Lo Seng Chung’s earliest memory of setting foot inside the Foc Tac Temple is as a boy of about 9 years old. Now 65, the businessman recalls following his grandmother through its entrance to pay their respects to Tou Tei, the Earth god in Chinese folklore. This memory isn’t just of the rituals they performed that day, Lo tells Macao magazine. He can still taste the much-anticipated treat that followed: barbecued pork, prepared as an offering to the deity.

Foc Tac, in Macao’s historic Horta da Mitra neighbourhood, has always been a pillar of Lo’s world. His grandfather ran a camera shop nearby, and his friends all lived in the area. As time moved on, Lo himself became an integral part of the organisation that manages the temple, the Associação de Beneficência Foc Tac Chi ou Tu Ti Mio de Macau.

In the 1990s, he started organising traditional Cantonese opera shows for Foc Tac’s annual Tou Tei festivities – a series of events celebrating the Earth god’s birth. The biggest of these is the Feast of Tou Tei, always held on the second day of the second lunar month.

When Lo was made president of the association in 2008, he enlisted his childhood friends – some of them retiring civil servants – and formed a “small but dedicated team” to help him. “Our neighbourhood may be small, but our bond is strong,” he says.

Other examples of Tou Tei customs include burning incense and making offerings to him before launching a new venture or moving house. As president, Lo spearheaded efforts to get traditions like these formally recognised as part of Macao’s intangible cultural heritage. This year, he was designated Tou Tei beliefs and customs’ ‘representative transmitter’ by China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

The designation honours his role as a custodian of tradition and the decades he has spent keeping Tou Tei worship alive in modern Macao. For Lo, that work is rooted in what he witnessed growing up. “The Tou Tei customs in Horta da Mitra were always present,” he recalls. “You could see the deity’s influence everywhere – on street corners, at shop entrances. It shows how much the people of Macao value him.”

From harvests to high-rises

Tou Tei traditions have deep agrarian roots in Chinese folklore. In ancient China, people believed that every plot of land had a spiritual guardian controlling its fertility. Over time, these spirits merged into a more formalised deity: the Earth god, who farmers worshipped with offerings and prayers, asking for bountiful harvests and protection from natural disasters. He’s called Tou Tei (土地) in Cantonese-speaking regions like Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and Macao. Elsewhere in China, he is better known by his Mandarin name, Tudi Gong (土地公).

As Chinese society urbanised, Tou Tei’s role expanded beyond agriculture. He became a guardian not just of land but of homes, businesses, construction sites and entire neighbourhoods. Across the ages, people from all walks of life have sought Tou Tei’s aid. Reverence remains especially strong in southern China and among overseas Chinese communities. In Macao, stone tablets and small shrines to Tou Tei can be found at street corners, beneath banyan trees and at the entrances to buildings. Residents these days turn to him for everything from securing safe construction to smoothing squabbles within communities.

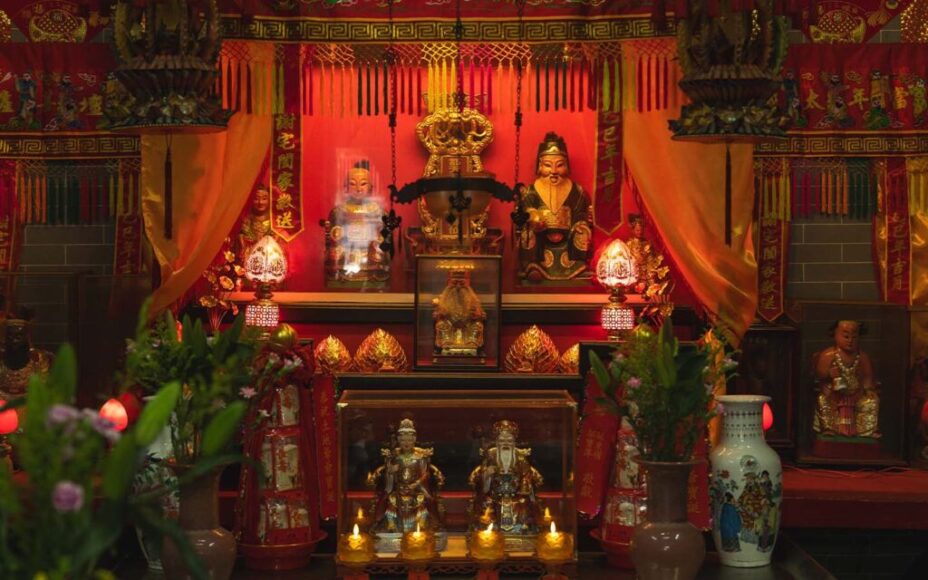

Tou Tei is typically depicted as a kindly, bearded old man carrying a walking stick. He is occasionally accompanied by his female counterpart or consort, an elderly woman known as Tou Tei Po, the Earth goddess. Tou Tei’s iconic image appears in the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West, published during the 16th century, as well as in its many adaptations in film and television.

