Every day, adults in Macao use around 160 litres of water. Put another way, that is about 193 Watsons water bottles per adult, per day.

Water is essential to human life and, in Macao, a city surrounded by the sea which depends on outside sources for almost all of its water supply, it is especially precious.

With World Water Day on 22 March shining light on the importance of fresh water to societies everywhere, Macao has plenty of achievements to celebrate, but also many challenges left to solve.

Here is a look at the journey freshwater takes to reach us – from Zhuhai to Macao, from sprawling treatment facilities to tanks atop residential buildings – and what is being done to ensure the taps keep flowing in the future.

From the mainland to Macao

The bulk of Macao’s raw water – water that has not been treated, such as rainwater, groundwater or water from lakes or rivers – comes from the mainland. In fact, about 96 per cent of the city’s water supply is sourced from Zhuhai, according to SUEZ. The French-headquartered water treatment giant runs Macao Water, which provides the city with its clean water.

“We really depend on the mainland,” says Susana Wong, director of the Marine and Water Bureau (DSAMA). “Macao has very shallow water and the Pearl River leaves sand and mud in our water area. Our seawater is polluted and has a lot of sediment,” she adds, underscoring just some of the vexing water security problems Macao faces.

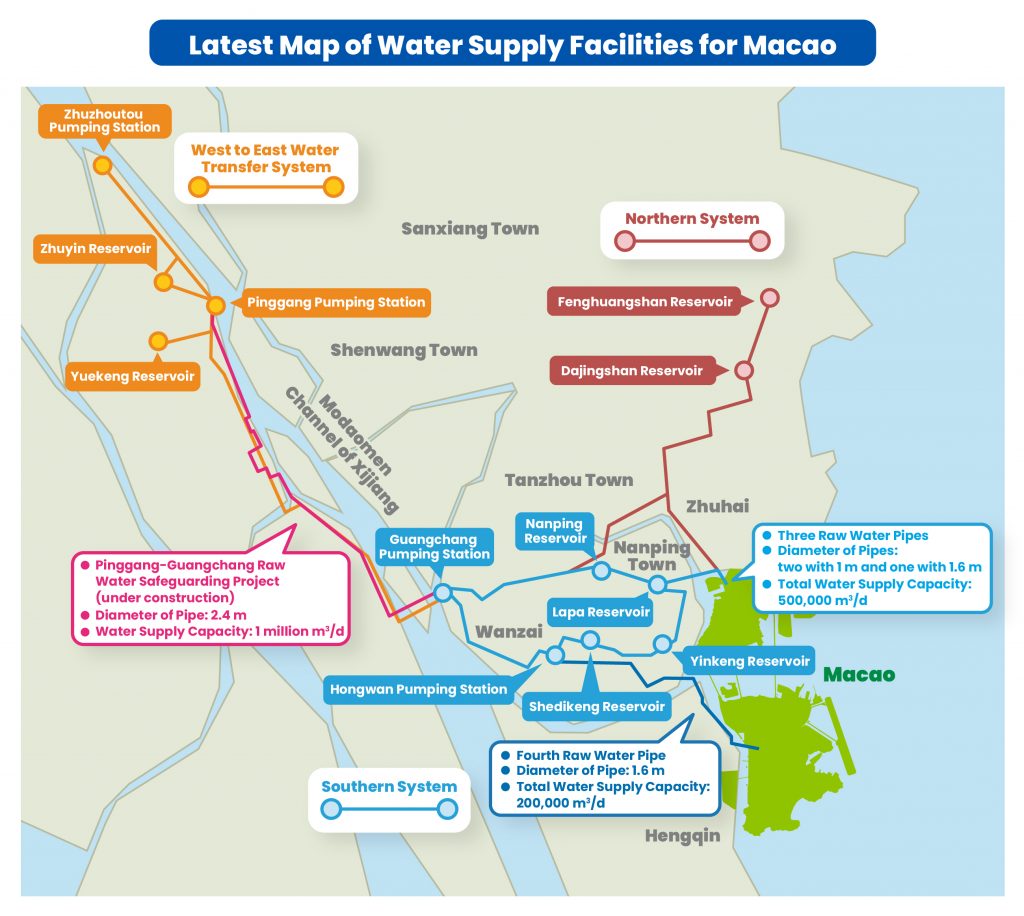

To overcome its scarcity of freshwater sources, the city relies on four pipelines that run raw water from Zhuhai to Macao, where it is filtered, disinfected and distributed to consumers. Three of those pipelines supply Macao with raw water from reservoirs in the northern part of Zhuhai, while one funnels water from a Hengqin Island reservoir to serve the new Seac Pai Van Water Treatment Plant at the end of the Cotai Strip, which opened on 30 November 2021. The plant has since raised Macao’s daily treatment capacity from 390,000 cubic metres of water to 520,000 (1 cubic metre is equal to 1,000 litres). With the city’s population now at nearly 684,000, that supply will help meet Macao’s increasing demands for water for decades to come.

