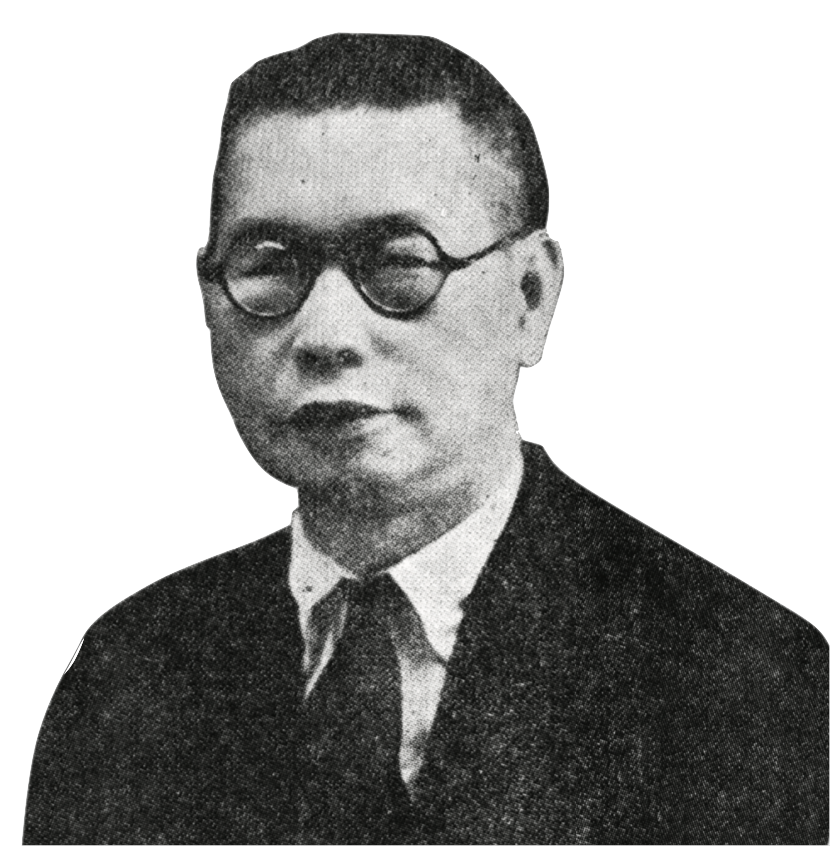

Leung Yan-ming – a hero of the anti-Japanese movement who dedicated 33 years of his life to local education

Leung Yan-ming was a pioneer of modern education in Macao, a political activist, and leader of the anti-Japanese movement during World War II. His years-long commitment to opposing Japanese aggression likely cost him his life, gunned down 24 December 1942 by an unknown assailant.

An accomplished calligrapher and poet, Leung also served in prominent roles in civic and government organisations in addition to his roles as educator and activist. He accomplished much in a life tragically cut short. Today, Leung is remembered as a hero of the anti-Japanese movement and a champion of education in Macao, dedicating 33 years of his life to serving primary and secondary students, as well as the ordinary public.

Dawn of a new era

Born in 1885 in Xinhui, Guangdong province, Leung studied at the Nanhai Model School and Guangdong Normal College, two of the leading educational institutions in Guangzhou at the time.

He came of age in a period of revolutionary ferment, in which the Cantonese played a leading role. One of the areas of greatest change was education. Reformers wanted to introduce the teaching of maths, science, geography, and other modern subjects to replace the study of Chinese classics that had been the basis of education in China for centuries.

In 1905, the Qing dynasty abolished the imperial examination system that relied on knowledge of Chinese classics and literary style. The abolition led to a search for a new form of education to equip young people for the modern world. Swept up in the movement, a young Leung endeavoured to make his own contribution to improving the schooling of China’s children. His work began in 1909 when his father, Leung Tai-cho, decided to move the family from Guangzhou to Macao.

Leung set up a new school in Macao the same year, in a former bookstore on the second floor of a downtown building; he called it Sun Sat Middle School (崇實學校), meaning a school that promoted honesty. In 1910, through the introduction of two members, he joined the Tongmenghui, a revolutionary party led by Dr Sun Yat-sen that was the forerunner of the Kuomintang (KMT), or Nationalist Party. Founded in August 1905 in Tokyo by Sun and his associates, Tongmenghui existed as a secret society and underground resistance movement aimed at overthrowing the Qing dynasty.

