In 1708, a private French trade vessel, Saint Anthoine, arrived in Macao, commanded by an almost unknown captain named Pierre Moirie. The ship did not have any French authorisations, having sailed from Peru – where Moirie had obtained some silver with which he wanted to buy silk and tea in Canton. He also carried a small haul of French crystals and mirrors, items in great demand in southern China.

Moirie arrived in Macao in the middle of the War of the Spanish Succession, six years after Portugal had changed sides – the empire had decided to back England and the Dutch against France. As such, the boat was ordered to leave Macao. Moirie and his crew fled into the Pearl River Delta, then sailed for almost two months in an unsuccessful attempt to reach Canton (Guangzhou). Instead, Saint Anthoine ended up being captured by Chinese war junks and sent back to Macao. Pierre Moirie, meanwhile, only escaped jail through entrusting Macao merchants with his crystalline cargo.

He went on to spend almost a year adventuring between Macao and Canton, which he recorded in his ship’s logbook and – more importantly – on a map. Moirie’s map was, in fact, a rare example of a portolan. This type of nautical chart was an essential tool used by sailors during the Age of Exploration, and featured detailed depictions of coastlines along with helpful annotations. Rather than the lines of latitude and longitude used in modern maps, portolans relied on visual and symbolic elements as well as compass roses to aid in navigation.

Moirie titled his portolan “The Great Bay of Canton” (in French, “La Grand Bahie de Canton”). It inspired many counterfeits, including the works by the famous 18th-century map maker Jacques Nicolas Bellin – official hydrographer for the king of France.

![Carte de La Grande Baye de Canton / J.N. Bellin [counterfeit] (c 1748-1752)](https://macaomagazine.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Counterfeit.-Bellin.-carte-de-la-Grande-Baye-de-Canton.jpg)

However, Moirie was not the first to use the term ‘Great Bay of Canton’. It had appeared as early as 1701, in the South of China section in Michel Antoine Baudrand’s Dictionary of Universal Geography – which was edited in Amsterdam and Utrecht by the geographer Charles Maty. This work was also counterfeited dozens of times during the 18th century, circulating in translations in Spanish and Italian. The notion of a ‘great bay’ was believed to have been established in the 18th century, in several other geographies that sought to be thought of as universal and increasingly commercial.

What these titles all have in common is that they were published in French, by Dutch printing presses – mainly in Amsterdam. Their authors were almost all Protestants and Huguenots, the descendants of French refugees in Holland (sometimes naturalised Dutch), who arrived after the 1581 creation of the United Provinces. Many of these works had the purpose of fueling Dutch maritime and commercial expansion in Asia after the 1602 founding of the Dutch East India Company (the famous VOC) and the opening of the world’s first stock market, in Amsterdam.

