With summer afoot, Macao’s art scene blooms, treating the public to a feast of exhibitions that included “Waiting: An Act of Faith”. Organised by a collective of 16 local artists whose works spanned a wide range of media (from traditional oil painting to ship timber to plexiglass), the exhibition was displayed at one of the city’s eminent cultural nexuses: the Tap Seac Gallery.

In its name, “Waiting: An Act of Faith” hinted at the struggle many artists experience during the creative process, when progress is often hounded by uncertainty, doubt, and anticipation. Waiting in this sense is far from a passive state but an active and essential part of the artistic journey.

The exhibition, which ended on 28 May, was organised by the Macau Youth Art Association, an artist-run collective that started out as the youth committee of the Macau Artist Society – an organisation that dates back to the mid-1950s. Due to an increasing number of young artists living and working in Macao, the association became a not-for-profit art organisation in 2019. Today it’s dedicated to nurturing an emerging generation of creative talent and introducing Macao’s art market to their rich realm of output.

Macao magazine caught up with two of the collective’s artists, Lai Sio Kit and Leong Chi Mou, to learn about their creative processes and the work they had on display.

Lai Sio Kit: Painting the ‘city’s skin’

Macao-born Lai had always wanted to become a painter. While the Macau Youth Art Association’s director has never been one to shy away from artistic experimentation (he’s worked with sculpture, drawing, wood blocks and mixed media), Lai specialises in a tried and tested medium: oil painting. He earned a master’s degree in that very field from Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2009, and it’s what he teaches upcoming artists to master today.

“Oil painting is a skill that was invented to depict scenes realistically,” explains Lai, who is in his early 40s. “This medium has a high level of plasticity, so it has never been phased out [by other types of paint]. You create many possibilities with oils.”

To date, Lai has more than 20 solo exhibitions under his belt. His work can be broadly divided into two themes: cityscapes and the natural world. The first is inspired by Macao’s rooftops, in particular those of older buildings with tin sheds perched on their upper terraces. The artist enjoys spending time in these quiet spaces that he says lend themselves to creative contemplation. Their bird’s-eye view they offer also gives Lai an alternative perspective of his home town. “This view is like seeing the city’s skin,” he notes.

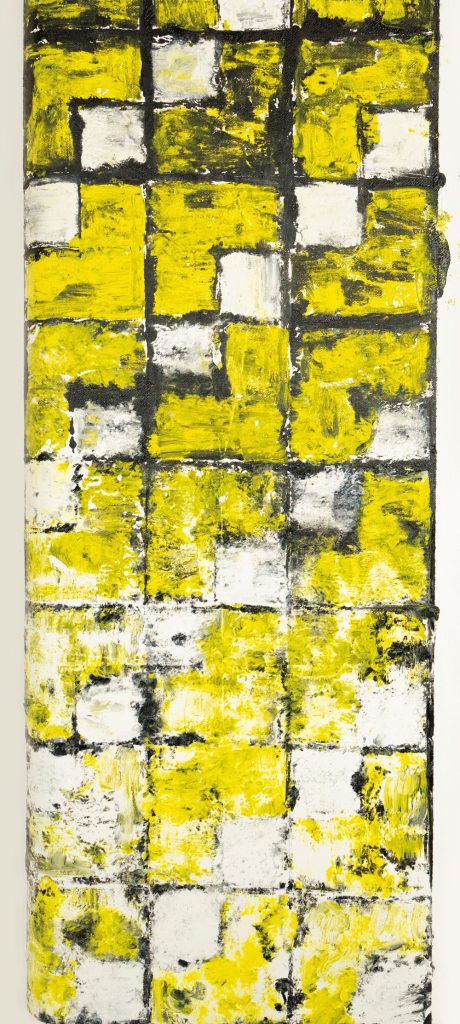

Last year, Lai exhibited his series of tiny abstract oil paintings – thousands of squares resembling the aged tiles that cover so many of Macao’s building exteriors. “They are the patterns of the city; some in the Portuguese style, and some are Chinese,” he describes.

That artwork, titled As Time Goes By, was displayed as a massive mosaic pasted across the host gallery’s walls, ceiling and floor. Viewers encountered an immersive experience designed to make them question the perceived limitations of oil paintings.

“An oil painting is traditionally regarded as something displayed on a wall,” Lai explains. “But could it be extended into a new form of art? For this exhibition, I explored the formats in which oil paintings could be presented. I spread the tiles all over the gallery, hoping to interact with the space [in a new way].”

