A delicate balancing act is needed when it comes to the ecotourism industry in Guinea-Bissau’s Bijagós archipelago. What lies in store for this idyllic island biosphere reserve?

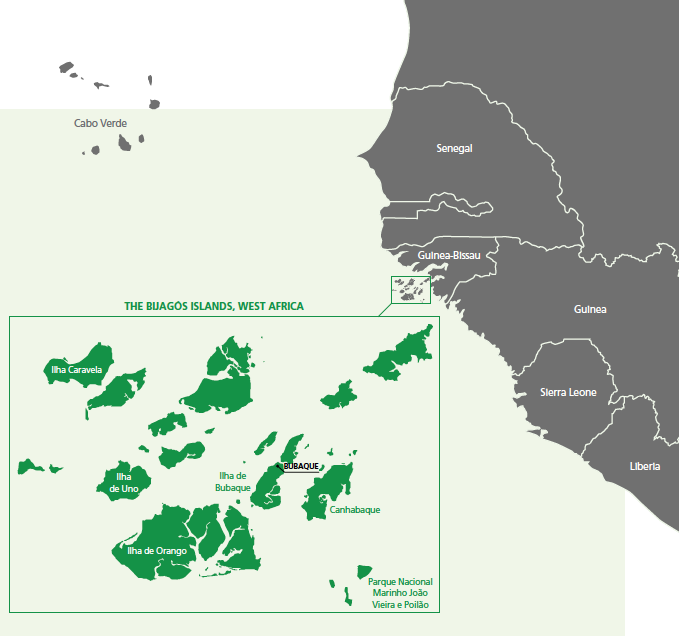

More than 8,000 miles away from Macao, sitting pretty on the west coast of Africa, is the nation of Guinea-Bissau. This Portuguese-speaking country, which is home to more than 1.8 million people, is, as the World Bank last year put it, ‘one of the world’s poorest and most fragile’ nations due to being ‘coup-prone’ and ‘politically unstable’. At the same time, though, Guinea-Bissau, which gained independence from Portugal in 1974, is a land of great beauty. And there’s nothing more beautiful than the Bijagós archipelago, a sparsely populated biosphere reserve that lies just off the country’s coast.

The forested Bijagós archipelago, which is home to 88 mangrove and palm-fringed islands, is referred to as the ‘bemba di vida’ – the ‘barn of life’ – by the 30,000 or so locals in their native Creole language. These locals are animists – people who believe that all natural things, from plants and animals to rocks and thunder, have spirits and can influence human events – and they reckon that anyone who harms these islands will face the wrath of their gods. That includes anyone who harms the habitat of the rare saltwater hippo, an animal that can be spotted around the main island, Bubaque, which forms part of the Orango Islands National Park. This hippo is considered a deity.

Over the millennia, the ethnic Bijagó tribes have shown great respect for their natural surroundings. This, along with the fact that their islands exist in relative isolation from the mainland, has contributed to the preservation of the spectacular concentration of wildlife here, which includes the worshipped hippos, as well as crocodiles, manatees and turtles. Today, however, there is a challenge to this archipelago as the development of the islands for the purposes of tourism looms on the horizon. The country has seen what new developments have done to other tropical paradises across the world and its leaders want to make sure the fragile man-nature balance is kept here. There’s a call for eco-businesses that create wealth and jobs locally – but these have to be planned and carried out with care so that Bijagós does not become a paradise lost.

Biosphere of influence

Next year marks a quarter of a century since UNESCO declared the Bijagós archipelago as being one of the world’s biosphere reserves. That status was given to the islands in 1996 and now they make up one of 701 biosphere reserves in 124 countries across the globe. A biosphere reserve is defined by UNESCO as a ‘learning area for sustainable development’ and thus it is regularly monitored for preservation purposes. It is a site for ‘testing interdisciplinary approaches to understanding and managing changes and interactions between social and ecological systems, including conflict prevention and management of biodiversity’ and ‘each site promotes solutions reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use’.

One of the main reasons the archipelago received biosphere reserve status was the fact that the fauna in its mangroves and on its mudflats is so diverse. According to UNESCO, the archipelago has been recognised as the most important site in Africa for green turtles to lay their eggs, with nearly 10,000 adult females visiting its shores every year. Many other species of turtle also reproduce in the mangroves and other frequent visitors include the rare migratory birds that nest on its shores. The timneh grey parrot is an endangered species. Then there are the locals themselves who need the islands to be as natural as possible as they work in agriculture, forestry, animal herding, fishing and ecotourism. In a report published in May – ‘Natural World Heritage in Africa: Progress and Prospects’ – the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the islands as a future world heritage site. Guided by the World Heritage Convention adopted in 1972, these sites are considered remarkable landmarks or areas with cultural, historical or scientific significance, protected by international treaties and designated as such by UNESCO.

