In Wong Yu-fei’s family, every son learns the art of jook-sing noodle making at the age of 15. “This is when we are tall and strong enough to manage the bamboo pole,” he explains, describing the highly physical practice of straddling a thick bamboo stem to roll out noodle dough. Every daughter, Wong adds, learns how to make meat fillings for dumplings.

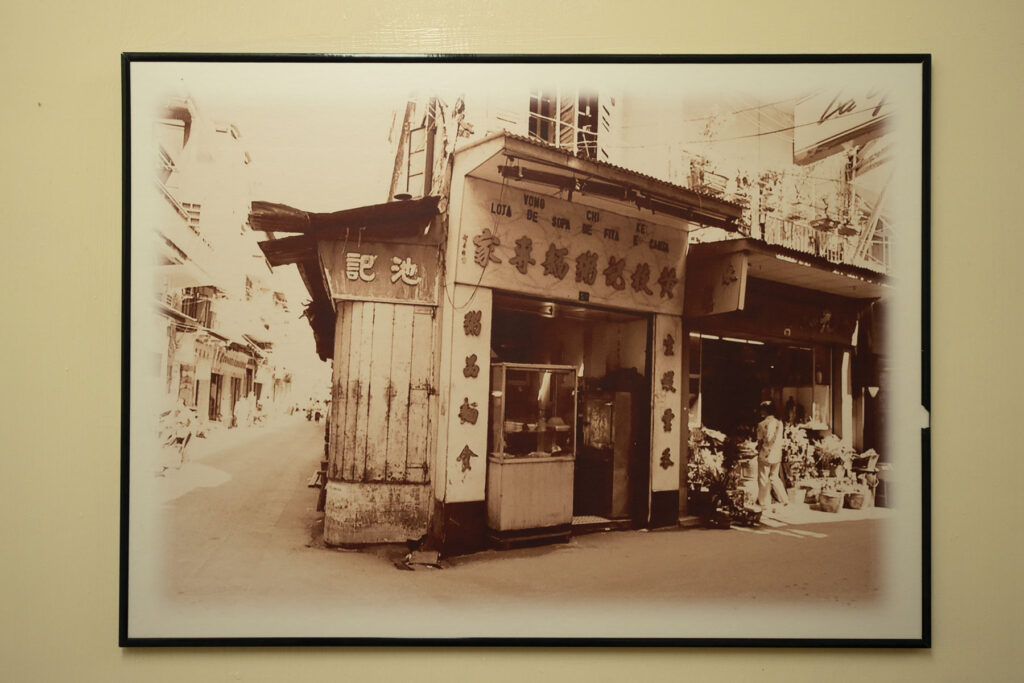

Wong, in his 30s, is part of the third generation to run Wong Chi Kei, a traditional jook-sing noodle company founded by Wong Woon-chi in 1946, in Dongguan, Guangdong Province. In 1959, what was then just a small eatery moved to Rua de Cinco de Outubro in the heart of Macao’s historic old town. Wong Chi Kei opened its second, far larger restaurant in 2000, in a three-storey building on Senado Square – one of the city’s tourism hotspots. A jook-sing noodle factory followed in 2006, testament to strong demand for the Wong family’s time-honoured skills.

You’ll find their high-quality, made in Macao products in local restaurants, Hong Kong supermarkets like City Super, and in a dedicated store at Hong Kong’s international airport. The business’s premium Yea Yea Noodles brand, featuring well-loved landmarks like A-Ma Temple and the Guia Lighthouse on its packaging, is even sold in dedicated vending machines at ferry terminals. Unlike the more generic noodle brands grabbed off shelves by home cooks, Yea Yea Noodles target people – often tourists – seeking a bona fide way to take Macao’s culinary heritage to home.

Traditional jook-sing noodle making is, in fact, a protected part of the city’s intangible cultural heritage. While named after the bamboo pole they’re flattened with, these noodles are also defined by two key ingredients: duck eggs and lye water, which impart a characteristic fragrance. This recipe and technique have been passed down from generation to generation by skilled artisans, though jook-sing noodles’ labour intensive nature means the tradition is struggling to stay afloat. The Wong family are one of just a few still “riding the pole” – as the dough rolling practice is known.

A family legacy in every bite

Wong grew up in Hong Kong, but visited Macao almost every weekend as a kid in the 1990s. He’d spend most of that time with his elderly grandparents – Wong Chi Kei’s founders – in their Rua de Cinco de Outubro restaurant.

