Veteran photographer preserves Macao’s history

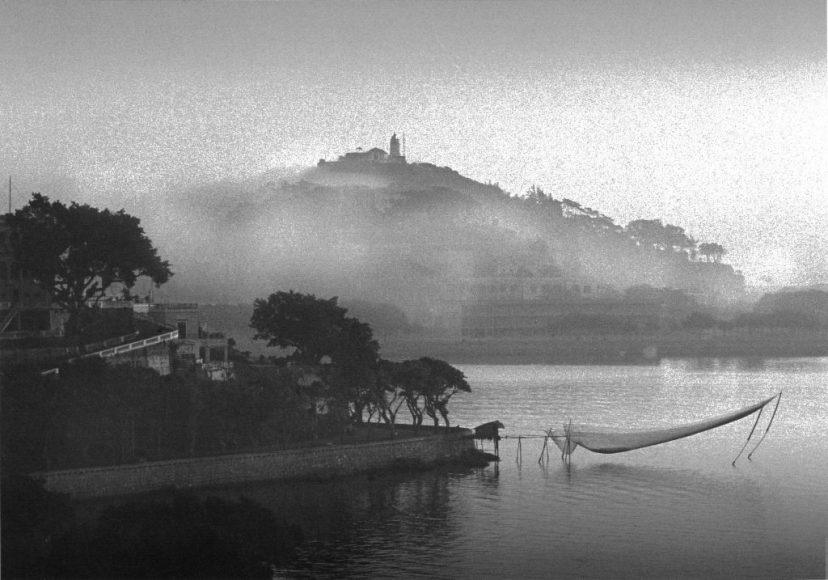

Behind a row of trees, junks float in Macao’s western harbour as the sun rises in a moment captured by veteran photographer Ou Ping in the 1960s. “I got up about five o’clock in the morning and waited for the sun to come up to catch the right moment,” recalls Ou, still spritely at 84. “You could not see such an image now. There are no more junks, and the shore is lined with skyscrapers.”

Back then, as he eagerly snapped photos of the local scenery and city life, Ou did not realise that he was also documenting history by recording images of Macao no longer seen today. The city has developed so quickly that in just the past 15 years, the landscape, both natural and man-made, has changed completely.

Born in 1932, Ou acquired his first camera in the 1960s and has been shooting images ever since. Most of his work features Macao, and in 2004, he donated the majority of his collection – between 2,000 and 3,000 photographs – to the Macao Museum of Art to ensure its preservation. Now, these images that tell the story of the city’s history are in good hands and accessible to the public. “I knew that one day I would leave this earth. My family would not look after the pictures so well, so I donated them to the museum. They have put on many exhibitions and will look after the pictures properly. I retain the copyright.”

Ou remains a keen and active photographer. He continues to document Macao’s major festivals as well as his voyages abroad to such international destinations like Central and Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia and Japan. A man of discipline, he rises each morning at 6 a.m. and goes for a 30-‑minute walk in his local park. He also takes a substantial nap after lunch. He does not smoke or drink. His passion for photography remains unwavering with the support of his wife.

Falling in love with the Macao of old

Ou was born in the mainland in 1932. His father was a civil servant for a brief period before training to become a Chinese doctor which he later practised in their native village.

During World War II, Ou was placed with relatives in neutral Macao, which was more stable and well-supplied than Japanese-occupied Guangdong province. He returned home after the war to complete his education before coming back to Macao in 1950. “My first job was as a teacher in a technical school teaching every subject.”

After a few years teaching, he went to work for San Yuan Dei, a small newspaper and predecessor to Macao Daily, where his role was also all-encompassing. When Macao Daily was established in August 1958, Ou joined the finance department as an accountant and rose to become chief of the department.

His love affair with photography began in the 1960s. “In those days, a camera was very expensive, a luxury. I joined friends who also had an interest, and we took photographs together. The best we could do was a second-hand camera. Developing film was expensive, too… the economy was not strong. Macao had no industry, only manual production. We took pictures of those making firecrackers and incense sticks and building ships. The scenery was very beautiful and there were no skyscrapers. Life was simple. People had street stalls and could make a living. The toys used by children were simple too. Everyone was happy.”

