PHOTOS António Sanmarful and courtesy of Academia Jao Tsung‑I

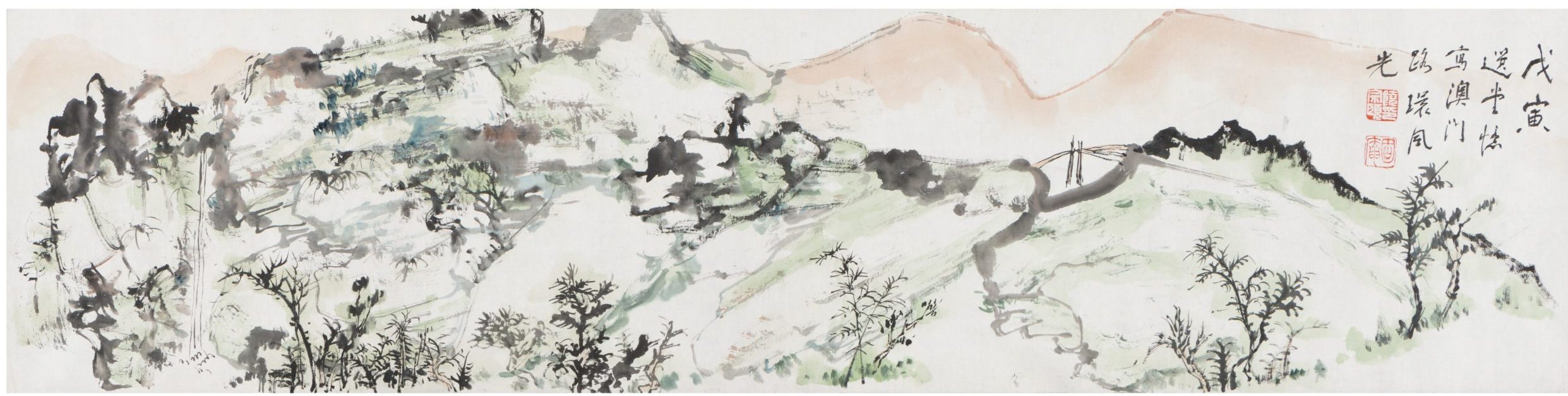

Academia Jao Tsung‑I, opened in August 2015 and houses 400 paintings and 75 artworks.

An academy in Macao remembers a “treasure of the nation”: Professor Jao Tsung ‑I, one of the greatest Chinese scholars of the 20th century, who passed away in February this year at the age of 100.

In August 2015, Professor Jao himself attended the opening of Academia Jao Tsung ‑I, located in a heritage building on Avenida do Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida, just a few doors from the Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC) in Tap Seac Square.

It houses 400 paintings and 75 artworks by the professor which he personally donated to the Macao government. A permanent exhibition of his paintings and calligraphies is open to the public. “He was given the title of ‘treasure of the nation’ by his fellow scholars for his achievements in research, literature, and arts. Very few people combined his skill in painting with his depth and breadth of scholarship,” said Chio Ut Hong, a senior official in the Division of Research and Publications of the IC. The professor also had deep links with Macao.

Academia Jao Tsung‑I, opened in August 2015 and houses 400 paintings and 75 artworks.

When the University of East Asia was established in the city in 1981, Jao was invited on as a visiting professor and served as chair professor at the School of Arts. He left the university in 1987, but his time there – particularly in founding the Department of Chinese Literature and History for the graduate school in 1984 – left its mark.

So in 2004, the university, now known as the University of Macau, awarded him an honorary degree of Doctor of Humanities and the title of Honorary Professor. He also served as an adviser to archaeological studies of cultural relics in the city, including the excavation of a site at Hac Sa Beach in Coloane in 2006.

In 2011, he donated 30 calligraphies and paintings to the permanent collection of the Macao Museum of Art. Two years later, he gifted 159 art pieces and academic works to the Macao government.

His namesake Academia Jao Tsung ‑I is housed in a former residential building constructed in 1921. This neo‑‑classical structure, with its elegant columns and refined details, was inscribed on the list of protected heritage sites in the city in 1984. Locating the academy here fulfils the government aim to transform heritage premises into cultural facilities, allowing visitors to enjoy the great scholar’s works within one of Macao’s architectural jewels.

Young prodigy

Jao was born in 1917 into a wealthy family in Chaozhou in the north of Guangdong province. His father was both a successful businessman and an accomplished scholar. In his hometown, he built a library with more than 100,000 books.

In his later years, Jao reminisced about his childhood: “When I was small, I spent the whole day immersed in ancient books and paintings in the library. I was completely absorbed; I never felt lonely. From an early age, I had this aptitude. No matter what was going on outside in the world, I would concentrate on what I was doing. Using all your concentration – then you could do something well.”

