TEXT António Bilrero

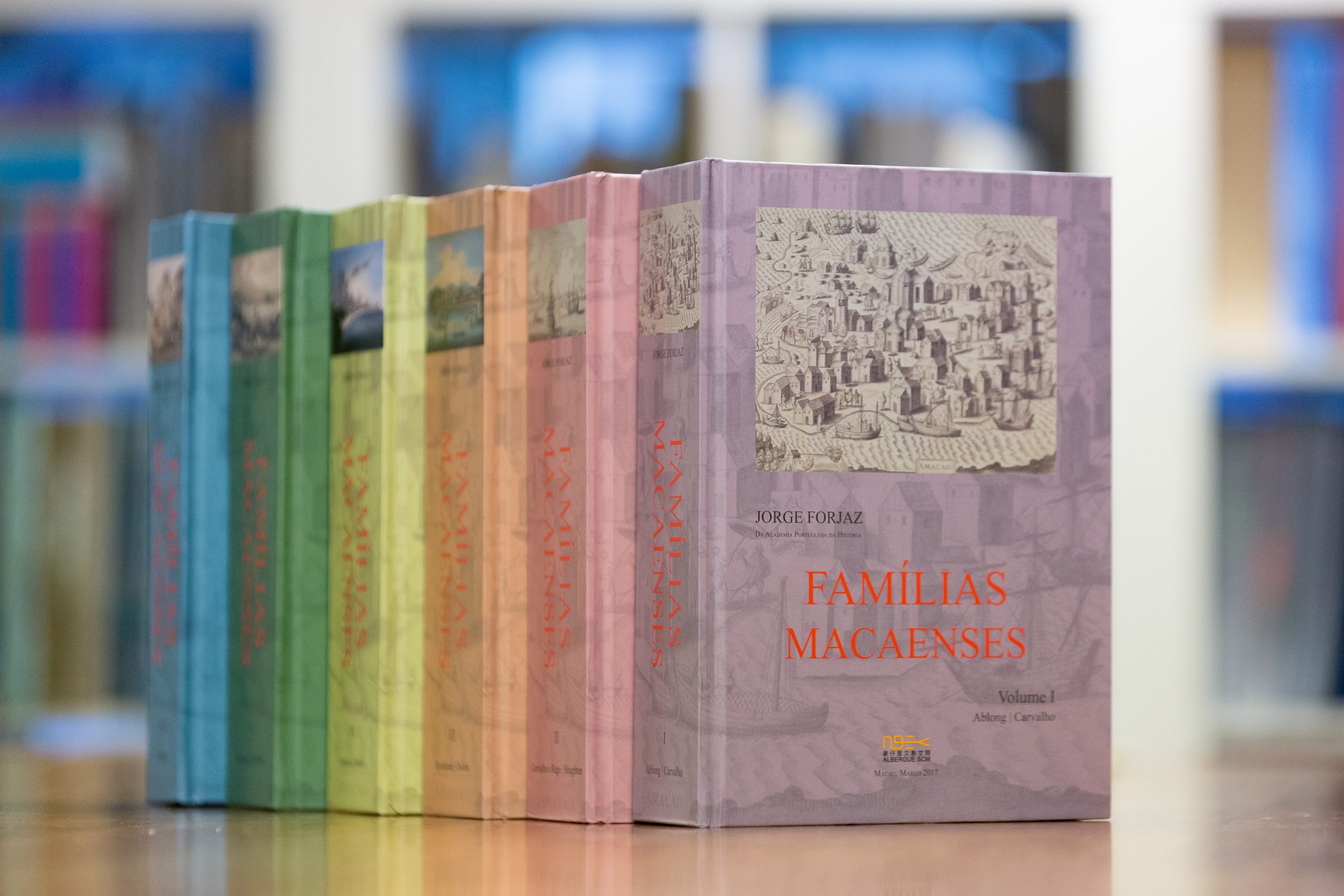

The second edition of Famílias Macaenses (Macanese Families) by the historian and genealogist Jorge Forjaz consists of six volumes with thousands of pages, encompassing nearly 500 families, with more than 70,000 cited names and over 3,000 photos. But this massive collection, the author affirmed, was initially “born by chance.” The first three‑volume edition came out in 1997, followed two decades later in 2017 by the second, revised and updated with 80 new chapters. But Forjaz is sure of one thing: “There won’t be a third edition written by me – 20 years from now I won’t be here to do anything.”

