TEXT: Rafelle Marie Allego and Kary Lam

Today, Macao has a stellar education system – one that has been formed over more than 450 years. We look back at the city’s rich history of learning, teaching and schools.

Influential Chinese philosopher Confucius once said that ‘if jade is not cut and polished, it can’t be made into anything’. What he ultimately meant was that training and discipline are necessary to properly bring up children. Education, as such, plays an important role in shaping society and its people. And no matter how much time has passed, what Confucius said around 2,500 years ago still holds true. Macao is no exception and the city has taken great pride in its education system ever since the arrival of the Portuguese in 1557.

For more than 450 years, Macao – which transferred its administration to China in 1999 – has been massively influenced by many cultures and methods of education. Most influences have come from the Mainland or Portugal, however other Western countries like England have also helped shape the culture. Throughout the years, much of Macao’s educational success has been down to the fact that it has adeptly meshed ideologies and teaching methods from both the East and the West and set up institutions to mirror these influences. This has ultimately cultivated an educational landscape which promotes open cultural exchanges.

While education was once a commodity available only to a select few, learning in Macao is now highly accessible to everyone, with plenty of schooling options available in the city. But before the 1990s, according to the Education and Youth Affairs Bureau (DSEJ), education in Macao wasn’t always guaranteed. We need to go right back to the start of the city to get an accurate picture as to how Macao’s education system formed the way it did and eventually became the successful model we see today.

The early years

As soon as the Portuguese settled in Macao in 1557, the city started growing as more traders set up their homes in the ensuing years. Education would not, on the whole, have been formalised and only children from rich families would have been homeschooled, however, there was a Reading and Writing School established in 1572, which had a Latin class added to it a few years later. It’s said that 200 children – many who were the sons and daughters of businesspeople – were enrolled at the school in 1592. This was just the beginning of a formalised education system, though. The big leap forward wouldn’t happen until 1594 when an institution was set up that would influence Macao’s education system beyond recognition and put it on the global map for higher learning. The first Western university in East Asia opened its doors in that year: St Paul’s College.

Following successful missions into China, Catholic followers of the Society of Jesus – known as the Jesuits – decided they needed a place to teach and train missionaries who would later be sent out across Asia, carrying the word of God with them. They chose Macao and St Paul’s College was born. It was founded by Italian Jesuit Alessandro Valignano and would go on to train countless Jesuits from both East and West. The school model that was used was inspired by Portugal’s University of Coimbra and it focused on teaching science, literature and the arts. Funded by Portuguese businessmen, the college offered a range of courses, from theology, philosophy and languages – Chinese, Portuguese and Latin – to subjects like astronomy and mathematics. “In 1728,” says the Rector of the University of Saint Joseph (USJ), Stephen Morgan, “some of the teaching [from St Paul’s] was moved to the new Royal Seminary of St Joseph.” He adds that St Paul’s College was closed in 1762 and the buildings then used as an army barracks.

Many years ago in Macao, the Chinese had to rely on their own solidarity and efforts to provide themselves with a proper education.

In 1835, after firewood that had been stored in a kitchen in the barracks caught light, the former college buildings burned down. The inferno also claimed the Church of St Paul that once stood next to it. The only remains are the stone façade of the church, now known as the Ruins of St Paul’s. Following the fire, the only higher education institution that was left in Macao was the Royal Seminary of St Joseph, which focused on training missionaries who would head into China. The seminary would much later evolve into the present-day USJ and it still serves as a base for its Faculty of Religious Studies and Philosophy.

Before its untimely demise, the College of St Paul’s successfully introduced Western instruments, books, arts, advanced science and technology, and academic achievements to China. It even contributed to the introduction of Western medicine to China, training Jesuits in the ways of the medicine, according to the University of Macau’s Faculty of Education’s associate professor Dr Cheng Chun Wai. He says that some of the Jesuits even sent medicine to Qing Dynasty ruler Emperor Kangxi as a present.

