Macao’s first recorded human inhabitants were fishermen, who arrived via the Pearl River Delta from Guangdong in the 14th century. It was they who built the A-Ma temple, which still stands today, and dedicated it to the Chinese goddess of seafarers.

Then came the Portuguese, who traversed oceans in galleons, caravels and carracks – seeking new lands and riches during the Age of Exploration. Macao happened to sit astride one of the world’s busiest trade routes and soon, its harbour filled with ships laden with lacquerware from Japan, Chinese silks and porcelain destined for Lisbon, and spices from Portugal’s colonies in Africa and India.

Later, Macao became known for its talented shipbuilders. That industry went on to fuel the small territory’s economy until the turn of the 21st century.

Given all the seafaring that’s gone on here over the centuries, it’s no wonder Macao is home to a nautically themed museum. The ship-shaped Maritime Museum on Largo do Pagode da Barra was not its first iteration, however. The museum started out in the 1910s, as a simple display of replica boats in what was then known as the Marine Department (now the Moorish Barracks).

Those original models were relocated to the Macau Naval Aviation Centre in 1937. Tragically, just a few years later, they were destroyed when the US Navy bombed the building. It was during World War II, and the US had become suspicious that Macao – a neutral Portuguese-administered territory at the time – was selling aeroplane fuel to Japan (a member of the axis alliance alongside Germany). The US ended up paying Portugal US$20.3 million for what turned out to be an ill-informed raid.

As a result of the attack, Macao was without a Maritime Museum for the next 50-odd years. That changed in 1987, thanks to the city’s harbour master, Commander António Martins Soares. He campaigned for the museum’s re-establishment. It found a home in the so-called Green Building, in São Lourenço, which had previously housed naval officers and their families.

The Green Building was quickly deemed too small, however, and a purpose-built Maritime Museum opened in 1990. The museum’s exterior walls resemble white sails, while its windows are shaped like giant portholes. A moat encircling the distinctive structure represents the sea. Macao’s then governor, the late Carlos Montez Melancia, presided over the new Maritime Museum’s inauguration. Today, its three storeys are packed with model ships, nautical history, and information about the aquatic environment.

Inside the Museum

Visitors entering the museum are met by an enormous sculpture of seafarers aboard a ship; far from the last boat they’ll see. There are, in total, 163 different vessels in the museum collection but not all are on display. One of the oldest is an antique dragon boat carved out of a single piece of whalebone and manned by a crew of miniature wooden sailors. Coloane’s Tam Kung Temple had two whalebones, one which was donated to the museum in 1990 and is more than a century old. Lei Chin Kio, the museum’s senior technical advisor, remembers running her hand along the bone which is currently at the temple during a childhood trip. “They’d say touching the boat gives you luck,” she recalls.

Lei began working at the Macao Maritime Museum in 2019 and is an expert on the Lorcha Macau, a 26.5-metre sailing ship that was built in Macao in the 1980s. The ship was named for a distinctive type of fast-moving vessel developed in Macao around the mid-19th century. Lorchas married Chinese-style sails with Europe-style hulls, and were used up until the early 20th century.

“The purpose of [the 1980s-era Lorcha Macau’s] construction was not only to bring a locally made vessel back to life, that reflected the achievements of Chinese and Western cultural and technological exchanges, but also to serve as a training ship for students who joined the courses of [Macao’s] Maritime Training School,” Lei explains.

The ship sailed extensively around Asia during the 1990s, and was in Portugal at the end of that decade – for Macao’s handover to China. She ended up being scrapped after falling into disrepair in Portugal. Today parts of Lorcha Macau can be found in several Portuguese museums. There’s a model of the ship at Macao’s Maritime Museum.

