TEXT Joaquim Magalhães de Castro

PHOTOS Eric Tam and Mércia Gonçalves

The Jesuit’s profound knowledge of Japan, where he spent 33 years of his life, earned him the nickname Tçuzu, or the Interpreter

Of the more than 200 Jesuits buried in the church of St Paul in Macao, there is one in particular who stands out: João Rodrigues. His profound knowledge of Japan – a country where he spent 33 years of his life – of its people, language, and culture earned the Portuguese man the nickname Tçuzu (Japanese tsūji), or the Interpreter.

Born around 1561 in Sernancelhe, diocese of Lamego, in the north of Portugal, Rodrigues went on to author the first grammar of Japanese language and many other works covering areas ranging from history to geography to astronomy to simple chronicles of customs.

As well as an attentive observer, diplomat, and researcher, Rodrigues was also a skilled businessman and restless adventurer always driven by an altruistic and curious spirit. His time in Macao and subsequent visits to China are testimony to that.

Forced to leave Japan in the wake of the Madre de Deus incident, Rodrigues arrived in Macao in 1610, at the age of 49. Macao was then a flourishing warehouse, vital to the commercial activities of the Portuguese. It was not his first visit: he passed through the city in April 1577, en route from Goa to the mission in Japan. Nearly 20 years later, in 1596, Rodrigues returned to Macao where he was ordained a priest.

The first days of his stay in Macao were marked by a period of great diplomatic tension between China and the archipelago of Japan, motivated by piracy, which led to a rupture in official commercial relations between the two territories. The situation would prove to be of great benefit to the Portuguese merchants who soon turned the port city into a revolving platform for economic activities between China, Portugal, and Japan itself.

Although no details are known of the first two years of his stay, it is known that Rodrigues was put in charge of drawing up the annual report for Rome, and shortly thereafter accompanied the delegation of Portuguese merchants to the Canton Winter Fair as chaplain. Held twice a year over a period of several months, the fair was the only occasion when the Chinese, distrustful by nature, officially authorised the Portuguese to enter the Middle Kingdom. Whenever this opportunity arose Rodrigues took advantage of it, involving himself in the most diverse and controversial subjects.

He remained in China (mainly in Zhejiang province) between 1612 and 1615, playing a key role in revising the Chinese calendar at the emperor’s request and engaging in heated controversy with fellow Jesuits about the religious terminology to be used in mission work in China. The renowned interpreter argued that Latin and Portuguese terms should be used to express Christian concepts, as happened in the evangelisation of Japan.

Rodrigues also maintained good relations with the highest dignitaries of the reigning Ming dynasty. His stay allowed him to deepen his knowledge of Chinese culture, especially his religious practices. To this end, he wrote: “During the years I was there I was in charge of ascertaining the root of all these sects I had studied in Japan. For this, I ran China and all our residences and other parts where our people had never ventured.”

Upon his return to Macao in 1615, Rodrigues found a much larger Jesuit community, the result of the arrival of missionaries expelled from Japan in 1614. Rodrigues worked tirelessly in his efforts to resolve the enormous problems faced by his former companions, now exiled like him. However, in the little free time he had, he never neglected his contact with the Chinese authorities in Guangzhou, which earned him respect and admiration.