Miguel de Barros, one of Guinea-Bissau’s most renowned sociologists and environmental activists, has been fighting to preserve the islands. He tells Macao Magazine that the local ethnic groups have served as ‘protectors’ of the flora and fauna on the archipelago for many years as they have ‘a culture of low use of the natural resources’ and ‘value the biodiversity’. “The cultural diversity of the Bijagó people is inseparable from [the islands’] biological diversity,” he says. “And it is based on the knowledge and rules that are directly related to that biodiversity.” Barros, who is a consultant for multiple international organisations in Guinea-Bissau, adds that respect for nature is a strong part of the locals’ cultural expression, seen in their masks, dances and sculptures that often mimic or show native animals.

The archipelago is under state protection but there are threats to the reserve. According to Barros, the challenges faced include illegal and artisanal – small-scale with low technology – fishing, as well as the hunting of wild animals, including endangered species like the turtles and parrots. Then there’s the threat of deforestation for agricultural land and even the growing trend of cashew cultivation. Cashews are the country’s main export crop that are quickly replacing other, more traditional crops because they are hugely profitable for farmers. On top of all this, says Barros, the archipelago is also threatened by the privatisation of islands for tourism and future offshore oil exploration projects. Looming too, adds Barros, is the threat of climate change. It is predicted that there could be a significant sea-level rise in the region over the coming decades. This could cause coastal erosion and increase the vulnerability of the low-lying islands.

Barros also says that the local culture itself is under threat. He says that the traditional ‘openness’ of the community to the outside world, especially by the young Bijagó natives, is leading them to question the tribes’ traditional practices and beliefs. This, for Barros, is ‘disintegrating their ties with biodiversity’. He worries that, in the long run, this will ultimately harm the ‘balance’ on the islands because up to now their culture has been a successful ‘mechanism of management and conservation of biodiversity’.

What seems to have been lost in other parts of the world is alive and well here in the Bijagós.

Earlier this year, Guinea-Bissau’s government adopted a National Ecotourism Strategy and the country’s Institute for Biodiversity and Protected Areas (IBAP) published the Regional Responsible Tourism Master Plan for the Bolama-Bijagós Archipelago Biosphere Reserve. Both of these initiatives have the support of conservation partners and the private sector in the country. The government has drawn up a sustainable development model that includes a special place for ecotourism, which is seen as an important tool for the development of the local economy, as well as a way to preserve both the natural wellbeing of the islands and the local cultural heritage. In the government strategy, tourism minister Fernando Vaz says the government and its partners agree that ecotourism is a good fit for the Bijagós islands, supporting the ‘economic development of communities’ in ‘fragile and intact natural areas’. This concept, he says, answers ‘concerns with the development of local communities’ while ‘valuing’ the key feature of ‘biodiversity heritage’.

So there’s a clear drive to increase and improve tourism around the archipelago but this brings new risks, says Barros. The tourism industry is already the biggest employer on the islands, he says, and he notes that it is mainly run and promoted by foreign investors, primarily from Portugal, Italy and France. He claims that the activities on offer include recreational fishing, animal watching and cultural activities which see visitors mixing with the locals when they indulge in activities like eating their indigenous dishes or watching cultural dances. Barros notes that the islands offer the ‘most authentic experience in the country’ to tourists and he worries that these experiences will ‘easily turn into a for-profit show for visitors’.

Fighting for the future

Adelino da Costa is a fighter – both literally and metaphorically. Born in Guinea-Bissau and raised in Lisbon, he became Portugal’s national kickboxing champion in 1999. In 2002, he left in search of the American dream and wound up in New York, where he fought his way up to the title of NYC Middleweight Thai Boxing champion. After that, he became a boxing coach at gyms across the city and later a personal trainer until, in 2006, he opened Punch Fitness Centre in Manhattan. It went well but, according to Costa, all the while there was a ‘calling’ for him to return to his native and rather more tranquil Guinea-Bissau. At the turn of the decade, he decided he’d had enough of the big city, sold his gyms and returned to Africa. In 2016, Costa committed to his first projects in Guinea-Bissau, opening new Punch gyms – which are free for children – as well as an eco-resort in the Bijagós. The Dakosta Eco Retreat in Bubaque was a hit and became a hotspot for martial arts retreats. Today, the 43-year-old says he couldn’t have been happier with his choice to return to his homeland.

