As one of the most renowned scientists in your field, what motivated you to accept, in 2016, the invitation from the Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST) to establish a laboratory in Macao?

Well, I first came as a visitor, giving a lecture at a scientific meeting. Then I was invited again and received an honorary [Doctor of Science] degree from this university [in 2016]. I realised that there was research being carried out at a very high level on substances from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). In a way, I had always been interested in TCM. Given my background in research on ion channels in cells, of course, the issue came up: ‘Maybe there are very interesting substances that can be discovered by analysing TCM formulations, which influence the functioning of ion channels’. In particular, there is one type of ion channel very important for immune regulation, yet relatively little has been known about substances that influence it. One of the ideas was to find substances from TCM libraries that would affect that channel. So that was my first motivation.

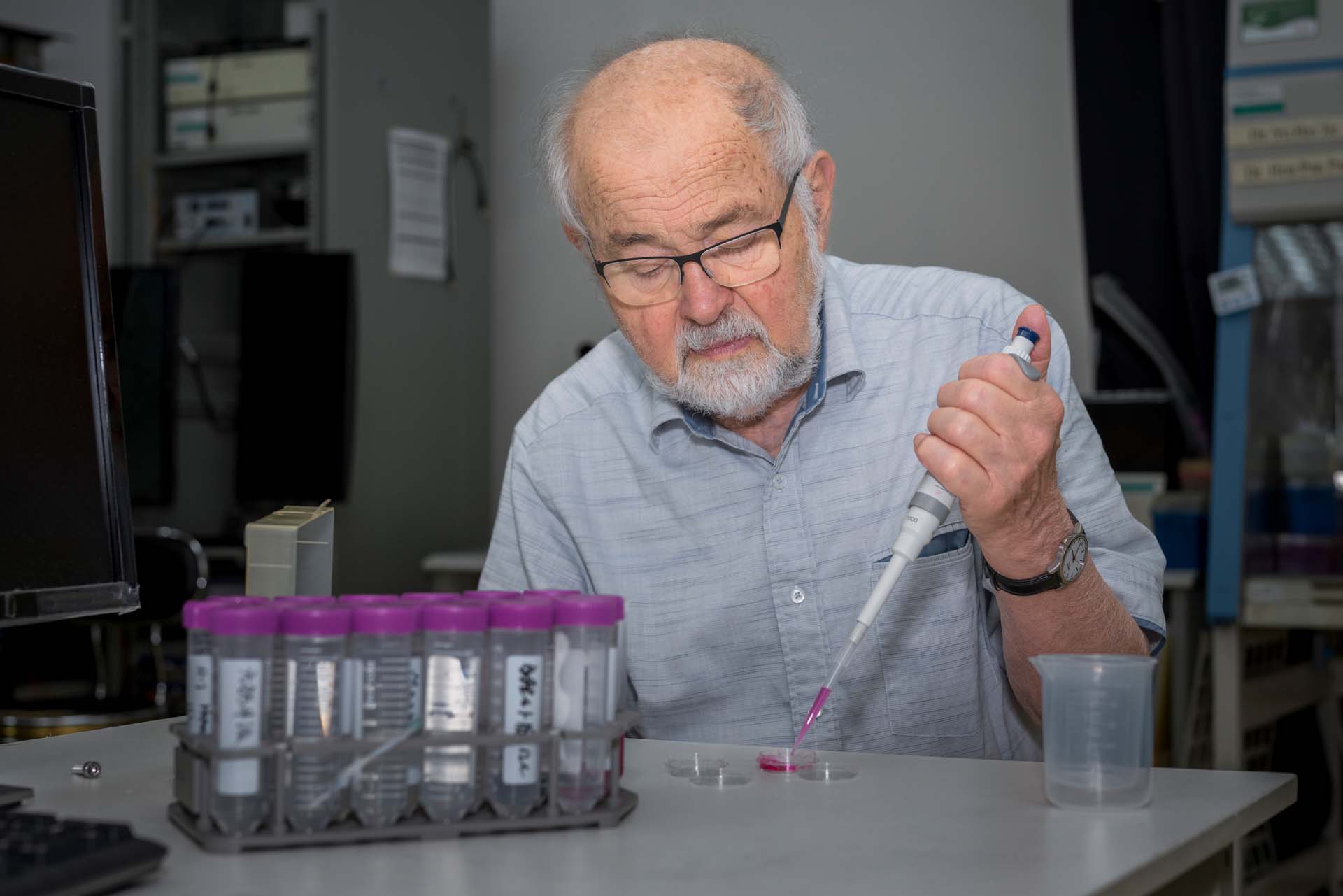

It is almost 10 years since Dr Neher’s Biophysics Laboratory for Innovative Drug Discovery was established at MUST. What results have been achieved so far?

There has been progress on many fronts. There has been important research on a particular ion channel important for the functioning of the heart. There was a formulation developed with a well-defined component from ginseng to serve several purposes. There has also been a product related to goji berries, which are a traditional means in TCM to improve fertility in women at a more advanced stage in life. And there have been many new leads for further pharmacological development.

Have these results surpassed your initial expectations when you accepted this role?

No. I’m convinced that there are probably hundreds, if not thousands, of substances that still need to be discovered, described, and characterised in terms of their action on different cells of the body. I think the output of the laboratory has been very good. My own perception of the field has broadened, and I have realised that there are many, many more things to do. But I think we have reached a good point so far.

You were already a Nobel laureate and highly regarded among your peers. Still, you embraced a new area, where not much work had been done – almost like a pioneer.