By introducing these Western teaching methods, books, instruments and medicine to Macao, the college became a major part of the so-called ‘Eastward transmission of Western sciences’ that swept through China at the time. From the 16th century, it helped Macao gain a name for being a place of learning that effectively combined the educational values of East and West.

A tale of two systems

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the education system in Macao was pretty much split in two – children were either taught under the religious Western or the Chinese system. Aside from St Paul’s, for the city’s Portuguese-speaking community, the church played a key role in education. Three churches – St Anthony’s, St Lawrence’s and St Lazarus’ – were prominent at the time as bases for teaching young people. Catholic schools were set up at these sites and literacy classes were instructed alongside the religious teaching, usually on Sundays. The majority of the city’s Chinese population didn’t attend these schools, though, as most of the churches in Macao, right up to the mid-19th century, were exclusively for the Portuguese-speaking population.

At the same time, Macao’s Chinese children followed a totally different education system. Chinese-run schools were set up and the locals took it upon themselves to educate their kids at these establishments. Dr Cheng says that where St Paul’s College was ‘an institution training Jesuit missionaries’, it was ‘not an educational institution for the locals’. “The Chinese had to rely on their own solidarity and efforts to provide themselves with proper education,” he says, noting that this went on until the 20th century and adding that this was ‘especially true during the wartime period in the 1940s’. Dr Cheng also explains that between the 17th and 20th centuries, each wealthy Chinese family in Macao would hire its own teacher to instruct their children in a way that was based on the education system practiced on the Mainland. This system actually differed, whether it was prior to 1644, under the Ming Dynasty, or between 1644 and 1911, under the Qing Dynasty.

In the 19th century, the lines began to blur a little when a spate of religious-based schools started sprouting up for the Chinese population, such as the Morrison School of Macau, which opened in 1839 and is sometimes described as ‘China’s first Western-style school’. Established in honour of Robert Morrison – considered the father of the Chinese Protestant Church – the school used a bilingual education system and taught students arithmetic, geography, history and physiology. However, it moved to Hong Kong in 1842. In 1864, however, the lines blurred even more as the Colégio da Imaculada Conceição opened its doors. This college taught Catholicism to Chinese, Macanese and Western girls all under the same roof. Other subjects that were taught included French and Portuguese. It closed in 1894.

Also in 1894, the Portuguese-curriculum secondary school Liceu de Macau was inaugurated with 31 students – Portuguese, Macanese and children of Chinese government members – on the books at the St Augustine convent, which was based at St Augustine’s Catholic Church in the heart of Macao. After numerous relocations over the following decades, the school’s last building – where the Macao Polytechnic Institute now sits – opened in 1986 before closing in 1999 when most of its students transferred to the new Macau Portuguese School (EPM). It may not be here any more but it was one of the most important school openings of the 19th century.

The biggest changes in Macao’s education system, though, came in the 20th century, beginning with the opening of Pui Ching Middle School in January 1938, at a time when the city’s population was at 68,086 people and only 51.2 per cent of them were literate. This Baptist school, the first school in China to be founded by local Christians instead of foreign missionaries, originated in Guangzhou in 1890 before a second iteration was opened in Hong Kong in 1933. The Guangzhou school was moved to Macao five years later due to the onset of the Second World War – with some teachers from the Mainland fleeing after the Japanese invaded to the relative safety of Macao as a result – and only reopened in Guangzhou after the war, also continuing in Macao up until the present day.

In the early days, the school’s campus was on a piece of rented land at Lou Lim Ieoc Garden in St Lazarus’ parish, a garden which was once part of local merchant Lou Kau’s residence but now serves as a popular public park. In 1952, two prominent parents purchased some of the garden’s land for the school and it has been on that ground permanently ever since. It was officially named Pui Ching Middle School (Macau) in 1950. “At that time,” says the private school’s current principal, Kou Kam Fai, “the vision of education was traditional. But Pui Ching looked for breakthroughs in education, so it developed science and astronomy education, which was innovative in the city.”