“What seems to have been lost in other parts of the world is alive and well here in the Bijagós,” says Costa, adding that the islands’ local communities ‘still live off what nature gives them’ and also ‘heal at Mother Nature’s hospital’ using ‘plants that have been effective through the ages’. “Our job is to keep things the way they are,” he says, whether that means preserving the traditional ceremonies or protecting the mangroves, which can store up to 10 times more carbon per acre than a typical terrestrial forest. Costa, who runs programmes teaching guests at his resort about the local way of life, says the mangroves ‘suck up carbon emissions and are used by turtles to lay their eggs’.

Employing 72 people, Costa’s resort is about ‘responsible and conscious tourism’ as much as it is about ‘bringing value’ to the islands and their precious habitats. For instance, the resort’s menus only feature locally sourced products like oysters, fish, rice, corn and even peanuts. Costa says this way of sourcing creates a ‘development circle’ where villages – known as ‘tabancas’ in the local Creole – and their inhabitants become actively involved in the process. This then helps both tourism businesses and the locals themselves to work together to further protect the islands, he says. “The Bijagós,” he concludes, “have to be protected not only for Guinea-Bissau but for the whole world.”

Another entrepreneur in Guinea-Bissau’s tourism industry is Portuguese national Jorge Horta. Eight years ago, he launched his Africa Princess cruise ship business and it’s been offering accommodation, dining, fishing and sightseeing experiences onboard ever since. He tells Macao Magazine that caution is always exercised, so the environment is not harmed. This includes measures like keeping groups of guests to a maximum of eight people, using the strong currents where possible to transport the vessels in order to save fuel and generating electricity through a series of solar panels fitted to the upper decks. Plastics are also pretty much banned with the boat crews instead making use of the local ‘glass container chain’. This is where all glass bottles are reused to contain drinks which the locals make, like cashew juice and palm wine.

Special precautions are also taken by Horta and his team when it comes to holidaymakers coming into contact with the local population. He says the locals show the visitors the traditional gastronomy, for instance, but in no way does money change hands. “So as not to encourage begging by the [local] people,” he says, “and to support their livelihoods, we never, ever give money to the ‘tabancas’.” Instead, says Horta, the company pays for improvements to the villages, such as building water wells or giving them tools, books or clothes. Sometimes, before the rice crop is harvested, when stocks are low, the company donates bags of rice. On the island of Canhabaque, where Africa Princess has its operational base, the crew and their visitors are sometimes invited by the locals to attend traditional dances – but he says the locals are never paid to stage these shows. He says that would provide an incentive for the ceremonies to be organised for cash and would thus, over time, make them less authentic, harming the overall culture in the long run. Horta adds that to visit certain islands that are considered sacred by the locals, permission is always requested from the village chiefs.

Last month, the government’s Regional Responsible Tourism Master Plan was finalised and within its pages, ecotourism – as opposed to general mass tourism – was defined as the main leisure activity in the islands. “It’s an incredibly important step,” says Horta. The plan proposes a set of governance measures that include the creation of a national board for ‘responsible tourism’ until 2021, as well as an update to the national tourism legislation. It also identifies financing sources such as fees for tourists and tourism service companies and funds from international environmental NGOs.

Pandemic pressures

In the Bijagós, like everywhere else in the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has put a halt on tourism this year. Africa Princess, for instance, went from not being able to accommodate all its booking requests in the early months of the year to cancelling all reservations after March. Prior to the pandemic, the demand for holidays on the islands had been growing in spite of a lack of official advertising. Airlines that fly to the country like Portugal’s EuroAtlantic Airways promote the archipelago but it still boasts that ‘hidden gem’ feel. Transportation can be an issue, however. While Africa Princess guests board the cruise in Bissau to the archipelago, those who venture out by themselves must spend at least one night in the country’s capital city before travelling on a speedboat to their final island destination.