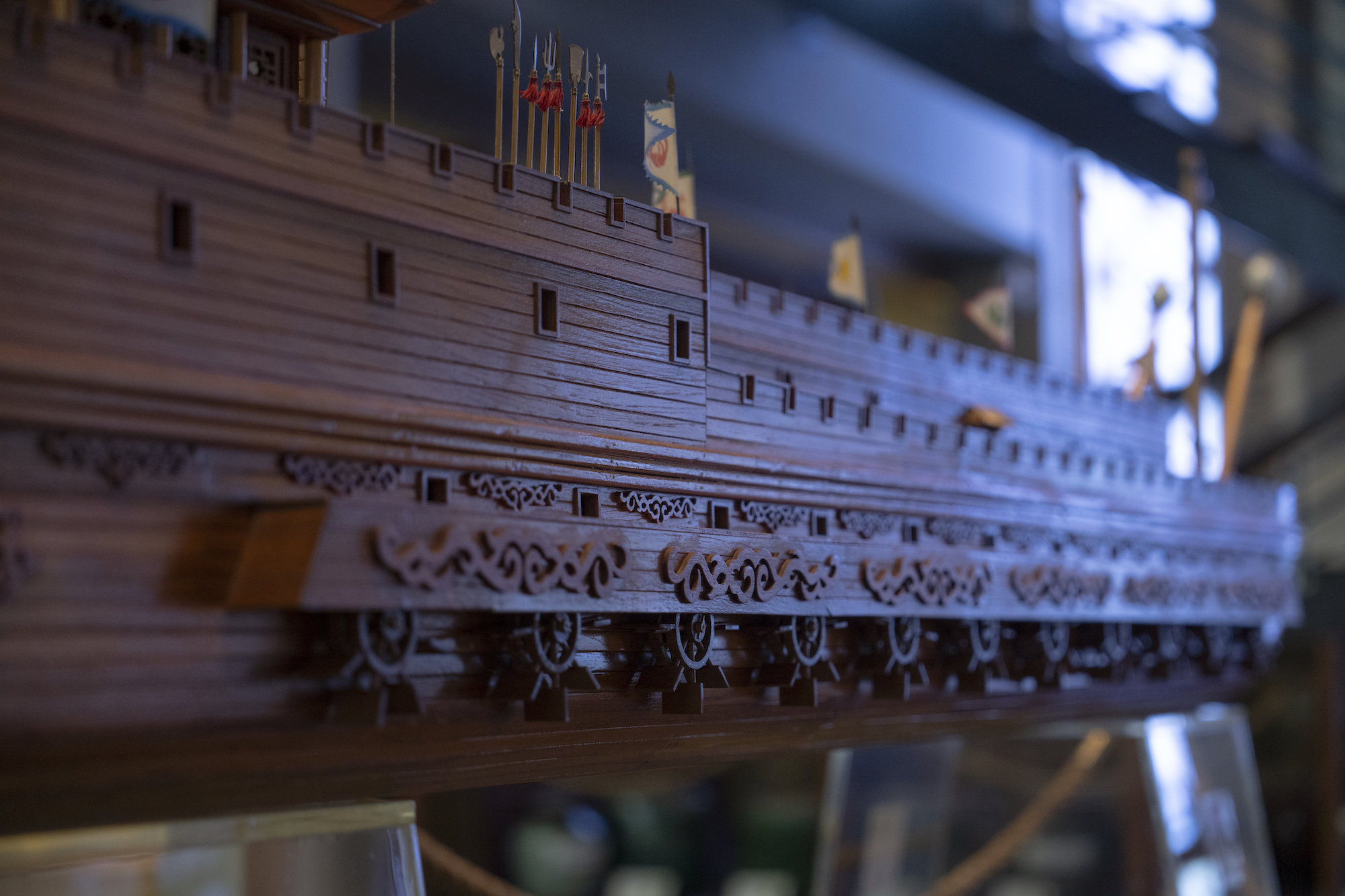

According to Lei, the most impressive model on display is a 1:30 scale replica of a carrack (nau in Portuguese). “It was a large and important ship that sailed extensively between the 16th and 17th centuries,” Lei says. “[Carracks] were used to transport the cargo of silver, silk, and spices and travelled between Goa, Malacca, Macao and Japan.”

According to Lei, carracks were dubbed ‘giant sea monsters’ due to the vast quantities of goods they could carry – up to 2,000 tonnes. Portugal’s most famous explorer, Vasco Da Gama, sailed aboard the carrack São Gabriel on his first voyage to India, in 1497.

Model caravels and galleons – other types of ships favoured by the Portuguese during the Age of Exploration – are also on display at Macao’s Maritime Museum.

The museum pays homage to more contemporary boats too, like the Red Star passenger ship that used to ferry people between Macao and Guangzhou. This 10-hour journey along the Xi River was popular from the 1960s to 1980s; during the 1990s, as roads in the region improved, vehicles replaced vessels as the preferred means of transport.

The man behind the boats

Just two model makers work at the Maritime Museum these days, and one is 60-year-old Tou Wai Lam. He learned the craft after graduating from high school, in the late 1970s, through attending workshops in Guangdong Province.

In 1987, Tou noticed a newspaper advertisement seeking a model maker in Macao; someone to help stock the city’s new Maritime Museum with replica vessels of historical importance. Tou was already in Macao at the time and went for the interview with the harbour master, and was handed a drawing of a lifeboat. The harbour master asked him to construct a replica based on the picture, then and there. “When they saw me building that lifeboat, they knew that I knew what I was doing,” he says. “‘You got the job’.”

Since then, he’s built dozens of replica ships for the museum. His favourite has been a 1:40 scale model of Sagres, a traditionally rigged tall ship that was built in Germany in the 1930s – and later owned by the Portuguese Navy. Tou had actually seen Sagres in person, when she sailed into Macao in 1994. He remembers waking up very early one morning to show the ship to his young son, and take photographs. Those snaps came in handy a short while later, when Tou’s boss asked him to recreate Sagres, from drawings that didn’t even show its colour scheme.

Over the past few years, Tou and his fellow model maker have watched their colleagues retire. Tou himself is reaching retirement age, and he hopes the Maritime Museum will be able to find a replacement for him. Model making is an exacting craft and, according to him, few people these days have the patience for it – let alone the training.

If the museum does find someone before he leaves the job, Tou says he’s keen to share his knowledge and experience. “If the newcomer is interested and devotes himself to learning, he should be able to get good [by the time I retire],” he says.

Parallel to recruiting the next generation of model makers, the Macao Maritime Museum is working to attract a new generation of visitors. It has started offering more interactive activities, like nautical knot tying and shell painting, to appeal to a younger audience. Kids can even learn how to build simple model ships, which they can take home and keep (perhaps becoming inspired to become professional model makers in the process).

“In the past, our exhibitions were still,” Lei says. “Now we have different activities and colleagues who are good at storytelling which attracts visitors.”

Testament to staff’s efforts, between January (when Macao’s borders reopened) and June this year, the museum welcomed about 46,000 visitors. Based on those numbers, it’s on track to surpass 2019’s 58,500 tally – a sign that the city’s maritime heritage is in safe hands.