It proved an ideal environment to cultivate a scholar. Under the guidance of his father, Jao studied poetry, ancient books, and other scholarly pursuits. Then he studied painting with a master and learned the basis of his art.

At the age of 13, he entered the Jinshan Middle School in Guangdong but stayed only one year because he found the courses too superficial. He preferred to study on his own, guided by his father’s extensive book collection. Then when he was 15, his father passed away. Jao took over the Chaozhou Arts Magazine, which his father had edited, and published articles in the Lingnan Scholars Newspaper. His reputation began to spread.

In 1938, he was accepted as a researcher at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou. The focus of his study was ancient books and classical Chinese culture. Later that year, after the Japanese invasion, the university moved to Dengjiang in Yunnan province in southwest China. Suffering from ill-health, Jao moved to Hong Kong, where he remained until the city fell to the Japanese in December 1941. During those years, he researched oracle bones and read a large number of historical books.

In 1949, Jao returned to Hong Kong for a second time and made it his permanent home. He flourished in the city because it provided freedom for scholarly work and was well managed. The scope of his study was very broad; it included ancient history, oracle bone inscriptions and Chu Ci, an anthology of Chinese poetry with roots in the Warring States period (475–221BC).

In 1952, he joined New Asia College in Hong Kong, where he taught poetry classics, Chu Ci and literary criticism. From the 1960s onwards, he travelled widely, accepting positions at universities across the globe.

A gifted polymath

An erudite scholar, Jao was well known for the depth and breadth of his scholarly pursuits, which included classical studies, oracular bone inscriptions, archaeology, epigraphy, bamboo and silk texts, bibliography, regional folklore studies, the study of poetry and ci, historiography, palaeography, religious studies, art history, music, and literature.

More than mere interests, he pursued each topic with distinction and often ground-breaking research: he initiated research on the Dunhuang manuscripts, turning it into a global discipline; he provided the first translation of the Babylonian creation epic Enûma Eliš into Chinese; and he conducted the first comparative study of oracle bone inscriptions, the earliest known form of Chinese writing which dates back to the late 2nd millennium BC.

In addition to his academic pursuits, Jao explored a variety of complementary creative avenues, often receiving recognition for his achievements. His works of Chinese calligraphy and painting boast a unique character – he even created his own calligraphic style, Jao’s Clerical Script, that is held in particularly high regard. An installation at Ngong Ping on Lantau Island took his calligraphic work to a monumental scale with 38 towering steles that form the Wisdom Path, now an important local landmark.

