Archives of Macao achieve global recognition

Lau Fong, Director of the Archives of Macao, has devoted several years of her life to a unique set of documents that form an important part of the city’s history. Now her efforts have been recognised by the United Nations.

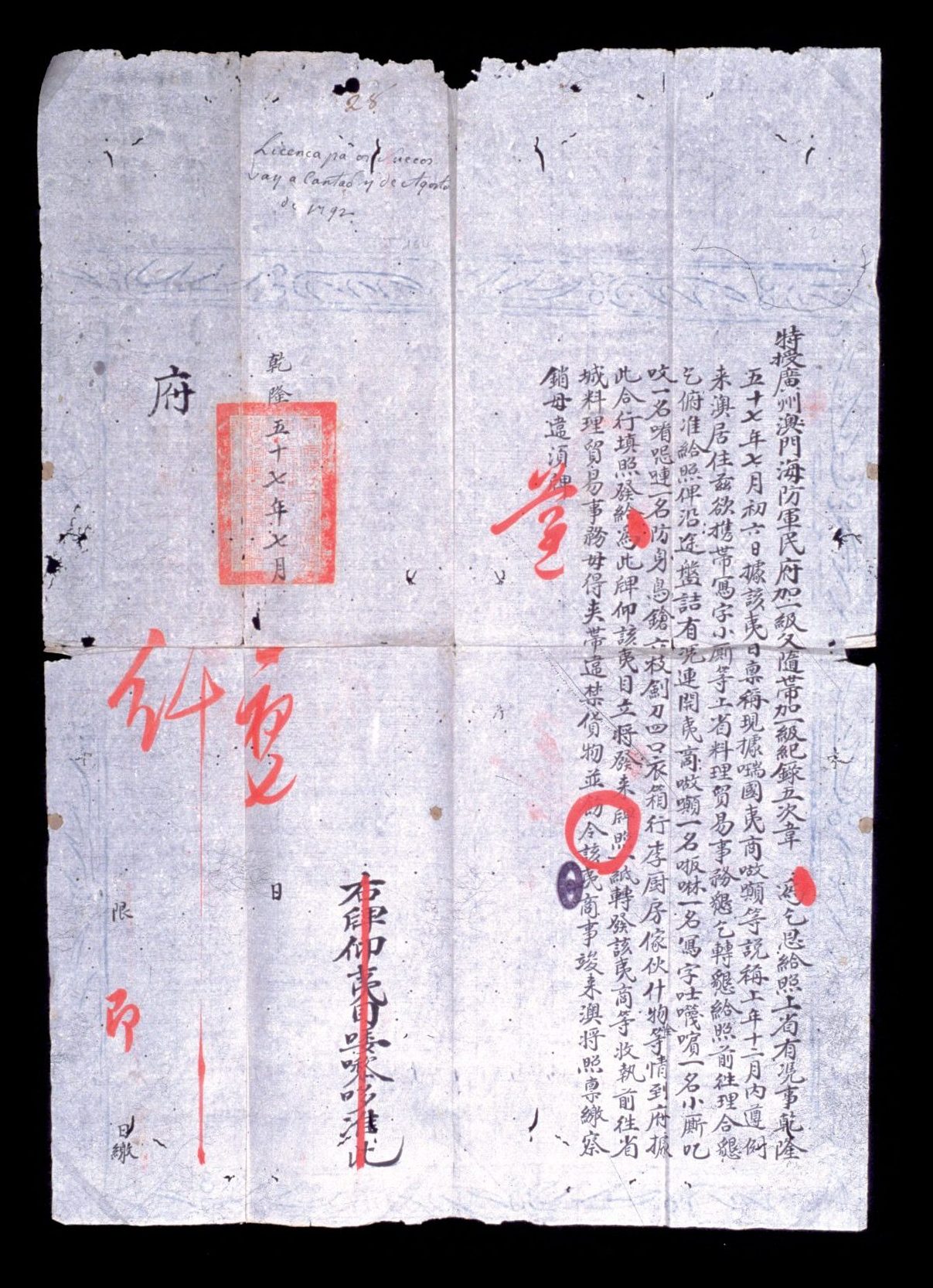

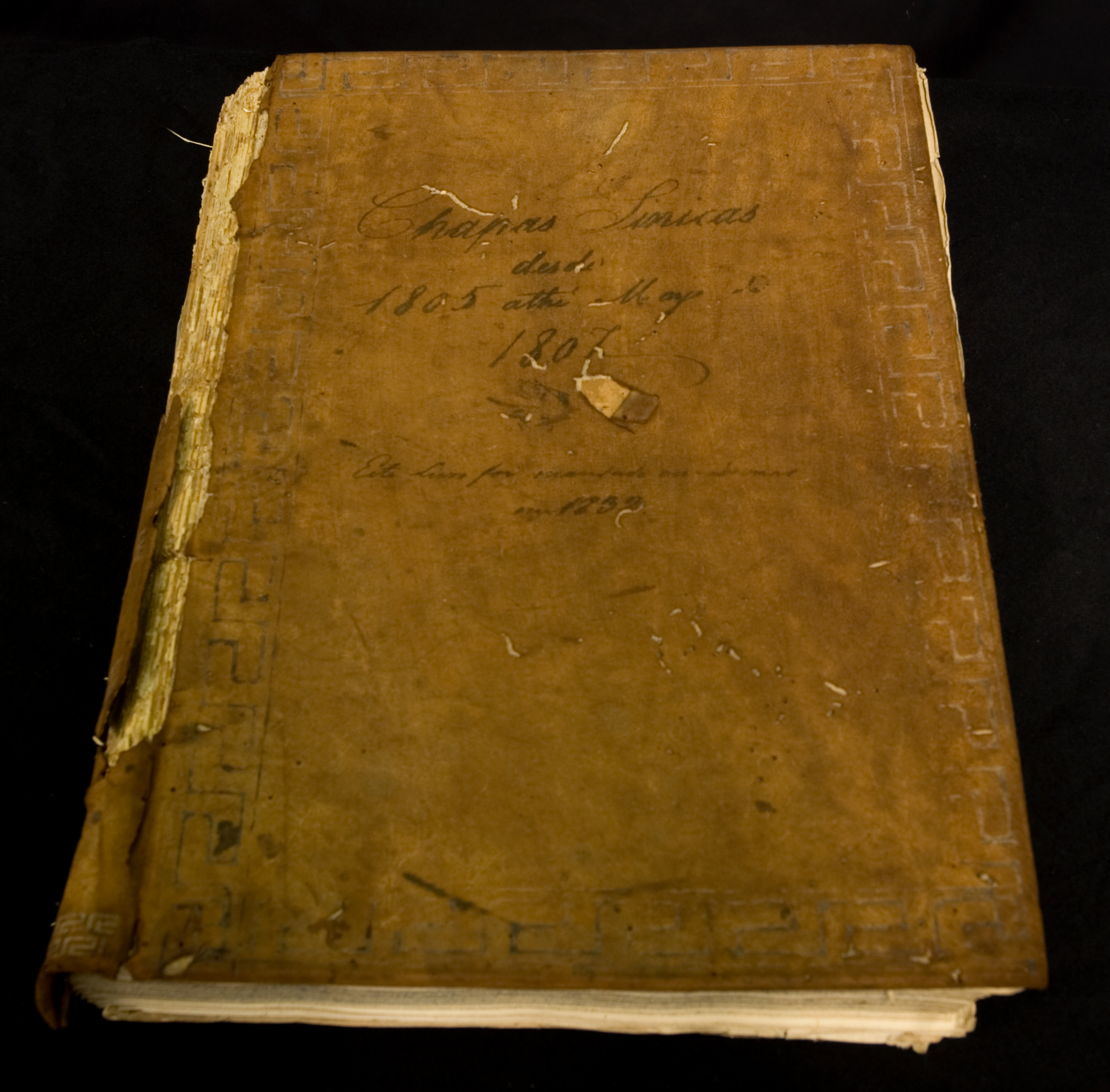

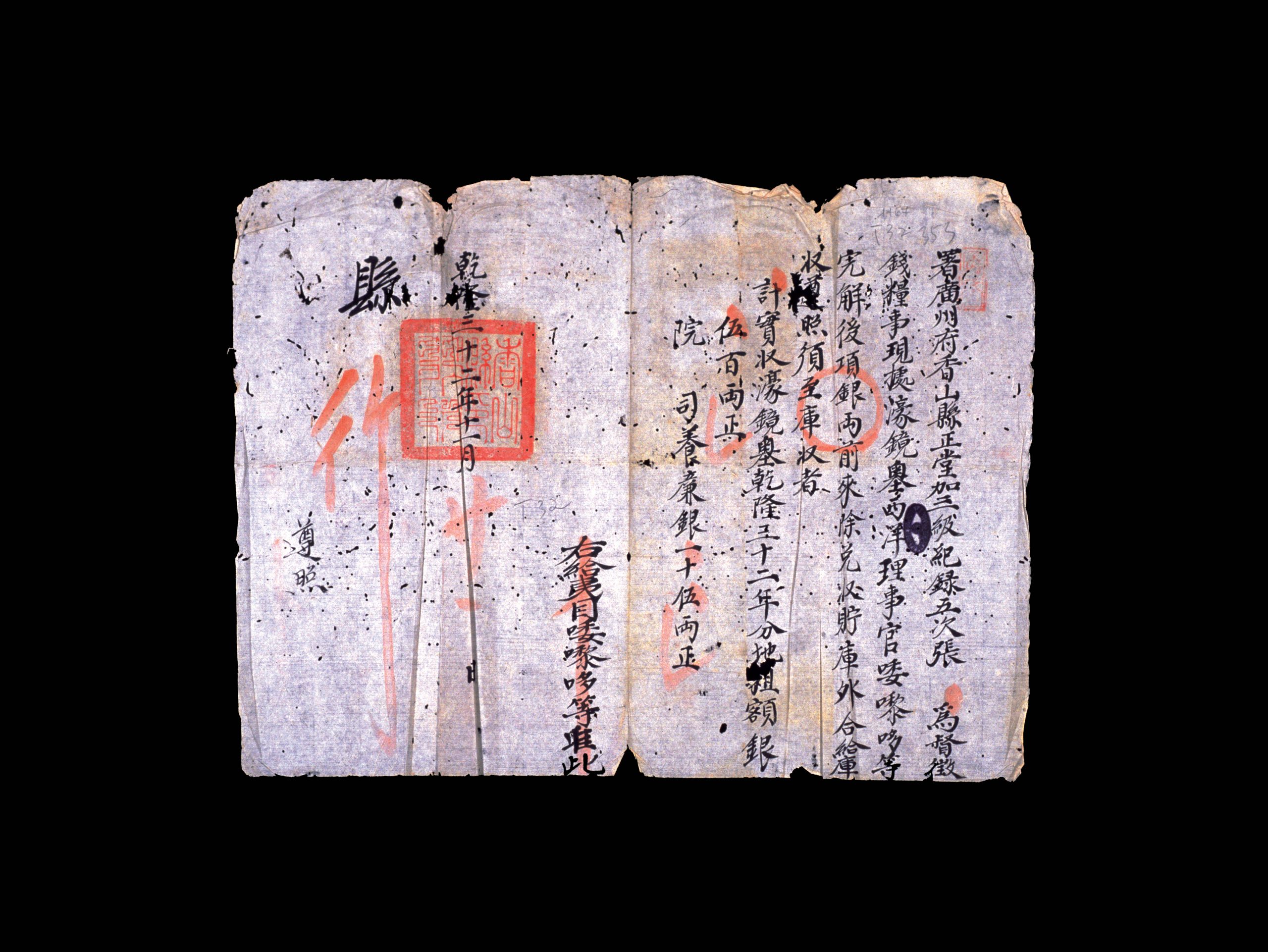

This May, the UNESCO Memory of the World Committee for Asia and the Pacific (MOWCAP) voted on whether to register the collection Official Records of Macao during the Qing Dynasty (1693–1886), originally entitled Chapas Sinicas meaning “Chinese documents.”

The collection was jointly nominated by the Archives of Macao and Portugal’s National Archive of Torre do Tombo where the original documents are stored. Under the recommendation of the MOWCAP Register Subcommittee, the inscription was unanimously approved by participating member states. This meeting, which was held in Hue, Vietnam, inscribed 14 documentary heritage items from 10 countries on the Asia‑Pacific Register of the Memory of the World.

“We have applied for the collection to be included in the Memory of the World Register,” says Director Lau, “[and] will learn of the decision next year from the Paris headquarters. [The records] are the history of Macao.”