A love of the natural world

Nature is the painter’s other refuge. An avid hiker, Lai relishes the forests of the mainland, Taiwan and Japan. He also regularly visits Coloane to soak up its green spaces. His nature-inspired art tends to focus on small details. Cloud movements, for instance, or the subtle details of trees.

Lai’s 2023 series titled White Shades came about after a flight over China’s Xizang, during which he’d observed clouds swirling around the mountains beneath his plane. Captivated by what struck him as a kind of cloud choreography, Lai began exploring ways to capture their serene kineticism on canvas.

“The clouds and the snowy mountains offered me a peaceful feel,” the painter shares. “In each White Shades painting, I used one dominant, dark colour, such as blue or grey. Then, on top of that, I detailed my application of various lighter colours to suggest the light in the dark and the movement in still imagery.”

A large artwork from White Shades was Lai’s contribution to the collaborative exhibition displayed at Tap Seac Gallery. It is an arresting painting, with urgent strokes of white paint daubed over a deep blue background, evoking the image of clouds being blown across the night sky. Measuring 2 metres wide and 1.7 metres high, Lai mentioned that it is uncommon to find exhibition spaces in Macao that can accommodate paintings of this size.

Leong Chi Mou’s anti-elitism take on art

While Lai is known for his sombre palette and meditative themes, the artist Leong Chi Mou’s work exudes a distinct playfulness. He uses oil-based paints, but also embraces acrylics, gold lacquer and silver leaf – among other forms of pigmentation. Leong doesn’t limit himself to a traditional canvas base, either. His installations often involve plexiglass, electric wires or household objects.

Leong, in his early 30s, rejects the notion that great art should be the realm of the cultural elite. In fact, he’s on a mission to tear down barriers between art and the masses. Case in point: Some of Leong’s favourite places to find materials for his art are hardware stores and supermarkets, much like his pop art predecessors.

“I tend to use materials that are widely seen in everyday life in my work,” he says. “These materials contain a language. They speak to my practice and also speak to my audience by making art more accessible to the public, not just for the elites.”

Leong’s introduction to art came via television, where he copied traditional Chinese painting techniques from shows as a child growing up in the mainland. He and his family moved to Macao when he was 12 years old and as a teen he began spray painting graffiti-style words on empty walls (with their owners’ permission). That’s when he began seeing himself as an artist.

“It was the first time I realised my work was actually being shown publicly,” he explains. “So, I thought about how to beautify it while also maintaining a radical and rebellious character.” Later, he took up photography. Then he studied oil painting at the Macao Polytechnic Institute’s art school.

Leong enjoys weaving topics of public discourse into his art to make it of the zeitgeist. For example, his 2023 piece Love From Bay Area was a voice-activated fan made out of three vehicle registration plates – one from Macao, one from Hong Kong and one from Guangdong Province. The administrative intricacies of obtaining all three registration plates was a hot topic at time, and Leong says he was curious about the sort of person who could manage it.

‘Good looking but useless’

His work in “Waiting: An Act of Faith” takes the form of a large cabinet made of transparent acrylic plastic and metal. Leong calls the piece Faidoennakel – a take on the Portuguese for ‘made in Macao’ (feito em Macau). He wanted the word to sound like a Western brand, intending it as a metaphor for consumerism in the art world. Leong got the idea while thinking about when, exactly, most people in Chinese society buy artwork. It tends to be when they are furnishing their home, he says. So, they buy art at the same time as functional furniture – as something to fit in with the rest of their decor, not based on its artistic meaning alone. He also owns a Mona Lisa-brand toilet, which struck him as a humorous merging of art and appliances.

Leong’s plexiglass cabinet was made to resemble a style of decorative glass window commonly seen in Macao buildings built between the 1950s and 1980s. The window features a floral motif, more specifically a begonia. According to the artist, these windows are “part of the architectural characteristics of Macao and part of the city’s history.”

Faidoennakel is meant to spark conversations around what art actually is. While the piece looks like a cabinet – ie furniture – it is nailed shut, so not functional. Is that what makes it art? Leong, however, holds no illusions on what his exhibit will most likely end up being used for: a background for selfies, he laughs. “Most people who visit art galleries nowadays just take a selfie and go,” he says. “They seldom stop to think about the artworks’ meaning. So, I’ve created this good-looking yet useless example of both artwork and furniture for people to take selfies with.”

The exhibition “Waiting: An Act of Faith” offered a diverse experience, catering to those seeking selfies, inspiration, cultural enrichment, or new additions to their art collections. The pop artist Leong expressed his anticipation for the local community’s connection with art during the exhibition. Meanwhile, Lai applauded the city’s support for homegrown artists like himself and other members of the Macau Youth Art Association, emphasising the importance of working hard to blaze a trail.