“When these ambassadors go to the king, they do not see anything but the vague shape of his body behind a curtain, and he answers from there, and seven scribes write down the words as he says them; the mandarin officials sign this without the king’s touching it, nor being seen, and they return; and if they take a present of a thousand, he presents them with double.”

This is just one insight from the landmark 16th-century book Suma Oriental by Tomé Pires, which impressively details the embassies of the kings of Java, Siam, Malacca and others, every five years to Beijing, with “the best there is in his country of what he knows they like there.” From Malacca, for example, the Chinese emperor received pepper and white sandal-wood, aloes, birds, rings with precious stones, and many other gifts.

“These ambassadors,” he noted, “can enter and leave China.” That was not Pires’ experience, himself an ambassador for King Manuel I at the beginning of Portugal’s ‘golden age of discovery’ in the Indian Ocean. He would never return to his homeland, and his fate is still the subject of much controversy among historians. Pires’ embassy accomplished nothing at the time, yet it arguably helped pave the way for 500 years of peaceful relations between China and Portugal, mainly through Macao.

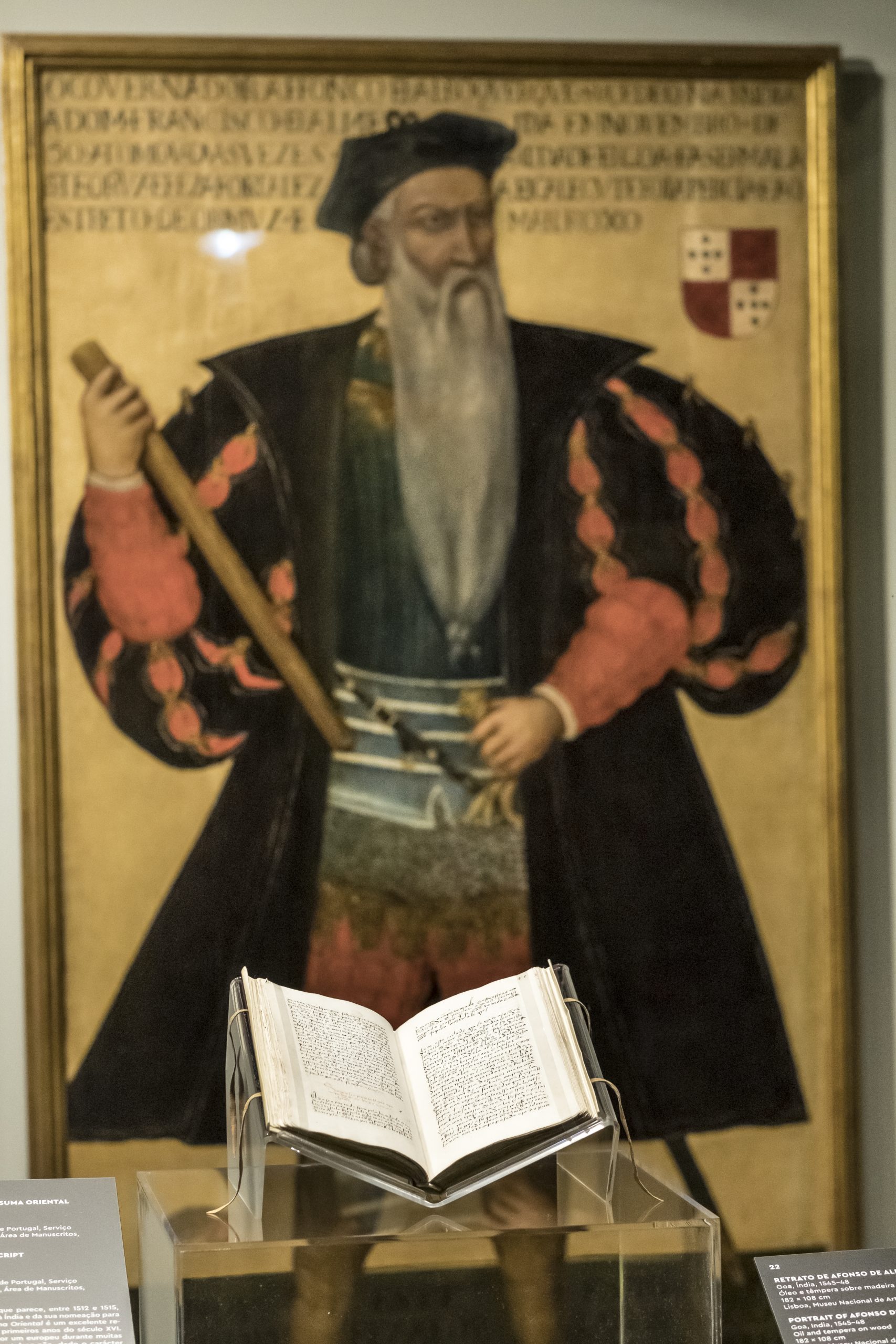

Pires, along with two other Portuguese diplomats who helped lay the foundation for European and Chinese links, features in the “Three European Embassies to China,” on display at Museu do Oriente in Lisbon until 21 April. The exhibition curator, Prof Jorge dos Santos Alves, rejects the traditional interpretation stating that Pires’ 1517 embassy, which disbanded before even reaching the Chinese emperor, was a failure. In fact, he contends, the inroads and the knowledge gained proved highly relevant in subsequent stages. “It was phase one of a learning process,” Santos Alves told Macao Magazine in Lisbon.

With this embassy, “the Portuguese entered the radar of Chinese diplomacy. For the first time, there is an approach. But most of all, the following embassies no longer made the same mistakes.”

Due to its seminal nature, Pires’ embassy had many flaws. To begin with, the Portuguese were not even known to the Chinese Empire, who termed them ‘franks’ based on Asian contacts with crusaders fighting under Charlemagne, King of the Franks. Rather than referring to the specific Germanic tribe, China applied it to Western Europeans in general.

Pires arrived in Canton in 1517 only to discover that, as the representative of an unknown kingdom, he was barred from travelling north to the emperor. The embassy faced many setbacks while it lobbied for admission, including the arrival in Canton of a Portuguese armada under Simão de Andrade. Then, precisely as Pires was struggling to obtain passage, the emperor died and all trade was suspended.

Even the terminology used for the Chinese emperor in the letter signed by Portuguese King Manuel I – “my brother” – caused problems: “The letter arrived translated in terms that were not acceptable. The Chinese emperor did not acknowledge ‘brothers,’ much less among ‘barbarians’ whose origins were unknown,” Santos Alves explained.

