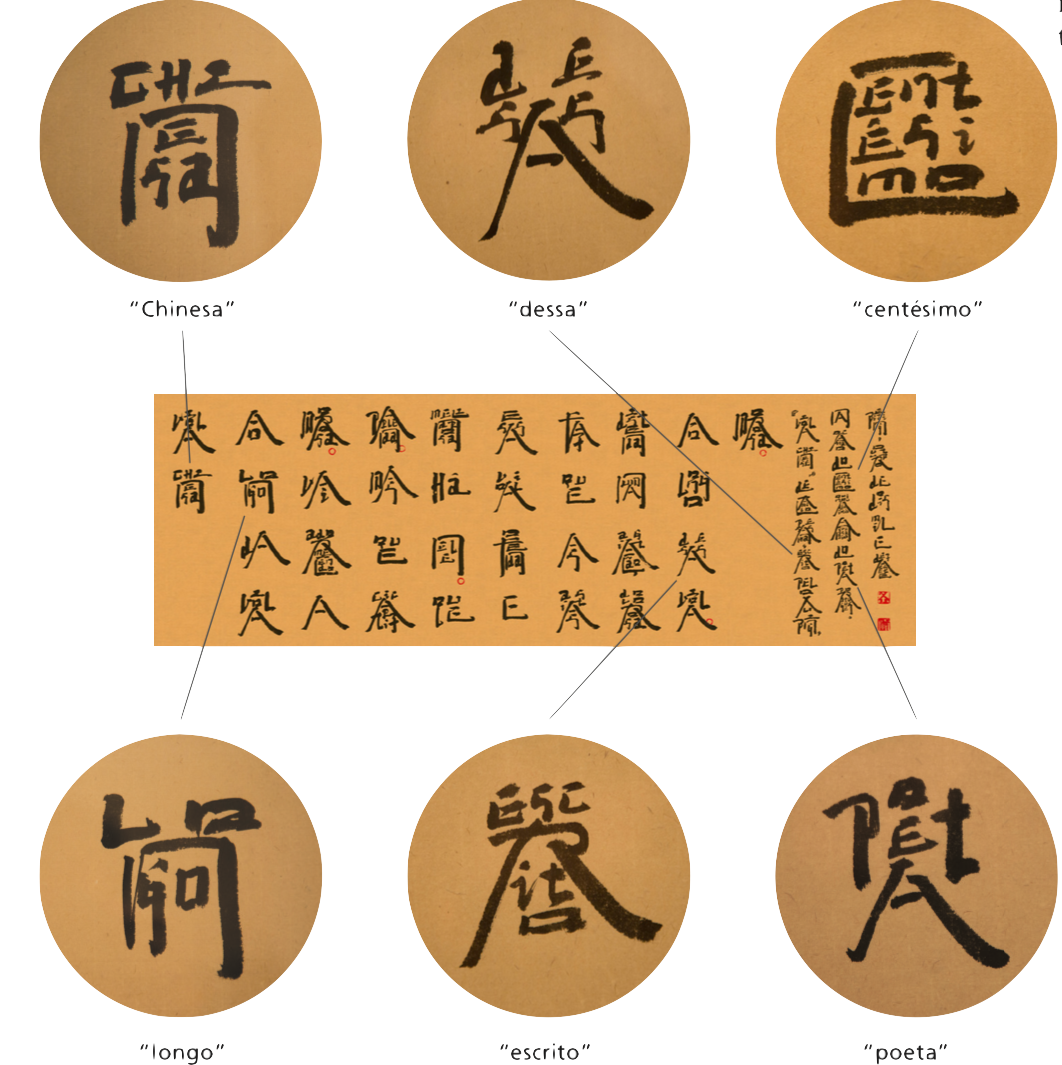

Black ink on brown paper, the sure strokes of an experienced calligrapher rendering one of the oldest written languages in the world. Or is it? Closer inspection reveals the characters are in fact Portuguese words, Roman letters reconfigured and rendered so that each word takes the appearance of a Chinese character. Fitting imagery for an excerpt from Viola Chinesa by Camilo Pessanha, a Portuguese poet who spent much of his life in Macao, itself a compelling blend of Chinese and Portuguese influences.