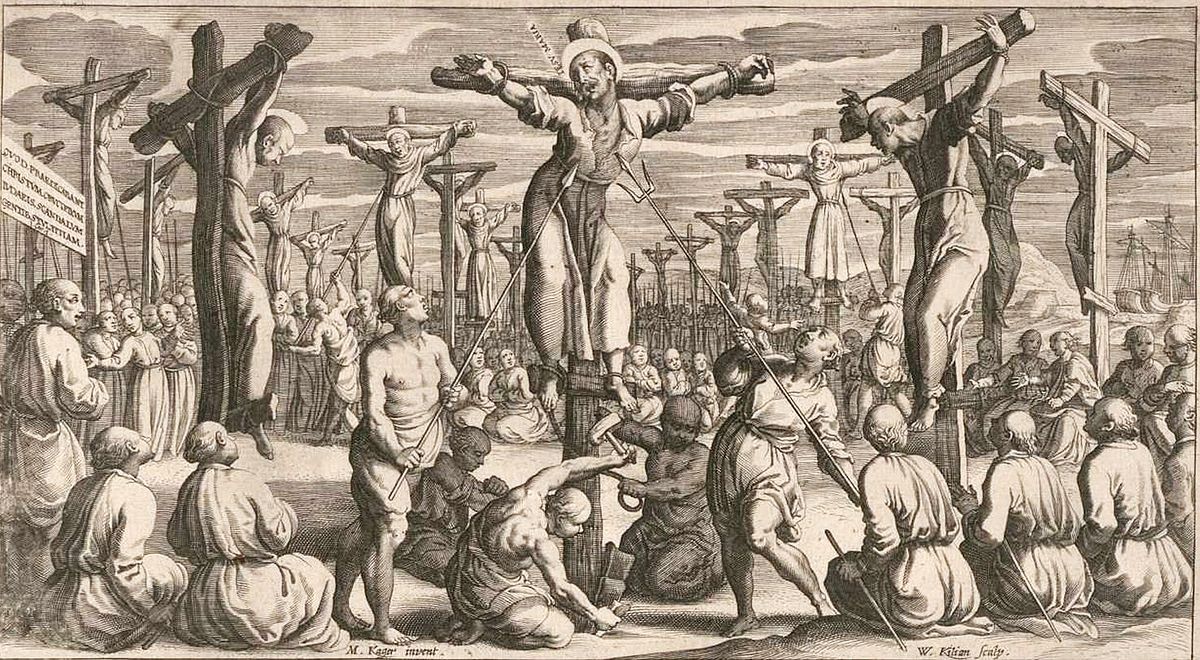

During his time in the territory, Father Rodrigues taught at St Paul’s College, teaching sermons, performing parish functions and working as an attorney. Of note is his role as mediator in religious conflicts and his negotiating genius in Guangzhou on the delicate issues of the construction of defensive walls (an urgent situation after the attempted invasion by the Dutch in 1622) and the property rights of the Jesuits on the grounds of the Ilha Verde, where, incidentally, Rodrigues lived and wrote many of the pages of his story. He openly criticised the “petty and prejudiced spirit” of the new generation of missionaries, interceding to save the Spanish priest Adriano de las Cortes from an almost certain execution. He is the man behind the revelation to the Christian world of the discovery of the Nestorian stone in China, proving that the “law of God our Lord entered China about the year 636AD.”

The desire of the aged and sickly Rodrigues to return to Japan, “since that’s where I went when I was a youngster,” expressed in a 1622 letter, was reiterated five years later.

Yet he never returned to Japan. Instead, an extraordinary final adventure awaited him: in the space of little more than three years, Rodrigues visited Beijing on three occasions, accompanying several Portuguese artillerymen called from Macao at the urgent request of the emperor, as the Manchus threatened to take over the capital. The Portuguese aid would prove providential.

Thanks to the Carta Annua of 28 November 1620, written in Macao by the Jesuit Wenceslas Pantaleon Kirwitzer, we know that during the invasion of China by the Manchus, Paulo Xu Guangqi proposed that the Portuguese of Macao help the Ming dynasty. Xu, a state official and scholar converted by Father Matteo Ricci, immediately tried to send Christians Michael Zhang Tao and Paulo Sung to Macao, on his own initiative. In October 1621, they were received by the Portuguese authorities who, since they were not official emissaries, would only entrust the two men with four cannons and some artillerymen. On reaching Guangzhou, however, the latter were sent back to Macao, with the local mandarinate seizing the cannons.

Beijing made a new request in 1623, this time official in nature. Satisfied with the recognition by the imperial court, Macao sent Captain Lourenço Velho and 23 Portuguese men, including Father Rodrigues in the role of interpreter. To the four cannons thirty other pieces were added, all salvaged from a wrecked Dutch ship.

