TEXT João Guedes

Few people know of the close connection between Macao and the Bordalo Pinheiro family of late 19th century Portugal. Nor do they know how local techniques influenced the popular Caldas da Rainha porcelain from Western central Portugal, including figurines of the iconic everyman Zé Povinho, that remains a hallmark of Portuguese national tourism to this day.

The Bordalo family’s connection to Macao began when the patriarch, Manuel Maria Bordalo Pinheiro, was chosen to sculpt two highly symbolic monuments for Macao: the bust of the poet Luís de Camões and the monument to commemorate the Portuguese victory against the Dutch invaders on the 24th June 1622.

The Camões bust was a personal initiative of the businessman Lourenço Marques, owner of the Garden House and of the garden where the poet’s grotto is found. The job of overseeing the commission went to Carlos José Caldeira, former director of the National Printing Office of Macao, who had meanwhile returned to Lisbon. Manuel Maria fashioned its gesso model after the Camões portrait bust depicted in the “Discourses” of Manuel Severim de Faria, printed in Évora in 1624. The bust replaced one that had stood in the Camões Grotto since 1840, a piece crudely crafted “in bronze limestone or clay by Chinese artists.”

The Victory Monument was meant to replace the wooden cross that then marked the site (now the Victory Garden) where a cannonball shot from the Monte Fortress had found its mark, exploding the Dutch troops’ gunpowder wagons and deciding the battle in favour of the Portuguese.

While the replacement of the Camões bust was uncontroversial, replacing the Victory Monument proved quite the opposite. Foreign citizens were said to have raised objections to the initiative, claiming that it offended them. Given the nature of the monument, such complaints likely came from citizens of the Netherlands or representatives of that country in Macao. The monument thus remained in a Loyal Senate warehouse for eight years before it was finally unveiled by Governor António Sérgio de Sousa on the 26th March 1871.

Manuel Maria remains a peerless figure in the art history of Portugal, standing out as one of the most expressive representatives of Romantic art. In addition to the monuments, he left behind a large number of historical and anecdotal paintings, many of them earning prizes in exhibitions abroad. He simultaneously directed illustrated periodicals as well as the first fine arts journal, and worked with the great historian Alexandre Herculano on founding the magazine Panorama.

The family legacy

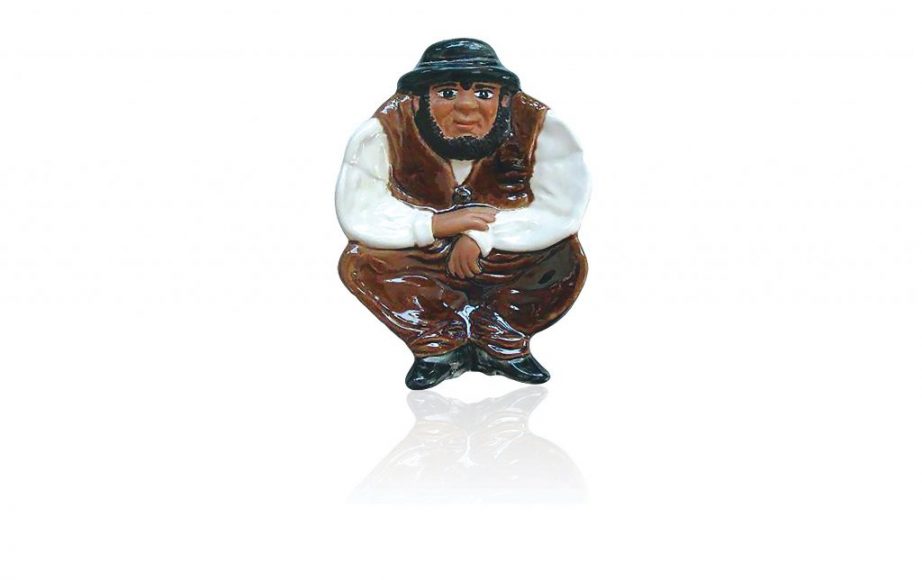

The Bordalo Pinheiro children, eight sons and daughters, were also directly or indirectly linked to the arts. The fourth son, Columbano, continued his father’s work in the area of painting, producing notable portraits of some of Portugal’s leading contemporary figures. But the most well known of the siblings today is his brother Rafael. He was a pioneer designer of the artistic poster as well as a draughtsman, watercolourist, illustrator and decorator. Above all, Rafael was known as a caricaturist and ceramicist, as well as a teacher. He created the character known as Zé Povinho, who became a symbol of the Portuguese common people. The sisters are also said to have been closely linked to the arts. Although they never reached the heights of fame.

