on hillsides outside the city walls

More than 50 Americans are buried in the cemetery, including the two daughters and uncle of James Bridges Endicott, a direct descendant of John Endicott, who sailed on the ship Abigail from Weymouth, southern England, to the New World and became the founder and first governor of the state of Massachusetts.

James Endicott was born in Danvers, Massachusetts in 1814 and lived for 35 years in Hong Kong, Macao and Guangzhou, before dying of typhoid in 1870. He was a company director of Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Co. Endicott is buried in a cemetery in Happy Valley, Hong Kong, but has a memorial in Morrison Chapel.

On arrival in the Far East, Endicott worked for the American trading firm Russell & Co. and was stationed near Macao. In 1854, he went into the business of ship‑chandlery, ships and dockyards with a partner. An enterprising and adventurous merchant, he earned and lost a great fortune. Endicott had several children with a Chinese concubine before he married a woman from England in 1852.

Another American is Joseph Harrod Adams, a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, and the grandson of the second president of the United States, John Adams. He died on 4th October, 1853 in China at the age of 35 on board the American ship Powhatan, which was part of an expedition to Japan. He was buried in Macao.

Preaching the Gospel

The most famous missionary there after Robert Morrison was Samuel Dyer. He was born on 20th February, 1804 and sent to the East by the London Missionary Society in 1827. He died in Macao on 24th October, 1843. This is the inscription on his tombstone:

“The Rev Samuel Dyer Protestant Missionary to the Chinese who for 16 years devoted all his energies to the advancement of the Gospel among the emigrants from China settled in Pinang Malacca & Singapore. As a Man, he was amiable & affectionate, As a Christian, upright, sincere, & humble‑minded; As a Missionary devoted, zealous & indefatigable. He spared neither time, nor labour, nor property, in his efforts to do good for his fellowmen. He died in the confident belief of that truth which for so many years he affectionately & faithfully preached to the Heathen.”

Dyer, who spent his missionary years in Penang and Malacca, died in Macao while on his way to a new assignment in Fuzhou, capital of Fujian Province in China.

One of Dyer’s many achievements was to produce movable metallic type for the printing of Chinese characters of high quality. He used these to print Bibles, tracts and books.

Another important historical figure was William John Napier, 9th Lord Napier, an officer in the British Royal Navy who served as a midshipman at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. In December 1833, the foreign secretary sent him as Britain’s first chief superintendent of trade at Guangzhou. He later settled in Macao, where he lived in a large and spacious house.

In August 1834, Napier was the first British representative to propose the seizure of Hong Kong. He also sent warships to attack Chinese positions in Guangzhou. But his lack of diplomatic finesse, misunderstanding of Chinese protocol and missteps resulted in the failure of his mission to expand British trade.

Napier caught typhus and died on 11th October, 1834 in Macao and was buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery. His coffin was later exhumed and he was reburied at Ettrick, in the Scottish Borders region of Scotland.

A fellow British naval officer was Captain Lord Henry John Spencer Churchill, the brother of the grandfather of Sir Winston Churchill. He was promoted to naval captain in 1826 and in 1839 he commanded The Druid on service in the East Indies. In January 1840, the Druid arrived in Macao to join the British fleet assembling for the first Opium War.

However, Churchill fell sick of dysentery and died in the city on 3rd June, 1840. He was buried in the Old Cemetery two days later.