The Mandarin’s House in Macao is one of the city’s architectural and cultural marvels, and its intellectual owner has played a key role in the revival of modern China.

Despite its small size, Macao is packed with historical and cultural treasures. In recognition of its unique tapestry, UNESCO designated Macao’s Historic Centre as a World Heritage Site in 2005. Among this compact cluster of streets and buildings is the Mandarin’s House. This ancestral mansion is architecturally outstanding and its painstaking restoration took nearly nine years. It is not only widely regarded as one of the best remaining examples of the Lingnan (south China) design style but it was also the home of one of China’s most important intellectuals, Zheng Guanying.

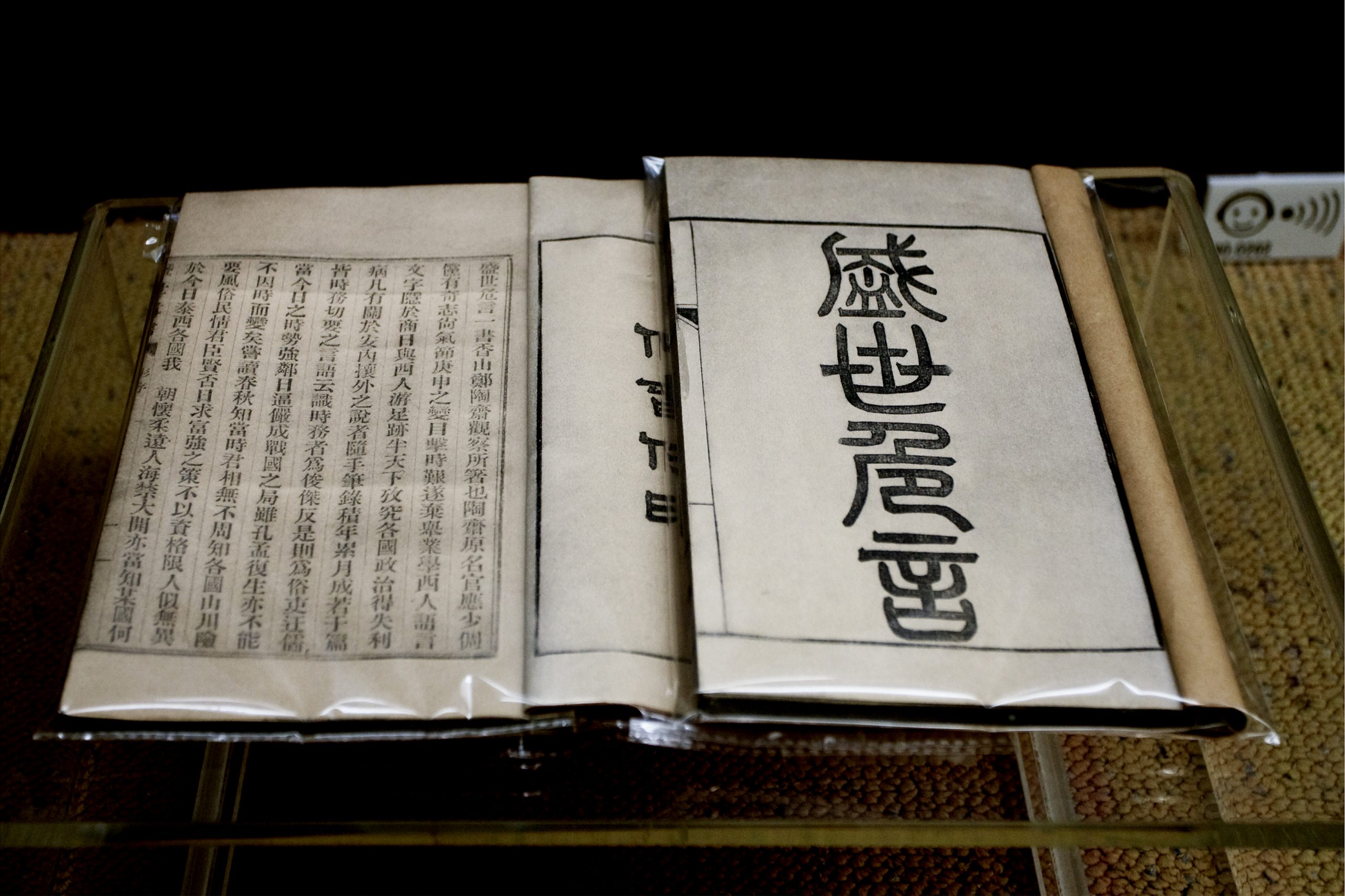

Zheng was a senior Chinese government official, a successful businessman and also a passionate advocate of China’s modernisation and reform. His hugely influential work Words of Warning to an Affluent Age was actually written in the Mandarin’s House. Its well-honed and passionate arguments attracted the attention of the Chinese emperor as well as the future founders of both the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen, and the People’s Republic of China’s Mao Zedong. It was a book of such outstanding brilliance that it appealed to both rulers and revolutionaries.