In addition to this sizable new facility, Macao has three other water treatment plants. Ilha Verde and Main Storage Reservoir, or MSR, both treat up to 180,000 cubic metres of water each day. The much smaller Coloane Water Treatment Plant (located on a hill between Hac Sa and Ka-Ho Reservoirs) contributes another 30,000 cubic metres to Macao’s daily supply.

How it’s treated

The raw water from Zhuhai undergoes several stages of treatment before its distribution to consumers. For example, at the Seac Pai Van Water Treatment Plant, raw water coming in from Hengqin Island is mixed with a small amount of water from the Seac Pai Van Reservoir, which is located directly in front of the water treatment plant.

In a process called coagulation, highly charged molecules are added to this water to neutralise fine particles like gravel, sand, algae, clay, iron, protozoa and bacteria. Then a process called flocculation causes these particles to bind together and form large clusters, making them easier to see and remove.

From there, the plant filters the water and adds more coagulants to remove remaining particles, odour and micro-pollutants, as well as to reduce undesirable qualities, such as cloudiness. Finally, the water is disinfected and stored in water tanks, ready for distribution across Macao through the city’s treated pipes.

According to Oscar Chu, deputy general manager of Macao Water, although few people in Macao drink directly from the tap, the company still guarantees the safety and quality of the water it distributes until it reaches individual buildings.

“Once the water goes inside a private property [within residential or commercial buildings], it really depends on the maintenance by the building management, whether they clean the building’s water tank properly, inspect for leaks and [address] rust,” says Chu.

When it comes to water-related issues, most people in Macao are particularly concerned about limescale and the chlorine odour often found in water, both of which, Chu says, are “normal” and “not dangerous.”

Limescale, a sediment consisting mainly of calcium carbonate, often builds up at the bottom of kettles, boilers and hot-water pipework. “Most people find this annoying, but it’s a normal thing. It’s calcium carbonate. It’s minerals. Even if it gets into your glass and you accidentally drink it, it will eventually come out of your system. It happens naturally … Don’t worry about it,” he says.

As for the chlorine found in drinking water, Chu insists that it is “good for disinfection and vital for our water distribution.”

“The closer you are located to our treatment outlet the higher the residual chlorine concentration, so there’s a chance you will smell it when you [turn on] the water tap. But it’s not dangerous, and in fact, it’s vital [for drinking water].”

Macao Water currently distributes treated water directly into the units inside nearly 5,000 low-storey buildings without water tanks. The company also provides water to about 2,000 high-rise buildings. These towers have their own tanks, which are filled with water from the city’s four treatment plants and then distributed to individual units in the building.

Diving into water quality

In order to maintain and improve the quality of the city’s treated water, Macao Water regularly researches everything from water safety to pipelines leakages, virus particles and microplastics (plastic fragments smaller than 5 millimetres long, such as microfibres from clothing and tiny bits of food packaging that pollute water).

Microplastics are found in a range of concentrations in marine water, wastewater, fresh water, food, air and drinking water – both bottled and tap. Although the World Health Organization, citing limited research, has said microplastics pose low concern for human health, a study published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials in 2021 indicates they can damage human cells.

“Because of the spread of Covid-19, we are developing a system to more quickly identify and analyse any virus, microorganism or bacteria [in the water],” says Jacky Lei, another deputy general manager of Macao Water. “We are also trying to develop the standard procedures for assessing the quantity of microplastics in both the raw and treated water.”

Other research projects sometimes require more of a hands-on approach, including literal deep dives into Macao Water’s 630-kilometre pipe network. “[Sometimes] we have to detect if there is leakage. It’s not easy because the pipes are installed underground, so our detection teams must use sensors and listening sticks,” says Lei.

“But our main challenge now is how we can move forward to a digitalised detection system using artificial intelligence (AI),” he says, explaining that the company plans to use existing data and AI to identify leaks more quickly. “That means saving more water, which means saving more energy and [lowering our] carbon footprint.”

According to Lei, the rate of Macao’s water loss due to leakage now stands at about 7 per cent, which he considers normal. In comparison, the mainland loses around 15 to 20 per cent of its water supply due to leakage, while Hong Kong and Singapore lose 15 to 17 per cent and about 8 per cent, respectively, he says.

Mother Nature poses problems

Leakage is just one of many problems Macao Water must account for – some of which, such as natural disasters, are unavoidable.

