Muay Thai has a long and rich history in Thailand. In Macao, the sport hasn’t acquired quite the same legacy, to say the least. While it would be hard to compete with the birthplace of Thai boxing in any case, professional-focused Muay Thai gyms only started to appear in the city in the 1990s, and even then, they only attracted about a dozen serious athletes. But now, the Macau Muaythai Association (MMTA) hopes to build the sport from being just a niche activity. First, however, they must change peoples’ minds – not to mention their mission.

In the early 1930s, Muay Thai was systemised with a set of rules. Since the 21st century, it has gained more attention after it was officially recognised as a sport by several international bodies, including the International Olympic Committee (IOC) (it is officially known as one word, muaythai, as the IOC does not allow official sports to have a country name in it). But Muay Thai is arguably more popular as a casual practice for many people, either as a way to keep fit or as a form of self-defence. Today, many Muay Thai organisations aim to leverage this growing popularity to get more people engaged with the sport and its traditions on an official level. That includes the Macau Muaythai Association.

Established in 1997 by Muay Thai enthusiast and advocate Vong Veng Im, in cooperation with the Sports Bureau of Macao and the International Federation of Muaythai Associations (IFMA), the MMTA is the city’s spiritual centre for the sport. But today the MMTA is stepping in a new direction. As part of the changes it’s undergoing, the association aims to bring in more female athletes, educate children about Muay Thai, and find new talent to train fighters and represent Macao in the future. It’s a sizable challenge, but one the MMTA, as well as Macao’s up-and-coming Thai boxing talent, are ready to face.

Developing champions at home

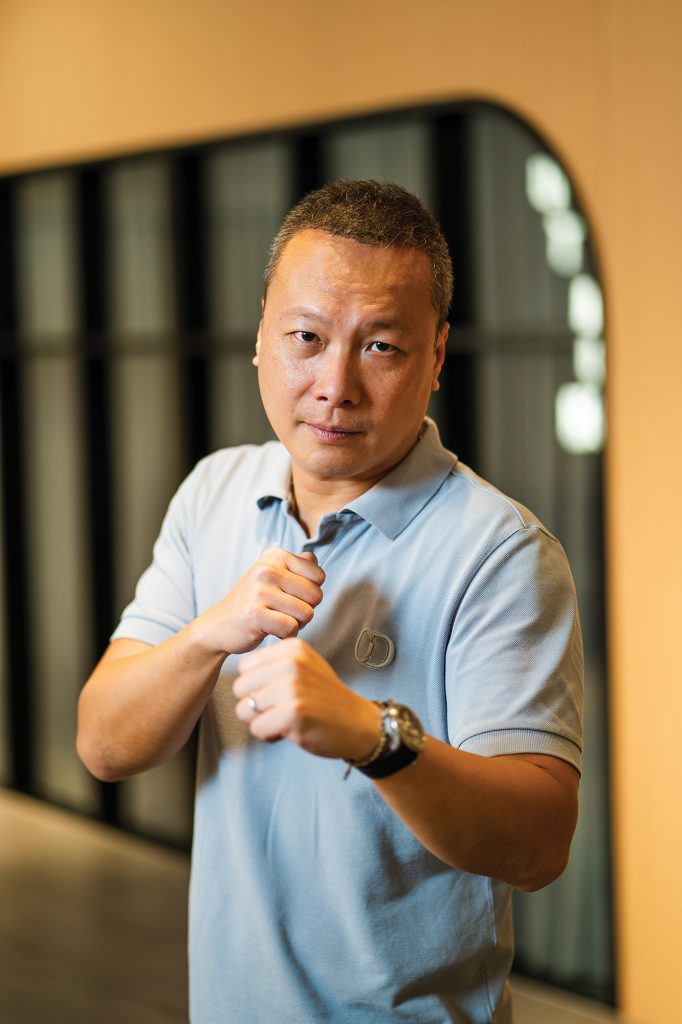

When the MMTA began, its mission was rather noble. At the time, the association had around a dozen athletes, all of them men, and all focused on winning titles. “It was all about going for the belt and heroism back in the day,” says Iao Chi Lam, the newly appointed chairman of the MMTA. “From the 2000s until the early 2010s, it became more commercially driven, where fights had sponsorships and athletes wanted to do it only for the money.”

