In the aftermath of World War I, aeroplanes began to rule the skies.

Following French pilot Louis Blériot’s historic crossing of the English Channel in 1909, the first public flight took place in February 1919. Soon, major powers, seeking to enhance their colonial prestige, began undertaking long-distance air travel – Portugal included.

Three Portuguese aviators – pilots Sarmento de Beires and Brito Pais and mechanic Manuel Gouveia – aimed to leave their own mark on aviation history.

The aviators attempted to fly from Lisbon to Madeira aboard the Black Knight in 1920 but failed. Undeterred, they regrouped and redirected their efforts towards the South Atlantic crossing. However, Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral had beaten them to it in 1922. And so the aviators shifted their focus once more, this time to Macao.

Departing 7 April 1924, the pilots this time would make history.

Although their small aircraft eventually crashed in China, brought down by a typhoon just 800 metres from the Hong Kong border, their journey was nevertheless a success. It demonstrated not only the increasing capabilities of aeroplanes for long-distance travel, but also the determination and pioneering spirit of early aviators.

Bumpy skies ahead

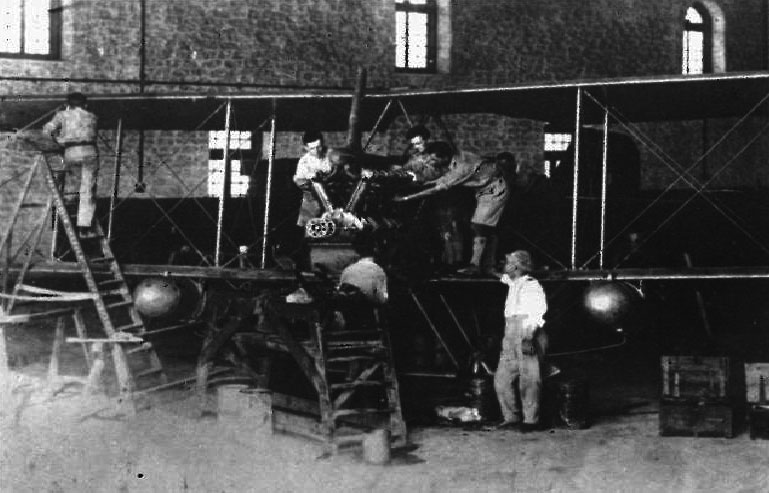

For the voyage ahead, the three men elected to fly a Breguet 16 Bn2, equipped with a 300 horsepower engine and additional fuel tanks to extend its range.

Manufactured at the workshops of the Grupo de Esquadrilhas de Aviação República in Amadora, near Lisbon, the plane was christened Pátria (‘motherland’), the name proudly displayed on its fuselage.

In the early hours of 7 April 1924, the Pátria, piloted by Beires and Pais, took off from Milfontes, in the south of Lisbon. Gouveia, their mechanic, joined them later in Tunis.

The pilots got caught in a storm, which forced them to fly at a low altitude over the Bay of Algeciras and make an emergency landing in Málaga. It was the first of many life-threatening challenges they would face.

“The engine failed due to a lack of gasoline, which, due to inertia, did not flow through the pipes,” Beires wrote in the flight logbook.

Two days later, they arrived in Oran – a key aeronautical centre in Algeria – at La Sénia airfield, where they were welcomed by military aviators.

On 12 April, the Pátria, escorted by two French planes, continued its journey to Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, where it landed six hours later at Kassar Saïd airport. From there, Gouveia would join them for the rest of the voyage to Macao.

On 14 April, the three set course for Tripoli, in modern-day Libya, flying over the desert.

Beires vividly described the scene. “To the northeast, the houses of Tripoli shone in the sunlight. And as we approached, the city was a surprise, an amphitheatre over the sea, with a port – two granite arms embracing a small body of water – some ships, and the sandy airfield, six kilometres to the east, in a clearing surrounded by palm trees.”

They rested for two days and resumed their journey on 16 April. However, strong winds forced them to make an emergency landing in Al-Khums. Two days later, the weather improved, and they set off again for Benghazi.