Not surprisingly, the Mandarin’s House has become one of Macao’s most popular tourist sites, and prior to the pandemic, it had welcomed more than 116,000 visitors in 2019. With rooms and courtyards covering 4,000 square metres, this imposing private mansion gives a sense of the grandeur of a bygone age. The house offered Zheng a haven for reflection and writing, in the middle of a public life full of challenges and setbacks.

The mansion was built in 1869 by Zheng Guanying’s father Zheng Wenrui – a teacher, scholar, intellectual and collector of old books. The house itself was one of the largest private residences in Macao at that time, with a complex of courtyards extending more than 120 metres along the street. The Zheng family lived in two enclosed courtyards – one was two stories high, the other three. There were also gardens and a one-storey servant quarters.

The Zheng family came from the Zhongshan (then known as Xiangshan) prefecture, just over the border from Macao in the mainland’s Guangdong province. Zhongshan was the most open to the outside world, and during the late Qing Dynasty and early Republican period, it produced many distinguished industrialists, entrepreneurs, writers and diplomats. The most famous was Sun Yat-sen, another was Zheng Guanying.

Macao, which at the time was under Portuguese administration, was the favoured destination of the rich and the intellectual elite of Zhongshan. It was one of the most modern cities in the region.

Zheng was born on 24 July 1842 in Yongmo township of Sanxiang in Zhongshan. He spent his early years in his hometown, moving to Macao when he was seven or eight.

Following the First Opium War which ended in 1842, the ports of Shanghai and Guangzhou were forced open to foreign commerce. Those who became part of a new business sector – importing foreign products and exporting Chinese ones – made fortunes. One of Zheng’s uncles and one of his cousins had gone to Shanghai to work in this field, as compradors, or middlemen, for foreign companies.

Zheng Wenrui decided that his son would have a better future in business than as a scholar. So, in 1858, when Guanying was only 16, his father sent him to Shanghai to live with his uncle and work with him in a foreign trading company. The young man sat in the office of his uncle, listening and learning, and beginning his English studies.

In 1859, thanks to the introduction of a relative, he went to work in Butterfield & Swire, one of the biggest British trading firms at that time. He eventually established branches of Butterfield and Swire in Jiangxi province and Fuzhou and invested in a new joint-venture shipping company.

Founding China Merchants

After nine years, Zheng went into the tea business on his own account and became a partner in the Gongzheng Shipping company. In 1872, he became the superintendent of a salt bureau in Jiangsu province. The next year he became one of the founding shareholders of Swire Shipping and a shareholder in China Merchants Shipping (CMS), established by the Qing government to challenge foreign firms that dominated China’s import and export business. Today the firm is an international conglomerate with its headquarters in Hong Kong.

In 1874, Zheng accepted the post of general manager of Swire Shipping, setting up branches and financial offices in ports on the Yangtze river. From then on, the firm’s business boomed. In addition, he diversified his personal investments. From being a comprador, he had become an independent capitalist. He had a close relationship with Li Hongzhang and other leaders of China’s Self-Strengthening Movement, a reformist group.

There were few men in China with Zheng’s curriculum vitae. He had worked at a high level in one of the foreign trading firms and knew its management methods, accounting and personnel management style. CMS was established as a model, using Western methods and management techniques. It needed people like Zheng to run it.

Wu Zhiliang, President of the Macao Foundation, argues that this time in Shanghai was vital for Zheng: “His experience as a comprador in Shanghai deepened his understanding of the political, economic and social situation of modern China, which was then plagued by domestic instabilities and foreign invasions.”

In 1880, Emperor Guangxu appointed Zheng to manage both the Shanghai Machinery and Weaving Bureau and the Shanghai Telegraph Bureau. The same year, Zheng completed On Change, a compilation of 36 essays on political and social reform and his advocacy of market competition. He aimed to reach decision-makers at the highest level of the government, including the Qing court.

Zheng’s essays advocated the study of Western knowledge and methods, and the translation into Chinese of Western books on science, technology, industry and the military. It also proposed the introduction of machine production, the development of industry and commerce, and the boosting of private investment in industry, including mining, shipbuilding and railways.

He expressed anger at a tax system that unfairly favoured foreign companies in China over domestic firms. He also proposed political reform and constitutional government. In 1882, he left the Swire company and turned his energy to CMS. Profits improved and in 1883, Li Hongzhang promoted him to chief executive of CMS.

During the Sino-French War (1884-85), Zheng was sent by the Chinese government to Southeast Asia (today’s Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand) to collect intelligence and encourage local people to oppose the French.

When the French attacked Taiwan, he went to Hong Kong and chartered a ship to carry troops, grain and ammunition to Taiwan. His book Travels to the South is a memoir of this journey. He wrote another book Diaries of Seafaring about tours of Southeast Asia and Southern China.

Within the traditional Confucian system, officials looked down on merchants. Zheng therefore had to obtain an official rank to improve his status and gain a larger audience for his ideas. Initially he did this, like other wealthy merchants, by buying official titles. But later the government awarded him further titles because of his contributions to disaster relief and to public services.