Today, the MMTA has approximately the same number of fighters, and still more men than women. But Iao has been tasked with shifting the association’s focus to get more people interested in Muay Thai, men and women alike, and at a younger age. He might start by drawing on his own experience with the sport.

Born in Macao, Iao has been practising Muay Thai since he was 13. He insists that the sport is more than meets the eye. Rather than simply teaching athletes how to fight, he believes it can help with self-defence and weight loss. “I started practising Muay Thai because Macao, back in the ’80s, was a lot different than it is nowadays,” Iao says, hinting at Macao’s rough and tumble nature at the time. “But also, from a young age, I’ve kept my cardio going, and as I grow older, I’ve realised how important that lifestyle is.”

But Iao is aware of the challenges ahead as he tries to rebuild the MMTA for the modern age. The number of athletes has dipped and climbed over the years, and Muay Thai is not as popular in Macao as other sports, such as boxing. “It’s like running a business; you need to go along with the economy and what the market demands,” he says.

Currently, the market demands a move from its current location, as well as cultivating new target groups. The MMTA will be moving its facilities on Avenida do Almirante Lacerda to Life Project Macau, a local gym in Emperor Nam Van Centre Avenida do Infante located in Macao. “The Sports Bureau has also been supportive with the restructure,” Iao says. “They said that children should be educated at a younger age so they understand the principle of the sport before they can pursue it as recreation or a profession.”

Even before the MMTA’s official shift to focus on youth development, Macao was making waves in Muay Thai internationally. In 2018, Macao hosted the Asian Muaythai Championship. Having the event on home soil gave Macao athletes an opportunity to compare themselves against other top competitors, and it gave organisers and coaches a chance to see how other countries operate. For Iao, it was an eye-opening moment.

Iao says he was astonished by the support some teams received. “The head of sports of Kazakhstan sat beside me, and I found that amazing since it was not just the coach and athletes of the country coming to Macao to support them,” Iao says.

At the event, Macao athletes made a mark, too. Tam Si Long, 29, a student at the Macao Polytechnic University, claimed first place in her division (the senior female continental championship – Elite A – 48kg). Tam won cash prizes from the MMTA as well as the Macao government for her win, and she created a positive impact not just for herself, but for all women in the city as well. “It made people realise that [women] can also learn Muay Thai and participate in competitions,” Tam says.

For the MMTA, Tam embodies exactly the kind of athlete the association hopes to develop. Martial arts became part of her life when she was just 6 years old. When she was young, she participated in many judo (a Japanese unarmed martial art) competitions, saying

that the “taste of winning was enticing”. At 19, she joined Fighting Arts Club Macau, a sub-association of the MMTA, and was trained under her sifu (master), Sio Chi Hong.

“He was my mentor,” Tam says. “His philosophy was to never give up easily. From him, I’ve learned [how to develop] wisdom from hardship and let failure strengthen my will.”

Previously Tam had competed at the IFMA World Championships in 2012 and 2014 in Thailand and Malaysia, respectively – her first two official competitions. Having only started her journey in Muay Thai when she was 20, she claims that she lacked experience and technique. By the time the 2018 Asian Muaythai Championship came around, she says she was starting to peak.

The year prior, she participated in the 2017 World Games held in Wrocław, Poland, where she fought against competitors from around the world and came home with a third-place finish. She explains that it was one of the key factors to her success in the 2018 Asian MT Championships. “I defeated some tough opponents from countries like Russia and Poland,” she says.

Throughout her athletic career so far, Tam has faced victory as well as defeat, but the thought of giving up never occurred to her. “The outcome of your effort is not always as satisfying as you expect. I didn’t win all my competitions, but I do my best, with no regrets. That’s my mentality,” she says.

On top of competing professionally, Tam coaches at the Fighting Arts Club Macau. She has worked at the club for seven years, leading group classes as well as one-on-one sessions. From the many athletes she has worked with, though, Tam says that only two or three are qualified to participate in competitions. Most treat Muay Thai as a hobby. “It’s too difficult to [train at an elite level] in Macao,” Tam says. “Taking myself as an example, I’m an amateur boxer that needs to work [to make a living]. It’s not like other places that allow you to be a full-time athlete.”