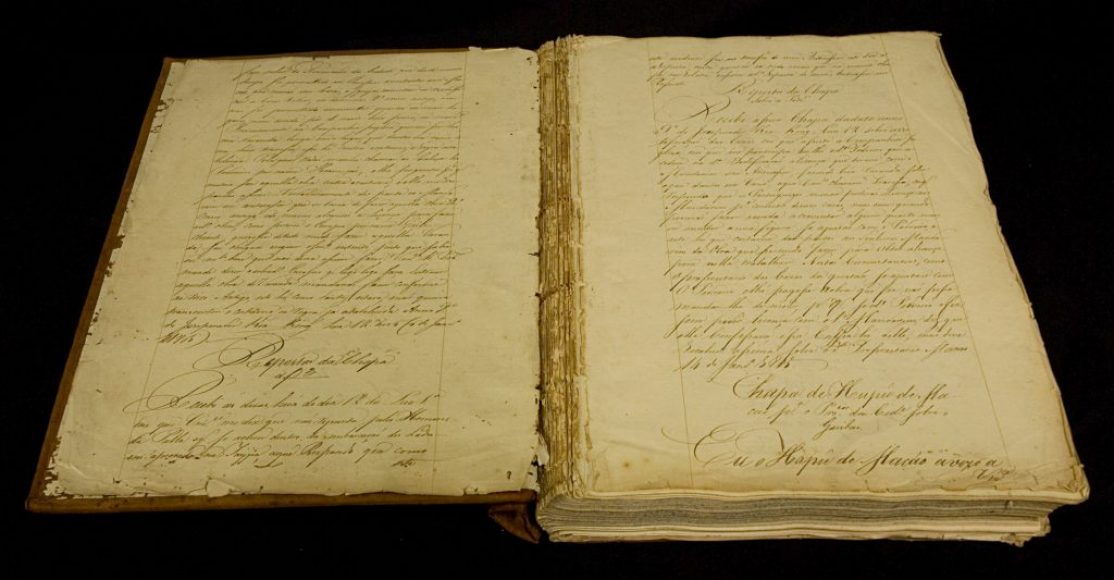

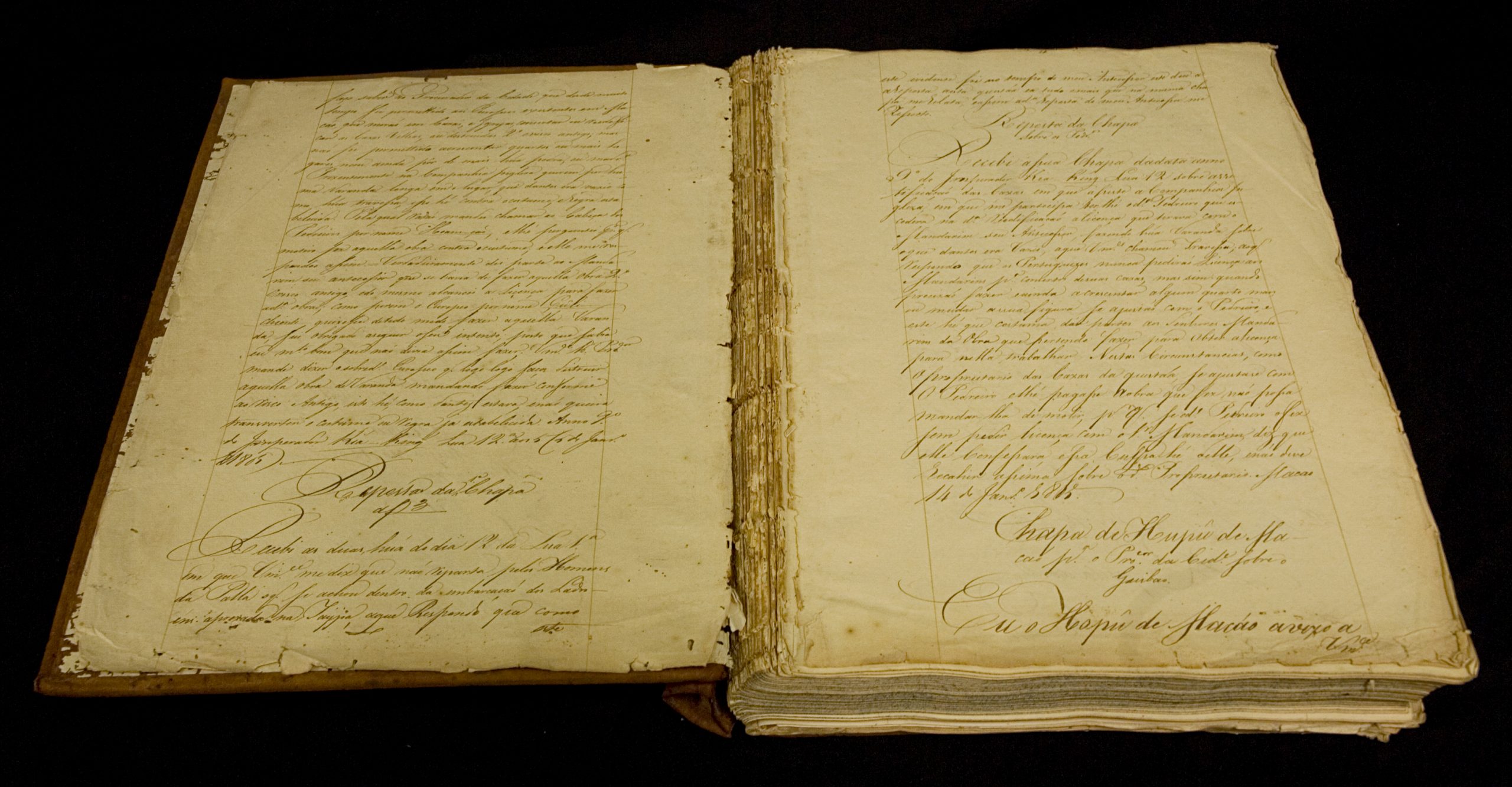

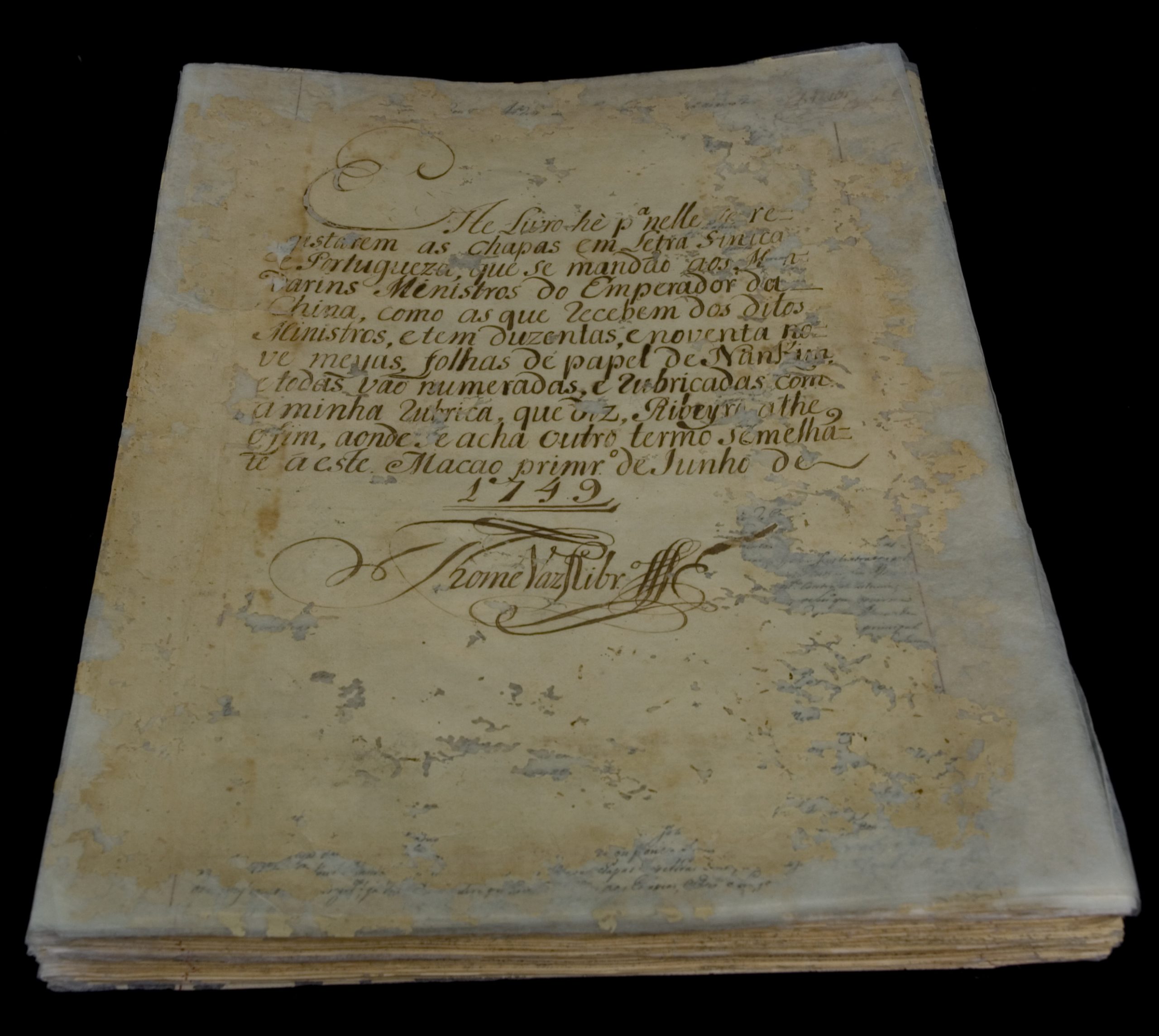

Chapas Sinicas comprises a total of 3,600 documents, including over 1,500 official letters written in Chinese, five volumes of letters translated into Portuguese and copied and maintained by the Loyal Senate (Leal Senado) of Macao and four packets of miscellaneous documents. The bulk of the collection consists of official correspondence between sub‑prefects of Macao, magistrates of Xiangshan and other Chinese officials and the procurators of the Loyal Senate.

Lau points out its significance for not only the history of Macao but the whole world. “They show the port of Macao as a centre for exchange between East and West and its important role in promoting international cultural exchanges. They also show the process of colonial expansion of Western powers and the rapid changes in Asia, especially in China. They help us understand the unique foreign policy of the Qing government toward the aggression of Western powers from its peak to its decline at the end of the 19th century and the unique role played by Macao in this historical transition.”

Until the First Opium War and the establishment of Hong Kong as a British colony in 1842, Macao was the sole port in China open to foreign ships and the only place in the country with a resident foreign population including families, Christian schools, seminaries and missionaries. The documents present a rare and vivid picture of two centuries of life in Macao and are one of its historical treasures.