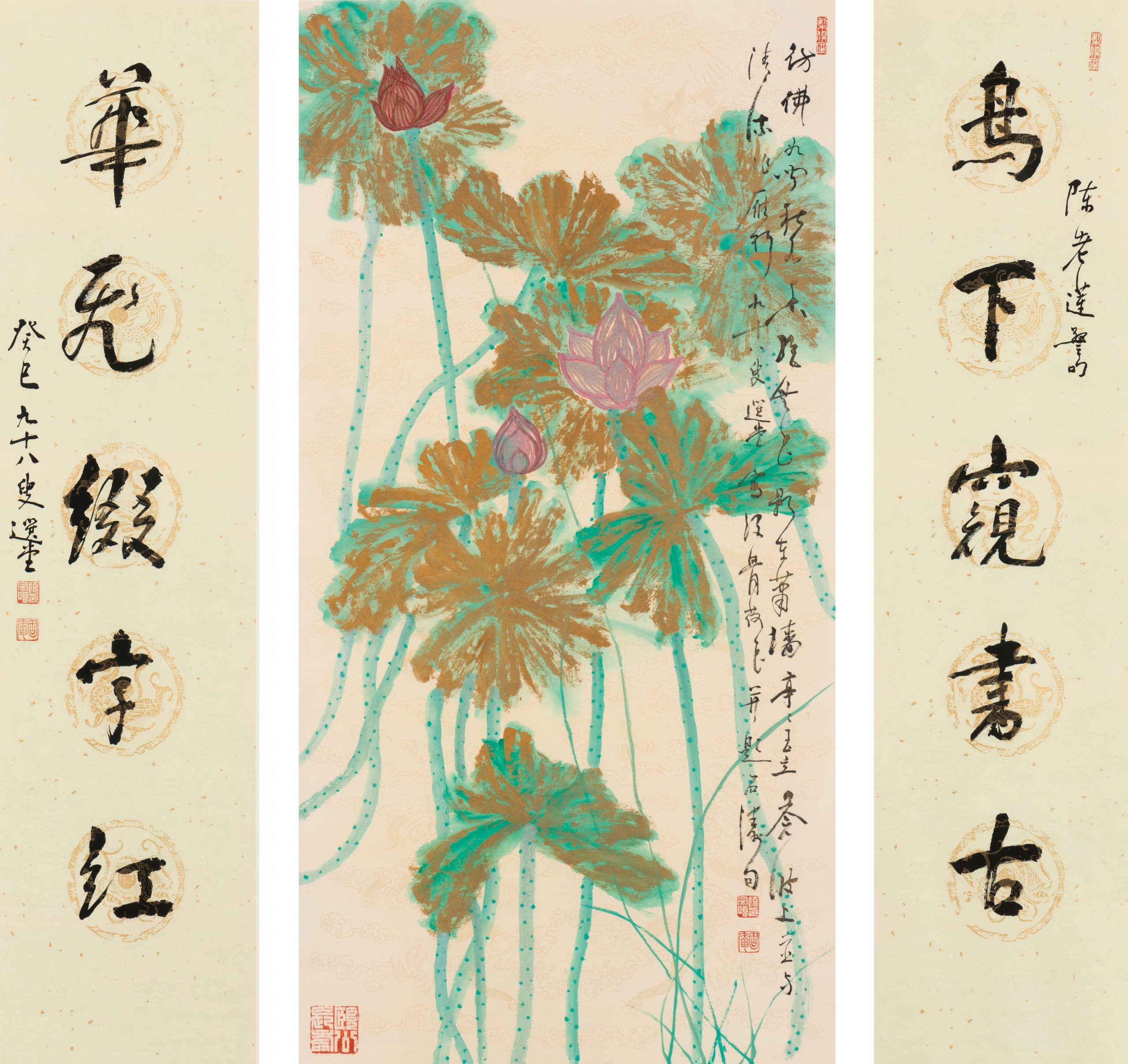

Through intense study, he developed a command of the painting techniques of the Four Monks of the Late Ming and mastered those of artists such as Fu Qingzhu and Chen Laolian. Jao even learned to play the Qin, an ancient string instrument of China and is well known as a writer of the ancient Chinese literary genres. He received numerous awards and honours from academic institutions in France, Russia, Japan, Australia, and mainland China, as well as Hong Kong and Macao. In 2011, the Purple Mountain Observatory in Nanjing named a minor planet after him: Jao Tsung ‑I Star, or simply 10017. Through an academic career of 80 years, he published over 100 academic and artistic monographs and nearly 1,000 academic papers.

