Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District is no stranger to eye-catching architecture. The ambitious development, situated across the water from the Macao Ferry Pier along Victoria Harbour, is the city’s largest arts centre, and it has the infrastructure to prove it, from the M+ museum’s billboard-like façade to the Xiqu Centre’s imposing industrial design.

The latest addition to this already impressive skyline is the Hong Kong Palace Museum, which just opened its doors last month. The HK$3.5 billion (MOP 3.6 billion) project takes its name from the Forbidden City Palace Museum in Beijing, where most of the art pieces are on loan from.

The building’s outer walls are made from golden curved aluminium panels, referencing its sibling from the imperial age. Inside, three atriums stacked atop one another connect the museum vertically, a contemporary reinterpretation of the linked courtyards in the Forbidden City.

This intricate attention to detail speaks to the museum’s goal of showcasing 5,000 years of Chinese civilisation by acting as a treasure chest of ancient artefacts.

Ambitious beginnings

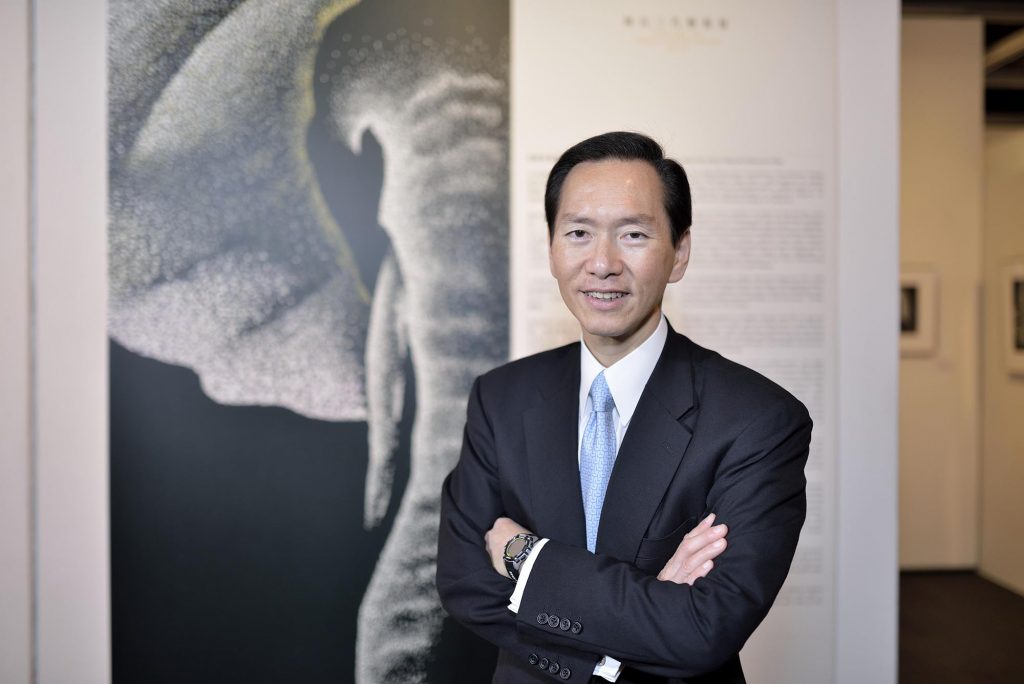

The Hong Kong Palace Museum came together in record time. Bernard Chan, chairman of the museum’s board of directors, says that the idea came to former Chief Executive Carrie Lam about seven years ago. Prior to this, different museums across Hong Kong had regularly hosted exhibitions featuring pieces from the Palace Museum and were usually sold out. During a visit to Beijing in 2015, Lam thought Hong Kong would benefit from having its own dedicated space for national treasures.

“It was her idea, together with the endorsement from the Beijing Palace Museum director that got this whole thing started,” says Chan.

By October 2016, Lam had secured funding from the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust to build the project, and an announcement was made to the public in December with a goal to have the museum completed by July 2022, in time for the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover. Local firm Rocco Design Architects was directly appointed to design the building.

The project was initially met with some criticism by Hong Kong residents who pointed out that the public was not consulted about the museum – the standard practice for the construction of public facilities. Some also criticised the decision to directly assign an architecture company instead of having an open tender.

In defence, Chan argued that putting together the Hong Kong Palace Museum required working closely with the museum in Beijing to secure a contract for the loan of its exclusive artwork; Hong Kong officials could not afford to risk having the project being rejected by the public.

“I was told many cities want to get their own Palace Museum. Shanghai could do one also … this kind of thing is very competitive, so you don’t want to throw it [the responsibility] to the public. What if you do a public discussion and at the end you don’t get their support? You’ll [turn] this thing into a huge embarrassment. So I think that’s why it couldn’t be done from the bottom up. It had to be done on a high level to secure the deal,” Chan said.

He added that avoiding the usual bureaucratic processes allowed them to complete the project on time and HK$240 million (MOP 247 million) under budget.

