There’s a little bit of Macao in Italy’s Trentino region. You’ll find it in a forest-fringed meadow tucked between towering mountains. This landscape couldn’t be more of a contrast to the highly urbanised Special Administrative Region (SAR), lending an air of intrigue to what the Macanese artist and architect Carlos Marreiros describes as his unlikely “portal” connecting the two places.

The Val di Sella’s Arte Sella is an internationally acclaimed open-air art museum. Its sculptural installations – including one designed by Marreiros – are a far cry from the coddled pieces displayed in conventional galleries. Here, Mother Nature lends a hand: exposure to sun, snow, wind and rain make Arte Sella’s exhibits change with the seasons – a concept that’s central to the museum’s philosophy.

The valley is home to works from many illustrious names from around the world, including the the German environmental artist Nils-Udo, the South Korean sculptor Lee Jaehyo, and Italy’s Michelangelo Pistoletto, a radical proponent of Arte Povera.

Macao’s Marreiros and Hong Kong’s Rocco Yim (the estimable architect behind Macao’s StarWorld Hotel and Guangdong Museum) were the first Arte Sella contributors from their respective SARs. The pair were invited to design sculptures for Arte Sella’s permanent exhibition in 2019; Yim unveiled his in September 2022, Marreiros’ was revealed a year later.

“It was something very special to be invited, I felt honoured,” Marreiros, 68, tells Macao magazine. The architect, who heads Marreiros Architectural Atelier as well as a culture centre, also holds a Portuguese passport. There’s just one other Portuguese artist with work in Arte Sella, he says – Eduardo Souto de Moura, winner of the 2011 Pritzker Prize (considered the highest international award for architects).

A landscape of giants

When Marreiros first visited Arte Sella in late 2019, the drama and scale of northern Italy struck him intensely. He was moved by its raw, majestic beauty, but also by cultural traditions embedded within its mountainous terrain. “This is a place of giants,” he explains. “Not literally, but in the folklore of people who have lived here. Seeing those massive mountains, I couldn’t help but imagine them.”