I realised that these TCM formulations are a kind of treasure trove of substances important for drug development. In a way, the attitude needed to open up this trove was rather challenging.

In Macao – and in the wider Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area – there has been an emphasis on technology, science, and innovation. In that regard, you are also involved in the Shenzhen Neher Neural Plasticity Laboratory. How do you view the scientific and technological work being done in this part of the world?

Both in Macao and in Shenzhen, research is being carried out at the highest possible level. There is lots of international interaction. The research being conducted is at the top level. And this is one of the reasons why I was attracted to come here.

Your contributions were recognised at the national level in 2024, as you became the first foreign expert linked to either Macao or Hong Kong to be awarded the Chinese Government Friendship Award. What does this award mean to you?

That’s, of course, a great distinction, and I’m very grateful to receive it. But I think the credit doesn’t go to me, but to my early students. Already in 1994, a Chinese student came to my lab [in Germany] to do a PhD. I had several other Chinese researchers join me in the lab, and some of them returned to China. They introduced the techniques that we developed in Germany and enabled a large number of researchers here to do measurements of physiological properties – measurements important for understanding diseases. So, it was my students who introduced the techniques here, and I’m now getting the fruits of that. I want to emphasise that it is an accomplishment of my students.

Science and technology are nowadays advancing at extraordinary speed, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI). What challenges or questions keep a mind like yours engaged?

First of all, there are challenges linked to new technology and the patch-clamp technique [which led to Dr Neher’s Nobel distinction]. It was a method developed in the 1980s and 1990s, when it was very novel and something of a breakthrough. Meanwhile, other methods have been developed, mostly involving imaging technology and molecular biology technology. So, there is competition [laugh], method wise. But there are still areas, particularly in clinical applications, where the patch-clamp technique and electrophysiological characterisation remain the gold standard.

You ask me what I am interested in – in many things. I’m interested in finding new substances from TCM. I’m interested in the mechanisms of synaptic plasticity in the brain, which is a topic of my laboratory in Göttingen [in Germany], and also of the laboratory in Shenzhen. I’m interested in the development from simple neuronal circuits and networks to AI applications nowadays. I don’t work in AI myself, but I’m very interested in seeing how things develop.

I’m more broadly interested in bioinformatics, in the huge amounts of data available from analysis of genomes and different ‘omics’ [scientific fields that study large-scale biological data sets to understand how biological systems function], which require a mathematical background to analyse. But I’m also interested in other areas, like climate change and solving the energy problem, fields where I’m an observer. I’m interested in all these things, and I think this is typically what a scientist is supposed to do.

You have spoken about the importance of basic science research. Why is it so crucial?

I’m very outspoken on that. In many parts of the world, politicians and the public expect immediate results, immediate applications [from scientific research], and urge scientists to focus on applied work. But I think it is important to maintain a balance between different aspects. I see a kind of division of labour: the universities’ job is to teach and to create new knowledge through research; there are research institutes which just concentrate on generating new knowledge; and industry should take that new knowledge and translate it into inventions, drugs, and so on.

It is much easier to derive breakthrough innovations from new knowledge than try to innovate using only existing textbook knowledge, because textbook knowledge has been scrutinised by many competitors for applications. Discovering a new application from it is very difficult. If you are closely connected to a lab that creates new knowledge, or if you are engaged yourself in creating new knowledge, you have a much better chance of achieving real, important innovation.

That begins with engaging children in science. How can their interest be nurtured?

The most important thing is to cultivate curiosity. Young kids are certainly curious to discover everything – to turn every knob in the house, even when they are not supposed to. This curiosity needs to be preserved, needs to be cultivated through appropriate activities where kids can find out what they are good at and whether they really can be patient enough to solve a problem. If, later as students, they find that they have curiosity and the ability to become absorbed in a problem, then they should consider becoming scientists.

What about university students in science and technology fields? This is an increasingly crowded space in which to build a successful career as a researcher.

They should try to find out what genuinely interests them. Of course, they should seek advice, but they shouldn’t just do what others tell them. They should find for themselves what they’re passionate about. Once they have a clear mind on that, they should look for the best laboratory where the particular problem on their mind can be addressed.

What is the weight of a Nobel Prize?

The name Erwin Neher made global headlines in 1991, when the German biophysicist was awarded, alongside fellow German Bert Sakmann, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their research into basic cell function and for developing the patch-clamp technique. It is a laboratory method that detects the very small electrical currents produced by ions passing through the cell membrane. Malfunctioning ion channels are linked to many diseases – from diabetes to Alzheimer’s disease – and patch-clamping helps scientists understand these mechanisms and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Dr Neher was 47 and a father of five with German biochemist Eva-Maria, whom he had met years earlier at Yale University in the United States, when he received the Nobel call. Even now, he admits it is “not easy to answer” how the award went on to shape his career.

“There is definitely a kind of disturbance when you get that call: you can be sure that for the next year or so, you won’t make much progress in your research,” he said. “And it is partly unbelievable what some people think a Nobel is good for [laugh].”

He acknowledges that the title ‘Nobel laureate’ is a powerful calling card. “It opens doors, yes. For collaborations. It makes it a little easier to acquire funding for research.” But it also raises expectations: “You often hear from referees who look at your research papers, ‘I would have expected something better from the lab’ [laugh]. You have to learn how to deal with it.”

A regular visitor to Macao to fulfil his duties at MUST, Dr Neher enjoys the city. “I like to be here, particularly in this area of Cotai, which comes up with new surprises every time I visit.”