A lot has changed in Macao in the past 200 years, not least the physical size of the territory. In the 1820s, as a trade post for the Portuguese in China, Macao’s landmass was less than a third of its current area. Places that exist today thanks to land reclamation projects were shorelines and sea when the English artist George Chinnery made his highly evocative sketches. What’s remarkable, however, is just how much of Chinnery’s version of the city remains the same.

Chinnery was born in 1774, in London, though he spent most of his adult life in Asia. He sailed for India at the turn of the century, where he established himself as a leading artist in the British community. In 1825, Chinnery relocated to Macao and lived here until his death in 1852. His remains lie in the city’s Old Protestant Cemetery.

Drawings, oil paintings and watercolours made by Chinnery during this period depict Macao as an enchanting city of Portuguese architecture, cobbled streets and Chinese temples. He captured bustling hawker markets and wealthy European families, as well as poignant landscapes.

Chinnery has gone down in history as a rambunctious character. He was immortalised as Aristotle Quance in James Clavell’s novel Tai-Pan, and again in Timothy Mo’s celebrated novel An Insular Possession, appearing as the corpulent painter Augustine O’Rourke. While literature has portrayed Chinnery a debt-laden hedonist, he was also a genuine talent. Patrick Conner, who wrote the first in-depth study of Chinnery’s life and work, called him “an international star, a really extraordinary artist” and praised his “incredibly fluent drawings of the China coast.”

Here, Macao magazine offers a taste of Chinnery’s legacy. Familiar scenes and structures reveal just how much of the city appears, architecturally at least, untouched by the passage of time. Ultimately, this is testament to Chinnery’s artistic knack – but also Macao’s commitment to balancing the demands of development with cultural conservation.

Ruins of St Paul’s

The Ruins of St Paul’s – named for the college that once stood on this site – is Macao’s most iconic landmark. The distinctive edifice that survives today was part of the Church of Mater Dei, built by the Jesuit order in the early 17th century. It was one of the largest Catholic churches in Asia until a devastating fire burned all but the façade to the ground. The blaze took place during a typhoon in January 1835; Chinnery made his sketch a mere three months earlier.

The craftsmen who worked on the Church of Mater Dei (meaning ‘mother of God’) were Japanese Christians banished from Japan in the 1580s. Their carvings in the church’s façade are rather unorthodox. They incorporate the likes of dragons and Chinese-style guardian lions, as well as nautical motifs including a Portuguese ship.

While Chinnery’s pen and ink drawing, The Church and Steps of St. Paul, does not reveal these details, what he did capture is essentially what modern-day visitors get to see. There is little to suggest a roof and four walls stand behind the façade, or that Chinnery’s experience of the building would have been of a fully functional religious complex instead of the ruins found there today.

Archaeological remains of St Paul’s College can also be seen at the present-day site, hinting at the opulence of what was once the first Western-style university in East Asia.

Holy House of Mercy

The Santa Casa da Misericórdia (‘Holy House of Mercy’ in English) sits just south of the Ruins of St Paul’s. This famous Portuguese charity was established in 1498 to protect vulnerable members of society, such as the sick, disabled and very young.

The Macao branch was set up in 1569, by order of the then-bishop of Macau, Belchior Carneiro Leitão, in a purpose-built neoclassical building on Senado Square. One of its primary roles was to support the widows and orphans of sailors lost at sea, and it also housed the city’s first Western medicine clinic.

In Chinnery’s sketch, you can spy the Holy House of Mercy’s triangular cornice poking out from around a larger building in the foreground (it is the stark white structure in the photograph). When he drew his Crowd outside the Casa da Misericordia and Leal Senado in 1840, the institution had been offering social welfare services to the city for 271 years. Little has changed, in that regard, though the Holy House of Mercy now houses a valuable collection of Catholic relics, too. These bear testimony to the history of Western culture introduced to China through Macao. Relics include the skull of the Bishop Belchior Carneiro Leitão along with the cross he was buried with. Macao’s Holy House of Mercy Museum also displays the institution’s original, handwritten commitment, dated 1662.

St Dominic’s Church

A three minute walk across Senado Square takes you to the baroque, lemon yellow St Dominic’s Church. Chinnery made several drawings of charming St Dominic’s around 1825; by then it had already served as a place of worship for almost 240 years. Most sketches featured hawkers and market stalls out in front, suggesting the square was a popular place of trade at the time.

St Dominic’s was built not by the Portuguese, but by Spanish Dominican priests who came to Macao from Mexico. The building has had several functions since then, and was even the home of the first Portuguese-language newspaper in Macao – A Abelha da China (the ‘China Bee’). A Abelha da China was a short-lived endeavour, launching in 1822 and winding up less than two years later.

In 1834, less than a decade after Chinnery helped immortalise the church, Portugal’s then-prime minister, Joaquim António de Aguiar, decreed that all religious institutions within the Portuguese empire be dissolved and their assets seized by the state. During this period of secularisation, St Dominic’s building was a barracks, a stable, and an office – before returning to its original religious purpose in the later 19th century.