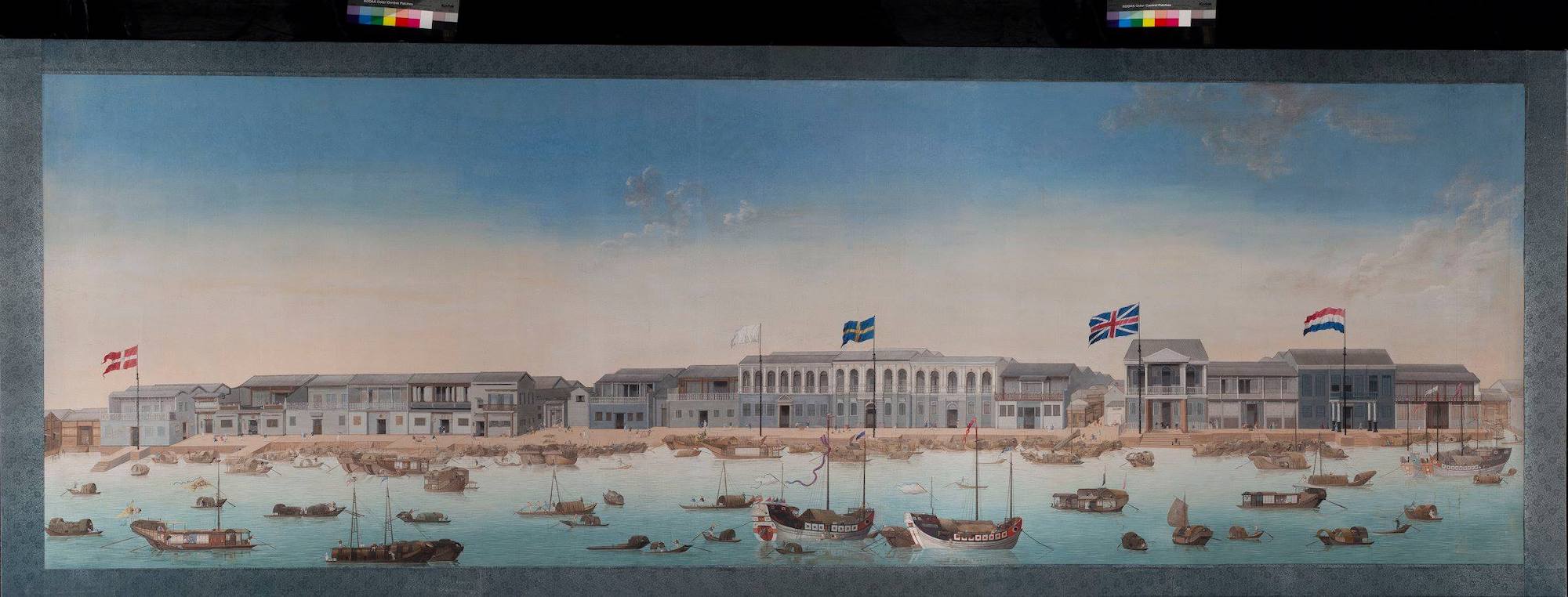

These ‘Great Bay of Canton’ texts and maps were widely disseminated through the large ports of Europe. They all paint a picture of a fundamental commercial space for the world economy between the 17th century and the first decades of the 19th century – that navigators, traders, books, and authors refer to as the ‘Great Bay’.

The Canton system – a trade policy implemented by Imperial China – was in play during this period. It included a commercial monopoly of licensed Chinese merchants, known as the Cohong, who acted as intermediaries between foreign traders and the Chinese authorities. Portuguese sources, including documentation produced in Macao, have referred to the ‘Canton fairs’ since the start of the 17th century. These marked the seasonal opening in the great southern city of negotiations between privileged Chinese merchants – the Hong – with foreign merchants and vessels, originally coming from Southeast Asia, but to which Portuguese and Macanese merchant ships were later added. The Canton system formed a regional world economy with unique trade languages, services, social aspects, and legal resources that relied on the functional relations between Macao and Guangzhou.

The phrase ‘Great Bay of Canton’ was also used by the Royal Company of the Philippines (Real Compañía de Filipinas, in Spanish), which was founded in 1785 under the mandate of Charles III of Spain. The company’s first foreman, the Basque Manuel Gabriel de Agote, was an educated man, a good draughtsman and cartographer, and an ardent supporter of the mercantilist ideas of the Spanish Enlightenment. He was based in Macao – in a large house at the beginning of Rua de Santo António – between 1787 and 1796. Agote left 20 handwritten volumes of his Eastern travels, including the first scientific maps of the Macao and the Great Bay (that he himself had surveyed in detail).

In his business correspondence, Agote wrote this summary, both enlightening and important: “One enters this Great Bay in Macao, where you need to reside most of the year, have many good friends to obtain permits and commercial tariffs, and also a pilot and boats to go up the river to Whampoa, [where you] hire a buyer (a so-called comprador), an interpreter and many servants; everything is very expensive and last year has reached to more than 1200 ‘piece of eights’.”

Referenced to the famous piece of eight – a silver coin also known as real de ocho and the Spanish dollar – began to dominate commercial transactions between Macao and Guangzhou in the late 1700s. Today, Agote’s tally of costs corresponds to well over MOP 200,000. Foreign trade in Canton was expensive, demanding, and closely monitored. Foreign companies and traders had to recruit a pilot in Macao, obtain licence plates, and pay fees and permits. Getting everything in order depended on the various companies, offices, and commercial warehouses located in the city.