At an altitude of 2,400 metres, they were suddenly caught in a sandstorm. “It was dangerous to descend. The heat, the sand, the thin air could force us to land. For a moment, I lost the sense of the aircraft’s horizontality. The red mist and the burning light of the sickly sun made me dizzy … When we reached the bottom of the gulf, we experienced horrible moments. We lacked air. We drank water every minute. Our blood throbbed violently in our veins,” wrote Beires.

Their ordeal finally ended when the wheels of the Pátria touched down on the Benghazi airfield after a 900-kilometre flight.

The race to make history

On 20 April, the Portuguese airmen continued their journey towards Cairo – a day after an Englishman named Archibald Stuart-MacLaren had departed in an attempt to circumnavigate the world. No one was waiting for them upon arrival – the telegram sent from Benghazi arrived late – yet this was a momentous occasion.

Upon arriving in Cairo, the Pátria became the first Portuguese plane to cross North Africa.

Leaving Egypt would prove to be a challenge, however. On 23 April, while taking off, the plane burst a tire, damaging the landing gear. Since no replacement was available, they decided to use the landing gear from an English plane, a DH.9 that closely resembled the Breguet 16.

When they resumed their journey, they flew towards Rayak, Lebanon. Leaving behind Suez and Palestine, the Pátria flew smoothly at an altitude of 600 metres, passing over Lake Tiberias, Beirut and the picturesque mountains.

On 26 April, the aviators left Riyaq, cruising at an altitude of 2,700 metres as they made their way toward Baghdad. After a two-hour journey, they landed in Iraq. Around the same time, French pilot Pelletier Doisy also arrived. He was en route to Tokyo – one of many attempts in that time to push the boundaries of aviation science and human experience.

For the Portuguese, the next leg to Bushehr, in Iran, would prove challenging both physically and logistically. Intense heat battered the aviators over the 900-km journey. Their departure was briefly delayed as the authorities required a visa to leave the airfield, a matter resolved with the exchange of a few rupees.

On 2 May, they landed in Bandar Abbas, Iran, after flying 670 km, and spent the night at the residence of the English consul. The next day brought new challenges, including a flight across the hostile desert.

Shortly after takeoff, they encountered a sandstorm. “Heaven and earth disappeared before our eyes. A strange mist of sand and water vapour, driven by the furious lashings of an angry, tremendous wind, enveloped the Pátria as it entered like a train into a tunnel,” wrote Beires.

The crew managed to navigate through the sandstorm, and as they approached their destination, the weather improved. After a gruelling six-hour flight, they touched down at the scorching Drigh Road airfield in Karachi. The worst was yet to come.

A nearly fatal attempt

Early the next morning, the Pátria took to the skies, facing unfavourable weather conditions yet again.

“Visibility worsened with each passing moment. Despite our attempts to climb to a higher altitude in search of cooler air, the Pátria began to descend slowly, unable to sustain itself in the rarefied and scorching atmosphere.

“Gouveia struggled to breathe, while Pais perspired profusely. I summoned all my remaining energy and nerves to keep fighting, but by [10:35 am], we found ourselves just 300 metres above the ground. The descent intensified amidst a sandstorm. Exhausted and aware of my own state … we made the decision to land. Near a native village, I spotted a well-defined sandy area. I reduced the engine power and prepared for landing with the last ounce of energy I had left,” Beires wrote.

As they neared the ground, a powerful gust of wind engulfed the plane, causing it to break upon impact. The aviators, miraculously, escaped unharmed. Locals from a nearby village helped them transport the wreckage to a train station. Their journey had come to a halt outside Jodhpur in India’s Thar Desert.

The journey to Jodhpur, where the Pátria was originally scheduled to land, took two hours on a sweltering train. Out of courtesy and tradition, the city’s maharaja (Hindu monarch) accommodated the aviators in his palace. Despite the regal surroundings, the three were restless. They wondered how to proceed with their mission.

Telegrams flew back and forth between Lisbon and Jodhpur. Portugal promised to provide another plane, a de Havilland DH.9A, and reiterated its commitment to the mission.

