Ahoy there me hearties! The Archives of Macao has opened an exhibition on pirates that uncovers historical treasures around the city’s shores. We speak with one of the learned landlubbers behind this spellbinding swashbuckling show.

Pirates have been romanticised over the years. We love to dress up as swashbuckling adventurers at costume parties and we adore watching certain wildly popular Hollywood blockbusters based on the theme of piracy. But not too long ago, pirates were anything but romantic. They were often seen as menaces, roaming the high seas looking for treasures. But they were also often integral parts of society and thus are now integral parts of history. Macao, in the second half of the 19th century and into the 20th century, was as plagued by these seafaring vagabonds as much as anywhere else in the world which had a coastline and a steady stream of trading ships regularly sailing past with plenty of riches onboard.

Many people in Macao probably don’t know about the city’s old battles with piracy. Which is why, after four years of planning, the Archives of Macao has set up a special exhibition to teach locals all about the SAR’s swashbuckling past. The Archives, a treasure trove in St Lazarus’ Parish which collects, processes, protects and makes old records available, has organised ‘Pirates in the Waters of Macao (1854-1935)’, an exhibition that seeks to educate the public as simply as possible on a subject that is actually much more complex than you would think.

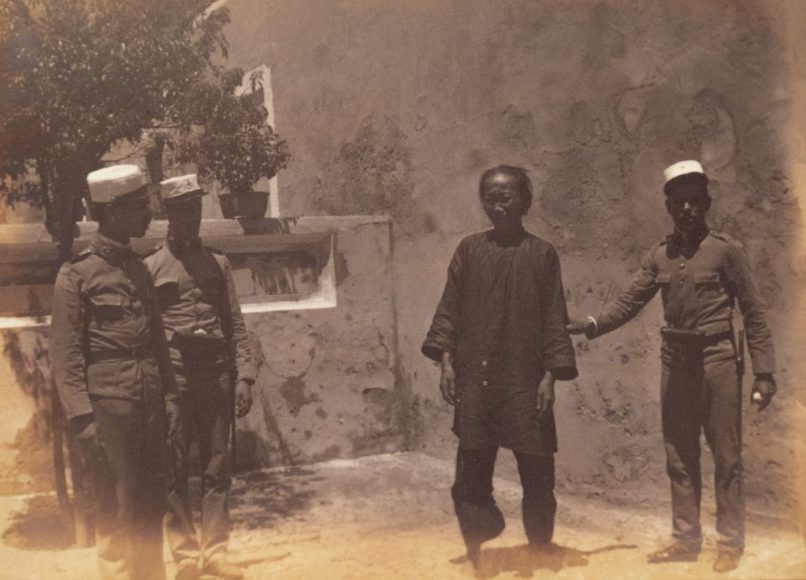

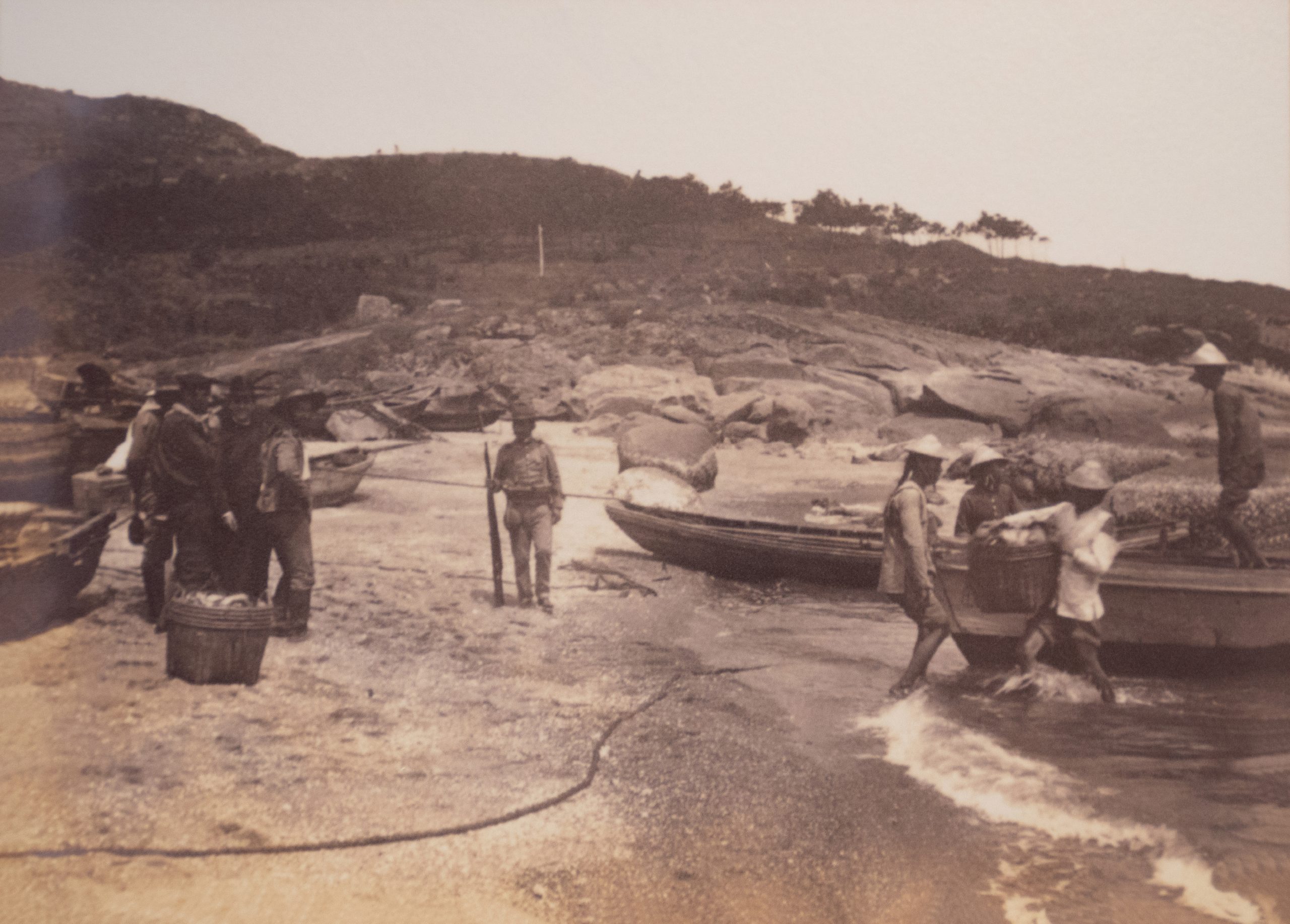

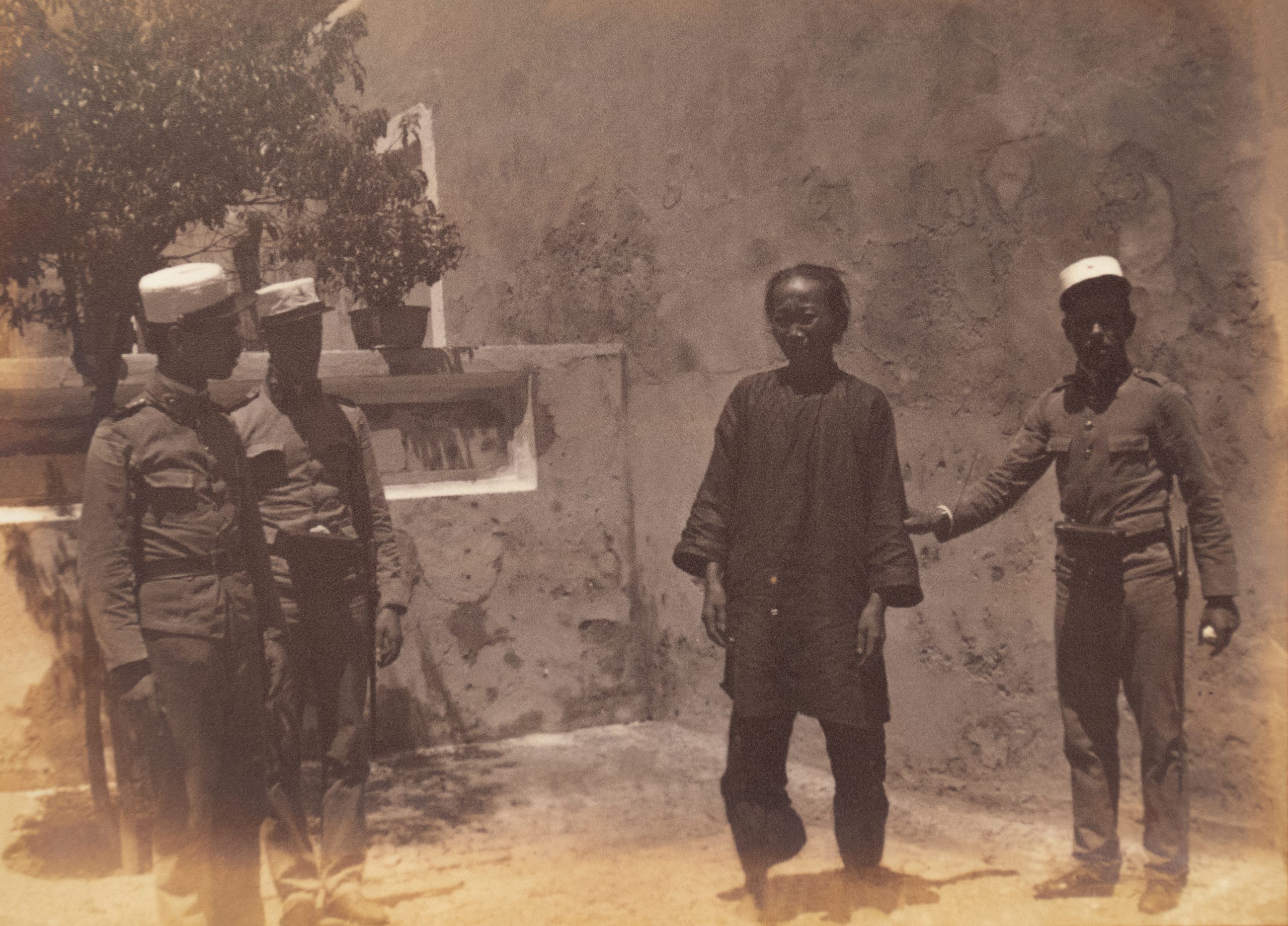

The exhibition, which opened last month and will be running until 31 January, features a selection of more than 100 preserved documents, maps and photographs documenting piracy in Macao’s waters over many decades. To help us give a better flavour of the exhibition, we speak with the Archives of Macao’s head researcher Alfredo Gomes Dias, who illustrates the significance of pirates in the city’s long history. He says that piracy was a political, economic, social and cultural phenomenon in Macao from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century. And, now we’re in the 21st century, this part of history is more than worth learning about as it helped shape the city we know today…

How long did it take to put this exhibition together?

I started working on this exhibition in July 2016 with the help and dedication of the entire Archives of Macao team. The work was organised into three phases. The first phase focused on document collection. This meant the identification and selection of archive files related to piracy, as well as the transcription of more than 400 documents which we gathered into two volumes for the exhibit. This was followed by the construction of a catalogue to accompany the exhibit. This catalogue – part of what’s called the Document Collection – doesn’t just present the documents but it also includes a study that gives clues for further research on the subject. Finally, the third phase consisted of defining the concept and planning the exhibition which was to be presented to the public, as well as fine-tuning the selection of documents to be displayed. It took us four years of intense and passionate work.

Tell us about Macao’s pirates…

This exhibition is about a social group that was organised into different communities, each with their own hierarchy, living on Macao’s water-lines and the surrounding islands, scattered throughout the Pearl River Delta region. Despite exclusion, the pirates did not fail to interact with society, from their victims and accomplices to the political and military power that repressed them. It is worth remembering that their actions also transformed them into silent victims of the political and social powers of Macao, Hong Kong and Canton [now Guangdong]. Organised thematically, the exhibit presents an array of different ways to analyse the presence of pirates in Macao. It enlightens us not only about the geopolitical impacts of piracy but also the economic and social impacts. While they remained silent for so long – as all documents are essentially the version of history that those in political power and social elites of the city maintain – this exhibition is a way to give them visibility. Studying this social group and documenting their part in history finally gives them a voice.

Are there any surprising pieces in the exhibition?