Compradores and commercial specialisations

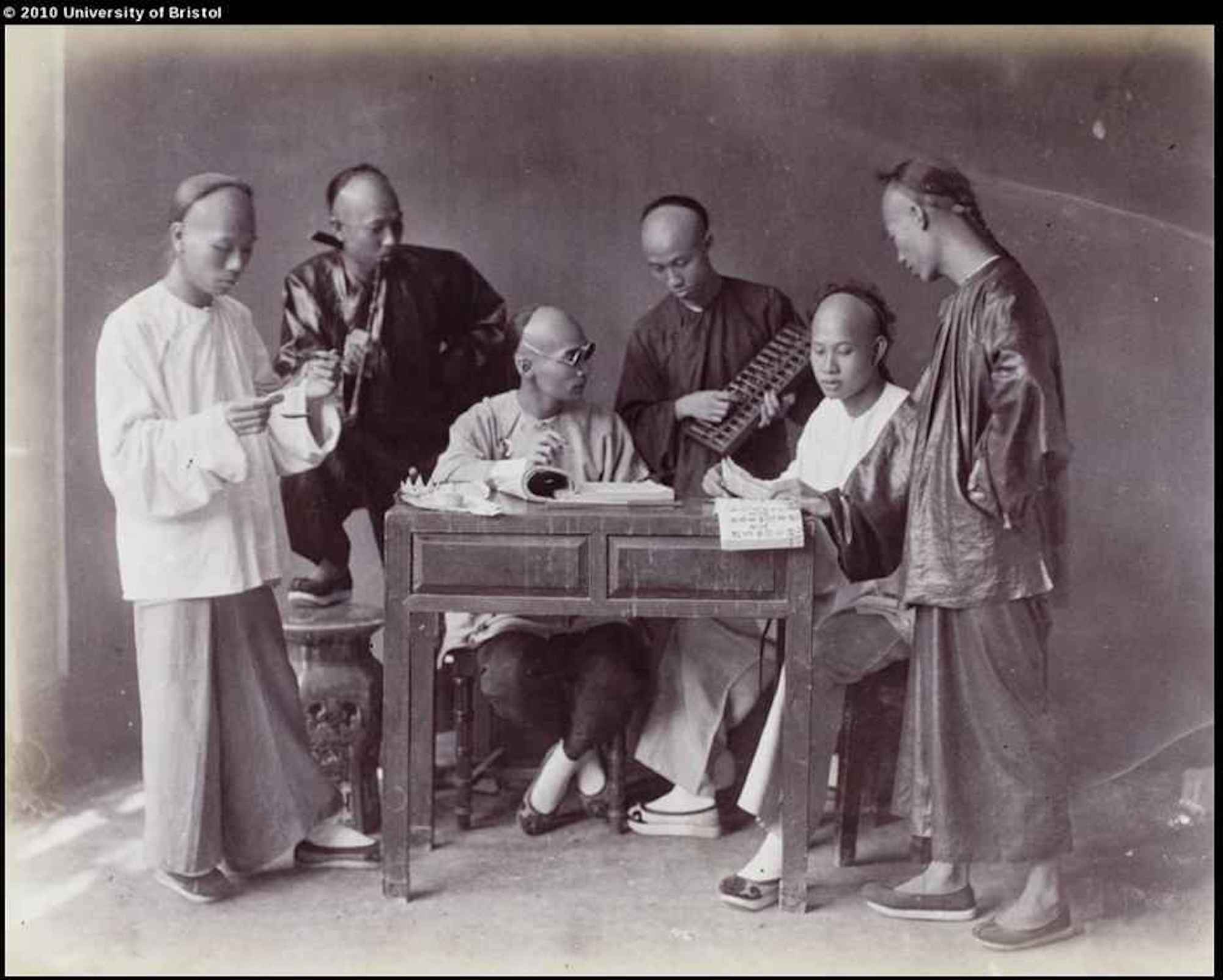

Agote was absolutely correct in his summary. The commercial connections of foreign companies in Guangzhou’s trade relied heavily on the specialised intermediation of enterprises referred to by the Portuguese term ‘comprador’ (in Chinese, mai-pan). These agents were authorised to supply foreign vessels with everything they needed and served as intermediaries in purchase and sale negotiations with Cohong merchants.