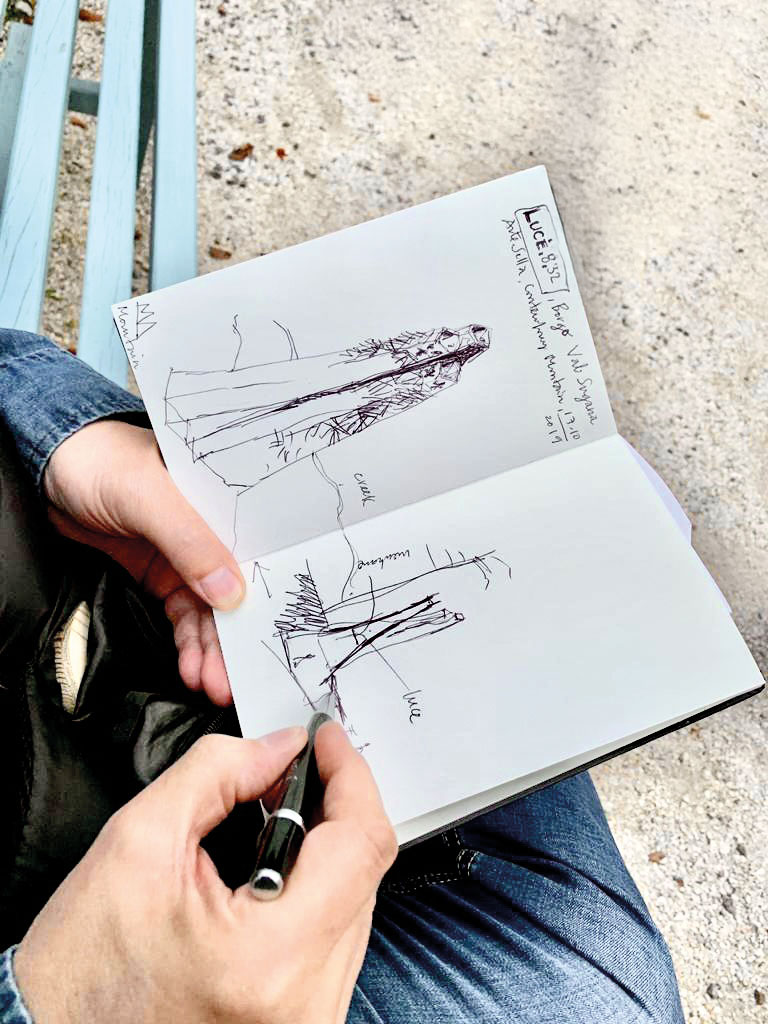

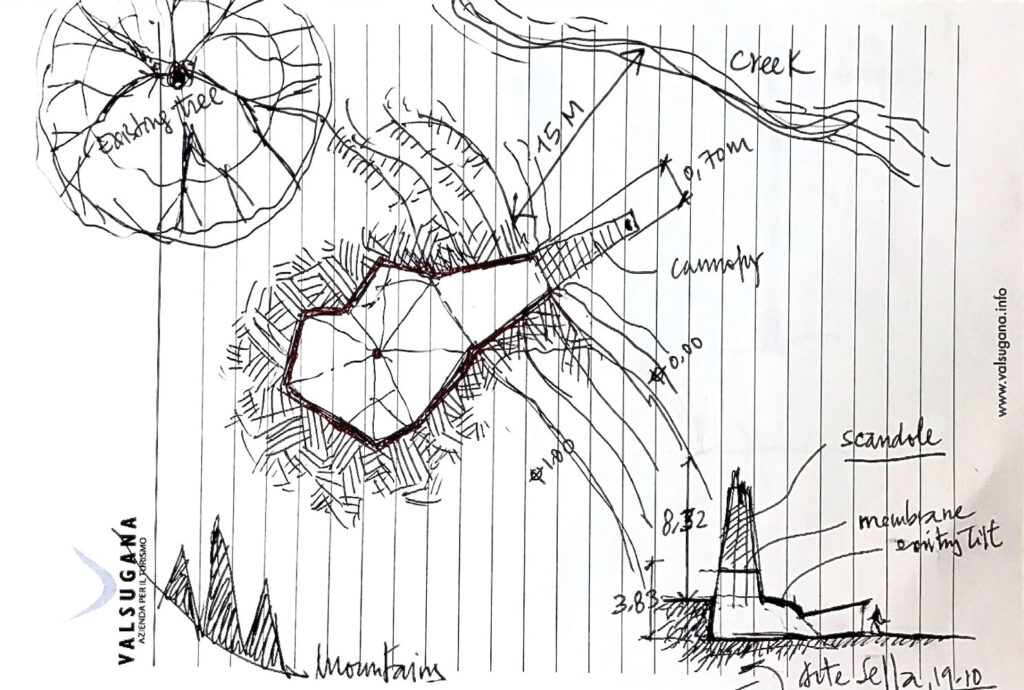

Marreiros spent several happy, wholesome days at a house within the Arte Sella grounds, picking mushrooms and eating hearty meals prepared by a chef using locally sourced ingredients. He collected leaves, made countless sketches of his designated site, and recalls feeling instantly inspired. He told himself: “I must create something very organic, something deeply connected to this environment, using materials provided by the mountains themselves.”

‘It just felt magical’

It didn’t take long for Marreiros to decide what his sculpture would look like from the outside. Tall and jagged, made of local larch wood. When freshly milled, this wood is a light brown tinged with red (like a blushing cheek, the architect describes), but it weathers into a shimmery, silvery grey. A similar colour to the sheer rock faces surrounding Arte Sella.

