The Macao Museum of Art (MAM) is currently playing host to more than 130 exquisite treasures usually housed between Beijing’s Palace Museum and the famed Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. This unique, collaborative exhibition showcases the art and wares of Tibetan Buddhism’s Gelug lineage – for whom the 15th-century monastery, high up in the Xizang Autonomous Region, holds deep religious significance.

Tibetan Buddhism began playing an increasingly important role in China’s history in the 17th century, as the Chinese Empire encouraged integration with Xizang. The strategic alliances formed between these leaders resulted in the intricately crafted, lavish offerings currently on display in MAM’s “Golden Eminence” exhibition. Each piece was a gift, exchanged between Panchen Lamas (the second-highest spiritual leaders in Tibetan Buddhism) and Qing emperors over the course of several centuries.

The museum’s director, Un Sio San, says “Golden Eminence” celebrates Chinese culture’s inclusivity. Macao marked the 24th anniversary of its return to the motherland in December, and Un says this feels like an appropriate moment to acknowledge the country’s multifaceted cultural makeup. Macao’s own culture, for instance, is a fusion of Cantonese and Catholic Portuguese characteristics dating back to the 1500s. While the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) was founded by northeastern China’s Manchu people, who followed Confucian principles. Then there’s Tibetan Buddhism, which began developing in the 7th century and remains the dominant religion of Xizang today.

“Golden Eminence” is the latest iteration of a tradition dating back to December 1999, when Macao’s handover from the Portuguese administration to the People’s Republic of China took place. Each December, MAM collaborates with the Palace Museum to put on a new exhibition that remains on display right across Lunar New Year (“Golden Eminence” winds up on 17 March). “This show is an auspicious blessing for the festive period,” says Un.

What is the Gelug Lineage?

Founded in the early 15th century by the scholar Je Tsongkhapa, it took the Gelug lineage around two centuries to emerge as the dominant school of Buddhism in Xizang and Mongolia. The Gelug school is also known as the ‘Yellow Hat Sect’ due to the hue of its monks’ distinctive headwear. The word ‘Gelug’ means virtuous; its monks abide by a very strict code of ethics.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the imperial courts conferred official titles to the Gelug lineage’s monks – recognising their spiritual authority in Xizang and Mongolia. This was part of Ming and Qing emperors’ efforts to promote stability across the region through strengthening their political relationships.

The Qianlong Emperor (1711-1799) forged especially close ties with the Buddhist leaders over his six-decade reign. In 1779, to celebrate the emperor’s 70th birthday, the sixth Panchen Lama visited Qianlong in Beijing. Knowing him to be an avid art collector, the Panchen Lama brought with him a wealth of treasures crafted by Tashi Lhunpo Monastery workshops – indeed, birthday presents fit for an emperor. Many of these paintings and statues are currently on display at MAM, in a section of the “Golden Eminence” exhibition titled “Treasures of the Sixth Panchen Lama”.

Realistic and spectacular thangkas

A thangka is a sacred artform in Tibetan Buddhism. They are painstakingly detailed, richly coloured paintings (or embroidery) on silk, typically depicting Buddhist deities or scenes. An exhibition highlight is a thangka titled Tashi Lhunpo Monastery during the Fifth Panchen Erdeni’s Period, believed to have been painted in the late 17th or early 18th century. It’s one of the earliest paintings of the monastery.

The exhibition’s coordinator Irene Hoi Ian Chio thinks very highly of this piece. “The size is not huge, but it demonstrates a very high artistic level,” she says. The top of the thangka depicts the fourth Panchen Lama’s towering mchod-khang (a chapel which still stands to this day) and residence. Dozens of robed, yellow-hatted monks fill up the rest of the painting. They appear to have been captured at a moment of energetic discourse, each with a different expression on his face.

Chio points to the “magnificent” work’s meticulous brushstrokes, noting that viewers can “see the lifelike depiction of monks debating scriptures.”

The 15th-century thangka master Menla Dondrup spent many years at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, studying Buddhist doctrines and teaching art while there. He founded one of the three major thangka painting schools, called Menri. It is known for its Persian influence and attention to tiny details. Later, in the 17th century, a ‘New Menri’ style developed with elaborate colour schemes and an emphasis on curves.