To avoid such missteps going forward, Pires began writing a book in Malacca based on interviews, research, and translations of Asian texts. The Suma Oriental offered a depth of knowledge previously unseen in the Western world, revealing to the King of Portugal many of the secrets of Asia, the world’s richest region at the time.

“It’s a survival kit, a guide to Asia – it’s politics, diplomacy, military issues, religions, finance, anthropology, sociology… everything is there. It was the first major European description of Asia.” Much of the information is sensitive, what later became known as intelligence, so the book was handled with care by the Portuguese Court. In fact, only two manuscript copies of it are known: one in the Portuguese National Library, abridged; and another, in the library of the French National Assembly, complete.

A complete version wasn’t printed until 1948, finally recovering Suma Oriental as a resource for historians. This year, Lisbon’s Fundação Oriente is set to publish the first complete annotated version in English.

Key to Pires’ efforts were the overseas Chinese, from second or third-generation Chinese families who had spread across Southeast Asia. Mainly comprised of traders and merchants, these men served as interpreters to the Portuguese in Malacca as well as information sources and emissaries to kingdoms in the region. Some of them operated legal trade routes, others did not. This decision by the Portuguese to establish links with smugglers led to clashes, even sea battles, with China, Santos Alves explained.

Malacca was, at the time of Pires’ arrival, a key trading outpost between India and China. The exhibition attempts to illustrate the diversity of people, ideas, and goods that circulated in the port, including original 16th-century Chinese porcelain from private collections and from Portugal’s Museum do Oriente. His original mission in the new colony was to buy pharmaceutical goods for the court, but the apothecary was later entrusted with accounting at the Malacca outpost, evidenced by a 1512 original account book bearing his signature. In Santos Alves’ words, Pires was a “one-man band.”

Such historic documents are presented alongside objects that help illustrate the richness of the region. These include spices like turmeric and ginger, which were also used as medicine at the time,

as well as the mythical bezoar stone, a Central Asian product used as an infusion against fevers which was highly coveted in Asia.

On a more contemporary note, visitors can observe a 20th-century painting of Tomé Pires by acclaimed painter Júlio Resende, among other artistic works. It includes a sign for the street bearing Pires’ name, which in Macao, ends where the street named for Fernão Mendes Pinto begins. Although Mendes Pinto is credited with issuing “Macao’s birth certificate” in his letters, according to Santos Alves, Pires “opened the door to establishing the Portuguese in Macao.”

Pires began “the modern age diplomatic relations by the Portuguese in China,” he asserted.