Hung on the wall of the Macao Museum of Art (MAM), the piece was one of the many striking compositions that made up The Language and Art of Xu Bing. Over its four‐month run, which ended 4 March, the exhibition attracted more than 34,000 people to marvel at the monumental installations, early printmaking, and intimate glimpses into the artistic process of this pioneering figure in Chinese contemporary art.

“They had never seen this kind of work,” said Ng Fong Chao, exhibition project planner; Feng Boyi and Wang Xiaosong were invited to curate the exhibition. “This was the first time that Macao hosted an exhibition on the works of Xu Bing. His is a special kind of modern art. He is a conceptual artist.”

Immersed in characters

Xu was born in Chongqing in 1955, the third of five children. He grew up in Beijing University, where his mother taught and his father chaired the history department. The university and its library was his world – he studied and played there, practised calligraphy, and learned ancient texts and poems.

Xu grew up immersed in the world of Chinese characters – their shape, design, meaning, and resonances – an experience few could claim, and one that would greatly inspired his life’s work.

But this idyllic childhood would not last; Xu was still in primary school when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966. In 1974, he was sent to a tiny village in a mountainous area of north China where he spent the next three years working on a farm along with four other students. They spent long hours working in the fields, but found the time to produce a cultural magazine, Brilliant Mountain Flowers, and printed 500 copies to give out to the farmers.

This simple, if exhausting, rural existence left its own mark on Xu’s work, influencing his imagery and conception of language. The skill demonstrated in Brilliant Mountain Flowers, as well as many banners and posters produced during this period, earned Xu a place at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, where he completed a

bachelor’s degree in printmaking in 1981. He stayed on at the academy as an instructor, earning his Masters of Fine Arts (MFA) in 1987. At CAFA, he mastered the style of Socialist realism that dominated during the Maoist era.

Then he began to create his own works, complex large‐scale installations inspired by the short‐ ‐lived ’85 New Wave movement that ushered in Chinese contemporary art. Two of the best known are Book from the Sky (1987) and Ghosts Pounding the Wall (1990).

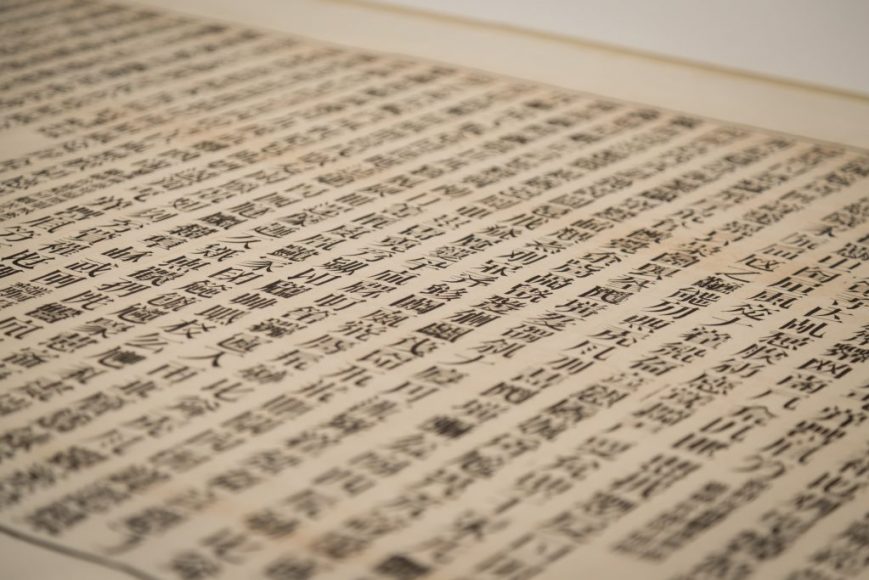

For Book from the Sky, he invented 4,000 characters which he hand‐carved into wood blocks. He then used the blocks as movable type to print volumes and scrolls, which were laid out on thefloor and hung from the ceiling.These large, orderly texts with their traditional style appear to convey ancient wisdom but are in fact unintelligible.

