The Currency Museum at the University of Macau showcases currencies of all eras.

When visitors arrive at the Currency Museum at the University of Macau, they see a cowry shell, the oldest form of money that was used in China many millennia ago. Through the various collections, visitors explore the evolution of currency in China, and the world more broadly, moving from that distant past through to the present day.

The museum opened in April 2017, created by the university’s Faculty of Business Administration (FBA) and is housed in its main building. It showcases various forms of Chinese currencies – shell, metal, and paper – developed throughout its history, as well as those of Macao and Hong Kong, alongside Western currencies. Additionally, there are collections focused on local entities and traditions closely associated with currency.

Professor Jacky Yuk‑Chow So, dean of the FBA, said that they had three main objectives in setting up the museum: enhancing information retention, understanding currency history, and evaluating possible future currency. “In traditional education, students listen to teachers and retain 30 per cent of what they hear and forget the rest. But, if they do things themselves, they retain 70 per cent. If they can feel, touch and experience something, they have a stronger memory.

“We want to provide a platform for active learning for our students. Many business courses nowadays require ‘hands‑on’ experience after the lectures from the instructors,” So explained. “We hope that by reviewing the collections in the museum, the students can relate to what they learned in the classroom, especially for classes such as money and banking.”

Another objective is to allow students and the public in Macao to learn more about the history of money in China and in Europe. “Comparing the East and the West, students should be proud of the economic performance of ancient China and therefore motivate them to ‘Love China, Love Macao’,” So said. “In the Song dynasty [960–1279AD], China accounted for 40 per cent of the gross world product. Its currencies were very popular and welcome by many countries in Europe and Asia, including Japan.”

A solid grounding in the history may provide insight on the new digital currencies, allowing students to “assess if cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Litecoin can really become money, or are just commodities.” Whatever their conclusion, So stressed that “the technology behind Bitcoin and Blockchain cannot be overlooked” as it “will drive financial technology and the financial services industry.”

The dean said that he was satisfied with the results of the museum so far. “We have had many visitors from Macao and outside, including students, teachers, museum people, and the general public. Many have come from local secondary schools, as well as individual visitors from the mainland. All have been able to gain a greater understanding of currencies.”The museum is open between 10:00 am and 5:00 pm, Monday– Friday. While it is meant to “enhance teaching and learning for students at our university,” So again noted that the public is welcome to visit.

Building from scratch

The FBA decided to set up the museum, but with no budget to buy exhibits or even furniture, they turned to the community for help. They asked banks and companies for donations to purchase furniture, and approached the Macau Numismatic Society about members possibly lending or donating their collections.

The response was overwhelmingly positive. David Chio, president of the Macau Numismatic Society, saw the museum as an opportunity to promote their collections. With his support, members of the society gave and lent a variety of pieces for display. For their part, the banks donated antique furniture that is both attractive and precious.

In total, the faculty spent only MOP 200,000 (US$24,900), for the interior decoration and layout of the room that houses the museum. They also received support and contributions from government agencies, companies, local secondary schools, associations, and individuals

