An unexpected life unraveled for Cheung Po Tsai as he rose through the ranks of piracy only for a twist of fate to have him become a successful pirate catcher for the Qing Navy.

His story is the stuff of legends: a random boy kidnapped by pirates only to rise up the ranks to command a massive fleet alongside his lover, and when all seemed lost, securing his spoils and a position of power in the same government he tormented for years as a pirate.

Cheung Po Tsai – literally Cheung Po the Kid, like many an outlaw before and after him – packed a lot into his short life: 15 years as a commoner, 12 years as a pirate, and 12 years as a pirate catcher in the Qing navy. Traces of the 19th century pirate can still be found today, in the landscape of Hong Kong and in the stories told on screens big and small.

An unlikely beginning

Born in 1783 in the Xinhui district of Jiangmen, Cheung came from humble beginnings as the son of a fisherman.

That all changed when, at the age of 15, he was abducted by a powerful local pirate named Cheng I. Forced to join Cheng’s fleet, the young Cheung soon impressed the pirate and began to rise up through the ranks. He became heir to Cheng I after the pirate and his wife adopted him as their stepson.

When Cheng died in Vietnam on 16 November 1807, Cheung was the obvious successor. His widow, Ching Shih, while formidable could not command the Red Flag Fleet herself. But her cleverness ensured that she and Cheung retained the loyalty of Cheng’s relatives who led other pirate vessels, effectively stifling any threats to their power.

The two soon became lovers, sharing control of the new fleet: Ching Shih handled business affairs while Cheung was responsible for the military side of the operation, with Cai Qian serving as a loyal lieutenant. His wife,

a weapons expert who spoke fluent English, had enabled the pirates to acquire weapons from Western arms dealers.

Based on outlying islands in the South China Sea, the Red Flag Fleet was one of several pirate groups that made their living targeting the Pearl River Delta, then (and now) the most prosperous region of China. They exploited the decline of the Qing dynasty, its navy unable to effectively protect the commercial vessels and ports in the Delta.

Delta residents were forced to pay ‘protection’ money to the fleet, while merchant vessels wanting to pass through the area paid a tax. Not satisfied with these schemes, Cheung and Ching Shih expanded into blackmail and extortion, developing an extensive spy network in the mainland.

Ching Shih used the profits from their various ventures to create a supply chain, contracting with farmers to supply them with food, and built the fleet to a point that surpassed many navies. At its peak, they numbered an estimated 1,800 vessels and 80,000 followers, operating along the coast of the South China Sea and as far south as Malaysia.

Like many pirates, Cheung and Ching Shih operated under a complicated code of ethics. While Cheung sometimes gave food and money to the poor, making him something of a Robin Hood figure in their eyes, he also oversaw horrific violence. Raided towns were subjected to rape and murder, and female prisoners were often sold to the crew as ‘wives.’

Their massive crew faced similarly harsh punishments for most infractions, with death sentences issued for everything from stealing loot to going ashore without permission. The pair ruled with an iron fist, and for years it served them beautifully, adding to their numbers – and their treasure.

Then the fleet suffered a heavy blow in 1809. When the Qing navy discovered that Cai Qian had docked in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province, they blockaded him inside the port. The Qing were not about to waste an opportunity to retaliate against the pirates who had harried their waters for so many years. Cai likely died during the attack when canon fire sunk his ship, although the more colourful stories claim he committed suicide – a single shot to the head with a golden bullet.

As much as they frustrated the Qing government, the Red Flag Fleet had left European vessels alone. But the temptation became too great, and in early September 1809, the pirates seized a Portuguese trading ship travelling from Timor to Macao, both Portuguese colonies at that time. They killed the entire crew before making off with their loot.

