Emperor Qianlong (1711–1799) wore many hats. He was a ruler who presided over one one of imperial China’s most prosperous eras. A devoted son deeply influenced by his family. And a husband whose poetry immortalised a beloved wife. His life was a blend of power and artistry, discipline and passion, military ambition and cultural refinement. From his formative years in the royal court’s residence for princes – which later became the Palace of Double Brilliance (Chonghua Gong in Chinese) – to his six-decade reign over a vast empire, Qianlong’s story continues to fascinate history buffs today. The Macao Museum of Art (MAM)’s current exhibition offers insights into the man behind the legend.

Titled “Palace of Double Brilliance”, this exhibition is the fruit of MAM’s annual collaboration with Beijing’s Palace Museum. It features more than 130 precious relics, each having touched the emperor’s life in some way. Qianlong followed in the footsteps of his father, Yongzheng (1678–1735), and grandfather, Kangxi (1654–1722), to rule China. His was the third in a series of prosperous reigns now hailed as the High Qing Era (1683–1799) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911).

The Palace of Double Brilliance, a royal residence within the Forbidden City, was the setting of many notable chapters throughout Qianlong’s life. At its namesake exhibition’s opening ceremony in late November, director of the Palace Museum Wang Xudong tells Macao magazine that the complex “contained many memories for the emperor”, particularly from his years of study as a young prince. “When you step into the palace today, you must consider how a prince became an emperor who ruled the country with so many ethnic groups in unity,” he says.

The residence was given the name ‘Double Brilliance’ by Qianlong’s loyal officials, in honour of a legendary leader of ancient China: Emperor Shun (c. 23rd century BCE), who succeeded Emperor Yao (c. 24th century BCE). The name reflects the continuation of wise and just leadership across generations. An apt moniker, given Qianlong’s own family’s achievements.

After ascending to the throne in 1735, Qianlong embarked on extensive renovations of the palace. He transformed it into a multifunctional complex boasting a gallery of treasures he’d received from his father as a prince; a theatre staging the opera shows he enjoyed with his mother; and a salubrious reception area where he entertained foreign envoys and hosted tea ceremonies.

In Qianlong’s later years, he wrote about the palace’s influence on his reign. “The governance of more than 40 years all came from this place,” he noted in his work titled, An Imperial Record of the Palace of Double Brilliance.

Royal attire

MAM’s exhibition is divided into four thematic sections. The first, Born to Be an Emperor, welcomes visitors with an installation recreating the Palace of Double Brilliance’s front chamber – complete with a plaque inscribed with Qianlong’s own calligraphy. The space is richly adorned with court furnishings, including incense burners, footrests and fans that offer a glimpse into the sumptuous tastes of the Qing court.

There’s also a striking copy of a portrait depicting young Qianlong in a yellow robe, painted by an anonymous Qing painter. Alongside the portrait, a similar robe is displayed in the flesh (or silk, as is the case here). The remarkably well-preserved garment has been embroidered with golden dragons, polychrome clouds and other imperial symbols. The physical presence of Qianlong’s regal costume, juxtaposed with the painting of the man himself, invites viewers to envision the emperor’s height and build, helping bridge the gap between historical imagery and lived reality. This kind of intimacy characterises the exhibition.