Curating challenges

Building a museum of this scale on a tight deadline was challenging enough, but doing so during a time of political turmoil (2019 protests in Hong Kong) and a global health crisis added other hurdles.

In 2019, Daisy Yiyou Wang was brought onto the team as deputy director of curatorial and programming. Born and raised in Hunan province, Wang was previously based in the United States, where she worked as a curator of Chinese and East Asian art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts and the Chinese art specialist at the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, DC.

“In the United States, the museum business has [existed] for over 100 years, so it’s a very mature system. Doing an exhibition there is like regular warfare – you know what you’re getting into, you know what weapons you’ll use and you’ll know how long it will take. But in Hong Kong, it’s more like guerilla warfare. You have to be very nimble and you have to be prepared for unexpected situations,” Wang admits with a laugh.

One of her biggest challenges was procuring display cases for the most valuable pieces. The Palace Museum in Beijing had agreed to loan 166 first-grade cultural relics, a rating that means they are recognised as national treasures. “These are treasures [among] treasures,” Wang explains. “The Forbidden City Palace Museum has over 1.8 million objects, but only about 8,000 are considered first-grade treasures, and out of those, they gave us 5 per cent [of them].”

It was Wang’s responsibility to make sure they were appropriately stored and displayed upon their arrival in Hong Kong. She enlisted the help of Italian display manufacturer Goppion, who created the display case for the Mona Lisa in the Louvre. The cases had to be tailor-made, but because they didn’t have the exact dimensions of the objects at the time, Wang had to make sure the display cases were modular to make them as versatile as possible. At one point, they were worried they wouldn’t make it to Hong Kong in time because production was halted in Italy during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic. In the end, they managed to receive the display cases in time for the artefacts’ arrival.

Transporting nearly a thousand artefacts from Beijing to Hong Kong also presented a huge logistical undertaking that had to be carefully orchestrated. “It dawned on me that you can’t just ship them all in one go.

There are very specialised packing, unpacking and shipping services that are accustomed to moving treasures like this,” says Chan.

Chan also said that just insuring the items during their transit cost “a couple million US dollars”. Plus, the artefacts are so valuable that insuring them during their stay in Hong Kong involved more than 100 different insurance companies from around the world – a record feat that will cost the museum another few million US dollars per year, according to Chan.

From the Forbidden City to Asia’s World City

The efforts paid off when the Hong Kong Palace Museum opened on time on 3 July, ahead of the city’s handover anniversary. Eighty-five per cent of the 140,000 available tickets were sold before the opening, and Wang says most tickets for weekends in August are already sold out.

With nine exhibition galleries spread out across 7,800 square metres of space, the Hong Kong Palace Museum boasts 914 pieces on loan from the Forbidden City, ranging from painting and calligraphy to bronze, ceramics, jade, costumes, jewellery and architecture, dating back nearly 5,000 years.

“Some of these [items in the museum], many of us probably studied or saw in a textbook but this is the first time we can actually see it in person,” Chan notes. He says being able to view the relics in person will generate newfound appreciation amongst visitors.

The first two galleries serve as an introduction to the Forbidden City, showing visitors how life in the imperial palace influenced Chinese politics and culture. Chan explains that he understands that younger people may not necessarily have a natural interest in ancient items, so it was crucial for him to make the museum cater to these audiences with interactive elements.

“What impressed me the most was gallery five. That’s not where all the great [pieces of art are], but what I like about it is we use a lot of advanced technology to create an immersive experience, mixing the old and new together,” he says. “I think the Palace Museum normally gives the impression of having a more mature audience. I want to change that stereotype.”

Wang agrees, saying that when working with the museum’s 12 curators, it was crucial for them to create something for everyone. “I think offering multiple entry points is very important for our museum. We have scholarly exhibitions, but most are [also] immersive and very interactive. There are a lot of multimedia elements. For example, there are stations where you can do calligraphy … we have a lot of things for multi-generational families.”

A global outlook

The Hong Kong Palace Museum also wants to make a name for itself beyond its counterpart in Beijing. Bernard Chan says that they are not merely a branch of the Forbidden City Palace Museum but an institution in their own right contributing a unique perspective to the art world.

“We want to take advantage of the mix of East and West in Hong Kong. We’re here to showcase Chinese civilisation to the world. The world is so polarised today; we want people to experience and understand through the exhibitions how [historically] our civilisation co-existed with other civilisations,” Chan says.

To do this, the Hong Kong Palace Museum also features works from around the world. Currently, there are 13 pieces of art on loan from the Louvre in France. Wang says they are working on a future exhibition featuring treasures from Liechtenstein.

She encourages everyone to visit the museum as soon as they get the chance, as some pieces will only be in Hong Kong for a few months. Some of the pieces, mostly those on loan from Beijing, will probably have to go through a resting period of at least a few years – meaning, the museum would put them in storage out of conservation concerns – before they can be displayed again, too. “To me, this is a gift to the world as much as it is a gift to the people of Hong Kong.”