For hundreds of years before Pui Ching Middle School opened, Macao had already been offering an education based on a ‘diverse culture of East and West’, as Kou puts it. He says that the school was instrumental in furthering this in the local education system as it innovated new teaching methods and subjects – and this was taken up by other Chinese schools in the city and became part of Macao’s teaching culture. “Today,” says Kou, “thanks to Macao’s rapid development – and with the support of teachers, parents and students – Pui Ching has laid a solid foundation in Macao.” While still maintaining its Christian influences, the school, which has a kindergarten as well as primary and secondary schools, now accommodates an average of 3,000 pupils between the ages of three and 18 years old alongside about 300 members of staff every year.

Other changes for Macao’s Chinese population in the 20th century included the opening of many private Chinese schools. As a lot of parents in the city wanted their children to receive a traditional Chinese education, Macao’s Portuguese-administered government sought to understand and regulate the Chinese-run schools. From about 1910, the church also began putting more importance into Chinese language education and began creating schools – such as Escola Dom João Paulino in Taipa, which was established in 1911 and survives today – that catered to the Chinese population. These schools adopted Chinese teaching methods. During the 1930s and 40s, local Chinese schools were urged to register under the Chinese educational system. Pupils would then be able to receive the Mainland government’s seal on their graduation diplomas.

Sweeping reforms

In the 20th century, there were still two education systems in Macao but reforms happened early on. After the Portuguese revolution in 1910, when the European country became a republic, Portugal went on to reform its government, including the education sector. These sweeping reforms also made their way to Macao. The city’s government centralised early childhood education up to secondary school age, creating a system under the jurisdiction of the main government branch in the Leal Senado building – the ‘loyal senate’ in English, which handled affairs on the main Macao peninsula – as well as the city’s municipal government which handled the remote parts of Macao, principally Taipa and Coloane. These events led to the formation of two schools for the Chinese communities on both islands in 1919: the Escola Municipal da Taipa and the Escola Municipal de Coloane. These schools closed in 1949.

According to the government’s Macao Yearbook, which chronicles events and changes in the city over the years, there were 129 schools in Macao in 1927. Two of them were run by the government, eight fell under the municipal authorities, eight were Catholic and 107 were privately owned Chinese schools – all of them teaching under a single-language curriculum. That leaves four others – each one an important new type of school for the city. Three of these were Luso-Chinese schools, which were created to teach Portuguese pupils both Portuguese and Cantonese at the same time. And the other school was the Associação Promotora da Instrução dos Macaenses (APIM) – Association for the Promotion of Education for Macanese people – Commercial School. This was created to cater for the growing Macanese – predominantly mixed Chinese and Portuguese – population.