Because cameras were a novelty at that time, people were sometimes afraid and unwilling to have their images taken. Ou would introduce himself beforehand to his subjects to put them at ease.

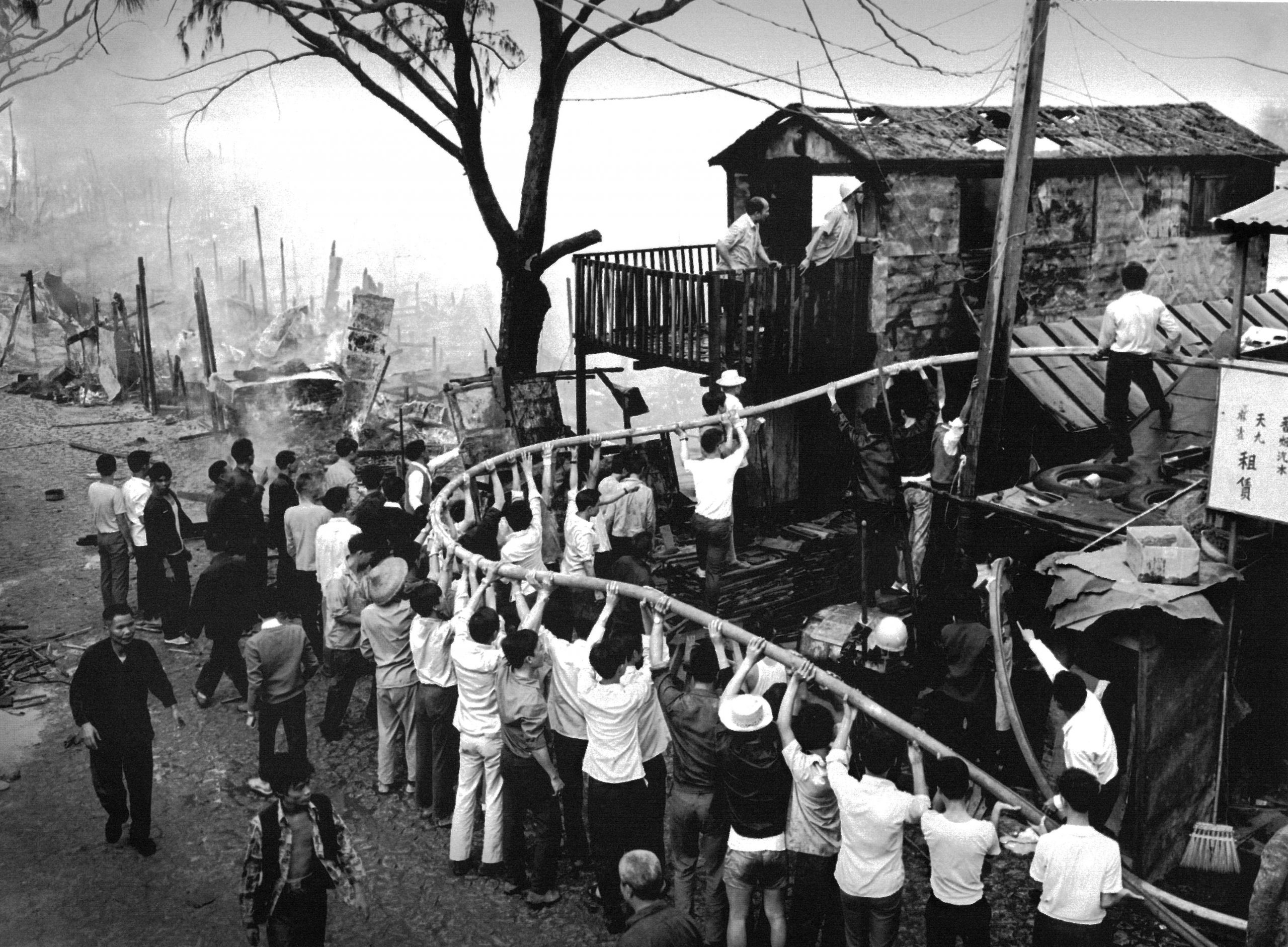

“While living conditions were difficult, personal relationships were good. Everyone wanted to help each other. People used to give rice and cooking oil to their neighbours in need.” He captured this sentiment in an image taken in 1972 of a fire in Fai Ji Gei. The still depicts everyone lining up to help fight the fire, holding the water hoses together. “Young and old, men and women are working together, while the firemen are closer to the flames. It is hard to imagine such a scene today. Have our lives become too precious? Or has our sense of security increased? Perhaps it would be beneficial if we were to feature such an image in our civics education classes.”