“I remember there was a string between the two floors,” he recalls. “When we received a food order upstairs, we wrote it down on a piece of paper and attached it to the string with a peg. It would slide straight to the cashier.” Wong’s grandfather was in charge of preparing and cooking the jook-sing noodles, while his grandmother managed the cashier. Sadly, she died in 1996, a year before her husband, Wong Woon-chi, passed away.

The old restaurant contains many memories for the family. Wong, a cheeky child, remembers scribbling nonsense on bits of paper on the eatery’s upper floor, then sliding them down to his grandma. His cousin, Ken Li, who’s now in charge of producing Wong Chi Kei’s noodles, says he essentially grew up in the store. He recalls the steep learning curve experienced when his turn to master the bamboo pole came around. “It was tough as I had to manage everything by hand, including cutting and moulding each roll of noodles,” he says. The only way to guarantee jook-sing noodles’ bouncy, silken texture is to practice, practice, practice, Li emphasises.

Of course, the family business’ noodle-making operations have long outgrown that kitchen and a 900-square-metre factory in Macao’s Iao Hon District is Li’s current domain. While he still uses a bamboo pole to flatten the dough, other parts of the process – the rolling, folding, cutting and stretching – are handled by two large machines purchased from Japan. Li also has a large team of staff members to help him these days.

The factory produces between 500 and 1,000 rolls of jook-sing noodles every day, both plain and sprinkled with shrimp roe. It also churns out an array of condiments including bacalhau XO sauce, sakura shrimp sauce, chili sauce and dried crab roe. Half of the noodles are destined to be cooked immediately in the two Wong Chi Kei restaurants and other eateries around Macao. The other half gets dried, packaged up and sold as Yea Yea Noodles.

Even though Wong was involved in the business as a child, and watched his dad take it over from his grandfather, he hadn’t planned to follow in their footsteps. Instead, he studied business management and finance in the US. Wong drifted back into the fold after spending his early career in Hong Kong’s food and beverage industry. As his dad reached retirement age, the elder Wong wanted to spend more time writing than running a demanding business. So, in 2014, the younger Wong stepped in to take his place.

Noodles worth the wait

At the Senado Square eatery, Wong points out two large pieces of calligraphy written by his father to celebrate Wong Chi Kei’s 70th anniversary. “Next year, for our 80th anniversary, he may write another pair,” Wong notes. He also recalls the exciting day this restaurant opened, when he was just a kid. “There were crowds and lion dancing,” he says.

The crowds have remained: Wong Chi Kei’s Senado entrance often has a queue outside it. The eatery’s reputation for bouncy jook-sing noodles as well as heart-warming broths, shrimp roe and congee has travelled well beyond the Pearl River Delta, and tourists from countries including Thailand and South Korea seem more than willing to line up for the Wong family’s famous dishes.

The large restaurant’s old-timey ambience is another drawcard, with its dark panelling, traditional Chinese paintings and round wooden tables. The original, more compact Wong Chi Kei – a 15-minute walk away – is still running too, but has been renovated to have a more modern vibe, and serves a slightly different menu.

A grandfather’s dream

Macao residents always joke about the city’s close connections. Everyone seems to know a friend, colleague or relative of everyone else; “Macao is so small” is something you tend to hear a lot. Wong, now the face of his multi-generational family business, feels this interconnectedness strongly. It’s not unusual for someone to approach him out of the blue and say, “I eat your noodles all the time,” or, “I met your grandparents at the Rua de Cinco de Outubro restaurant.” Recently, a regular customer told Wong that five generations of his family had been frequenting Wong Chi Kei’s eateries.

These sentimental reminiscences helped convince Wong to launch the Yea Yea Noodles brand back in 2016. But he also wanted to turn one of his grandfather’s dreams into a reality. “When my grandpa was still alive, he dreamt of producing dried noodles,” the younger Wong says. He himself used to crave his family’s jook-sing noodles while studying in the US, so producing a more portable version of them seemed like an obvious way to expand the family business.

As for why he opted for the souvenir-style offering, Wong points out that noodles are celebrated for their prominent places in many countries and regions’ cultures. “From Italian spaghetti to Japanese ramen to the Shin Ramyun brand in South Korea,” he says. With this inspiration, he envisioned tourists viewing his family’s jook-sing noodles as more than just food. He wants them to feel like they’re buying a delicious piece of Macao’s rich culinary heritage, and something they could take home to a kitchen anywhere in the world.