Historical currency

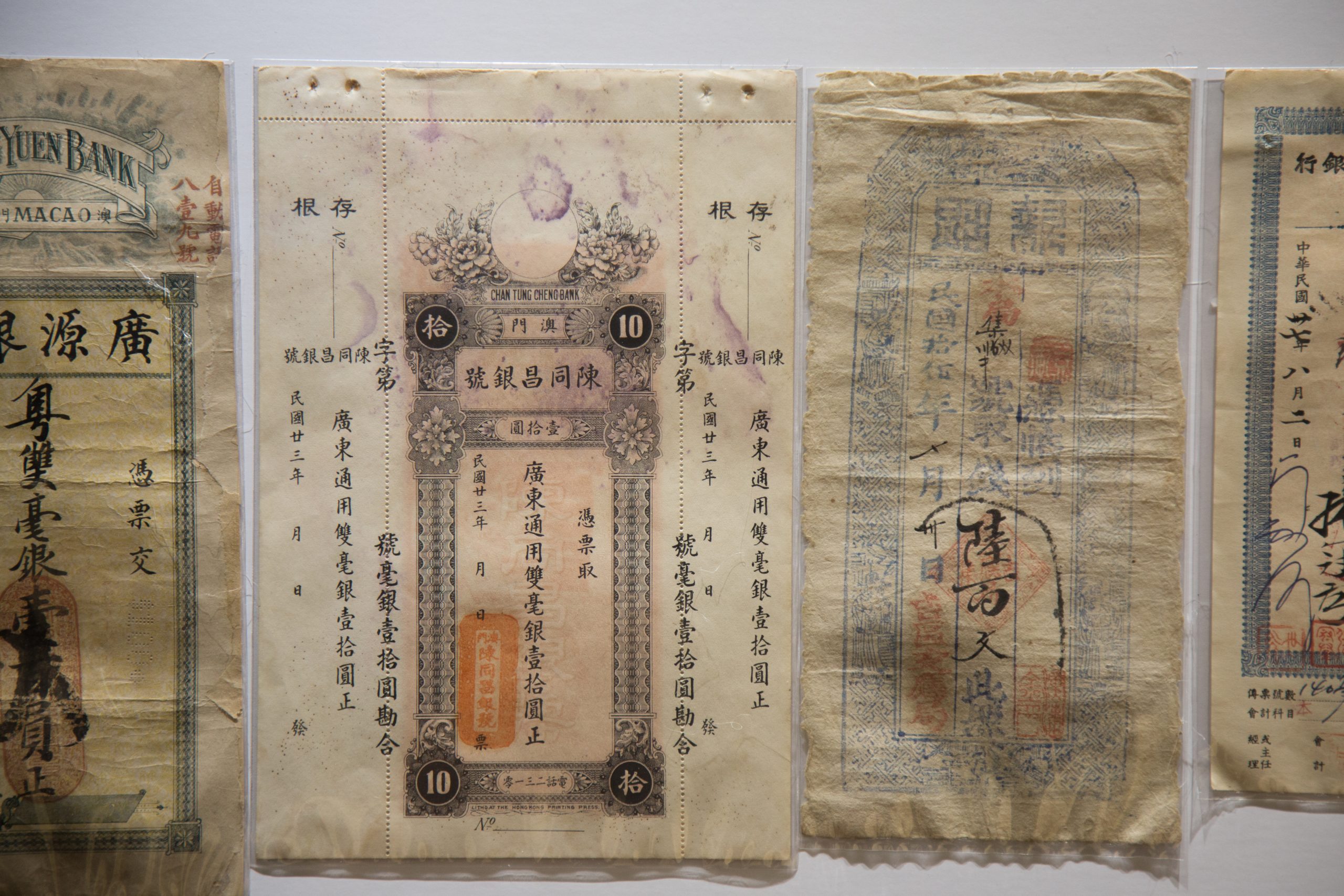

There are eight collections in total – including ancient Chinese coins, money from the Republic of China, and banknotes issued by banks in the People’s Republic of China and Macao. Coins and notes aren’t the only things on display. Photographs related to Macao’s Macao bandar’s notes from 1910s to 1940s banking industry comprise one collection while another includes a copy of an imperial edict issued by Emperor Qianlong (1735–96) authorising the establishment of a mint. Even red packets get their own collection, a reflection of their prominence in Chinese culture and close ties to currency.

The most valuable items are historical coins, which are kept in locked cabinets for security reasons. They date from several different dynasties – the Qin, the Song, the Ming, and the Qing – accounting for nearly 2,000 years of Chinese history. Those minted during the prosperous Song dynasty include coins from both the Northern Song (960–1127AD) and the Southern Song (1127–1279AD) periods. Some of these are extremely valuable and would sell for thousands of US dollars at international auctions.

Picking up where the imperial coins left off is a cabinet containing coins and paper money issued during the Republican period. These include banknotes issued during its early years, which are as large as a third of a sheet of A4 paper – far too big to fit into the wallets of today. There are also banknotes bearing the face of Dr Sun Yat‑Sen, father of modern China.