When he unveiled the work in October 1988, seeing so many Chinese characters – the foundation of Chinese culture for centuries – transformed into something meaningless elicited unease and obsession, as some viewers spent hours searching in vain for a readable character. A subsequent showing in 1989 brought more attention to the piece; many artistsand critics consider it the definitivework of the period.

His work also drew scrutiny from the authorities who suspected it of criticising the government. In this difficultatmosphere, he decided, like many of his contemporaries, to go abroad. In 1990, he moved to the United States, where he was invited to work at the University of Wisconsin‐Madison.

He held his first US exhibition the same year at the Elvehjem (now Chazen) Museum of Art on the UWM campus. Simply titled Three Installations by Xu Bing, the exhibition presented Book from the Sky, Ghosts Pounding the Wall, and Five Series of Repetitions, the work that earned Xu his MFA.

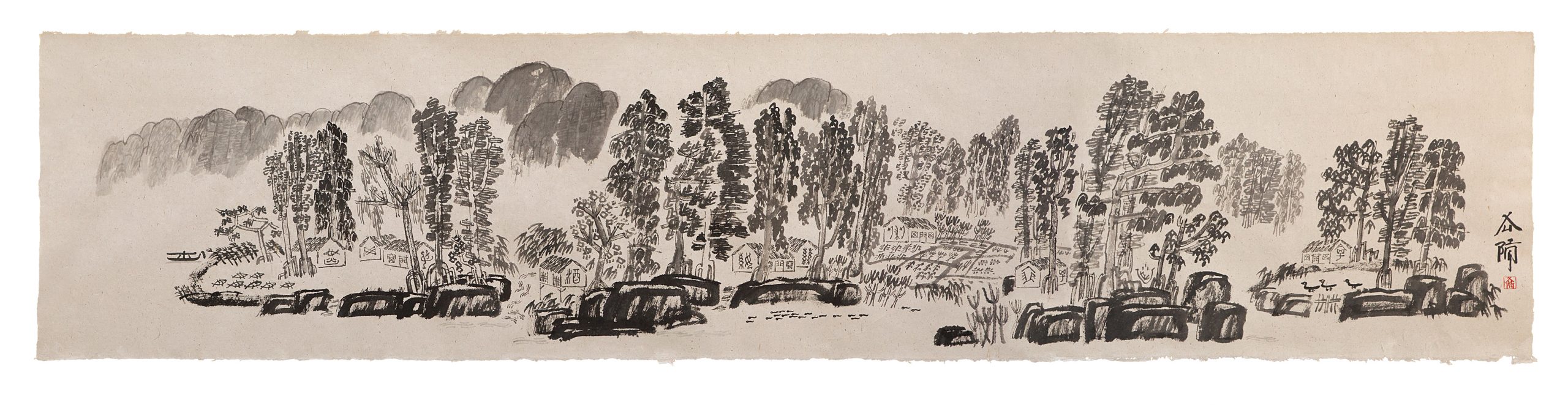

Ghosts Pounding the Wall, a massive 32‐by‐15‐metre work, began while Xu was still in China. Working with a team, it took 24 days to complete the ink rubbings of one section of the Great Wall, and another six months for Xu to stitch together the pieces for display.

An earthen grave mound sits at the base of the “wall,” a haunting allusion to the millions who died in the centuries‐long construction of the actual Great Wall.

In 1994, he began developing a writing system he called “square word calligraphy.” Like his earlier work in Book from the Sky, the seemingly familiar Chinese characters appeared nonsensical to Chinese people – but for English-speakers, there was meaning to be found. Each block organises the English letters of a word into structures that resemble Chinese characters. Xu produced a guide to this square word, or New English, calligraphy and gave lessons in how to write it.