Battle of the Tiger’s Mouth

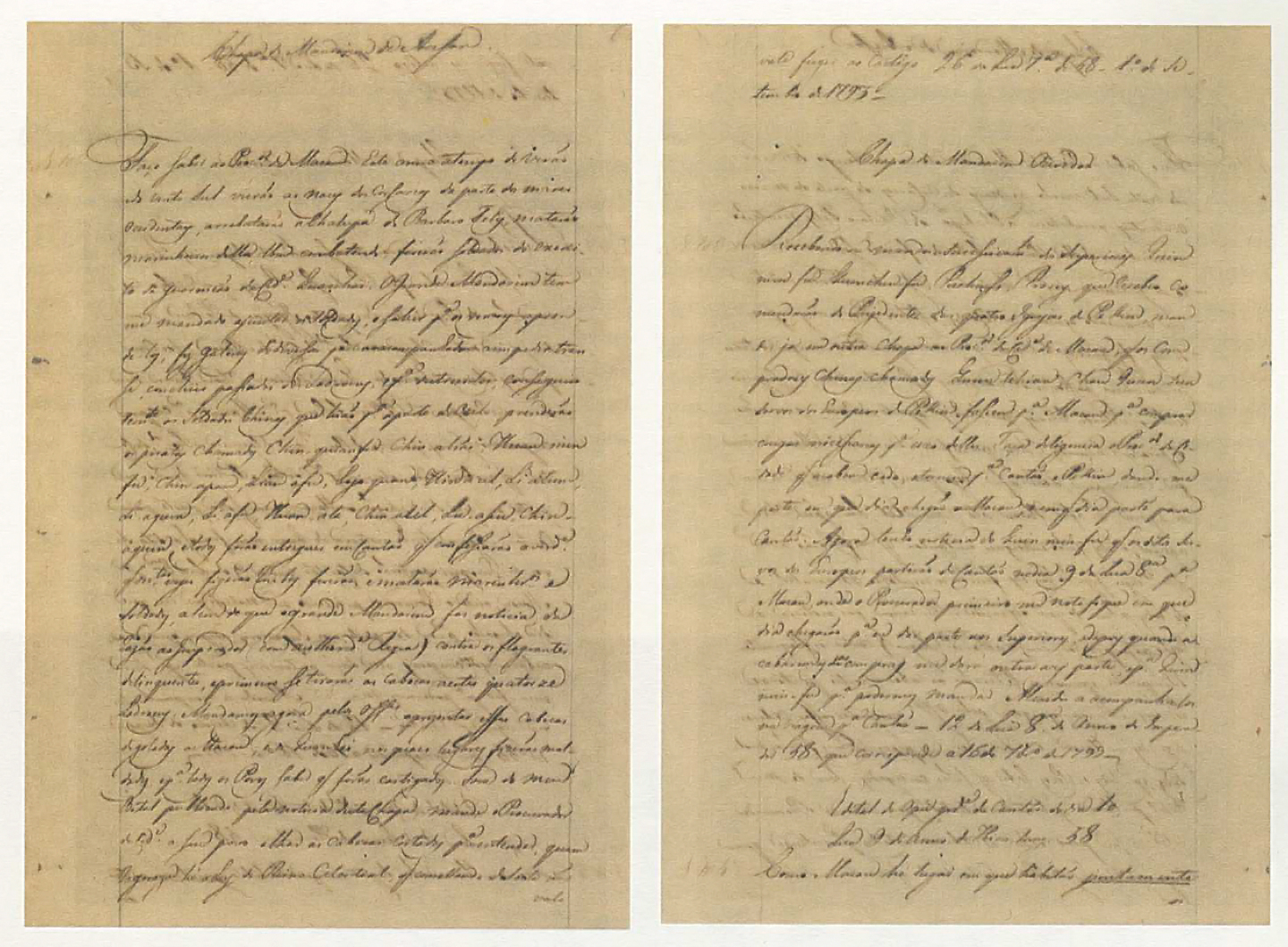

In response to the massacre, the Leal Senado ordered Captain José Pinto Alcoforado e Sousa to lead three armed vessels to attack the Red Flag Fleet. At the governor’s request, a British fleet anchored in Macao agreed to join the attack.

The first battle took place on 15 September 1809. The Portuguese vessels confronted the far larger contingent of the Red Flag Fleet, numbering 200 ships, in the Humen Strait of the Pearl River. The promised assistance from the British fleet never came, yet with 39 artillery pieces, the Portuguese managed to win the day, forcing the pirate ships to scatter.

While not a total victory, the outsized showing by the Portuguese caught the attention of the Qing government. Emissaries arrived in Macao on 23 November, proposing a joint operation against the Red Flag Fleet comprised of 6 Portuguese and 60 Chinese vessels.

The governor of Macao agreed, ordering the formation of a larger fleet, and in less than a week the six Portuguese ships set off from Macao to join the Qing fleet. Within hours of leaving, however, the Portuguese flotilla was intercepted by the Red Flag Fleet. With 120 artillery pieces and 760 men, roughly three times what they had in the September clash, the Portuguese once again came out on top. After some nine hours of fighting, they had sunk 15 pirate ships and badly damaged several others. The Red Flag Fleet fled, regrouped, and attacked again only to incur more losses.