Tam might have an opportunity to change that soon, though. She is set to join the board at the MMTA. While changing the way athletes receive sponsorships isn’t at the top of her agenda yet, she has already set a key goal for herself, one that could shape the sport for years to come. “I want to change people’s minds. To me, men and women are equal,” Tam affirms. “I won the Asian MT Championship, and through that, I want to show other women that they can do it, too.”

Next-gen coach

The MMTA plays a major role in developing Muay Thai in Macao, but it isn’t the only game in town. Young coaches across the city are working their way up independently. One of them is Macao-born Nicole Placé, 24, who says she got into martial arts 11 years ago after watching Angela Lee, the Canadian-American mixed martial artist (MMA) and youngest ever MMA champion, fight on television. When Placé turned 14, she began training at Warrior Fitness, a gym on Avenida Olimpica in Taipa, with coaches from the Philippines martial arts team Lakay, including Mark Eddiva, a former MMA athlete and wushu (also known as kungfu, the famous Chinese martial arts) champion.

“Personally, I think Muay Thai is more interesting than other martial arts,” she says. “You have a variety of moves and all of them just look really cool. I wanted to learn that and the more I trained, the more I fell in love with the combat side of things.”

To date, however, Placé has struggled to compete as there are few other athletes in her weight class. Her coach, John Paul Fernandez, tried to set her up with a couple of official fights, but it would have required cutting down on weight. “I knew that if I did cut down to the weight that I’d be competing in, then I would not be performing at my best,” she says.

Despite her lack of fighting experience, she is deeply involved with the sport. At the onset of the pandemic, Placé decided to get into coaching. She got her international certified licence from the National Academy of Sports Medicine, where she learned about the human body, exercises and science. In the middle of 2021, she joined Flex Fitness, a commercial gym, before moving to Warrior Fitness in November 2021.

“It takes some time to get used to coaching,” Placé says. “I used to watch how my coaches coached me and it kind of got drilled into me, like, ‘Okay, these are some of the options of coaching style or structure’.”

Like Tam, Placé also hopes to encourage more women to try the sport. She leads three classes per week and coaches privately outside Warrior Fitness, mostly with working professionals who have nine-to-five jobs. Some want to shake up their workout routine with Muay Thai, a sport they find more dynamic than boxing. Some come to her with some experience and like the way she coaches. And others come to her as total rookies with a deep interest in Muay Thai but no experience whatsoever. Whatever their reason for working with her, Placé says her “biggest goal is to just ignite people’s passion”. She also hopes to shatter stereotypes about the sport. “[Some people say] that Muay Thai fights [look] very messy. I think it’s a very elegant sport when you put in the time to train and you [find] your techniques. It’s almost like a dance, in a way.”

Although she enjoys training others, she still hopes to compete, too – first locally, and then internationally. Prior to the pandemic, she had hoped to attend a fight camp in Thailand alongside some of her pro-fighter friends.

“Thailand is the motherland of Muay Thai and I’ve seen results from friends who have attended the training camps there,” Placé says. “I believe that it would also help me be a better coach and fighter.”

Though not many athletes practise Muay Thai in the city today, the MMTA and independent coaches alike seem to have the right mindset to push the sport to the next level soon. “The younger generation will be our future fighters, so we want to put the focus on them as well as female athletes,” Iao says. “We already started by putting ourselves in a position to prepare for [growth], so that’s why I keep on saying, ‘We focus on educating the younger kids; doesn’t matter what gender’, [so that we can] have that massive pool of athletes to select from.”

Mesmerising techniques

Muay Thai, also known as the “art of eight limbs”, dates back to the 13th century in Thailand, when it was developed as a form of combat for foot soldiers. Today, fighters draw on the sport’s battlefield legacy, using their fists, elbows, knees and shins – the eight limbs – in different combinations to wear down opponents. Every fighter develops their own style as they grow up, but there are five core forms athletes learn:

– Muay mat (‘puncher’): An aggressive style that relies on punches to wear down opponents.