Xu quickly rose to prominence on the strength of his innovative, thought‐provoking work. Major art museums and institutions around the world have displayed his pieces, which have also appeared in two editions of the Venice Biennale, 1993 and 2015, as well as those of Johannesburg (1997), Sydney (2000), and São Paulo (2012). Over the years, Xu has received numerous international accolades, most notably the coveted MacArthur Fellowship, more commonly known as the MacArthur Genius Grant, in 1999, and the Fukuoka Prize for Arts & Culture in 2003.

In 2008, after nearly two decades in the US, Xu returned to China. He became vice president of CAFA, a post he held from 2008 to 2014. Since then, Xu has worked as a professor at the academy and advisor to its PhD students. He remains an active artist, creating new works and holding workshops in his two homes, Beijing and New York.

Coming to Macao

The role of the Macao Museum of Art, according to curator Ng Fong Chao, is to show many differentkinds of art. “On the fourth floor, wehave traditional art from the Palace Museum. Last September, we had calligraphy from the Ming and Qing dynasties. Modern art is also an important part of our mandate.

“In this field, there is too muchchoice – Macao, mainland, and international artists. Each year

we choose a Chinese artist who is internationally famous. Xu Bing is not a typical painter. He is an artist of concepts, who shows a different aspect of modern art,” explained Ng.

Planning for the exhibition began in 2016 with the museum contacting two people very familiar with Xu’s work. “He was very interested and came last year to our museum. This was his first exhibition in Macao. At 63, he is very experienced and knew what he wanted to show.”

The exhibition consisted of 30 pieces, including two of his most famous works, Book from the Sky and Book from the Ground, as well as the experimental trials and rough sketches he produced in the process of creating them. The new Pessanha work marked Xu’s first use of Portuguese in a career defined by a penchant for playing with the plasticity of language.

Specially created for the exhibition, it also served as a tribute to the beloved poet on the 150th anniversary of his birth. The exhibition, spread out over an area of 1,350 square metres on three floors of the museum, made a strong visual impact and gave visitors the opportunity to see the variety in Xu’s work. A reading area offered more than 20 publications related to Xu’s exhibitions, research and writing.

The museum also arranged a series of talks, demonstrations and workshops, enabling visitors to gain a deeper understanding of his complex conceptual works. There were guided tours on weekend afternoons and public holidays after 18 November.

As of 21 January, roughly three months into its run, a total of 34,807 people had visited the exhibition. The majority, 60 per cent, were local while the remaining 40 per cent came from outside the city. As of that day, the 65 guided tours had attracted 1,068 individual visitors and 38 school groups totalling 1,777 student and teachers.

Animal disturbance

Best known for his printmaking and calligraphy, often displayed in monumental installations, Xu has also ventured into the world of performance installations. In 1994, he created A Case Study of Transference, in which an audience watches as two pigs mate in a pen littered with books. Roman letters decorate the boar while the sow appears to bear Chinese characters, but in fact, the symbols are gibberish devoid of any meaning.

It appears a desecration: animals rutting amid the scattered symbols of civilisation – books, language itself – their bodies seeming to sully the text, rendering it meaningless. Originally titled Rape or Adultery?, the piece questions the nature of this base act: is it a violation of the sow with her seemingly Chinese markings, or a welcome betrayal of something else?

In 2017, the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York City selected the piece for Art and China After 1989: Theatre of the World, an exhibition of nearly 150 works from more than 70 Chinese artists. Unwilling to admit live pigs to the museum, they chose instead to use a video of the 1994 performance in Beijing. But intense pressure from animal rights groups, including explicit and repeated threats of violence, led the museum to withdraw Xu’s piece, along with two others featuring live animals, before the opening in October.

By the time the Guggenheim decided to pull the works, an online petition condemning the exhibition had collected over 550,000 signatures. It accused the museum of including “several distinct instances of unmistakable cruelty against animals in the name of art,” taking particular issue with another piece which simulated aspects of dog fighting.

“We usually regard the United States as the country of creative freedom,” Ng said. “Many artists opposed the decision of the museum.”

The video did appear as part of the MAM exhibit; Ng reported that he had heard no such criticism from the visitors to the Macao exhibition. “No one was against it.”