This military aid forced the Manchus to retreat, but not without a price: artilleryman João Correa and four Chinese men lost their lives to a weapon that violently backfired. In spite of this incident, the provision of the Portuguese made an excellent impression on the imperial court, with its prestige considerably increased. Indispensable in the war against the Manchus, the Portuguese gunmen would be requisitioned again in 1628, following a new attack on Beijing. The request was made directly by the Chongzhen Emperor to the Jesuits, who commissioned Father João Rodrigues Tçuzu to present him to the Senate of Macao, the City of the Holy Name of God.

A battalion with more than 200 soldiers, most of them Portuguese born in Macao, left for the capital of the empire on 16 August 1630. The men marched under the orders of captains Pedro Cordeiro and António Rodrigues do Campo, accompanied by Rodrigues, who, in addition to being the interpreter, was also a political adviser. The presence of priests in the military was justified by the fact that they had mastered the strategies of shooting and tactics, and also by speaking the language of northern China, they were the only ones capable of giving instructions to the local soldiers.

The sight of this entourage in the cities of the empire caused great amazement. Nevertheless, upon arriving in Nanchang, an instruction issued in Beijing ordered their return to Macao. Only Father Rodrigues, Captain Gonçalo Teixeira Corrêa, and some of his men – who would later play a decisive role in defending the city of Chochow – were allowed to continue their journey. Further north, in Dengzhou, Shandong province, this contingent joined the Chinese forces of the city then led by a Christian named Inácio Sun Yuanhua, and there they provided military training and assistance.

But in 1632, the city garrison, consisting chiefly of Manchu mercenaries with payment in arrears, revolted and pillaged the city. Teixeira and most of his men lost their lives in the fray, only Father Rodrigues and three soldiers who had taken refuge in Beijing, escaped. This episode would be recounted by Rodrigues in 1632 in his Memorial das façanhas do valente capitão Gonçalves Teixeira.

The Portuguese experienced brief moments of glory, and innumerable precarious moments provoked by the intrigue of the mandarins of Guangzhou, always very ambiguous and whose power frequently exceeded that of the emperor himself. On the one hand, they defended Macao and the Portuguese, with whom the mandarins were doing business. On the other hand, the mandarins feared that the prestige gained by them, because of their knowledge and military technology, they were able to negotiate directly with all of China without recourse to intermediaries. That is why it was necessary to limit or even put a stop to the initiatives of the “barbarians of the South.”

It was precisely to try to solve another complication caused by the Cantonese mandarinate that in February 1630, Rodrigues undertook a new trip to Beijing. Finding himself amongst the Ming again, Rodrigues was involved in military affairs, in addition to the economic ones to which he was already associated. He was tasked, for example, with conducting a recruitment action at the request of the imperial authorities, who placed him at the head of a small military contingent.

It was in this context that in 1631 he was responsible for offering gifts from the Chongzhen Emperor to Jeong Duwon, a Korean mandarin and diplomat travelling with a diplomatic mission from Seoul to Beijing. Rodrigues told him about the work of the Jesuits in the fields of astronomy and other sciences, and presented him with a telescope, which Jeong praised for its power to be used in war. He also gave Jeong a small weapon, a treatise on cannons, and a book on European habits and customs.

As can be seen, the passage of Father João Rodrigues through China did not go unobserved. It should be noted, as a matter of curiosity, that his age was highly speculated. He was estimated to be 250 years of age, and there were many people who went on a pilgrimage to see and touch the Portuguese Jesuit, hoping to receive from him the gift of longevity.

Rodrigues died 1 August 1633, at the age of 71. It was likely the many efforts expended in the military campaigns gave rise to the hernia that ended his life. In a letter dated 4 January 1634, Portuguese Jesuit André Palmeiro who was sent to Macao in 1926 by Rome to oversee Jesuit affairs in Asia, wrote:

“This is due to the lack of care of Father João Rodrigues who did not attend to a hernia in time. The problem worsened and quickly killed him. We are left in great sadness because of his great works and services.”