Its value is attested by the number of scholars who have come to read through the collection and consult with archival experts, as well as its publication by the Macao Foundation. “Many researchers come to Macao, from mainland China, the United States, France, Japan, Britain and other countries to consult the copies of documents we have here,” Lau confirms.

Chapas Sinicas resiliently survive a long journey

At the end of the 19th century, the documents were taken to Portugal and stored in the National Archive of Torre do Tombo in Lisbon. Few people at the time realised their importance. No one possessed the linguistic or scholarly competence to read or evaluate them, so they slept peacefully in their boxes.

During the first half of the 20th century, Portugal was fortunate to avoid the fate of many countries in Europe that were occupied, bombed and damaged by two World Wars. The boxes were not disturbed; the documents remained untouched and preserved in good condition.

In the early 1950s, Fang Hao, a Jesuit priest and professor of history at National Taiwan University, visited the National Archive of Torre de Tombo. He consulted Chapas Sinicas and recognised the importance o f the collection despite its lack of organisation or classification.

The documents help us understand the unique foreign policy of the Qing government toward the aggression of Western powers from its peak to its decline at the end of the 19th century and the unique role played by Macao in this historical transition

Numerous scholars followed Fang to conduct preliminary research on the collection, including Pu Hsin‑Hsien, a professor from the University of Madrid. Their initial findings attracted the interest of Chinese history scholars around the world.

A full survey of the documents was not conducted until the late 1980s when former Director of the Archives of Macao Isau Santos went to Lisbon. He took microfilms of the documents, catalogued them and began the long and difficult task of preparing them for publication.

Current Director Lau has also devoted a number of years to studying the collection. A graduate of history, she possesses a competent understanding of the classical language used in the documents which is substantially different from modern Chinese (introduced and put into common use in the mid‑1910s). During the imperial period, civil servants used classical language for official documents which was not readily accessible by ordinary civilians. “I could understand most of the documents,” says Lau who still needed to consult dictionaries and historical references in order to fully comprehend every detail. “Others would consider this task tedious, but I enjoyed it. It brought me into history. The documents give insight into people’s daily lives. It was like reading a novel.”

