In 2004, Lilian Chan and a team of researchers from the Macao Museum embarked on a journey to explore the life of Zheng Guanying (1842-1921), the successful entrepreneur and one of China’s most significant reformist thinkers. Their first port of call was the Macao home of Cheng Chang Pong, one of Zheng’s descendants, where he shared an old family photo taken at the Mandarin’s House and the prominent family’s genealogy book. Both items were later donated to the Macao Special Administrative Region (SAR) Government.

The photo depicted a large family in front of a shed that still stands at the Mandarin’s House, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Macao’s historic centre. Zheng, who is known as Cheng Koon Ying in Cantonese pinyin, is to the right, staring into the camera. The photo is now on display in a permanent exhibition about his life, at the same sprawling residence in which it was taken. This was also where Zheng wrote his masterpiece, Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age, which went on to influence great Chinese leaders like Mao Zedong and Sun Yat-Sen after being published in the mid-1890s.

It was Cheng’s genealogy book that excited Chan most, however. “It felt so strange and marvellous to read,” she tells Macao magazine. “In the book, we discovered Zheng’s given name was originally Zhangying [Cheong Ying in Cantonese], not Guanying [Koon Ying in Cantonese]. Nobody knew about it.”

With the help of donations, the team deepened their research. They travelled to Zheng’s birthplace, Xiangshan (now Zhongshan), and to Shanghai, where Zheng spent much of his life after being sent there to work with an uncle at the age of 16. During the researchers’ journey, they forged close partnerships with institutions like the Shanghai Library and the Shanghai Audio-visual Archives. They also connected with more of Zheng’s descendants, both in Macao and abroad.

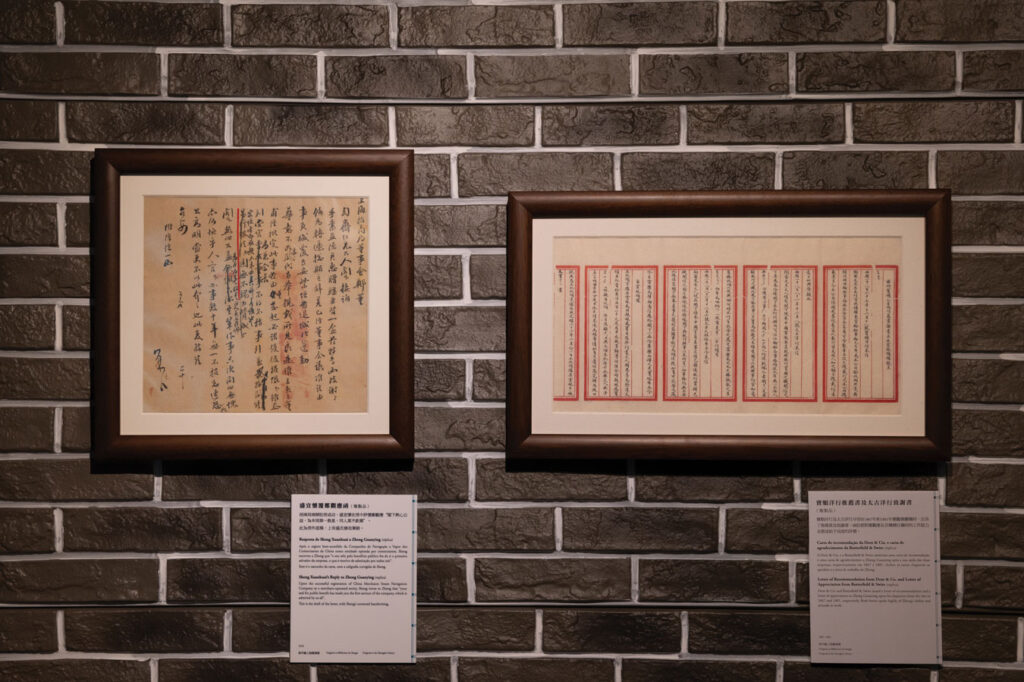

In September of this year, the team’s two decades of research culminated in the “Exhibition of the Legacy of Zheng Guanying” at the Zheng Guanying Memorial Museum, located within the Mandarin’s House. The three-storey museum displays over 100 items in its Zheng exhibition, including writings, documents, letters, photographs, plaques and couplets. These reveal important insights into Zheng’s far-reaching influence on commerce, governance and social reform. The exhibition, which was inaugurated in late September, is being displayed permanently at Zheng’s namesake museum.

The soul of a mansion

The earliest iteration of the Mandarin’s House was built in 1869, by Zheng’s father, on the Macao Peninsula’s Travessa de António da Silva. The compound underwent many extensions and alterations over the following decades, transforming it into a multigenerational mansion. The structure was primarily built in a Lingnan style typical of southern China, but also features subtle Western influences.