St Francisco Barracks

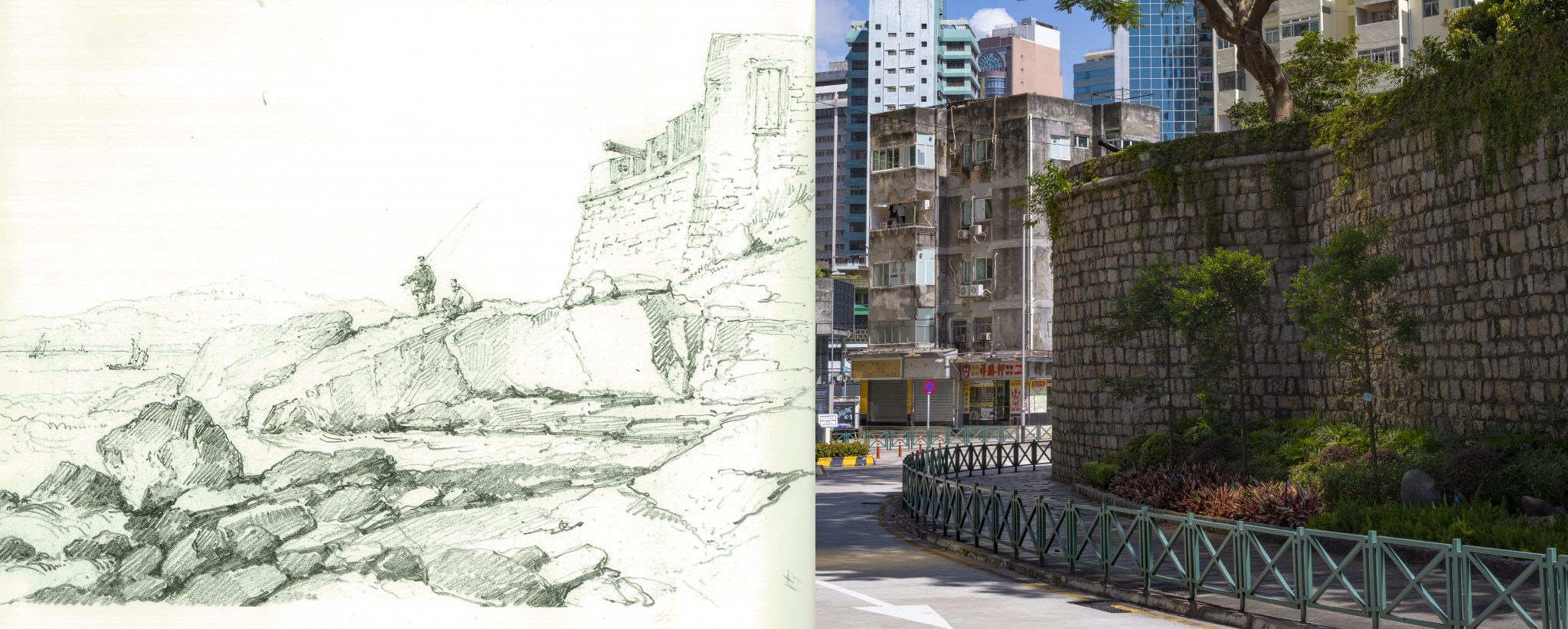

One of the most striking changes Macao has undergone since Chinnery’s day has been the extensive reclamation of land from the sea. This is evident when comparing the artist’s sketch of the St Francisco Barracks with a recent photograph.

The former attests to the fact that the site’s sturdy brick wall was once the waterfront; Chinnery depicts a figure fishing off now-vanished rocks at its base, and junks sailing by. But today, as the photograph shows, the curved wall is ringed by the busy Avenida da Praia Grande – not Praia Grande Bay.

The barracks began life in the early 17th century as an artillery battery, with a long-barreled cannon that could fire a 16 kilogram ball a distance of almost 2.5 kilometres, and a convent. The convent was demolished in 1864, to make way for barracks for soldiers. The barracks currently serve as headquarters to Macao’s security forces and police.

A-Ma Temple

Built in 1488, on the peninsula’s southwestern shore, the A-Ma Temple predates the Portuguese administration of Macao. It was already of great antiquity when Chinnery sketched its distinctive gate pavilion and guardian lions in 1833.

The temple is dedicated to the Chinese sea goddess Mazu (also known as Tin Hau or simply A-Ma, meaning ‘mother’). Some believe it is the source of the territory’s name; that ‘Macao’ is a Portuguese rendering of the Cantonese A-Ma-Gau, or ‘mother’s bay’.

Chinnery’s drawing, The A-Ma Temple with two sketches of a boatman at his oar, appropriately links the sacred structure to seafarers – Mazu’s principal devotees. The temple merges Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism and Chinese folk beliefs within its six-building complex.

Chinnery’s artwork reminds viewers that Macao is a city where history gracefully entwines with the present. His drawings serve as a portal to the past, and offer evidence of the history’s ongoing role in the culturally rich life of Macao.