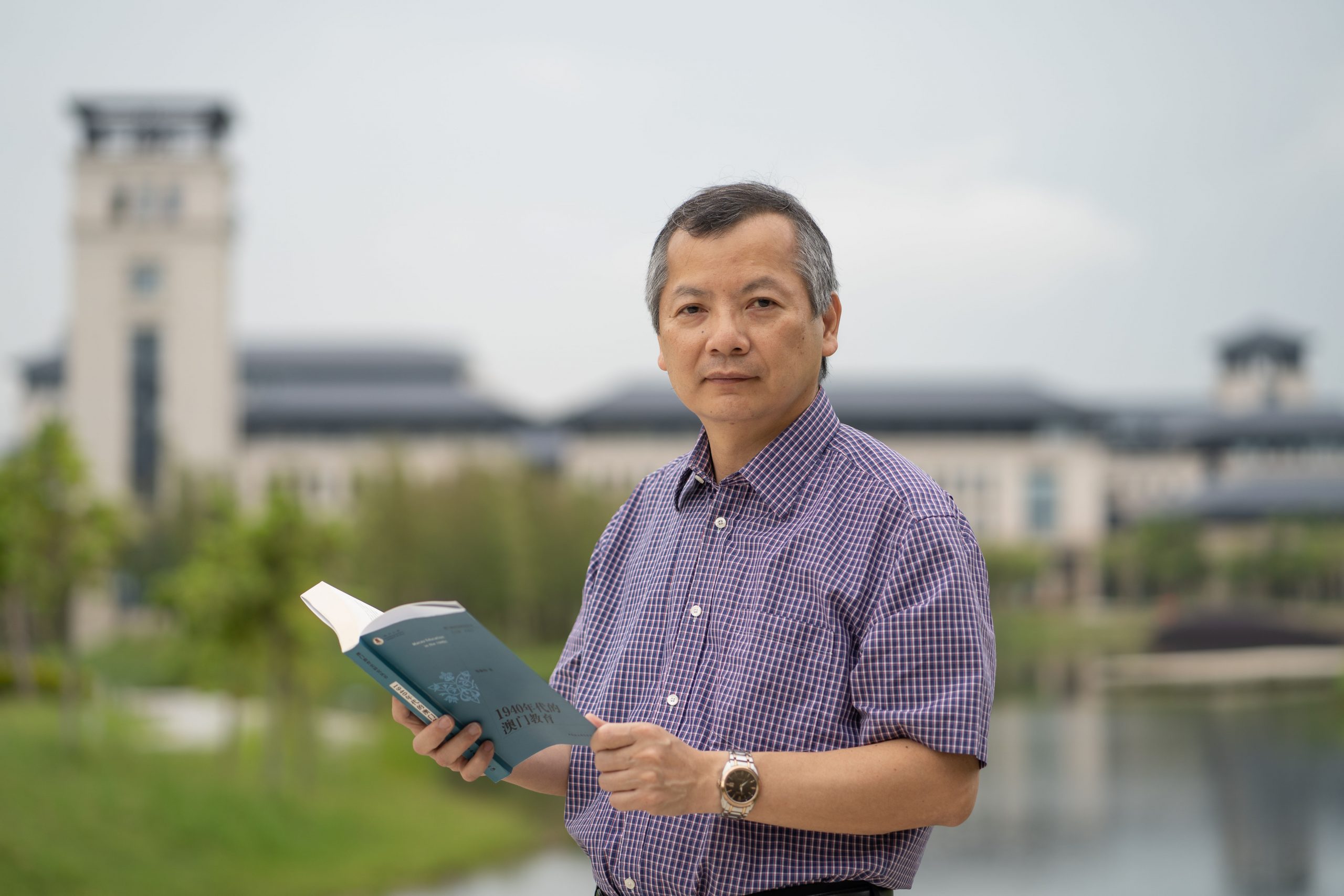

Twelve years on, in 1939, according to Dr Cheng in his ‘Macau Education in the 1940s’ book, there were 112 schools in the city. As schools got bigger in size, the total number fell further by 1952 to 98 schools. Six of them were public – meaning they came under the management of the government or municipal authorities – while the rest were all private or church-run. A total of 22,287 pupils were in education in 1952 – 19,211 were in Chinese-owned private schools, 2,109 studied at religious institutions and just 967 were enrolled in government-run schools.

Over that same period of time, pupil numbers rose and fell on a number of occasions. At the outbreak of the Second World War, when large numbers fled China as the Japanese invaded and headed for the safety of neutral Macao, an influx of children came in and needed to be educated. But these numbers declined rapidly at the end of the war as families returned to China, only to increase again in 1950 with the outbreak of the Korean War when the north and south of the Asian country were in conflict for three years. The Korean refugees in Macao had to be educated but there were many children in the city not in school at this time due to the vast population. This was the same after many refugees left around 1958 as economic depression hit the city. Religious groups, however, stepped in at this time, with Christian churches and charities pouring in resources to help open low-cost schools.

It was not until Macao’s return to the motherland that education experienced a journey from government support to free universal access

Due to those population increases, wars and economic depressions, in the 1950s, 60s and early 70s, many religiously affiliated private schools opened in Macao, including Colégio Mateus Ricci and Chan Sui Ki Perpetual Help College in 1955 and Saint Paul School Macau in 1971. All three survive today. In contrast, in the 1970s, many private schools not affiliated to churches were forced to close their doors as Macao’s birth rate dropped during the decade, causing a decrease in pupil numbers. In 1969, 59,438 children were at school in the city, dropping to 33,935 by 1977. Class numbers fell and schools went into financial difficulties before closing up. Again, the Catholic church came to the rescue and kept its schools open, soaking up local pupils whose school had suddenly shut. “We should be thankful,” says Dr Cheng, “for the elementary education provided for the Chinese by those religious bodies.”