The Macao SAR Government acquired the Mandarin’s House in 2001, after the remaining family members and tenants had moved out. It then embarked on a painstaking restoration scheme with the aim of returning the run-down complex to its former glory. In 2005, UNESCO deemed the Mandarin’s House worthy of World Heritage status. In 2010, it was finally ready to open its doors to the public. The compound’s walled gardens and courtyards, elaborate interior frescoes, shrine to an earth god and exquisitely carved screen doors can now be explored by anyone seeking a serene escape from the city’s bustle.

While the Mandarin’s House is important architecturally, the people who lived there – like Zheng – add much to its intrigue. As Chan puts it, a building’s inhabitants lend it its “soul”. She and her team have staged three exhibitions about Zheng to date, though the current one is the most comprehensive. The fact it is being held inside the thinker’s own home makes this exhibition especially impactful. “The mansion is like a body,” she says. “But what’s most important is its soul. That’s why we want to reveal what Zheng achieved in history, and how he influenced the world. We want to show the mansion’s soul to our audience.”

An inspiration to the greats

The first part of the exhibition concerns Zheng’s connections to three historical figures profoundly influenced by his book, Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age: Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), Emperor Guangxu (1871-1908) and Mao Zedong (1893-1976).

Sun Yat-sen, the revolutionary leader who overthrew the Qing dynasty, drew inspiration from Zheng’s ideas on reform and modernisation. Emperor Guangxu was so impressed by the book that he ordered 2,000 copies to be distributed among his ministers. Mao, meanwhile, credited Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age with shaping his policies on industrialisation.

The first exhibit in this section is a replica of a letter Zheng wrote to the Chinese politician Sheng Xuanhuai in 1894. In it, he expressed his hope that Sheng would recommend Sun Yat-sen, then a young revolutionary, to Qing Viceroy Li Hongzhang – an advocate for modernisation and a key figure in China’s Self-Strengthening Movement. Zheng was trying to help Sun secure a passport so he could travel overseas. History tells us that while Sun did get his passport, he didn’t manage to meet Li. He did, however, write a lengthy petition to the viceroy presenting his own ideas for China’s modernisation. Zheng’s original letter from this period is housed in the Shanghai Library.

Visitors can also view the replica of a note written by Mao Zedong to his cousin, Wen Yunchang, in 1915. The man who would go on to found the People’s Republic of China was a student at the time, and mentions Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age to his cousin. In a later autobiography, Mao acknowledged Zheng’s writing had a profound influence on him.

A man of commerce and adventure

On the second floor, visitors learn about Zheng’s spectacular career in commerce. As a teenager in Shanghai, Zheng picked up English and enrolled in evening classes at the Anglo-Chinese School. After just one year in the city, he began working for Butterfield & Swire (now Swire Group), a major British trading firm with offices in Shanghai. He eventually established branches of the company – which specialised in Chinese tea and silk at the time – in Jiangxi and Fujian provinces, and was an early investor in the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company, established by the Qing government to challenge the foreign firms dominating China’s import and export business. Founded in 1872, the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company still operates today as the state-owned enterprise China Merchants Group.

In 1880, Zheng was appointed to manage the Shanghai Machinery and Weaving Bureau along with the Shanghai Telegraph Bureau. Parts of the exhibition are dedicated to showcasing Zheng’s leadership roles and achievements across these entities, as well as with the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company.

The exhibition offers interactive activities, too. There’s a machine where children can learn how to send a telegraph using Morse code, as well as a digitised map letting visitors to trace Zheng’s travels across China, as they are recorded in his Yangtze River Diary. The book chronicles a lengthy trip from Shanghai to Chongqing along the Yangtze River, during which Zheng examined his multifaceted business interests.

A legacy of benevolence

Also featured in the exhibition is a large plaque featuring the characters “崇德厚施”, or “Promote Virtue and Practice Generosity” in English. The plaque was a gift from Zeng Guoquan, a provincial governor of Shanxi Province whom Zheng helped out during the devastating drought of the late 1870s – using his influence to encourage individuals and organisations to donate to disaster relief. “Zheng helped Zeng manage the crisis and appease the public,” Chan explains.

In his later life, Zheng devoted himself to education. He was chairman of a public school founded by the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company in Shanghai and honorary director of the Shanghai Commercial Middle School.

Retirement and writing

When Zheng took a step back from his commercial positions in the mid-1880s, he returned to Macao to live in the home his father had built: the Mandarin’s House. The change in pace allowed him to concentrate on further developing his reformist ideas, and to write.

In Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age, Zheng reflects on his experiences as both a businessman and an observer of the declining Qing dynasty, which was confronted by aggressive foreign powers. The book managed to capture the zeitgeist, putting forth bold recommendations on how to reform China’s leadership, education, infrastructure and medical systems.

Zheng didn’t spend the rest of his life in Macao (in fact, he died in Shanghai), but a number of his family members remained in the Mandarin’s House for decades after he had gone. The exhibition includes a hand-drawn floorpan from the 1950s that shows how the space was divided to accommodate its many occupants, which included non-family member tenants.

Now that the compound has been restored to its original splendour, visitors are able to step into the world of Zheng Guanying. Through its permanent exhibition, thanks to the hard work of Chan’s team of researchers, they will also gain a unique sense of the remarkable man’s legacy.