With aid from the much larger Qing fleet not forthcoming, the Portuguese decided not to push their luck and returned to Macao rather than pursue the pirates.

On 11 December, Cheung launched an attack against the Portuguese flotilla, striking closer to Macao than any previous clash. His attempt to bring a decisive end to the battle failed utterly. Not only did he lose a further 15 ships, his failed attempt at negotiating a peace deal with Alcoforado cost him a valuable ally, the Black Flag Fleet. With those pirates now firmly on the government’s side, Cheung’s supporters began to lose confidence in their commander and the likelihood of success. Many deserted.

Clashes in early January inflicted further losses on the dwindling Red Flag Fleet before the final and decisive battle on 21 January 1810. Cheung threw every resource available – over 300 ships, 1,500 guns and 20,000 men – against the Portuguese flotilla, anchored near Lantau Island. It backfired horribly: the massive number of pirate vessels struggled to manoeuvre around each other, offering up a slow, heavily clustered target for the superior Portuguese artillery.

When Alcoforado spotted an extremely large junk, transformed into a floating pagoda, at the centre of the pirate fleet, he ordered artillery to fire on it until the badly damaged vessel sank beneath the waves. Seeing that, the pirates retreated into the shallow Hiang San River where they were trapped by a Portuguese blockade.

Known collectively as the Battle of the Tiger’s Mouth – taken from the Portuguese name for the strait, Boca do Tigre – these clashes brought Cheung’s short but successful career in piracy to a close.

After holding out for two weeks under blockade, Cheung sent a request to the Portuguese commander for an emissary to negotiate the pirates’ surrender. Alcoforado chose instead to go himself, taking a small vessel to meet Cheung aboard his flagship. Impressed and flattered by his bravery, Cheung abandoned his original plan – using negotiations to buy time – and immediately capitulated to the Qing authorities.