The first question in a long‑distance conversation with this historian and archivist, who lives on Terceira Island in Portugal’s mid‑Atlantic Azores, was to gain an understanding of how a work of that size could come about by chance.

For the author, it’s all very simple. Everything began when he came to Macao in 1989 as resident director of the territory’s International Music Festival. He brought along some papers so he could continue his work on the genealogies of families from Terceira. Genealogy, he said, “is a parallel activity” that has accompanied him since his youth. That’s why he entertained himself during his spare time in Macao by continuing the work of a lifetime: the genealogies of Terceira Island, in around ten volumes.

He recalled that, after three or four months, he “had finished the work with all those papers,” leaving him wondering what he should do with his free time in Macao.

“After a certain time, a historian who’s far from his archive doesn’t have anything new to work on. The archive is the source of his research. So I decided to have a look at what there was about Macanese families. And in the territory there was a historian everyone knew: Father Manuel Teixeira.”

Forjaz had found what he would later call the “key” to his work on Macanese families.

The Catholic priest Manuel Teixeira was, and still is for many, the greatest ever historian of Macao and one of the major researchers on the Portuguese presence in Asia. He left behind more than a hundred historical works, the overwhelming majority of them focused on Macao.

The relationship between the two men began with a conversation at St Joseph’s Seminary, where Father Teixeira lived:

“I wanted to know what he thought about me taking all those things he’d done in a dispersed manner, putting it all together in a new form and eventually developing it in other directions,” Forjaz recalled, referring to the information about Macanese families found throughout Father Teixeira’s work. “And he was fantastic. Above all, beyond opening the door for me to the genealogical world of Macao, Father Teixeira encouraged me: ‘Do it. I would like to have done it, but I’m too old now.’”

That was in 1990, the year the work began.

Forjaz’s commission as festival director lasted from 1989 to 1991. In addition to “reading the entire work of Father Manuel Teixeira,” for those years he spent all his free time reading and investigating in the archives.

“In all the lines, in all the chapters, in all the footnotes of the works by Manuel Teixeira – I found something that interested me and I set it all down. My idea in the beginning was to do something light. I wanted to compile everything that had references to families or individual information about various figures.”

After the bibliographic work had been reviewed, he moved on to research records in Macao. That’s when he had his first “nice surprise” – albeit after a brief shock.

Following the example of Portugal, where parish records had all been transferred to district archives, Forjaz sought that information in Macao’s historical archive only to be informed that it possessed no such documentation.

“I thought my work had ended there. Without parish records there’s no more investigation.”

But someone told him to consult the territory’s parishes, because they might have some of the material he was looking for.

The historian explained that until the 1910 revolution in Portugal all such records – baptism (birth), marriage, and death – were kept in the parishes. Only later, in 1911, were the civil registry services, as they are known today, created.

“And history can only be done with documents. In the world we live in – the western, Christian, Catholic world – we were lucky to have a 16th‑century pope [Paul III] who summoned a council, the famous Council of Trent, and one of its many results was an order for Christendom that all parishes should record who had been baptised, married or died, etc,” he enthused; hardly a surprise, given the primacy of records in his work. “Before the Council of Trent there were no official records, just private ones.”

Regarding Macao, the genealogist recalled the “nice surprise” he found in the territory’s parishes, especially Sé, which boasted a “very well‑organised” archive of records.

“Unlike in mainland Portugal, in the former overseas colonies the civil registry took years to establish; it wasn’t done right away in 1911. Macao’s case is quite exceptional. It only happened around the 1950s. That was a tremendous help for researching the families of Macao,” he noted.

“From then on, I went to work in the churches’ archives. For two years [1990–1991], I spent my weekends, late afternoons, and evenings mainly in the Sé parish archive. It was extraordinary work. I saw all the marriages, all the births, all the deaths from the 18th century up to the date I was working. Everyone passed through my hands; everything fell into the net. In theory, none escaped me.”

He continued: “Meanwhile, the commission had reached an end; it was 1991. I went to speak with IPOR [Instituto Português no Oriente], then headed by Anabela Ritchie, to find out if they were interested in helping support a continuation of the work, as I had already gathered a lot of valuable information. The institute liked the idea and requested the collaboration of Fundação Oriente, which decided to support the project. After [1991], and until the publication of the first edition [in 1997], I visited Macao every year.”