Both old and new Menri styles can be glimpsed in “Golden Eminence”. A 16th-century work titled Arhat Bakula is an example of the former, while the 19th-century thangka Shakyamuni Buddha, Eight Arhats, Hvashang and Two Celestial Kings belongs to the latter.

‘Purple gold’ statues for the soul

Along with paintings, Tashi Lhunpo Monastery’s craftsmen are famed for making fine statues, or tashilima, out of copper, brass, gold and a special alloy called zi-khyim (which translates as ‘purple gold’ in Chinese). Zi-khyim statues have a dark, purplish surface that shimmers with iridescence and are said to emit multi-coloured rays of light. The alloy is only made in two places: the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the capital of Xizang Autonomous Province, and Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. At the latter, zi-khyim is made in the Tashikitsel and Cupusi workshops.

The sixth Panchen Lama brought zi-khyim statues with him on his journey to Beijing, where they greatly impressed the Qianlong Emperor. Tashilima depict Buddhas and bodhisattvas (people who strive to attain buddhahood). They are objects of reverence, but also serve as aids to meditation and conveyors of spiritual teachings.

Golden Eminence features aparticularly beautiful tashilima of a cross-legged Shakyamuni Buddha (the original Buddha). His body and thin kasaya (robe) are made out of zi-khyim while his head is gold. A turquoise stone has been inlaid into the statue’s base. This Buddha is performing the ‘land touching’ gesture with his right hand, representing the moment when the Earth witnessed his enlightenment.