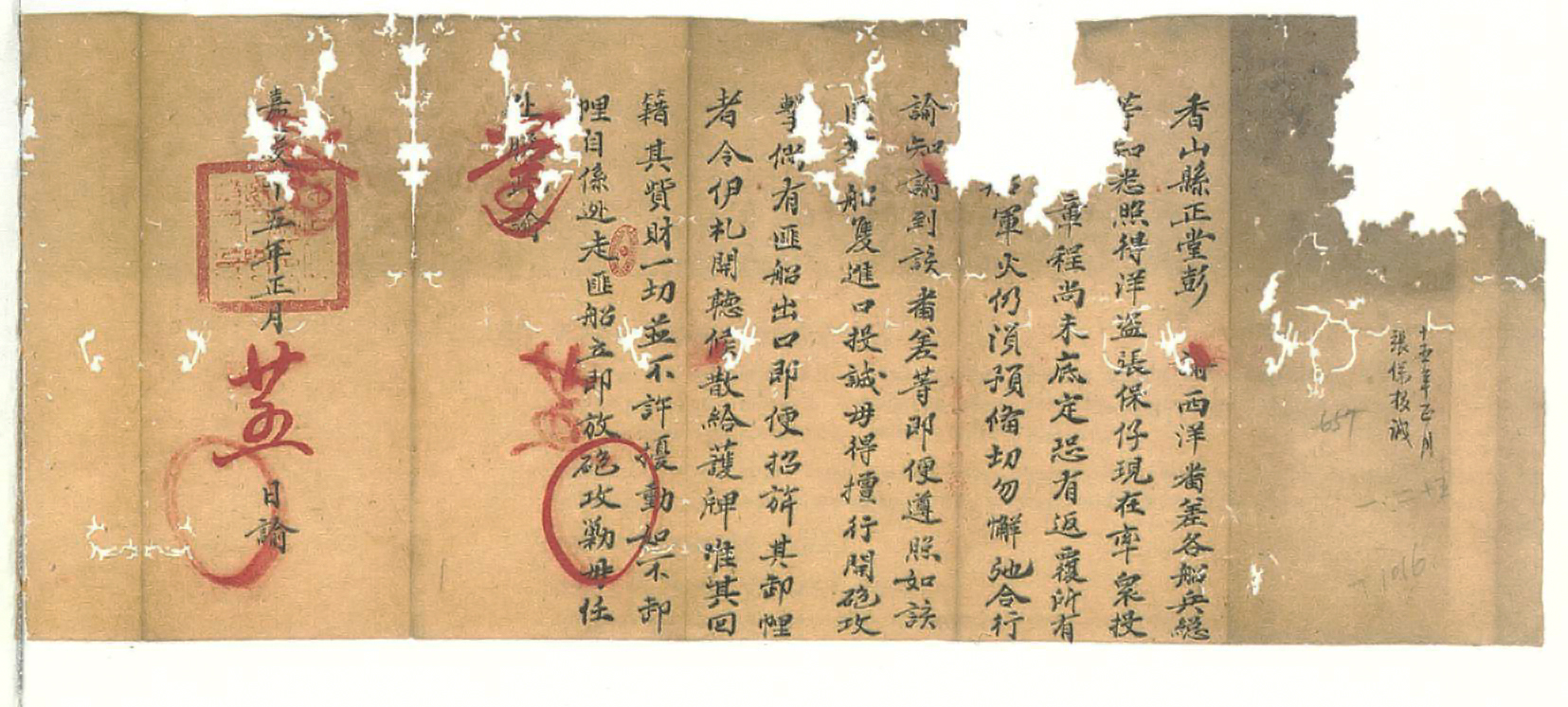

On 21 February, the pirates signed a peace treaty under which they agreed to submit to the Qing emperor and Cheung, to become an officer in its navy with the mission of fighting pirates. He and his lover bargained well: less than 400 of their men were punished and only 126 executed, a tiny fraction of those under their command at the time. The rest were allowed to keep their booty, and most were offered jobs in the Qing military.

Two months later, on 20 April 1810, Cheung formally handed over his fleet and weapons: 280 ships, 2,000 guns, and more than 25,000 men. Zhang Bailing, governor of Guangdong province, accepted his surrender and to the surprise of everyone, the Portuguese navy made no claim on the booty – greatly impressing the Qing officers.

Cheung became a colonel in the Qing navy and was assigned to the Penghu Islands, an archipelago in the Taiwan Strait. The Qing gave him command of 30 ships and allowed him to retain 30 of his own as a private fleet. He spent the rest of his life fighting pirates, helping the Qing to cripple piracy in the region by the 1820s.

Cheung and Ching Shih were married, their nuptials witnessed by the same Governor Zhang who had overseen the pirate’s surrender earlier in the year. In 1813, she gave birth to their first child, a boy named Cheung Yu Lin, and later, a daughter.

During his naval career, Cheung made several formal visits to the Leal Senado where he met several of the Portuguese officers who took part in the Battle of the Tiger’s Mouth. Among them Gonçalves Carocha, a Macanese pilot whose ship provided critical supplies and nimbly avoided capture while inflicting damage on the pirates.

Cheung earned a promotion following the successful capture of the wanted pirate Qu Shi Er. In 1819, Cheung was appointed deputy general in Fujian, where he served until his death in 1822.

On 20 April 1810, Cheung formally handed over his fleet and weapons: 280 ships, 2,000 guns, and more than 25,000 men.

Dead at 39 years old, Cheung had served 12 years with the Qing navy – the same amount of time he spent as a pirate after being kidnapped as a teenager. Now twice widowed, Ching Shih moved to Macao where she opened a gambling house and a brothel. She died peacefully in 1844, a grandmother of 69 years old; her descendants still live in the city today.

Lasting legacy

While his blood may be in Macao, it is Hong Kong that still bears the influence of Cheung Po Tsai. He built several temples to the deity Tin Hau, goddess of seafarers, in Stanley, Ma Wan, and Cheung Chau – which is also home to Cheung Po Tsai Cave, a small, natural cave said to be where Cheung stored his loot during one episode in the fateful Battle of the Tiger’s Mouth.

Perhaps it is this historical connection that makes the site such a popular attraction for trekkers and treasure hunters today – after all, Cheung utilised many caves throughout the outlying islands of Hong Kong during his time as a pirate. Visitors to the Cheung Chau site enter via a ladder, descending 10 metres to a path that extends another 90 metres before reaching the exit. The space is so narrow visitors can only move one by one, with nothing but their own flashlights to illuminate the darkness.

Cheung Po Tsai left his mark on popular culture as well, his thrilling life story inspiring many Hong Kong films, including the 1973 film The Pirate, as well as television dramas like the 2015 series Captain of Destiny. He even inspired a character, Sao Feng (played by Hong Kong actor Chow Yun Fat), in the Hollywood blockbuster Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End.