Eleven years ago, when it was even harder to get to the islands, Nicolau Almeida came up with a bold plan: to hold a music festival in Bubaque. For most people, this would have been unthinkable but Almeida is an energetic, determined and fast-talking cultural entrepreneur. He and a small team made it happen. Today, the Bubaque Festival is at the top of Guinea-Bissau’s cultural calendar. Lovers of African music fly from neighbouring countries, as well as Europe and Asia, for a few days of celebration in a unique, lavish natural setting. Many African musical heavyweights have performed at Bubaque, including Angola’s Don Kikas and Super Mama Djombo, a legendary local ensemble dating back to the 1960s who authored – in Creole – some of Guinea-Bissau’s greatest classics, like ‘Dissan Na M’bera’.

Usually held in April, the festival brings together local Bijagós musicians with bands and artists from across the continent. Attendance has been growing steadily every year and it’s now in the thousands. Almeida says that the initial idea was to ‘help end the isolation’ of the islands. He says that, other than showcasing Bijagós music and culture, the festival has actually helped influence the government to improve transportation and facilities. New hotels have been built in and around Bubaque, creating employment opportunities. The local youths have also been encouraged to ‘show off their creativity and craft’, says Almeida. This year’s edition of the festival took place without an audience, thanks to the pandemic. With only eight musical performers, it was held in a local studio and was broadcast live on Facebook. It was a stark contrast to previous editions when the island’s hotels were sold out. But next year’s edition is already being planned.

Open for business

Guinea-Bissau’s authorities are eager to attract investment into the country’s tourism sector and China is clearly a major target. At the seventh Macao International Travel (Industry) Expo in April last year, the African nation was represented by Raquel Mendonça Taborda, at the time a high ranking government member for tourism and handicrafts. She presented several areas of possible investment in the country – including the Bijagós islands. “Only 20 islands are inhabited,” she told the press, “and we are now trying to attract some investments and boost the tourism sector in Guinea-Bissau.” She added that ‘clearly the Chinese market is one of the largest in the world’ and that the African nation already has ‘some Chinese investments’.

Along with agriculture, fishing and mining, tourism is one of the four pillars of the Guinea-Bissau government’s development strategy, as it outlined as far back as 2014. Malam Camará, the country’s representative on the Forum for Economic and Trade Co-operation Between China and the Portuguese-Speaking Countries – or Forum Macao – recognises there is still a lot of work to do to put the nation’s tourism sector on a par with its unique natural and cultural beauties, like the Bijagós. He says that opportunities may arise for investors in the tourism industry, as well as in infrastructure developments – particularly in relation to the islands’ airport and maritime connections – and in health facilities. Camará highlights that the government is offering investors exemptions of customs duties for three years on all imports concerning investment projects. He also says that tax breaks are given even after businesses are launched and if an investment is worth more than US$80 million (MOP 639 million), the government may even lease land.

The strategy is to combine this tourism development with the sustainable management of the islands, making them a world-class eco-destination. Camará even mentions that the archipelago’s resorts and hotels could run gaming operations in the future. In fact, the idea of a casino-resort on Caravela – the northernmost of the Bijagós islands – was explored in 2007 by Geocapital, an investment company which had late Macao gaming mastermind Stanley Ho as a main shareholder. Nothing came of it in the end and today there are no concrete plans out there for such a project.

The tourism industry in and around the Bijagós islands biosphere reserve will undoubtedly grow and improve over the coming years, however, it will be done sustainably and with the protection of flora, fauna and the local culture at the forefront. “The rich diversity of the islands can make it a great international destination for sustainable tourism,” says Camará, “and the government intends to capitalise on those aspects to make the Bijagós spearhead the country’s tourism development.” If it all goes to plan then this paradise won’t just be for holidaymakers – it’ll remain a heavenly home for the local humans and hippos too.

Paradise found

Quick facts: the Bijagós archipelago

- Where: About 48 kilometres off the coast of Guinea-Bissau.

- How many islands: 88.

- How many ‘main’ islands: 15.

- Total area: 12,958 square kilometres.

- Administrative capital: Bubaque.

- Population: Around 30,000 people.

- Notable animals: Saltwater hippos, monkeys, crocodiles, dolphins, turtles, timneh grey parrots and migratory birds.

- Fish: At least 155 species.

- Turtles: João Vieira e Poilão National Marine Park is home to five of the seven species of sea turtles: the green sea turtle, the olive ridley sea turtle, the hawksbill sea turtle, the loggerhead sea turtle and the leatherback sea turtle. The island of Poilão is considered the most important green turtle nesting site in Africa and one of the most important in the world.

- Medicinal plants and herbs: So far, 45 species have been identified in ‘sacred forests’ on the islands. These are reserved for traditional, cultural and religious events.