In those days, a camera was very expensive, a luxury. I joined friends who also had an interest, and we took photographs together. The best we could do was a second-hand camera

Ou Ping

With low-rise buildings forming the skyline and a small population, nature settings and scenery were more prominent in Macao and some of Ou’s favourite subjects. In an era of few motorcars, Ou went everywhere by bicycle, shooting junks boats and fishing boats and the sea’s many moods. Cleaner air and frequent fog back then provided optimal visual conditions for a photographer’s lens.

Ou and his friends established the Photographic Society of Macao (PSM) in January 1958, the first association of its kind in Macao. Ou eventually became its director and then chairman in 1969, a position he held for 16 years. He later became secretary-general and remains an active member today. Since the 1970s, the society has held exhibitions of its members’ work.

His photographic lens spread their wings

In the 1980s, China opened its doors to the outside world. This gave Ou and other PSM members the opportunity to explore the mainland’s diverse scenery, culture, and faces. Forming their own tour group, they visited Beijing, Nanjing, Shanghai, and Suzhou among others, with cameras in hand. “If you joined a regular tour, you spent only a short time at specific locations, not long enough to shoot good images.”

“We were allowed to take pictures but had to be careful. We could not shoot areas that were forbidden.” Upon entering the mainland, they had to leave a detailed record of the cameras and lenses they were carrying. Before they left the country, they also had to let officials see the developed film so that inappropriate or unapproved images could be cut. “That was how it was at the beginning. The door had just opened. We could shoot ordinary life, but we could not go too deep.”

We were allowed to take pictures [in mainland China] but had to be careful. We could not shoot areas that were forbidden

Ou Ping

As the mainland opened further, they were able to explore more and more places. “We went to many provinces. The mainland has so many beautiful places: you could go to Xinjiang many times and never see everything.”

Getting the perfect image challenged the skill and ingenuity of the PSM team. On one August visit to Yunnan province, they rose at four in the morning in order to capture the sun rising over a mountain range. “We waited three hours, some of the members wanted to leave. If there was thick cloud cover, there would be no picture. We could have been waiting for nothing. But in the end, the cover broke, and the sun’s rays covered a landscape of beautiful colours.”

On another occasion, they travelled to Xinjiang in late autumn. They specifically wanted to shoot images of sheep flocks coming down the mountains. “It was October or November and becoming too cold for the sheep to graze on the mountainside. We positioned ourselves on the downward slope. We did not know exactly when the animals would come, but I was fortunate – the sheep came close to me, their hooves beating the ground and causing clouds of dust.”

Exhibitions in Macao and beyond

Ironically, Ou worked at Macao Daily for over 40 years but rarely as a photographer. “Sometimes, when there was big news, I would help and take photos. This was a matter decided by the company and not by me.” Photography remained a hobby in his spare time.

Over the years, local institutions have held many exhibitions by PSM members, including Ou. They have also shown on the mainland, in Hong Kong, and in 1984, they exhibited in Porto, Portugal.

In 2005, Ou held his first solo exhibition in Macao showcasing a collection of large black and white images. In 2013, the Macao Foundation organised a second solo show at the Military Club, this time a retrospective of his work over a period of 50 years.

Evolving with the times

According to Ou, the city has changed beyond recognition in the past 15 years. “People find it hard to adapt. Human relations are less close than they used to be. We have too many material demands that require money to supply them.”

The medium itself has changed too. Photography has become a mass hobby, with almost ubiquitous use of digital cameras and mobile phones. “I think this is a good thing. The more people take part, the better the artistic atmosphere will be.” Initially, Ou found the move to digital cameras rather difficult, as mastery of the computer was essential. However, he gradually adapted and joined the 21st century. Whether he’s working with film or digital photography, Ou remains dedicated to the same principle he has followed for over 60 years – shooting whatever is around him. His energy and passion have not weakened, and thanks to him and his PSM colleagues, some of the most precious elements of Macao’s history are preserved for future posterity.