The church in Macao kept up its strong support of the education system in the 1980s. In 1985, the Escola São João de Brito was opened by the Macao branch of Caritas, a Catholic relief, development and social service that spans the globe. Its current principal, Paul Pun Chi Meng, says it was founded in the hope of ‘bringing out-of-school youths back into classrooms’. Also the secretary-general of Caritas Macau, Pun says there were less than 20 pupils at the school, which educates children between the ages of three and 18 years old when it first opened but now there are around 350. He notes that the school is open to children who have faced difficulties in their lives and also says that the school’s motto is to ‘accept all without pre-judgement’.

Other important schools to open in the 1980s included the School of the Nations (SON), a Bahá’í-inspired school that opened in 1988. The Bahá’í faith is a religion that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Macao’s SON opened with just five children enrolled in its kindergarten, which itself was established in an effort to address the need for an English-language school in Macao. By the end of the following academic year, the school was at capacity. As demand continued, the SON started renting out commercial property as it looked for a permanent solution, which came when the government allocated its current space on Rua do Minho in Taipa. Construction began in 2008 and the new school building was ready a year later. As SON’s principal Vivek Nair explains, the school has always been ‘closely reactive to changes in the community’. This means that at the time of their establishment, when Cantonese was being mainly taught in the city, SON was teaching Mandarin. “It’s not just about educating students for one segment,” says Nair, “but educating children for the world.”

It’s worth mentioning that pupil figures for the whole of Macao are available for the 1989/90 academic year, whereas they are not on public record for the rest of the 1980s. In that year, there were 70,518 pupils enrolled in all the city’s kindergarten, primary and secondary schools, and 2,644 students attending the city’s higher education institutions.

A new dawn

On 26 March 1987, the Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration was signed by Portugal and the People’s Republic of China over the status of Macao, establishing the process and conditions of the transfer of administration of the city to China. From this day, in preparation for the 1999 full transfer of administration, the education system underwent a fairly dramatic transformation. Prior to the treaty, the non-intervention policy the Macao-Portuguese government had in place – except in its own government schools – allowed different education systems to blossom. DSEJ director Lou Pak Sang explains that the Chinese accounted for the majority of Macao’s population in the 20th century – as they do now. He says that education for the children of Chinese families before the 1987 declaration was signed ‘was basically undertaken by private organisations or individuals, resulting in a diversified school system and different conditions for running schools’. He adds that these Chinese pupils’ ‘rights to receiving education weren’t guaranteed’ prior to 1987.

The education landscape, after 1987, began to change in preparation for the transfer of administration on 20 December 1999. Lou says: “It was not until Macao’s return to the motherland that education experienced a journey from government support to free universal access.” Lou notes that between 1987 and the moment Macao became a Special Administrative Region (SAR) in 1999, the transition over 12 years had allowed the city to establish its own education system by adopting and learning ‘the education systems of other places’. Following the transfer of administration, in 2000/01, Macao became home to 96 private and 17 public schools and it also had a government that had, over a number of years, put much effort into creating what Lou says is a legal system that supports the city’s education as one entire structure with the ‘construction of education planning and long-term measures’, as well as what he phrases as ‘long-term policy and financial support to guarantee the development of public and private schools’.

When it comes to higher education institutions, one of Macao’s most important moments of modern times also came in the 1980s. The University of Macau (UM) was established in 1981 under its former name of the University of East Asia (UEA). The UEA was a private university with the bulk of students originally hailing from Hong Kong but in 1988, the Portuguese Macao government acquired it and it was renamed the UM in 1991. It was transferred to the new government in 1999 and a new 1.09-square-kilometre campus – 20 times bigger than the original – on nearby Hengqin Island opened in the 2014/2015 academic year. The UM has become Macao’s only public research university. As Dr Cheng explains, up until its establishment, the city simply had secondary schools. “Those looking for higher education would leave to go elsewhere,” he says, adding that those who remained often couldn’t afford to go to university.