– Muay femur (‘technician’): Known as one of the most skilled techniques, this style prioritises strategic hits over powerful blows.

– Muay tae (‘kicker’): A style that centres on a variety of kicks with strikes to the head, neck, ribs or thighs, all with great force.

– Muay khao (‘knee fighter’): Fighters use the knee for attacks, often resulting in hard strikes to the opponent’s torso.

– Muay sok (‘elbow fighter’): Fighters rely on the elbow to send a variety of blows to the upper body.

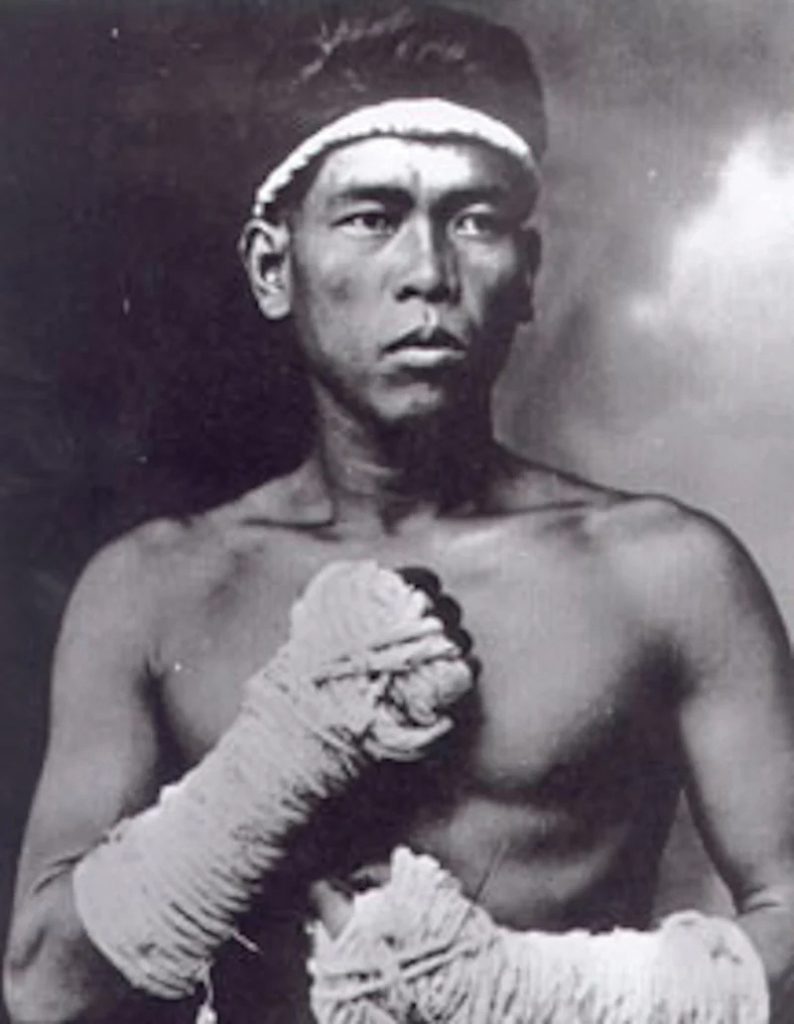

The Father of Muay Thai

A familiar name among Muay Thai athletes is Nai Khanom Tom, also known as “The Father of Muay Thai”. In 1765–1767, the Burmese raided Siam, known as Thailand today, in Ayutthaya, the former capital located 80 km north of Bangkok. King Mangra of Burma held a victory celebration and invited some of the finest Burmese fighters to fight against the slaves brought back from Thailand. Among them was Nai Khanom Tom.

Tom asked for a minute to prepare, and in that time he performed a ritualistic dance, today called the Wai Kru Ram Muay (a dance to pay respects to their trainer, loved ones and country). Nai Khanom Tom rained down on his opponents with a fury of elbow strikes and kicks, catching the king’s attention. Tom was offered freedom and returned to Thailand as a hero, where he spent his entire life teaching Muay Thai. In honour of his name, 17 March is celebrated in Thailand as National Muay Thai day.