Since the beginning of the 18th century, compradores facilitated Chinese agents, Eurasian Macanese, and even some Portuguese merchants to bring together their junks and lorchas through a river trade route to Canton that traversed seven different commercial and customs checkpoints. They mobilised maritime and commercial personnel, interpreters, porters, and many domestic employees. In the final decades of the 18th century, compradores offered trilingual services combining Chinese, Portuguese, and commercial English. The 1842 Treaty of Nanking obliged China to open more ports to British trade, and the comprador concept spread to Shanghai, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and, naturally, Hong Kong.

The profitability of all this trade throughout the 18th century and the first decades of the 19th century was rooted in an impressive collection of specialisations and commercial skillsets present in Macao at the time. For example, Macao accumulated a wide range of offices and commercial warehouses that handled labelling and packaging of imported and exported goods.

Inventories of the vessels belonging to the European companies and private traders that arrived in Macao to prepare for commercial adventures in Guangzhou never featured less than 40 different products – and often reached more than 100. These included textiles and types of rice, as well as the skins of mink, seal, sea lion, and other animals from as far away as from Canada. Shipments purchased in Guangzhou, meanwhile, contained dozens of different Chinese teas, lacquers, porcelain, and other rare goods.

Labels used for this diverse array of products were often trilingual, communicating weights, measurements, and prices in Chinese, Portuguese and English. In the early 19th century, some of the Macao-based labelling companies established their own printing houses in the city. After the Treaty of Nanking, their highly specialised staff were quickly requisitioned by companies establishing themselves in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and the other Chinese ports that had opened to British and international trade.

Legal interventions

Macao was also a base for legal mediators in the Greater Bay – those working to resolve the often thorny commercial conflicts arising between foreign companies, private traders, the Cohong, and Guangzhou’s imperial authorities. Litigation increased in the mid-18th century, when the English East India Company began bringing opium and quantities of impressively manufactured textiles from its Industrial Revolution into the region. Neither product was allowed to be sold on the Chinese market, yet the English forced the Cohong to illegally accept payments in both opium and textiles – making it harder for them to pay other foreign companies’ contracts. This caused some of the Cohong’s most powerful merchants to go bankrupt in the final decades of the 18th century.

In one instance, Guangzhou’s authorities sent the bankrupt Pan Zhencheng – better known as Puankhequa – to Macao for a legal trial that dragged on for more than a year. It ended, in 1784, with Guangzhou accepting the Macao trade court’s solution of reimbursing foreign companies in Chinese products for the following trade season. Another formerly wealthy Cohong merchant, Shy Kinqua (Sekenkua), was depicted by Agote in chains. Sekenkua owed silver to almost all the foreign companies, and Agote wrote in detail about his trail – praising the Macao legal workers involved. The end result was financial intervention from the Viceroy of Guangzhou himself, who provided silver and credit compensations to minimise the foreign companies’ losses.

As a hub for 18th and 19th century international commerce – the place where negotiations took place and deals were done – many foreigners settled in Macao. These were European company representatives, private traders and diplomats, along with their staff and families. They rented the best houses in the city, and brought along their own tastes, entertainment, and games.

Macao morphed into a decidedly cosmopolitan society, boasting libraries, piano concerts, snooker tournaments and the region’s first newspapers. Horse-drawn carriages even replaced the old human-carried palanquins that used to be common in parts of Asia. Depictions of all this can be found in travel literature, memoires, and art of the era – including a painting by the Chinese painter Lam Qua (1801-1860), which portrays the wealthy American trader Nathaniel Kinsman’s luxurious Praia Grande mansion.

The social aspects of life in Macao during this period surely contributed richly to the establishment of commercial alliances and exchange of ideas that brought mercantilist dreams and the first industrial capitalism thought through into the Great Bay.

While what’s now the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area has changed significantly since back when it was known as the Great Bay of Canton, it’s important to acknowledge Macao’s indispensable role in its development – at least up until the Treaty of Nanking was signed in 1842.