Macao alone is home to over 160 small altars and tablets dedicated to Tou Tei, and 10 fully fledged temples. Of the three major Tou Tei temples, the oldest was built during the reign of Qianlong Emperor, in the 1700s, in Macao Peninsula’s historic Pantane area. The second was established a little further south, in 1868, on Rua do Almirante Sérgio. The Foc Tac Temple is the youngest, built in 1886.

Protecting Tou Tei for future generations

In the 2010s, Lo watched as examples of Macao’s intangible cultural heritage, like Cantonese Naamyam (Narrative Songs) and the customs of Na Tcha, were added to the National Intangible Cultural Heritage list. This motivated him to seek local recognition for Tou Tei.

“We just wanted acknowledgement from the Cultural Affairs Bureau, as our annual festivities attract many participants,” he recalls. The association formally announced its intent to push for ‘The Belief and Customs of Tou Tei’ to be inscribed in Macao’s Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage during the 2015 Tou Tei festival.

The approval process took two years and involved extensive documentation, community engagement and meetings with authorities. Finally, in 2017, Tou Tei culture became part of a precious collection of customs, arts, rituals, festivities and crafts safeguarded under Macao’s law, ensuring they’ll be passed down from generation to generation.

Onto the national stage

Though it hadn’t been the plan at the beginning, Lo and other Tou Tei advocates soon began to dream bigger. Ramping recognition of Macao’s Tou Tei customs up to the national level would not only elevate the deity’s standing in the country, they reasoned, but help showcase Macao’s unique identity.

The three major Tou Tei temples convened. Since any application for national cultural heritage status must come from a single entity, Lo’s association was chosen to represent them. He says he feels deeply grateful for the trust placed in him by his peers.

Achieving national recognition is no small feat. To get there, Lo and his team collaborated with the Macao Polytechnic University’s Centre of Sino-Western Cultural Studies, led by the now-retired Professor Jiang Chun, along with the Oral History Association of Macao. Together, they compiled extensive audio interviews, photographs and written records about the beliefs and customs of Tou Tei.

Their collective efforts paid off. In 2021, Tou Tei’s cultural legacy was added to the National Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Lo sees the moment as celebrating the power of small but determined communities, united for a cause.

Bigger, and better

Since then, the city’s Tou Tei associations have continued to organise community events like Cantonese opera performances and banquets for the elderly. Having Tou Tei become part of China’s national intangible heritage has certainly increased their exposure, says Lo, and that’s been a boon for the coffers. Donations come from regular worshippers, local celebrities and figureheads, and the government. “It’s a positive cycle – more support leads to better outcomes,” he notes. At the most recent Feast of Tou Tei, the Associação de Beneficência Foc Tac Chi ou Tu Ti Mio de Macau set a new record: 105 banquet tables lined the streets, each seating up to a dozen guests.

In an attempt to raise cultural awareness among younger generations, the association has collaborated with local creative brand Veng Lei Laboratory to design a contemporary fu talisman featuring Tou Tei. Originating from Taosim, these talismans are rectangular, yellow pieces of script including incantations and symbols perceived as instructions for deities or spirits.

According to Lo, around 20 young volunteers took part in 2025’s annual Tou Tei festivities. He believes their enthusiasm signals a promising shift toward youth involvement in heritage preservation.

This year also saw Lo officially appointed by China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism as a national-level representative transmitter of intangible cultural heritage – one of just two people from Macao selected in the latest round. A statement issued by the SAR’s Cultural Affairs Bureau in March outlined the laborious process behind this special status, and noted that only nine people from Macao have been appointed to date. It highlighted Lo’s tireless efforts to keep beliefs and customs of Tou Tei alive, describing them as providing residents with a “sense of belonging and spiritual connection to the land on which they live” and “an important manifestation of Chinese traditional culture in Macao.”

Lo says it was a deep honour to be a representative transmitter. “I never imagined receiving such a significant title,” he reflects. “Our focus was simply on applying for Macao’s intangible cultural heritage; even national recognition was beyond our initial expectations.”

Looking ahead, Lo hopes Tou Tei’s legacy will continue to strengthen Macao’s sense of community. To maintain this, he believes in preserving Tou Tei traditions through highlighting their cultural significance rather than their religious aspects. By focusing on how the ancient Earth god connects people and reinforces local identity, Lo has faith that Tou Tei will remain relevant to younger generations.