Buddhist influence

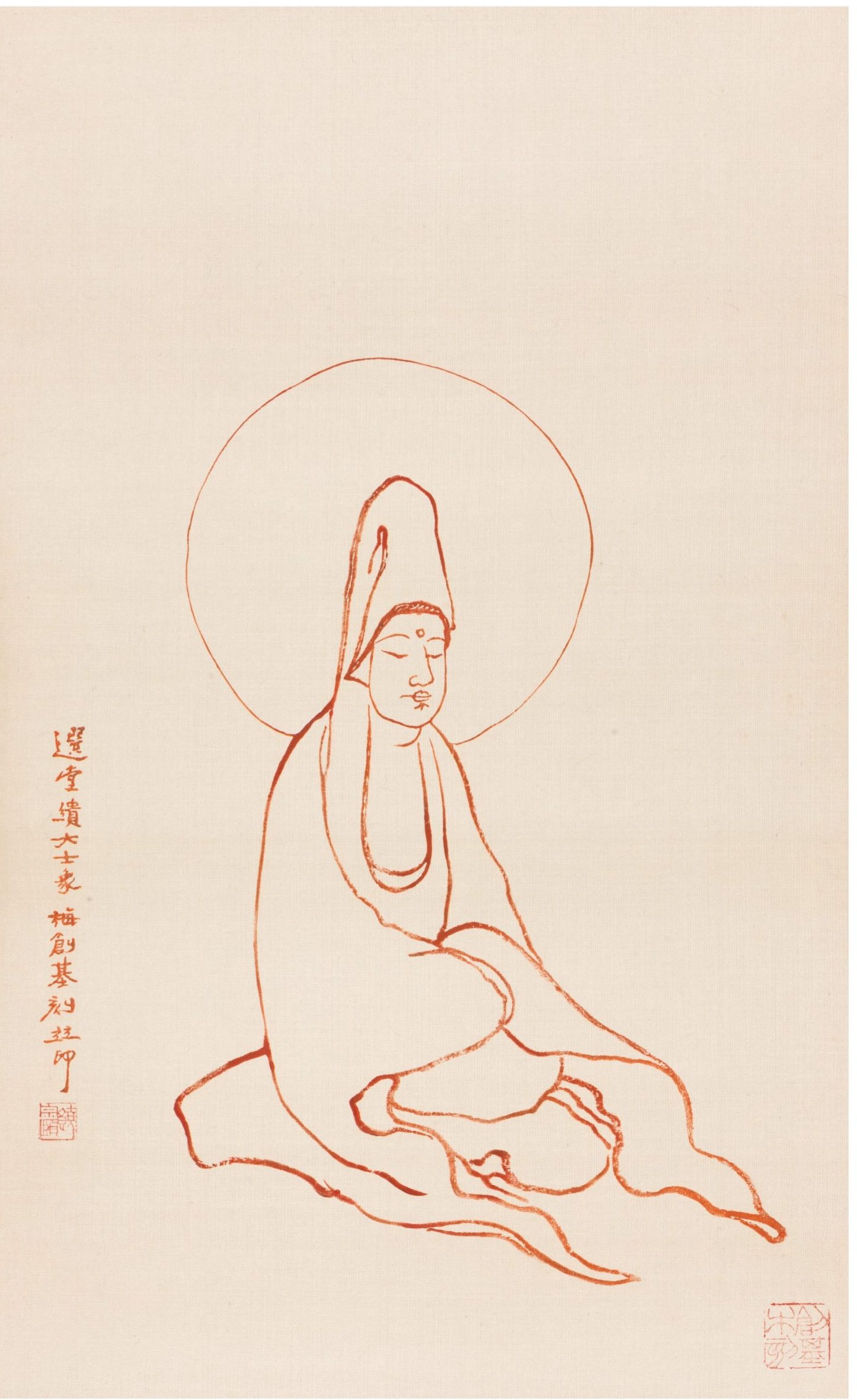

Jao began reading Buddhist scriptures as a child, teachings that would greatly influence his approach to life and his work. “He loved to paint the lotus flower, which is a symbol of Buddhism. The flower flourishes even in mud and dirt. Goodness can grow even in a difficult surrounding,” Chio explained.

“Macao is called the ‘blessed land of the lotus’,” she noted, adding that “it is known that Professor Jao Tsung ‑I was given his name by his father Rao E, with an expectation that he would learn from Zhou Dunyi, an erudite scholar of the Song dynasty (960–1279AD) and author of the famous essay On the Love of the Lotus. The essay has given an immortal image of gentleman to the lotus, featuring a famous sentence literally meaning ‘It comes out of mud yet is not contaminated; it is washed by waving water yet unaffectedly graceful.’ One may say that Professor Jao has been closely connected with the lotus since his birth.”

Beyond his affection for lotuses, Jao produced many artworks based on his comprehensive research of Dunhuang art, a collection of some of the finest Buddhist art over a span of 1,000 years. The Wisdom Path, arranged in a twisting infinity symbol, contains Jao’s calligraphy of the Heart Sutra, one of the world’s best ‑known prayers revered by Buddhists, Taoists, and Confucians alike.

He studied Zen Buddhism, and regarded the revival of Zen paintings with the keen eye of a scholar of that history. So much of what he studied in his varied scholarly pursuits became incorporated into his art, a reflection of the “dual synthesis of scholarship and art” which he advocated and Academia Jao Tsung ‑I embraces.

According to the introduction of Wong King Keung, one of the three founders of the University of East Asia, “[Jao] impressed people with his personality. His demand for the standard of scholarship was very high. He was pleasant, yet serious. If you asked him an academic question, he would respond rigorously and empirically.”

The professor found the correct balance between work, health and rest, enabling him to live a long and productive life. Chio said that, during his visit to Macao for the opening of the academy in 2015, then 98 ‑year‑old Jao was healthy and clear-minded.

Role of Academia Jao Tsung ‑I

The academy averages around 1,000 visitors a month, with a roughly even split between local people and tourists, said Chio.

“This is a cultural area, with many historical buildings. This building is a symbol of the Sino‑‑Western combination that is Macao: the external structure is Western but the inside has many Chinese features,” she noted. “Macao has a strong tradition of Chinese culture, it is close to people. It is good to spread Chinese traditional culture among local people. They like to use this space.”

The academy contains a library with writings of, and catalogues about, the professor, in addition to the permanent collection of his artworks. It is also a venue for cultural activities, with the library, a room for temporary exhibitions and an auditorium, that local associations can apply to use. Like Jao himself, the academy endeavours to use its resources to promulgate Chinese culture and arts, and promote academic exchange in the field of sinology.