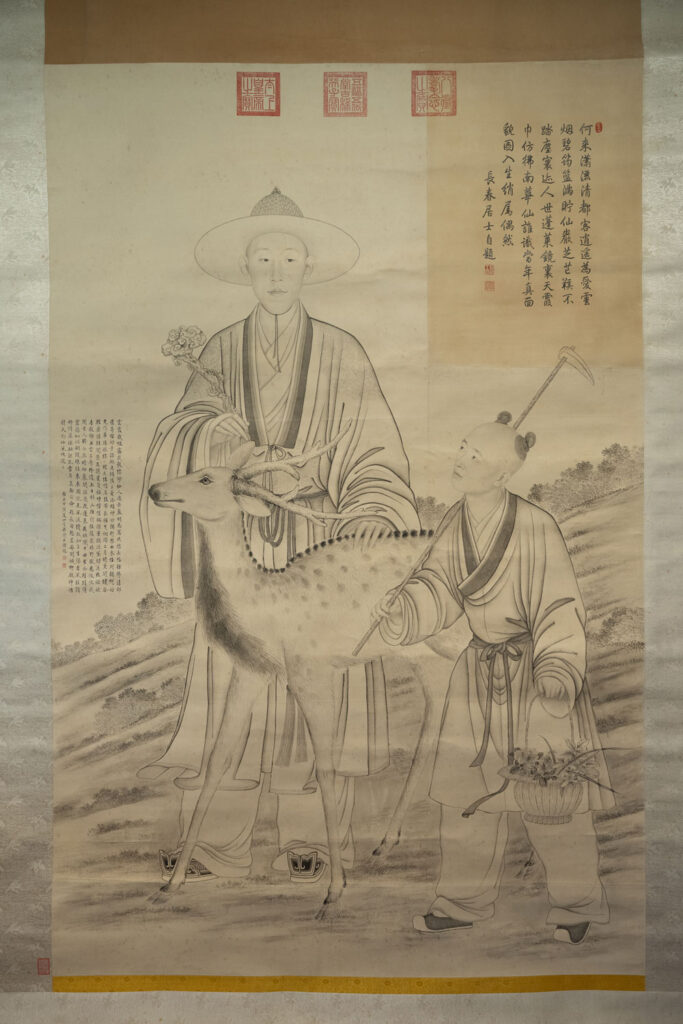

Another painting shows Qianlong in Han attire, stroking a sika deer with a child attendant standing by. Here, he resembles an immortal – a mythical being within Chinese folklore. Both the child and the deer were painted gazing up at the elegant prince, who had yet to ascend the throne. The inclusion of Han clothing, when Qianlong himself was Manchu, is considered emblematic of the leader’s future efforts to promote cultural harmony in his multi-ethnic empire. Portraying young Qianlong in this way foretold his reputation as a sovereign who valued and embraced the differing cultural customs existing in his country.

Two beloved empresses

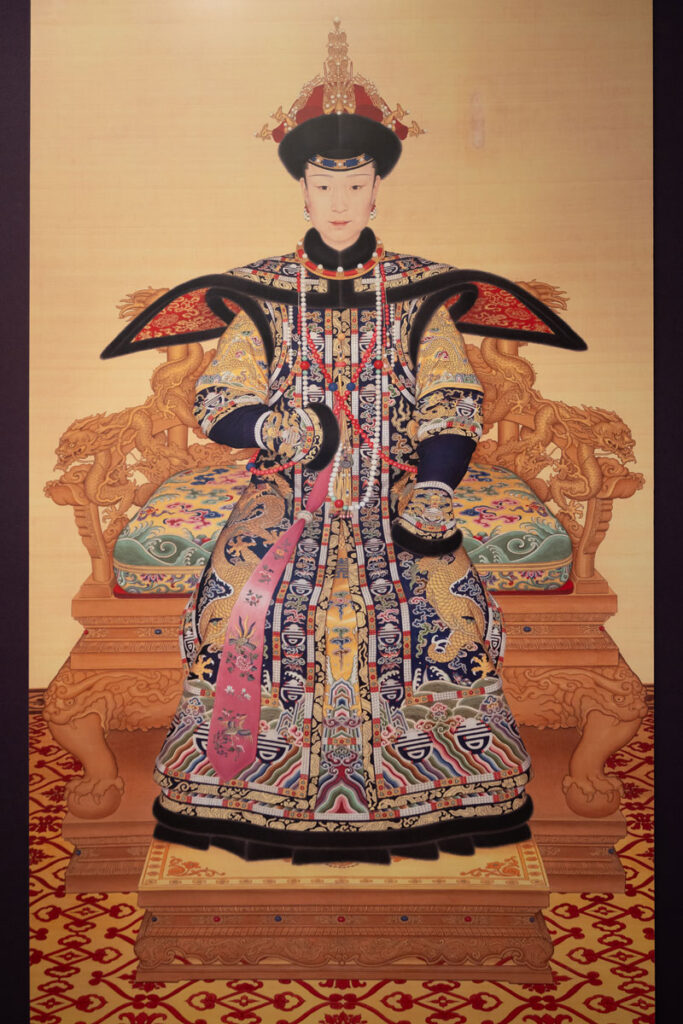

The exhibition’s second section, Marriage and Family, delves deeper into the emperor’s connections with his first wife as well as his mother. In 1727, at the tender age of 15, Qianlong married a woman from the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner Fuca clan, who became known as Empress Xiaoxianchun (1712–1748). Renowned for her prudence and sensibility, the empress was selected by Qianlong’s father, Emperor Yongzheng, to be the primary escort for his son.

One of MAM’s exhibits is a plaque inscribed with the words ‘Zhilan Shi’, or ‘Orchid Chamber’ – the name of Xiaoxianchun’s personal residence within the palace. Qianlong chose the moniker as a mark of deep affection for his wife, drawing from an old Chinese saying: “When one lives with virtuous people, it is as if one has entered a room filled with the fragrance of orchids.”

The couple’s devotion to one another has been widely documented by Qianlong himself; a substantial number of the more than 40,000 poems he wrote throughout his lifetime were dedicated to his first wife. In 1748, during an imperial tour of the country’s east, the empress fell ill and died. To mourn her tragic passing, Qianlong wrote a moving eulogy comprising four poems. These are displayed on their original scroll in the “Palace of Double Brilliance” exhibition.

Followers of Chinese costume dramas will have heard of the emperor’s mother, Empress Dowager Chongqing (1692–1777), also known as Empress Xiaoshengxian. The 2011 TV series, Empresses in the Palace, offers a heavily fictionalised account of her life. Quite different interpretations of Xiaoshengxian’s character were portrayed in its 2018 sequel, Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace, and in another drama series from that same year, Story of Yanxi Palace.