The sculpture’s interior was harder to settle on. Marreiros searched his memory bank for inspiration, and came up with something as far from Italy’s alps as imaginable: the 17th-century cisterns of Macao’s Monte Forte. The ‘monte’, for the record, is not a mountain, but a 52-metre-high hill (for comparison’s sake, Trentino’s highest peak stands at almost 3,770 metres). It’s also very urban. Located within Macao’s historic old town, the fortress was the city’s principal military defense structure between the 1620s and 1960s. It’s now the site of the Macao Museum.

Marreiros spent a lot of time around Monte Forte growing up; his grandfather had a house there. While the fortress’ centuries-old cisterns had once been essential for storing rainwater, ensuring a reliable water supply during sieges or periods of isolation, to Marreiros and his friends, they were a subterranean playground. “We discovered all the secret entrances and exits,” he remembers. “Even when the fortress was locked at night, we could still get in.”

The drainage ducts were built out of massive granite blocks, Marreiros says. These tunnels – no longer accessible – were about 1.5 metres by 1.5 metres, the perfect size for 12-year-olds to scamper around in, playing tricks on each other. But what the young Marreiros loved best was the way light behaved within them. Filled with quartz, the granite caused his torch beam to fracture and scatter. Its light would bounce around the space, almost like a kaleidoscope.

“At that time, we couldn’t rationalise what was happening because it just felt magical,” the architect says. “This memory stayed with me throughout my life.”

Marreiros wanted to recreate that sensation for people stepping inside his Arte Sella sculpture. Rather than line it with granite and provide torches, he left gaps between the structure’s wooden panels that allow slivers of sunlight to enter. These create a dappled, disco ball effect within the installation’s interior. Marreiros named his creation “Fragments of Light”.

“So, the exterior of my installation was designed to mimic the mountains, rocks, and cliffs, with a very organic structure,” he says. “The interior was inspired by my teenage memories in the granite tunnels of Monte Forte.” A portal between Italy and Macao indeed.

Representing Macao on the international stage

Of course, as a Macanese, Marreiros is no stranger to cultural intersections. Raised in Macao by a family proud of both their Chinese and Portuguese heritage, he later studied architecture in Lisbon, Portugal, where he also immersed himself in the history of Chinese civilization. Though Marreiros speaks Chinese, he cannot read it – so he revelled in Europe’s libraries, poring over books that examined the very culture he had grown up in.

These two worlds’ dual influence is evident across Marreiros’ creative oeuvre. “My entire artistic production is hybrid, because I am hybrid,” he says. For his Arte Sella piece, he consulted a Feng Shui master, ensuring that the structure aligned with ancient Chinese principles of design. Its south-facing opening, proximity to a stream and the mountain at its back are all auspicious elements promoting a natural flow of energy, or qi.

An architect by profession, Marreiros has been a multidisciplinary artist for even longer. His first exhibition of drawings, paintings and etchings was held in Macao in 1976, just before he left for Portugal, and over the years he’s expanded into sculpture and installations, all while maintaining his own architecture practice. Marreiros’ art has been exhibited in Asia and Europe, and he represented Macao at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

The architect, who worked as a civil servant in Macao’s government in the 1980s and early 1990s, believes very strongly in the importance of cultural heritage. During his tenure as president of Macao’s Cultural Institute, he spearheaded efforts to to help establish regulations to protect the city’s unique fabric. He also co-founded the Círculo dos Amigos da Cultura de Macau (‘Circle of Friends of Culture of Macao’ in English), a group that promotes contemporary art and heritage preservation. Now, Marreiros serves as president of Albergue da Santa Casa da Misericórdia, a creative hub housed in a century-old yellow complex. That’s where he office is, its walls practically papered with his drawings. “Unfortunately, these days, I paint less, but I still draw a lot,” he says. “Every day, I draw.”

Through the many different strands of his work, Marreiros helps keep his hometown’s cultural and urban heritage alive. Part of that is representing it on the global stage. His installation at Arte Sella joins sculptures by some of the world’s most important artists, serving as a reminder that Macao’s unique voice has a place in international artistic dialogue.