Money in Macao

The Macao collections include historical photographs as well as legal tender issued in Macao, including a five‑pataca banknote of Banco Nacional Ultramarino (BNU) in the 1980s. This may invoke a sense of nostalgia among those who remember that, at one time, Macao had a five‑pataca note instead of the five ‑pataca coins in circulation today. The collection includes a complete set of coins that have circulated in Macao, beginning with the first coins issued in 1952.

Two photos of the main BNU building, now on Av. Almeida Ribeiro, capture the history and change in Macao over the last century. Taken in 1907 and 1991, the two images show a building little changed in more than 80 years. The almost rural setting of the earlier photograph, however, has disappeared. Today, that quaint backdrop has been replaced by the towering skyscrapers of a thriving modern city.In 2012, the Bank of China issued 100‑pataca notes to mark its 100th anniversary.

The elegant design, which features an ink wash painting of a lotus with a vertical rather than a horizontal orientation, won awards. The bank donated a set of these notes to the museum collection.

Macao’s history with establishing its own banks began in 1902 with the first Macao branch of BNU. Then came the Hang Seng Bank, founded in 1935, and the Tai Fung Bank, founded by Ho Yin in 1942. During World War II, the Hang Seng Bank of Hong Kong moved to Macao to escape the Japanese occupation. Here it became the Rong Hua Bank, a name it retained for three years and eight months. The bank reverted back to its original name when it returned to Hong Kong after the Japanese surrender.

The Hang Seng Bank of Hong Kong has since been acquired by HSBC, and the Hang Seng Bank of Macao became Delta Asia Financial Group in 1993.

The Wing Hang Bank Ltd was set up in Macao in 1967, but was later bought by the Overseas‑‑Chinese Banking Corporation. In 1972, gambling tycoon Stanley Ho set up Seng Heng Bank, which was acquired by Industrial and Commercial Bank of China in 2009, becoming ICBC Macau.

Red packets

One of the museum’s most unique collections focuses on red packets, which Chinese use to gift money during Chinese New Year and other auspicious occasions. It includes a variety of designs and styles that illustrate the ubiquity of these colourful envelopes.

There are old style and rare red packet collections issued by Tai Fung Bank and HSBC made of golden paper and decorated with symbols of long life. Others feature the lotus, the symbol of Macao, while one given out by Christian churches is decorated with verses from the Bible and images of the Holy Family. From Macao’s luxury hotels, we see red packets crafted from silk and leather. Even international fast-food giant McDonalds embraced the tradition, issuing them to mark its 25th anniversary in the city.

Changing face of money

On one wall is a history of coins and money, in China and the West, starting from the cowry shells of the Neolithic period. Centuries later, this type of commodity currency gave way to proto‑money, as ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia began using units of weight – measured against gold and silver bars respectively – to facilitate trade.

Metal coins first appeared in China near the end of the Shang dynasty. As ancient China experimented with different shapes – shell, spade, knife – the West continued to rely on other systems. The first minted coins in the West would not appear until the reign of Alyattes (610–560BC) in Lydia, an area which is now Turkey.

The rest of the ancient world soon followed, developing their own metal coins and pioneering new elements in the materials and design of coins. Alexander the Great (336–323AD) became the first king to put his own portrait on a coin; earlier Greek drachma favoured images of gods and animals. Emperor Qin Shi Huang (221–210BC) introduced a single, uniform currency for the new Chinese empire comprised of gold and copper coins. The design – round coins with a square hole in the centre – remained common in China until the 20th century.

The future of currency may abandon physical materials altogether, though, moving beyond coins and banknotes to purely digital cryptocurrencies. Despite the rising trend in cryptocurrencies, new forms emerge almost daily. Professor So remains sceptical, arguing that “e‑money will not replace currency. The risks are too high and they are too erratic.”

He’s not wrong. Most cryptocurrencies don’t survive past the first few months, leaving investors with so‑called ‘zombie coins’ that retain none of their original value. For So, they are “a commodity which you can invest in, but not a currency.” Yet as the museum demonstrates, currency changes over time, taking on new forms and issuing from new sources. Understanding this long history will give students the grounding they need to evaluate new innovations – including cryptocurrencies – as the evolution of currency continues into the future. Different forms of currency