Gifts to be treasured – but also embellished

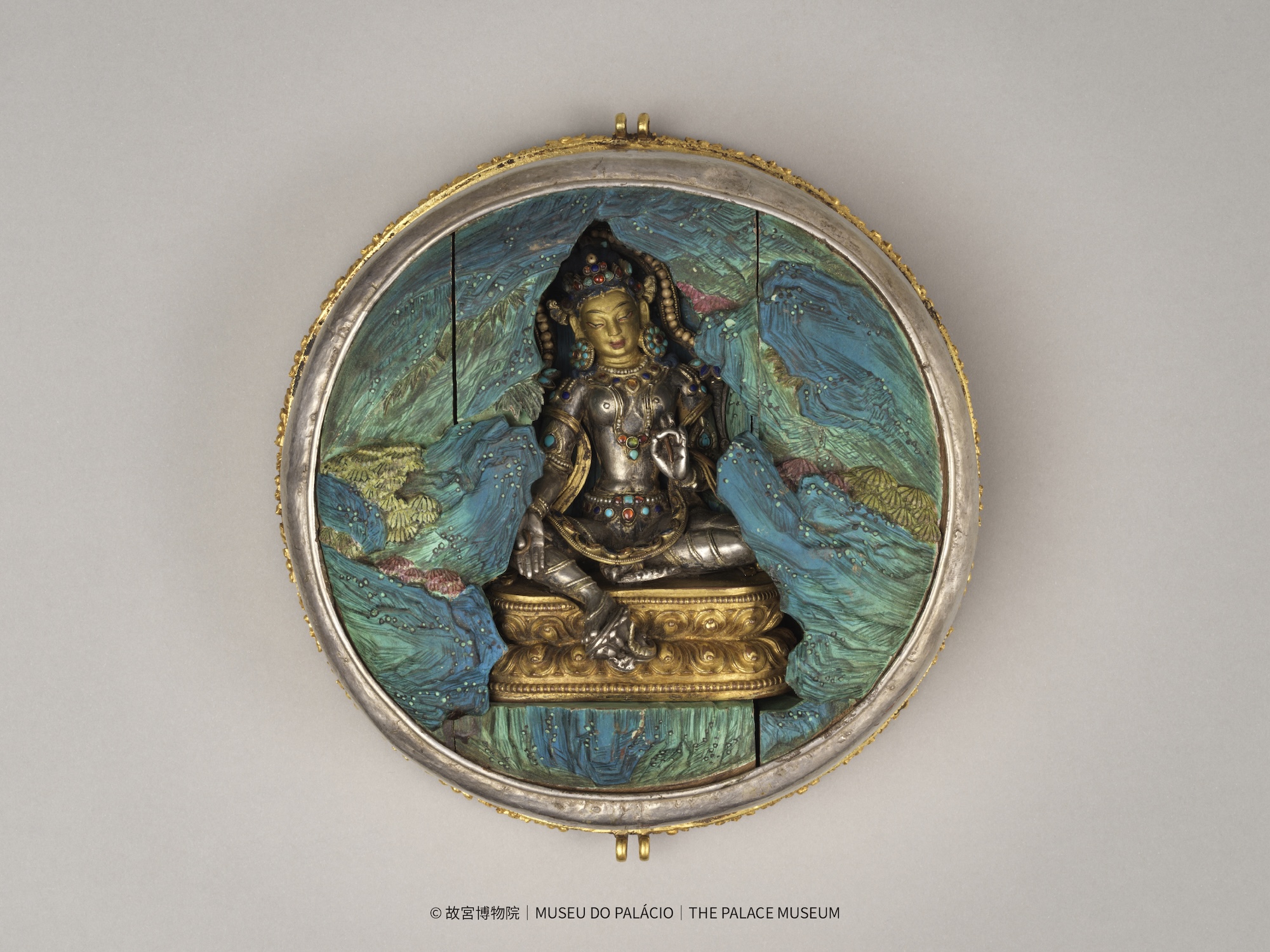

Another exhibited gift believed to have been highly prized by the Qianlong Emperor is an unusually large amulet box made of gold and inlaid with gemstones. Used by Tibetan Buddhists as portable shrines that housed small statues of deities, amulet boxes are worn around necks or across the shoulder. “This amulet box is incredibly luxurious and blissful,” enthuses Chio, who describes it as “giving off a brilliant, shining effect.”

The deity inside this amulet box is a Green Tara, a manifestation of the bodhisattva of compassion’s tears. According to Chio, Green Tara’s wisdom and empathy is especially evident in this example of Gelug craftsmanship. “Take a closer look; the artistic beauty and the power of compassion will blow you away,” she urges.

While Tibetan Buddhist objects were highly valued by the Qing Imperial Court, they were also occasionally embellished by the court workshop. Take the tashilima of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara Amoghapasha, which is on display in Golden Eminence. This 28-centimetre-tall, four-armed figure started off as “a typical statue made in Tashi Lhunpo Monastery,” explains Chio. After being gifted to the emperor, the Qing Imperial Workshop added an embroidered garment bejewelled with rubies and sapphires. The garment is adorned with the eight auspicious emblems of feng shui, along with ocean waves – imagery typical of Qing court productions of the time, though certainly not of the Tibetan Buddhists from landlocked Xizang.

The court also crafted a red sandalwood shrine, with a glass door, for the tashilima. This depiction of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara Amoghapasa is not only extremely rare regarding its bi-cultural creation, but also for the fact its subject is holding four implements used in Buddhist rituals. “The statue is extremely exquisite and the garment is vulnerable,” says Chio. “This is surely a unique opportunity to see them at the exhibition.”

Celebrating the diversity of Chinese culture

The “Golden Eminence” exhibition is a rare chance to see these artefacts, many of which have never left the mainland. Even for people who have travelled to Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, which sits at an impressive altitude of 3,800 metres, few have laid eyes on the meticulously crafted pieces usually housed there.

Indeed, the exhibition is proving popular: between mid-December and early January, more than 8,500 people visited MAM to admire the precious treasures. Beyond the physical objects themselves, the stories behind each object only add to their appeal. Each one has been held by and admired by emperors, and travelled thousands of kilometres over land between Xizang and Beijing.

“Golden Eminence” is not just for looking at. MAM is committed to art education, its director says, noting that the museum is hosting workshops, lectures and performances to introduce elements of Xizang and Tibetan Buddhism’s culture throughout the exhibition period. These are an opportunity to learn about ‘singing bowls’, for instance, which are shaped like inverted bells and used for music therapy. When a mallet is rubbed around the bowl’s metal surface, it produces an ethereal, vibrating sound that Tibetan Buddhists associate with deep relaxation.

“Macao, Beijing and Xizang have different customs and religions, but all are excellent examples of Chinese cultures,” says Un. “This exhibition connects them and allows them to share a strong ethnic bond.”