But with so much information available, it would have been a pity to leave out many Macanese families who had settled since the 19th century in Hong Kong and Shanghai, in the latter until the Communist victory in 1949. That’s why, during that years‑long process, Forjaz spent a great deal of time at the then Portuguese consulate in Hong Kong, consulting archives that had arrived five decades previously from the Shanghai consulate. He also visited Catholic parishes in the old British colony.

Later, he added information gathered from many trips to Brazil, the United States, Canada, Australia, and Singapore. “I looked across the whole world after the Macanese.” And there were thousands of letters – “Yes, back then there was no internet” – received in response to thousands of others sent to request information about families so the respective files could be built. A “crazy job” that culminated in the publication of the three‑volume first edition in 1996.

The second edition

Then came the decision to go ahead with a new revised and expanded edition of the work about Macao’s families, a generation after the first. Asked whether there will be a third edition in another 20 years, Jorge Forjaz’s answer is categorical: “Signed by me, there definitely won’t be. Because 20 years from now, I won’t be here to do anything. So in that aspect the case is closed. Even if I am here, it just won’t happen – I’ll be very old.”

But isn’t that what he thought about the second edition?

“Yes. Doing this new edition was also crazy. I’d never thought of doing it. To the point that, when I finished the first one, I turned to other projects,” Forjaz said. Over the years, he compiled genealogies of families in India, Mozambique and São Tomé and Príncipe, travelling from east to west after the former overseas provinces. “For me, Macao was a closed case.”

Forjaz even donated the entire archive organised for the initial edition – namely the correspondence and the library he had put together in Macao – once they were no longer needed at home.

“It was extremely important material and I decided to offer it to an archive in Los Angeles in the United States: the Old China Hands Archives of California State University, Northbridge. That archive has only one aim: to preserve the Western memory in China,” he explained. “They receive donations from families and people who have been all over China. Around 40 crates of material were shipped from the Azores. It’s all there, organised. So the matter of Macao was resolved.”

But – and there’s always a ‘but’ in such stories – he ended up returning to Macao in 2012, 15 years after the first edition, to give a lecture about Macao families at the invitation of his friend, the architect Carlos Marreiros, and the Albergue.

“At that conference, Carlos Marreiros put forward the challenge: ‘How about a second edition?’ It’s usual to think of one when the first is sold out. To issue a new edition, exactly the same as the first one,” Forjaz reflected. It didn’t seem possible at the time, though, since he lacked sufficient information to build on his existing work.

But then, he acknowledged, he began “pondering the matter.”

“And I recalled that the times were different, we’re no longer in a time of letters, it’s the time of the internet. Telephones nowadays have become very easy to use. Meanwhile, I consulted the Archives of Macao and there were new arrangements enabling documentation to be reviewed,” he explained. Confident that the resource landscape had changed since his first edition, completed in the early days of the internet, Forjaz had a change of heart: “I thought that maybe there were conditions to do a new edition, with new and updated information.”

He also benefitted from a phenomena common after the publication of genealogies: people offering him information, instead of the other way around.

“[Genealogists] write, make phone calls, knock on doors to ask for information. Genealogy has two times: historical time and current time. Historical time is when, during that research, you learn in the archives and records who the parents, grandparents and great‑grandparents are, etc. But later, if you want to find out who the children or grandchildren are, you have to ask, telephone, send an email to obtain information,” he explained. For all the work involved, results can be difficult to come by.

I recalled that the times were different, we’re no longer in a time of letters, it’s the time of the internet. Telephones nowadays have become very easy to use.

Jorge Forjaz

“Hundreds either don’t answer or provide only a rough reply. Sometimes it’s easier to find out the name of a great‑great‑grandfather than to learn the name of a grandchild. And a genealogy can’t be made with the just the name José or João. You have to enter information such as full name, place of birth, name of parents, studied here, degree from there, etc… The file has to be complete or as complete as possible. A genealogy is not a telephone directory of names.”

After the first published edition, he had received “an unimaginable number of letters saying… ‘I’d like to complete my chapter – this, that and the other thing are missing.’ But once published, nothing can be done.” He held onto the letters nonetheless, and when embarking on the second edition, he used them to update the information.

Technological progress also made its contribution. “For the first edition I wrote individual letters, addressed to each person. This time I sent, for example, one email to Casa de Macau in Australia asking it to ‘please inform your members that I’m working on this’… In most cases after a week went by I started receiving information.”

Taken together, these resources allowed Forjaz to collect a massive amount of information on which to base a new edition. “It was a big leap. For now, what happened in the last 20 years has been updated, corresponding to a generation. Later, the genealogies which were incomplete in the first edition of the work were finished, and that allowed me to add nearly 80 new chapters about the families missing in the first edition,” he underscored.