The documents that are most surprising are the letters written by the pirates themselves, which can be read in the original Chinese as well as Portuguese translations. However, the richest documents are the reports prepared by the Portuguese military in their joint expedition with the Canton military forces in 1912 to the islands of Dom João and Montanha [which have since been joined and now make up Hengqin Island]. They made very interesting descriptions of the islands’ terrain, climate and vegetation, as well as their military actions. These cartographic illustrations themselves are small pieces of art. These documents also illustrate an interesting episode of collaboration between the Portuguese and Chinese military forces in the fight against piracy. Due to contention over the claims of these two islands, the two countries planned a simultaneous landing to ensure this initiative would not be used diplomatically by either country to claim ownership of the islands. The description of the meetings between the two forces and joint statements of the two military groups are particularly revealing of the ability of the representatives of Portugal and China to establish a friendly relationship when they came together around a common objective.

What pieces were a challenge to acquire for the exhibition?

Aside from all the documents, photos and maps that are already part of the Archives of Macao’s documentary assets, we also found news about piracy published in newspapers. While some newspapers were accessible at the Archives of Macao, we also consulted titles in other archives and libraries, both in Macao and Lisbon. We collected dozens of news items about the incidents of piracy that occurred at sea or on the streets and seasides of the city. The most relevant records, in addition to those already on display, have been compiled in the Document Collection [owned by the Archives of Macao].

What is the significance of this exhibition in Macao?

It addresses a particularly relevant topic that is strangely underdeveloped. Macao’s social history still has many areas that need to be developed if we want an in-depth look at Macao. The most important thing in the study of Macao’s history is getting to know its people from different backgrounds who were engaged in an array of activities and who built this city over the past five centuries. The pirates also made their contribution to Macao’s social fabric.

What are the key takeaways for visitors to this exhibition?

Each person who visits the exhibition can draw their own conclusions. In general, we would like everyone to better understand the complexity of this issue and not to reduce pirates simply to a band of criminals. It is important they are recognised as human communities. Although they were peripheral social groups, they nevertheless maintained bridges with societies. [This exhibition was] conceived to inspire those who study the past and present of Macao, in its many areas, and we hope to encourage new investigations into the pirates in the waters of Macao.

Get to know

Alfredo Gomes Dias

Archives of Macao head researcher

Dias, who hails from Lisbon in Portugal, began his studies on Macao history in 1987, visiting the city for the first time in 1994. At the time, his research focused on its modern history, particularly mid-19th century Macao. In 2008, he started visiting Macao once or twice a year as he began his PhD research on the ‘Macanese diaspora’ and the ‘Portuguese from Shanghai’ community. His constant presence as a researcher at the Archives of Macao opened the door to this recent collaboration. Lau Fong, Archives of Macao director, invited Dias in 2013 to begin his research for the ‘Shanghai Portuguese Refugees in Macao (1937-1964)’ exhibition, which was inaugurated in 2015 and was also presented in Portugal, in the cities of Lisbon and Guimarães. Afterwards, he collaborated on the Archives of Macao and National Archives of Torre do Tombo (Lisbon) joint exhibition called the ‘Chapas Sínicas – Stories of Macao in Torre do Tombo’.

Lau Fong

Archives of Macao director

Director of the Archives of Macao for more than eight years, Lau is a graduate of history who devoted several years to the collection ‘Official Records of Macao during the Qing Dynasty (1693–1886)’. This collection received global recognition in 2016 by the United Nations. Her competent understanding of the classical language – which is substantially different from the modern Chinese introduced in the mid‑1910s – helps her get to grips with classical documents. In 2013, she invited Dias to work on an exhibition at the Archives of Macao: the ‘Shanghai Portuguese Refugees in Macao (1937-1964)’. This was the start of the collaboration with Dias.

Fong says that the current exhibition on pirates ‘is part of the Archives of Macao’s strategy to promote and enhance its role in the study of the city’s history through documentary findings’. She says: “In fact, the Archives has presented many exhibitions in the past on a range of different themes to demonstrate its great variety of documents. An exhibition is often an effective way of developing archival resources. It is also a significant approach to raise public awareness of archival culture and preserve the collective memory of society. The Archives of Macao will continue to organise exhibitions on different themes and draw upon the richness of its holdings to promote the history, culture and identity of Macao.”

Pirates In The Waters Of Macao (1854-1935)

The exhibition at the Archives of Macao runs from 10 am to 6 pm daily, except on Mondays and public holidays, until 31 January. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, facemasks are required, as well as a temperature check and showing the visitors’ Macao Health Code results upon entry. For details, call +853 2859 2919 or email readingroom.ah@icm.gov.mo.