Entrepreneur turns activist

In 1885, financial problems plagued his companies. Zheng was exhausted by these difficulties and his family urged him to retire. He took their advice and moved back to Macao, where Zheng resumed living in the Mandarin’s House. He developed and enriched the ideas expressed in On Change. Freed from daily management and political infighting, he was able to concentrate on writing and arranging his thoughts in a more systematic manner.

The new book covered politics, economics, diplomacy, culture and military affairs and reflected what he had learnt during more than three decades in government and business. In 1894, he published the first five chapters of what became his most famous book: Words of Warning in Times of Prosperity. He changed the title from On Change to give it a greater sense of urgency. The title was ironic since the 1890s was not at all an era of prosperity for the Qing empire.

In 1894, China became embroiled in a war with Japan that resulted in humiliating defeat and the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, under which China ceded the province of Taiwan and other territories. The defeat created public protest against the Qing government and China’s treatment by foreign imperialists.

Zheng’s book summarised his experiences as a businessman and as an observer of a declining dynasty confronted by aggressive foreign powers equipped with advanced weapons, technology and political systems. One year later in 1895, Zheng published an additional 14 chapters and, in 1900, a revised eight-chapter version.

Zheng’s book captured the spirit of his time and described the feelings of thousands of intellectuals. It was a reformist’s bible, an indictment of a great country in decay and a programme of how to save it – a constitutional monarchy, a new examination and education system, a dense network of roads, railways and telegraph, and the study of western science, medicine and electronics.

It analysed the close relation between a nation’s military strength and its commercial prowess. The book went through more than 20 editions and sold more copies than any other title during that period.

He achieved his objective of being read by the most powerful people in the land. Emperor Guangxu read it in 1895 and liked it so much that he ordered 2,000 copies to be distributed to his ministers and other high officials. It helped to inspire a sweeping programme of reforms – including many of those advocated in the book – in June 1898.

The book’s readers also included Kang You-wei and Liang Qi-chao, two of the leaders of the 1898 reform, who only escaped execution by fleeing to Japan.This proved to be the last attempt by the Qing government to reform itself.

On 11 September 1898, the conservative Empress Dowager Cixi Taihou organised a coup d’etat, forced Emperor Guangxu into seclusion and executed six of the chief advocates of reform. It became known as the Hundred Days’ Reform.

Despite this setback, Zheng continued to hold important positions in China, including in railway and shipping companies. He divided his time between Guangdong and Shanghai, working as a businessman and writer.

Like most Chinese people, he rejoiced in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty in 1911. But he was disappointed that the revolution led to warlords taking power in many provinces of China. So he devoted his final years to education. He was chairman of a public school founded by China Merchant Steamship (CMS) in Shanghai and honorary director of the Shanghai Commercial Middle School. In April 1921, he retired as chairman of the CMS school and died in May 1922 in Shanghai. A year later, his coffin was taken to Macao for burial.

He left behind written works totalling 1.5 million characters. Perhaps his most lasting legacy was his impact on two of 20th-century China’s political giants: Sun Yat-sen and Mao Zedong. Sun adopted many of Zheng’s ideas in his plans for a modern Chinese republic after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Mao Zedong, founder of the People’s Republic of China, wrote in 1936: “I very much liked this book. The author was an old reformist who believed that the weakness of China was due to the fact that it did not have the instruments of the West – railways, telephones, telegraphs and steamships.” After the 1949 revolution, Mao followed Zheng’s advice and made the rapid industrialisation and modernisation of China one of his priorities, a policy carried through to the present day.

Changing fortunes

With six wives and several concubines, Zheng left behind a large family. Few remained in Macao; most moved to other parts of China or abroad. For years, the house was rented out as cheap accommodation for dozens of families, despite an inadequate infrastructure. It had no modern toilets and each morning a man arrived with a cart to remove the human waste. Running water was in short supply and families had to share kitchens.

The number of residents peaked during World War II, when Macao’s population tripled to 450,000, due to refugees fleeing the mainland and Hong Kong.

From 1991, Macao’s Portuguese administration began to negotiate the purchase of the house from the developer, but without success. In 1992, the Mandarin’s House was listed as a “Building of Architectural Interest” under Macao’s Heritage Law. During this process, many valuable items were stolen from the house.

Following Macao’s return to Chinese administration, the Macao government finally took over the badly damaged structure in 2001. Decades of disrepair and a fire demanded a painstaking restoration process that allowed the Mandarin’s House to reopen its doors in 2010, five years after it had been included in UNESCO’s list of sites in the “Historic Centre of Macao”.

The Macao Foundation’s Wu says the Zheng Guanying and the Mandarin’s House illustrates the interweaving of Macao’s history with that of the rest of China. “The history of Macao is a miniature of Chinese modern and contemporary history. Many historic incidents in Macao were closely related to certain major segments in Chinese modern history. Many important historic figures left their footprints in Macao during this process. If we study deeply the important functions of these figures in the history of Macao and China, the content of Macao’s history can be enriched, and the importance of Macao’s history can be highlighted.”

The storied history of the Mandarin’s House is a tale of lost grandeur, neglect and decay followed by a long-awaited rebirth – themes which, as Zheng Guanying would no doubt recognise, reflect China’s own path to revival.