Only two of the eight brothers did not follow their father’s footsteps. Manuel was educated in medicine, following a military career, while Feliciano chose engineering but likewise joined the army. He would end up grounding the family’s entrepreneurial involvement in the resurgent pottery industry of Caldas da Rainha in central Portugal.

The Macao connection

Feliciano, an artillery captain, was mobilised to Macao, where he occupied the post of public works director for a few short months in 1875. His contribution to culture in Macao went beyond his responsibilities as head of public works, though. He actively took part in a diverse array of initiatives, mainly in the cultural and artistic domain. He thus benefited not only from the specific environment in which he lived, but also from a relative affluence which allowed the government to move forward with various projects, among them construction of the Conde de São Januário Hospital, a major project designed by António Alexandrino de Melo, one of the two architects (the other previous one was José Tomás de Aquino) who most impressively marked the 19th century.

During his service in Macao, the city enjoyed an exceptionally rich cultural environment. Cultural activity revolved around two poles, the Military Club and the Dom Pedro V Theatre, where the concerts and operatic works featured some of the leading performers of the age. Music and the arts in general were held particularly dear, with growing interest in collecting, especially classical Chinese porcelain and painting from diverse schools.

Among the most well known Chinese porcelain schools then highly valued in Macao was that of Shek Wan.

Shek Wan’s influence

The important ceramic production centre of Shek Wan is situated in the Foshan region between Macao and Guangdong. Ceramics produced there “are popularly themed and combine ornamental with natural forms, highlighting the mastery of ceramic firing technique, leaving areas of uncoloured clay enlivened by the glazed pigments.” That decorative technique emphasises ivory‑whites and various tones of blues, reds and greens. The school’s themes focused on popular imagery, particularly of Chinese legends and heroes.

The Shek Wan work then circulating in Macao did not go unnoticed by Feliciano Bordalo Pinheiro, who apparently made a personal trip to the region to learn the secrets of its manufacture.

Upon recognising the craft’s singularity, Feliciano likely realised that the porcelain industry of Caldas da Rainha, then much deteriorated, might gain some future viability through use of the Shek Wan technique. Although he was basically a businessman, Feliciano did have a certain artistic facet. The two sides of his character enabled him to accurately assess just how far the technical innovations of Shek Wan could be translated into economic success.

Upon recognising the craft’s singularity, Feliciano likely realised that the porcelain industry of Caldas da Rainha, then much deteriorated, might gain some future viability through use of the Shek Wan technique

Joining talents

Feliciano was sure of his entrepreneurial talent and he trusted the creative capacity of his brother Rafael. In 1884, Rafael had made yet another addition to his talents, becoming a ceramicist. “He began in April of that year at the Gomes Avelar factory in Caldas and soon opened his own facility, the Ceramics Factory of Caldas da Rainha financially backed by Feliciano, where he would give free rein to his creative power,” stated the great heritage researcher Irisalva Moita, a pioneer of industrial archaeology, who studied in depth the history of the Bordalos’s ceramic industry.

Feliciano invested 800 contos, an extraordinarily high sum at the time, to restore the ruined factory. He also provided his brother with technical details about the manufacture of Shek Wan porcelain, a role corroborated by Monsignor Manuel Teixeira, who stated: “it is clear that Feliciano took his chinoiseries to Portugal, which eventually inspired his brother Rafael!”

The story of the revived ceramic ware tradition in Caldas da Rainha owes a great deal to Feliciano Bordalo Pinheiro. Inspired by his time in Macao, his investment in Ceramics Factory of Caldas da Rainha gave rise to an industry that remains successful to this day. It also led Rafael to create the distinctive type of ceramic ware that is perennially linked to his name.