The government acquisition of the UEA in 1988 was itself an important moment for higher learning in Macao, according to Dr Cheng. He says at that moment, ‘the government started to take responsibility in providing educational services with the co-operation of some of the local educational bodies as well as the UEA’. This was followed by setting up an education reform committee to address how learning was done in the city at the time, he says, adding that the UEA’s School of Education was established in 1989 – renamed the Faculty of Education in 1992 – to train Macao’s first batch of home-bred professional tertiary education teachers to educate future students. “When we took the entrance exam,” says the assistant dean of the UM’s Faculty of Social Sciences and member of the Macao Legislative Assembly, Agnes Lam, “it was still called the University of East Asia. It was great timing when I entered [the] university since this was the period the Portuguese government started investing in educating more people to prepare for the city’s transfer of administration to China. People from poor families like me wouldn’t have gotten this opportunity if not for the scholarships and discounts being given out, both of which I was fortunate to have received.”

In the 1990/91 academic year, a total of 1,996 students were enrolled at the UM, accounting for all of the tertiary level students in the city. But by the 1995/96 academic year, there were 2,894 students at the UM and, with other higher education institutions opening in that time, there were 6,786 higher education students in the city, showing the massive growth Macao’s tertiary education system experienced in just five years. When the UM was bought by the government and renamed in 1991, though, it technically split into three institutions – the UM, the Macao Polytechnic Institute (MPI) and, a year later in 1992, the Asia International Open University (Macau). This branch was renamed the City University of Macau (CityU) in 2011. Today, the MPI and CityU share the old UM campus in Taipa with the Macao Institute for Tourism Studies (IFTM), which was opened by the government in 1995 and offers degrees in tourism, heritage and hospitality.

The government’s move to ‘take responsibility’ of higher learning in 1988 – and the further work the post-1999 government has done in creating a world-class higher education system in Macao – paved the way for other institutions to open and flourish in the city. The Macau Institute of Management (MIM) was founded in 1988, the same year the Academy of Public Security Forces was established to train the city’s police. Despite evolving out of the old Royal Seminary of St Joseph, the USJ was only officially founded in 1996 before moving to its current main campus in Ilha Verde just three years ago. In 1999, the Kiang Wu Nursing College of Macau (KWNCM) was established, followed by the Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST) in 2000 and the Macau Millennium College (MMC) in 2001. All these institutions stand today, showing quite how far the city’s higher education sector grew in under 40 years.

Dr Cheng says that the whole educational landscape in Macao changed between the late 1980s and the years following the city’s 1999 transfer of administration to China. He says that a law called the ‘Macao Education System’ law in English was passed in 1991 that ‘implemented the framework for the whole of Macao’s educational system’. He says that law was ‘crucial in establishing what Macao’s education is like today’ and, in the years following 1999, he says ‘the government started granting lands to selected groups and institutions to establish new schools in several phases’. According to Dr Cheng, this was done to increase the number of school places at different educational levels. “Financial subsidies to local private schools were also increased,” he adds. This all led to new school openings as Macao’s economy grew, such as the International School of Macao (TIS) and the Macau Anglican College (MAC), both established in 2002 – the former with a Canadian curriculum and the latter as an English-language Christian school.

Over more than 450 years, Macao’s education has come a long way. The College of St Paul laid a foundation for the city to be viewed as a pioneer in education and, throughout the years, Macao has improved its education systems, whether primary, secondary or higher learning. The reforms in the 1980s and the transfer of administration in 1999 were key turning points leading to the creation of a city with world-class higher education institutions and a school system that is inclusive to all and teaches a wide range of East and West subjects, teaching methods and ideologies. As Dr Cheng says, Macao’s hard work over the years in improving its education system meant ‘it was always on a good trajectory to today’s exceptional education system that the city can – and should be – incredibly proud of achieving’.