For Jorge Forjaz, one particular type of addition proved the “cherry on top of the cake”: photographs.

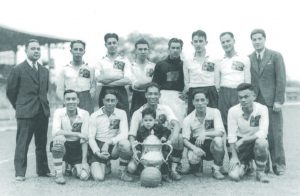

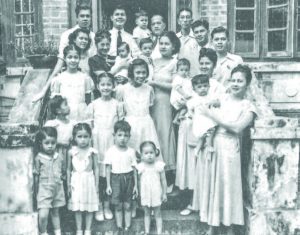

“In the first one there are 150 or 200 photos. In the second, there are more than 3,500, and the photos are the portrait of peoples’ souls. They have a name and a date. When you have a photo, you can see the person. There are fantastic photos from Shanghai and Hong Kong. Interestingly, I have older photos from that area of the world than from families in the Azores. So that’s how the second edition was born.”

Despite his repeated, and sincere, assertion that he won’t be doing a third edition, there may still be more to come: “I believe what will happen in the future is that the information will be updated on the internet, without a new printing.

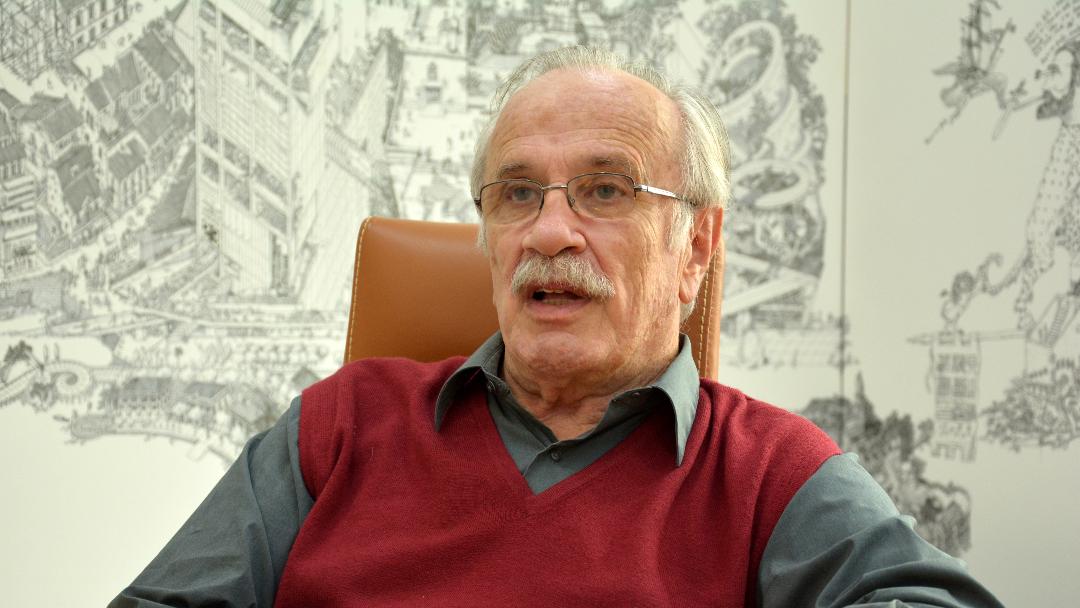

About Jorge Forjaz

The historian and archivist Jorge Forjaz was born in November 1944 in Angra do Heroísmo in the mid‑Atlantic Azores. He has a history degree and a passion for genealogy, is married with three children and grandchildren. He once worked in the Public Library and Archive of Angra do Heroísmo. He then served as regional director of cultural affairs of the Azores Autonomous Region, secretary‑general (resident director) of the Macao International Music Festival and cultural attaché of the Portuguese embassy in Morocco. He worked as director of the Museum of Angra do Heroísmo and also produced five television series for RTP‑Azores, notably “In Webs of Silk.” He has been a corresponding member of the Portuguese Academy of History since 1997. Jorge Forjaz’s more than 30 published works mainly focus on genealogy of the Azores, particularly Angra do Heroísmo, though others also stand out: Macanese Families, awarded by the Fundação Oriente – Portuguese Presence in the World Prize of the Portuguese Academy of History; Luso‑Descendants in Portuguese India, Portuguese Families of Ceuta and Genealogies of São Tomé and Príncipe – Benefits, Honorifics of the 20th century (1900‑1910).