In 2017, Super Typhoon Hato left some areas of Macao without water supply for one to two hours after a power outage briefly disabled the city’s water treatment plants. Two-metre-high flood water also crippled the Ilha Verde Water Treatment Plant for 36 hours. But the company has since developed solutions to safeguard the city’s water network when a powerful storm inevitably strikes again.

“We quickly built a waterproof gate outside the [Ilha Verde] Treatment Plant [soon after the water receded]. But for long-term solutions, we are looking to install more generators across all the water treatment plants to prevent interruptions because of power outages,” says Nacky Kuan, executive director of Macao Water.

A decade prior, the city experienced record saline levels in its drinking water as severe salt tides plagued the Pearl River Delta in the winter of 2005-06. The salinity level – the concentration of salt in water – reached 700mg per litre, far above the national standard of 250mg per litre.

Due to its location in the Pearl River Delta, Macao experiences high salinity in its water supply every winter, when the salt tides rise higher than the water level in the South China Sea. But Kuan recalls the salinity in the winter of 2005-06 being so potent that people could taste the salt in their tap water. As a reference point, the salinity at that time was roughly four times less than your average bowl of soup, which is 2,000 to 3,000mg per litre on average.

“The central government [had to supply] Macao, Zhuhai and Zhongshan with fresh water released from Guangxi” to meet water demands, she says, adding that while for most people it simply did not taste good, the salty water “might not be good for people with some health conditions.”

After the same problem occurred in 2008, the governments of Macao and the mainland began cooperating more formally on water management practices. Since DSAMA started managing Macao’s water supply in 2013, the city has not experienced any other extreme rises in salinity.

Recycling in the works

While the salinity crises of the past might linger in the city’s collective memory, Wong says that desalination is not the answer to Macao’s water security issues. “For a desalination project we need a big space,” which Macao lacks, she says. Instead, the city is moving forward with a water recycling project – one initially shelved by the local government eight years ago.

Everything should be recycled, including water.

– Susana Wong

“They [local government] will re-study [water recycling]. They are doing some preparations for it, and this recycled water will be used in the new reclaimed areas of Macao, starting with Zone A [the reclaimed land between Macao’s main reservoir and the area where the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge bus terminal is located],” Wong says of the proposed plan.

The project, she explains, will take waste water and recycle it to be used mainly for things like flushing the toilet or watering plants. “It’s a new trend in the world. Everything should be recycled, including water,” she declares.

“We have to use a lot of communication and seminars to teach people that the recycled water can be safely used and [will be of] no harm if it comes into contact with our body. In Singapore, people already drink recycled water. In Macao, this concept is still very new.”

Water recycling is just one of many innovative projects in the pipeline. Two years ago, Macao Water started placing smart water metres inside residential flats in Ilha Verde, as well as some elderly homes and integrated resorts, to research water management and leakage at the household level.

Available in Chinese and English, the smart water metres measured water consumption for 24 hours; if they detected irregularities in water usage, the metres would automatically notify registered customers of a potential leakage via WeChat.

“A normal [person] doesn’t usually use water after midnight because you’re supposed to be sleeping … When the metre detects a continuous flow of water coming from your unit, it means you may have some leakage,” says Chu, noting that the most common source of a leak in Macao households stems from problems with toilets.

Macao Water has laid the groundwork to expand the trial to other areas, with tentative plans to install smart water metres in housing units in Areia Preta’s Lot P next year, followed by some government housing units in the Macao New Urban Zone A in 2024.

In a place where water must be imported, even small toilet water leakages can have a big impact. That makes outside water sources increasingly important, too.

According to Wong, DSAMA is working on several reservoir projects with the mainland that will offer Macao greater water security. As one example, DSAMA is currently funding RMB 800 million (MOP 1.01 billion) for the Dateng Gorge Water Reservoir in Guangxi – also known as Datengxia Dam – which began construction in November 2014 and is scheduled to be completed in 2023.

The reservoirs in Macao are mainly for emergency use only because the whole volume of all the reservoirs can only supply our city with water for seven days,” Wong says. “After Datengxia’s completion, a better control of the water flow from the river will be set up in order to guarantee the security in water supply, whether it’s the flooding season or dry season. If we don’t have enough water, they the Guangxi province will release water down to the areas in the downstream of Pearl River.”

DSAMA holds regular meetings with relevant government bodies across Guangdong province, particularly before the seasons change, to discuss other ways to bolster water security. Currently, Zhuhai is working on more reservoir projects while plans to upgrade the Zhuyin Reservoir are well underway.

“Whenever Guangdong province has such plans or projects, they contact us and we contribute our share,” says Wong. “Recently, we have been cooperating with Zhuhai in the projects for securing the water supply in both cities. Zhuhai and Macao are always working together in the security of water supply for both cities.”