Chan hopes that putting ancient works of art from different civilisations side by side will instil a potent lesson to visitors. “There are Chinese artefacts with strong Western influences and there are Chinese influences in some Western art as well. These things go back thousands of years. I think that’s a powerful message.”

Must-see treasures at the Hong Kong Palace Museum

Ding kilns, Hebei province, Northern Song dynasty, 960–1127

Stoneware with ivory glaze

This headrest was produced by the Ding kilns, one of the “Five Famous Kilns” of the Song dynasty and is a rare example of its kind. The Qianlong Emperor collected several Ding ware headrests, for which he composed many poems. One of these poems reads: “On all fours, he has a focused gaze. What a pity that the child now serves as a headrest and cannot go to sleep!”

Twelve chrysanthemum-shaped dishes

Imperial Kilns, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province

Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period, 1723–1735

Porcelain with overglaze enamels

Inspired by the shape of chrysanthemums, each of these dishes is covered with a striking, coloured glaze. Some of the colours were invented during the Yongzheng period. The dishes were part of 40 sets commissioned by the Yongzheng Emperor from the Imperial Kilns in Jingdezhen in 1733. Most of the rest of the sets have been lost.

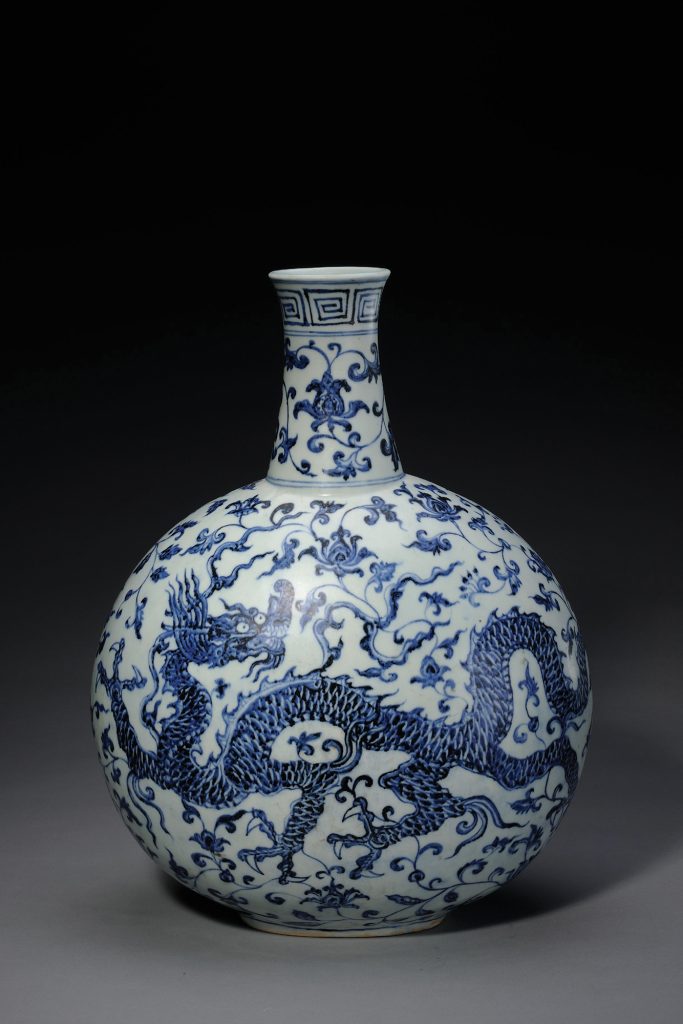

Imperial Kilns, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province

Ming dynasty, Yongle period, 1403–1424

Porcelain with underglaze cobalt blue

The form of the flasks was inspired by vessels from the Middle East. Samarra Blue, a cobalt pigment imported from this area, was used to decorate the body, producing a rich and brilliant colour. The dragon is rendered in a lively manner and intertwined with meandering floral scrolls. The flask reflects the interaction between the Ming dynasty and the Islamic world.

The Qianlong Emperor in Armour on Horseback (available for viewing soon)

Qing dynasty, Qianlong period, 1758

Hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk

Painted by the Italian Jesuit and Qing court painter Giuseppe Castiglione (also known by his Chinese name Lang Shining). Castligione was trained predominantly in Western-painting styles but also learned traditional Chinese painting techniques during his time in China. This mix of methods is evident in this particular piece.

Ten Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

Southern Song dynasty, 12th century Handscroll, ink on paper

This handscroll is the only surviving work bearing the signature of Zhao Fu. Zhao Fu was a native of Jingkou (present-day Zhenjiang province) who lived on Mount Beigu near the Yangtze River. He excelled at painting landscapes, rocks, rivers, and waves. Compared to other painters who often depicted water with lines (if at all), Zhao Fu was unique in that he used layers of subtle wet washes to evoke the ever-changing scenery of the river, creating a sense of spatial depth that animates the pictorial space.