MAM’s exhibition pays tribute to the empress’ enthusiasm for Chinese opera through displays of costumes worn by court performers. There’s also a selection of bound scripts outlining performance synopses from special events staged during the likes of Lunar New Year and the Double Ninth Festival. Their stories tend to be fables full of auspicious meanings.

The two empresses’ lives are further illustrated through personal artifacts, including kingfisher feather hair pins shaped like chrysanthemums and butterflies; delicate symbols of the women’s grace and elegance.

Literary and military prowess

Qianlong, who received Manchu and Confucian education from childhood, dedicated his reign to promoting cultural integration. This is documented in the third section of the exhibition, the Flourishing Era of Civilian Rule. Here, visitors can peruse a selection of his written compilations, including Siku Quanshu (Complete Library of the Four Branches of Literature), Lulu Zhengyi Houbian (The Continued Revision of the Imperial Music Treatise) and Yuelu Quanshu (Collection of Texts on Music). Each book demonstrates the emperor’s commitment to preserving and synthesising diverse cultural and intellectual traditions, showcasing his ambition to position himself as a learned and enlightened ruler.

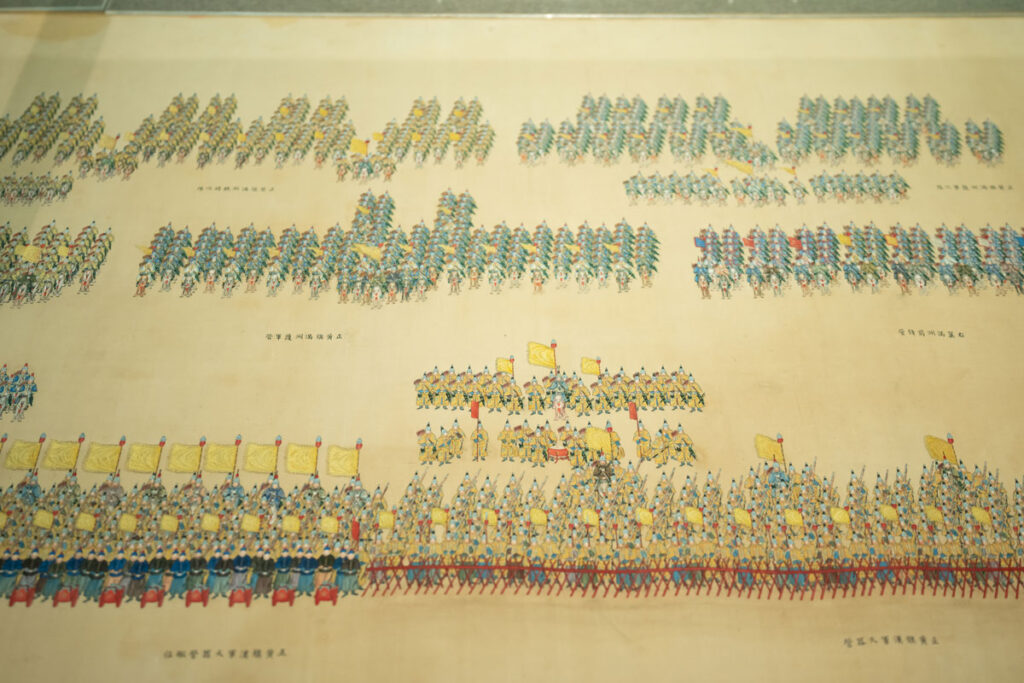

Emperor Qianlong was a cultured man, but also a formidable military leader. He proudly referred to himself as the ‘Old Man of Ten Great Campaigns’, a title reflecting the significant military expeditions he led between 1747 and 1792. This martial legacy is highlighted in the exhibition’s final section, Efficient Governance and Harmonious Nation. Featured here are artworks that vividly portray his victories, such as the Yili Region campaign and the pacification of the Dzungars. A scroll stretching almost 2 metres in length, depicting Eight Banners forces on parade, is one highlight here. Titled Emperor Qianlong’s Review of the Grand Parade of Troops, the scroll is considered a valuable historical document that sheds light on costumes and ceremonial practices of the era. The Eight Banners were a multi-ethnic military organisation incorporating Manchu, Han and Mongol forces during the Qing dynasty.

A quarter century of collaboration

MAM and the Palace Museum curated the “Palace of Double Brilliance” exhibition to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Macao’s return to China, which took place in December. The exhibition also marked a quarter century of collaboration between the two great institutions.

Staging an ambitious show like this here, in Macao, holds special significance, according to the Palace Museum’s director. Wang believes that the Special Administrative Region’s reputation as a hub for cultural exchange will enable Emperor Qianlong’s story – and through it, China’s history – to reach a broader audience, he shares with Macao magazine.

“The openness and inclusiveness of Chinese culture further allows for cultural exchange through a place like Macao, where it can absorb some of the outstanding achievements of other civilisations,” he says. “At the same time, it enables other cultures worldwide to understand Chinese culture through this unique location.”