In 1995, using a version on microfilm, the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macao published the catalogue of Chapas Sinicas in Chinese and Portuguese. The Macao Foundation published the Chinese and Portuguese records, respectively, in 1999 and 2000.

In 2015, the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macao and the General Directorate for Book, Archives and Libraries of the Government of Portugal signed a memorandum of understanding for co‑operation in archival domains. This facilitated co‑operation between the Archives of Macao and the National Archive of Torre do Tombo in bilateral collaboration for the conservation and digitisation of the collection as well as jointly nominating Chapas Sinicas to be listed on the MOWCAP register. Thanks to their efforts, online access to the collection has enabled scholars and interested readers to consult the document at any time from anywhere.

Regarding the issue of ownership, Lau admits that she has not given much thought to whether the documents should be returned to Macao. “It is a complicated issue with political and diplomatic implications. The physical location of the records is not so important. Chapas Sinicas belongs to the world. We (the two archives) work together, just as we did for the application to MOWCAP.”

A wealth of content

The records contain the terms and limitations established for the Portuguese administration in Macao, reports and petitions submitted by the Portuguese authorities based in Macao and replies received from the Chinese authorities in Guangdong. There is also official correspondence reflecting the unique relationship between Chinese and Portuguese authorities and Portugal’s special “leaseholder” status. Most importantly, the collection is a manifestation of the very good understanding, collaboration, peaceful coexistence and harmony between the Portuguese authorities of Macao and Chinese authorities of Guangdong spanning more than 200 years.

The documents also include accounts, letters, deeds, contracts and other documents that reflect urban development, industrial and agricultural production, trade and commerce, society and conditions of everyday life.

“The documents deal with many aspects of relations between Chinese and Portuguese institutions,” states Lau. “These include issues of law and sovereignty, such as the application of Chinese law in Macao, the status of foreigners in Macao, legal cases and public order… In addition, some documents relate to economic and trade matters, such as taxes and donations, rents, smuggling and prohibition of opium. Some are about religious issues, such as unlawful preaching in China, oppression of Catholics in China and selection of missionaries.”

Diplomatic matters are also documented, such as the presence of British individuals and organisations in Macao, relations between Macao and other European and Asian countries, the movement of foreigners and the establishment of embassies, anti‑smuggling efforts, shipping‑related taxation and movement and inventory of ships and port traffic. Construction of civil and military buildings and illegal structures are also addressed.

According to Lau, “In modern colonial history, the most important and influential players were traders, missionaries, middlemen in trade and important officials. The collection, taken together, is the story of these characters.”

Documenting a melting pot of culture and people

The collection reflects Macao’s unique global status and role at the time. As it was the only legal port of entry into China, ships from all over the world came through, including Sweden, Russia, Holland, Denmark, Korea, Vietnam, Brunei, the Philippines, Britain, France and the United States.

Foreign ships that wished to proceed to Guangdong needed to obtain an entry permit in Macao, have their cargoes examined and approved and employ an interpreter, a middleman and pilot before they could make the journey up the Pearl River. Additionally, the Guangdong government imposed a limit on the number of foreign vessels that could enter Macao. Major import/export commodities mentioned in the documents include salt, sugar, cotton, rice, tea, saltpeter, opium and tobacco. The export of Chinese labourers is also mentioned in some of the records.

The collection is a manifestation of the very good understanding, collaboration, peaceful coexistence and harmony between the Portuguese authorities of Macao and Chinese authorities of Guangdong spanning more than 200 years

Macao, 1767 | Photo by Eric Tam

“The records also reflect Macao society at that time,” says Lau. “They touch upon the lives of ordinary people, urban construction, industrial and farm production and exchanges between China’s provinces and western countries. They show the development of multi‑culturalism in Macao over the centuries. For example, interracial romance and marriage between the Portuguese in Macao and foreigners, mainly those from around the South China Sea and further into China, gave rise to an ethnic group called the Macanese who later played an important role in bridging the gap between the East and the West.”

“Through these [multi‑cultural] exchanges, Western ideas of science and democracy as well as the Christian ideal of equality were introduced into China. They resulted in changes in Chinese society and later led to civic demand for social and political reform,” which exchanges went both ways. European life was seasoned with a touch of oriental flavour, and Chinese tea cultivation made its way to some territories of Portugal and later to Brazil. Confucianism, with its principles of altruism, social justice and governance with virtue, was brought to Europe and influenced philosophers during the Age of Enlightenment.