In April 1911, Leung and other members of the Tongmenghui embraced a symbolic act of disloyalty to the Qing empire popular among revolutionaries: the cutting of pigtails. They organised the demonstration in the school, risking severe punishment by defying the government mandate that all men wear a pigtail.

Six months later, in October 1911, a military uprising in Wuchang, Hubei province, set off the Xinhai Revolution. Revolts and uprisings swept across the country, drawing in people from varied walks of life, including revolutionaries like Leung; the Qing dynasty fell within months, bringing an end to imperial rule.

Building the school

Under Leung ’s leadership, Sun Sat Middle School developed rapidly, becoming one of the best-known schools in the city. It expanded to offer classes from primary to early middle school, as well as housing for faculty and students in a three-storey apartment building in the Nan Wan area in Macao.

Instruction focused on preparing students for education in the mainland, arming them with the tools needed to keep pace with advancements. To this end, Leung set up a Boy Scouts troop and added military training in the middle school.

He ordered a batch of fake rifles from Guangzhou for training, but met with strong opposition from the Portuguese government, which did not allow military training outside its control. While Leung was forced to drop the planned training exercises, he retained more than 100 rifles, storing them on shelves lining both sides of the school’s main assembly hall.

In 1920, Leung helped found the Macao branch of the Chinese Education Association (CEA). The organisation sought to promote the unity and development of teaching in the city, emphasising the importance of cultivating Chinese language education, culture, and patriotism. They founded a free school the same year, aimed at providing education to ordinary people.

Most schools for Chinese living Macao were private, and while the organisations running them tried to keep tuition fees low, some children could not afford to attend. Others came to the city as teens or adults without an education. Free schools granted many ordinary Chinese a unique opportunity to receive education. In 1927, seven years after opening the free school with the CEA, Leung founded Kiang Wu Free School.

Leung dedicated more than 30 years of his life to developing and promoting education in the city. Many of the graduates of his school went on to play prominent roles in the life of Macao.

Fighting for a nation

For Leung, his teaching and political work were part of the same struggle: to strengthen and modernise China. Having succeeded in overthrowing the Qing dynasty, the three-year-old government of the Republic of China faced another imperial threat: Japan. In January 1915, Tokyo issued the Twenty-One Demands, a list of stipulations designed to dramatically expand Japanese control of Manchuria and China. The blatant attempt to transform the new republic into little more than a puppet state prompted sharp protests across China. Leung joined with others to organise an association to boycott Japanese goods and “save the nation.” They were not alone.

Japanese exports to China fell 40 per cent in the wake of the nationwide boycott. Pressure from Britain and the US forced Tokyo to drop the most aggressive set of demands which would have, among other things, given Japan control of China’s finance and police. The reduced Thirteen Demands remained a severe blow to Chinese sovereignty, solidifying the losses accrued in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95). The new government, in no position to reject it, reluctantly signed the treaty 25 May 1915.

In the years that followed, anti-Japanese sentiment remained high. On holidays, Leung organised students and faculty to take part in local activities to promote the boycott. When Japan received parts of Shandong province in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, a mass demonstration by over 3,000 Beijing students sparked a wave of protests across the nation. Dubbed the May Fourth Movement for the day of the first protest, it marked a sharp upsurge in Chinese nationalism, political mobilisation, and populism.