However, waiting for a replacement plane would entail significant delays. Instead, the pilots suggested purchasing another plane in India. Lisbon supported the idea, and the journey continued.

Soaring to new heights

They acquired the de Havilland aircraft for 4,700 pounds while what was left of the Pátria was packed and sent back to Lisbon.

On 30 May, the new plane, named Pátria II, took off in the early hours of the morning, heading towards Ambala in the Indian state of Haryana. During the two-hour flight, an English military plane flew nearby so that its pilot provided operating instructions.

On 1 June, Pátria II arrived in Calcutta, after a calm journey of 850 km over the fertile Ganges region and the Parasnath hills. The sailing was smooth again, but not for long.

The aviators arrived in Rangoon, Burma (now Yangon, Myanmar) on 6 June, after flying over the perilous Arakan Mountains. But the landing in Rangoon, on a horse-racing field, proved as challenging as flying over the mountain range.

Beires described making three attempts at landing, manoeuvring the aircraft lower even than the gilded Shwedagon Pagoda while skillfully avoiding a web of telephone wires.

Three days later, the Pátria II touched down in Bangkok without incident, as the final stages of their expedition neared.

The final stretch

Setting off early on the 12 June from Ubon Ratchathani, they embarked on a nearly 900-kilometre journey to Hanoi. As they flew over the South China Sea, the engine began to falter. Concerned, Beires and Pais considered making an emergency landing. But they carried on, determined to reach their destination.

The weather conditions worsened, and visibility diminished, forcing them to navigate carefully over rice fields. Landing in these fields came with the risk of overturning the aircraft.

After a tense flight, they landed in Son Tay, near Hanoi, around midday. To ensure they didn’t lose visibility, they had to fly just 20 metres above the ground during the final phase of the flight.

On 20 June, they made their final push, departing for Macao, more than 1,000 kilometres ahead. Leaving Tonkin Bay with its brownish cumulus clouds behind, they flew with a sense of determination and anticipation. The engine operated admirably, and the weather looked clear.

Suddenly, the plane encountered increasingly intense showers, forcing them to climb to 2,800 metres in an attempt to escape the storm. The weather did not improve, and both the voltmeter and generator stopped working. Seizing an opportunity when an opening appeared in the cloud cover, they descended closer to the ground.

Amidst the relentless downpour, they broke through to the Isthmus of Macao, flying over Ilha Verde and Portas do Cerco. There was just one task to complete: land the plane.

In the inclement weather, their odds of landing safely were low. Pais informed Beires that they should head north towards Canton. But the strong winds made it impossible, and they had to alter their course to the east, towards Hong Kong.

It was a harrowing experience, lasting a mere five minutes. In the typhoon, the Pátria II was tossed around like a leaf in the wind. The engine gradually lost power until it stopped, exhausted. Flying over the railway line to Canton, they prepared for a forced landing.

The pilots found a small field near a Chinese cemetery and took a leap of faith, coming to a stop in just 100 metres. The plane hit a hedge, causing damage to the propeller and landing gear. The Pátria II could fly no longer, but it had taken the aviators to Asia.

Leaving their mark

Although they were unable to land in Macao, the population had heard the sound of the Pátria II piercing through the rain. Beires and Pais made their way to a small Chinese town near the emergency landing site, about 800 m from the Hong Kong border, where no one spoke English. Continuing their walk in the pouring rain, they reached Hong Kong.

On 21 June, the Portuguese Navy gunboat Macau conducted an extensive search for the plane. It was feared the aircraft had crashed in the sea, but the gunboat was able to locate the stranded aviators. The plane was dismantled and placed aboard the navy boat, and on 25 June, Beires and Pais, accompanied by their disassembled aircraft, arrived in Macao.

Their extraordinary adventure covered a staggering distance of 16,760 kilometres in 117 hours and 41 minutes of flight time. But in an instant, Sarmento de Beires, Brito Pais and Manuel Gouveia solidified their places as pioneers, etching their names – and the name of Portugal – into the illustrious history of aviation.

Research by Jacinto de Jesus Tavares