The scholastic survivors

Macao’s five oldest schools that are still teaching children in the city

Instituto Salesiano

Founded: 1906

Location: Opposite St Lawrence Church on the Macao peninsula

A Catholic primary and secondary school, the Instituto Salesiano is the oldest school in the city that’s still standing today. It’s a member of the Macau Catholic Schools Association and uses English as the basis of its teaching.

Escola Kao Yip

Founded: 1910

Location: On Avenida Xian Xing Hai on the Macao peninsula

Hong Kao Middle School – Escola Kao Yip’s predecessor – was founded in 1910 by the Confucius Association. In 1975, it merged with Ngan Yip Primary School – itself founded by the Macau Association of Banks in 1949 – with prominent Macao businessman Ho Yin as the new school’s founding principal. Today, it teaches kindergarteners through to secondary students.

Escola Dom João Paulino

Founded: 1911

Location: Next to Our Lady of Carmel Church in Taipa

Another member of the Macau Catholic Schools Association, this kindergarten and primary school was established by the Canossian Sisters, a religious organisation of nuns founded in Italy in 1828. They started teaching Catholicism in classes to children at a nearby church from 1895 but these classes expanded into the full school in 1911. Its first intake was 70 pupils.

Yuet Wah College

Founded: 1925

Location: On Estrada da Vitoria in St Lazarus’ parish on the peninsula

An all-boys school founded in 1925, this Macau Catholic Schools Association member serves pupils from pre-school through to secondary. Accredited by the Salesians of Don Bosco Catholic religious organisation, which was founded in Italy in 1859, this school has a long list of notable alumni, including currently serving Macao politicians.

Colégio Diocesano de São José

Founded: 1931

Location: Three campuses: one in Adro de São Lázaro, one in Travessa dos Anjos and one in Rua da Sé, all on the peninsula

The Colégio Diocesano de São José covers kindergarten through to secondary school, with its site scattered across three campuses. It also belongs to the Macau Catholic Schools Association, with its supervisor being Macao Catholic Diocese Bishop Stephen Lee Bun-sang.

Paul Pun Chi Meng

Paul Pun Chi Meng

AGE: 62

ROLE: Secretary-general of Caritas Macau and principal of Escola São João de Brito

STUDIED AT: Instituto Salesiano, then at Yuet Wah College

“When I was a student, I didn’t like to sit down. But compared to the other schools at the time, I was permitted to walk around, make mistakes and think on my feet with the vocational training at the Instituto Salesiano. The education I received developed my creative thinking [and] to have a different perspective. Education should give opportunities to those who need to be given chances. This should be the way for the future of Macao.”

NAME: Agnes Lam

AGE: 48

ROLE: Assistant dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the UM and member of the Macao Legislative Assembly

STUDIED AT: The newly renamed UM in 1991

“It was great timing when I entered university – then still the University of East Asia – since this was the period the Portuguese government started investing in educating more people to prepare for the 1999 transfer of administration to China. As for the future, with universities in Macao becoming more industrialised under the new government, this will help lead to a diversified economy. Fundamental education is also improving, with a recent announcement to make music and art compulsory non-tertiary education. This would equip locals with the knowledge to understand Macao’s own culture and history, as well as their role in the world.”

NAME: Camille Calangi

AGE: ‘Early 30s’

ROLE: Client meeting and reservations assistant

STUDIED AT: Macao Institute for Tourism Studies (IFTM)

“[I was] nurtured through the impulse of economic growth from 2008 to 2012, [when] education grew and better opportunities came with a university diploma – such as the one I have – although luck and connections can also pave the way to a better future.”

NAME: Chloe Wong

AGE: 24

ROLE: Photographer

STUDIED AT: Sacred Heart Canossian College (English Section)

“Besides study, we students were able to develop different kinds of soft skills. For instance, the extracurricular activities programmes [at Sacred Heart] provided lots of opportunities for me to discover my interests during high school. I was a member of the sports club, which was a place for me to learn sports games regulations. I even organised the school’s sports day in order to develop my leadership and communication skills. Books can’t teach us this kind of stuff but these [extracurricular] skills are useful in life.”