The judge who impressed an Emperor

The “Three European Embassies to China” exhibition takes visitors through a combination of historical facts and documents with 70 pieces, including religious art and other valuables. One highlight: a rarely shown letter from Emperor Qianlong to Portuguese King Joseph I, dated 1753. The four-metre yellow silk letter, purportedly sealed by the emperor himself, is considered one of a kind. Richly decorated with dragons and red Chinese and Manchu stamps, it contains Chinese, Manchu, and Portuguese writing. Jesuit priests working for the Chinese Court assisted in the translation, as well as the difficult diplomatic and ceremonial arrangements for the emperor’s audiences with the ambassador.

Qianlong’s letter represented the culmination of a highly successful embassy by Francisco Pacheco de Sampaio, a country judge whose appointment remains difficult to explain today, according to curator Jorge dos Santos Alves.

This “absolutely remarkable man” prepared extensively for his mission, reading “everything there was to read about China” from the royal libraries, researching and interviewing experts. As a result, it was the best-prepared embassy – and the best documented; even a detailed expense account remains, complete with the price of all the items sent to the Chinese emperor as gifts.

An emerging military power in the Indian Ocean at the time of Tomé Pires’ embassy, Portugal’s political, diplomatic, and military power had faded by the time Pacheco de Sampaio travelled to Beijing. In fact, tightening the country’s grip on its Asian colonies was part of his mission.

In spite of this decline – or perhaps because of it – along with the emergence of other European powers in Southeast Asia, like Great Britain and France, Pacheco de Sampaio appears to have made a mark on Emperor Qianlong. He received the Portuguese ambassador not once but three times, even inviting him for a banquet. Pacheco de Sampaio even had to postpone his departure because Qianlong wanted to have his portrait painted three times – one for the palace, another for the Jesuit mission, and a third as a gift for the ambassador.

This is not to say that the mission was without difficulties. Perhaps the biggest, Santos Alves noted, was actually making it happen, because of differences about the status of the embassy. Even though China’s power had diminished somewhat by the 18th century, it still saw itself as the centre of the world, and “barbarians were always considered subjects.” For the Portuguese ambassador, the key concept was parity between states; Jesuit priests were essential in finding common ground.

The remarkable stranger

Another highlight of the exhibition is a reproduction of the rarely seen 1245 decree from Pope Innocent IV nominating Franciscan Friar Lourenço de Portugal as Ambassador to the Mongol Empire; the original sits in the Vatican Secret Archives. Although little is known about Lourenço, there is no doubt that the Pope entrusted him with important missions, likely because of his legal expertise and diplomatic skills.

The mission to the Mongol Empire was a high-stakes one. At the time, the Mongol invasions had reached Vienna, deep in Central Europe, after a lightning-fast conquest of Eurasian territories. The Vatican, which had an overwhelming influence over European kingdoms, had been left guessing who the invaders were, neither Christian nor Muslim.

Amid “panic” in the Vatican, Lourenço was chosen to lead the embassy. While involved in the preparation and launch of the Pope’s initiative, for some unknown reason, the ambassador did not depart with the entourage. Another Italian diplomat ended up leading the mission, which succeeded in stopping the invasion. It is one of the many mysteries that surround this “remarkable stranger,” as Santos Alves calls him. A future research project is expected to shed light soon on Lourenço, and how he became one of the most influential members of Innocent IV’s court.

As in the other two sections of the exhibition, visitors explore the period through religious objects (European and Asian), luxury trade goods (porcelain, glass) and books (a 16th-century Portuguese edition of the Travels of Marco Polo) – “contemporary echoes,” as the curator calls them. Intense trade meant the same kind of luxury glass used for perfumes could be found in Portugal and in Indonesia during Lourenço’s time. “This was the 13th century, but everything worked: diplomacy, goods, people, perfumes, porcelains, Marco Polo…” Santos Alves said.

The idea of a “closed China” persists, but he noted, “today we know that cultural, commercial, and diplomatic contacts between the West and China in its various dynasties was more or less regular, though not constant.”

Other than showing the long duration of European-Chinese relations, the exhibition aims to bring to light the “learning process” in this relationship, the “fine tuning” of the approach, made of steps forwards and backwards over many centuries.

While tension – even outright war – existed between China and European powers at end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, relations with Portugal remained largely peaceful and positive.

Opened a few months after the visit to Lisbon by Chinese President Xi Jinping, and at a time described by both governments as the best ever in historical and economic relations, the exhibition also spotlights the importance of the bilateral “learning process.” A process that has borne fruit, according to Santos Alves, in the centuries of Portuguese presence in Macao and the city’s peaceful handover to China, 20 years ago – and sets the stage for a new beginning.

Three European Embassies to China is on display at Lisbon’s Museu do Oriente until 21 April. For more details, visit museudooriente.pt.