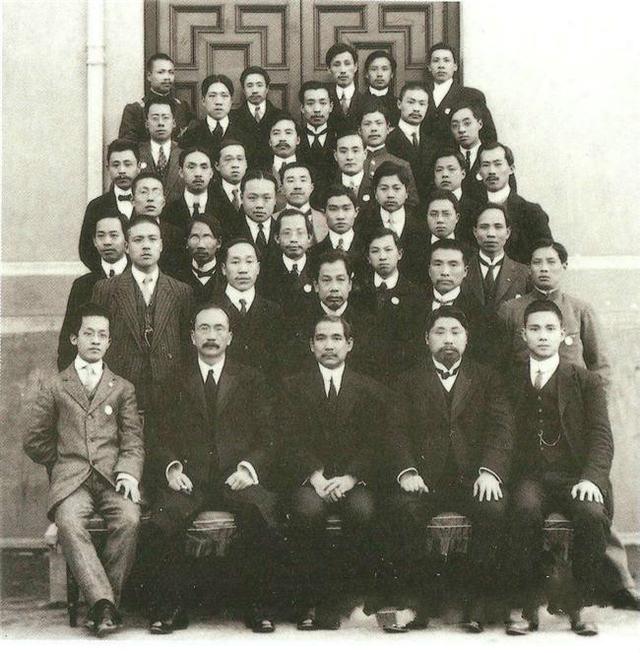

In 1921, Leung and other members of the CEA met with Dr Sun Yat-sen in Guangzhou. Dr Sun encouraged Leung to bring together all sectors of Macao society and promote patriotic businesses. The following year, Leung led a group of more than 3,000 teachers and students in a mass demonstration protesting the nation’s shame at the hands of Japan and other foreign powers, and calling for national revival.

When Dr Sun died in 1925, Leung chaired a meeting of 20,000 in a ceremony to mourn the death of a man now known as the “Father of the Nation.”

Leung remained committed to KMT even after its founder’s death, playing a prominent role in the work of the Macao branch, serving as a member of its standing committee, and attending meetings as a deputy of its Zhongshan and Guangdong branches. Leung also served as vice chairman of Kiang Wu Hospital, a senior official of the city charity Tong Sin Tong, and a committee member of the CEA.

A new war

After Japan launched its all-out war against China in July 1937, Leung threw himself in the struggle. He strongly promoted the boycott of Japanese goods, and encouraged his students to bring copper coins for the collection box passed in each class to raise money for the war effort. He raised funds to treat KMT soldiers injured in the war, particularly the devastating Battle of Songhu.

Fought in and around Shanghai between August and November 1937, it was one of the bloodiest battles of the Second Sino-Japanese War: 250,000 Chinese and 40,000 Japanese died during the four months of brutal urban warfare. Historians have called it “Stalingrad on the Yangtze,” a reference to the single deadliest battle of World War II.

Leung campaigned passionately to raise public awareness about the war. This prominence in the anti-Japanese movement brought him to the attention of its agents in Macao. Despite receiving death threats for it, he continued his work.

After the Japanese captured Hong Kong in December 1941, Leung ’s importance to the movement only increased. The government concentrated its overseas Chinese work in Macao, the only place in East Asia not under Japanese control. Leung secretly monitored the activities of Japan and its collaborators, reporting them to the government in Chongqing, where it had moved the capital after the fall of Nanjing in 1937.

Then the threats became reality: on Christmas Eve 1942, as he was walking back to his school in the evening, Leung was shot dead. He was 57. More than 1,000 people attended his funeral; when the procession passed the Japanese consulate, mourners expressed their anger and protest. Within a week, Lin Zhuofu, leader of the Hong Kong and Macao KMT and principal of Zhongshan Middle School, was also shot to death.

No arrests were made for either murder. It is widely believed that Japanese agents assassinated both men to halt their anti-Japanese activities. But the Portuguese government in Macao, concerned with maintaining its neutral status in the war, dared not conduct a vigorous investigation into the killings.

The central government in Chongqing lauded Leung in death with a telegram praising him as “First among Overseas Chinese to die for their country in Macao.” On 29 March 1943, it designated him as a martyr.

The poetry society Leung helped establish in 1927 published a collection of his poetry after the war ended in September 1945. Founded in 1920, his school operating under a new principal, continued to serve the city until 1961.

On 3 September 2014, nearly 70 years after Japan surrendered, officials of the Macao Education and Youth Affairs Bureau held a meeting with teachers and students to remember those in the city who had given their lives during the Second Sino-Japanese War, including Leung Yan-ming.

They recalled his prominent place in education as chairman of the Macao Chinese Education Association and principal of Sun Sat Middle School, and his work engaging students and teachers in the salient political issues of the day. He eagerly promoted patriotism from the time of the May Fourth Movement in 1919, and campaigned fervently against Japanese aggression, both as an activist and a government agent. “For more than a decade, he resolutely led the work against Japan,” the official record said. “He was a fearless martyr.”