Built on historical roots from Macao, the Portuguese community in Hong Kong may have been small over the past 175 years – but it has nevertheless remained vibrant.

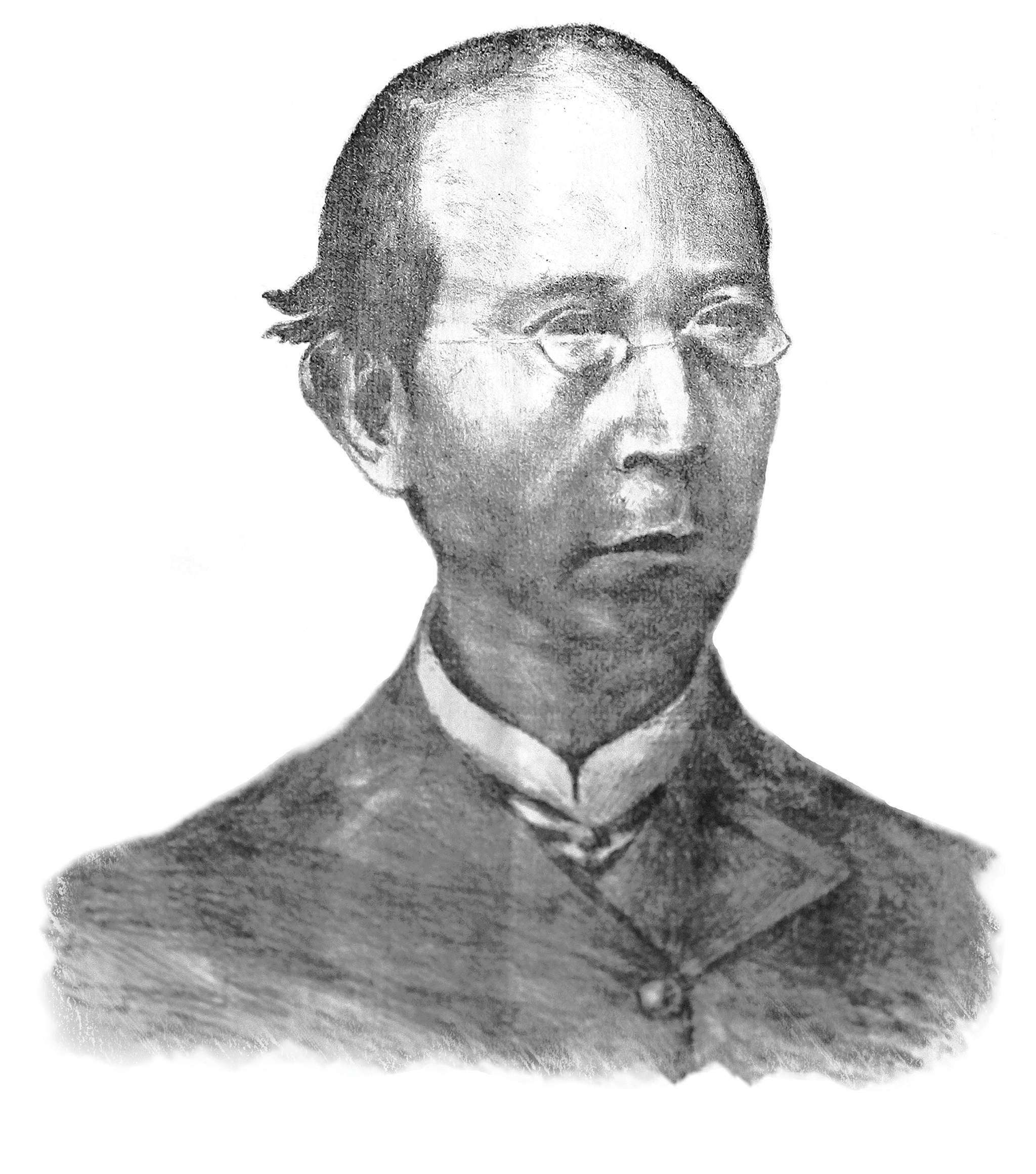

In 1844, Delfino Noronha crossed the sea from Macao to Hong Kong and set up what would soon become the British colony’s leading printing business. The enterprising Portuguese won a contract from the government to print the official ‘Hongkong Government Gazette’, with the high quality of his work attracting an international audience despite local competition from established British printers. He was also involved in the first regular ferry service between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon. Not long after his risky venture across the water, Noronha had blazed a trail in Hong Kong that other Portuguese would follow with determination.

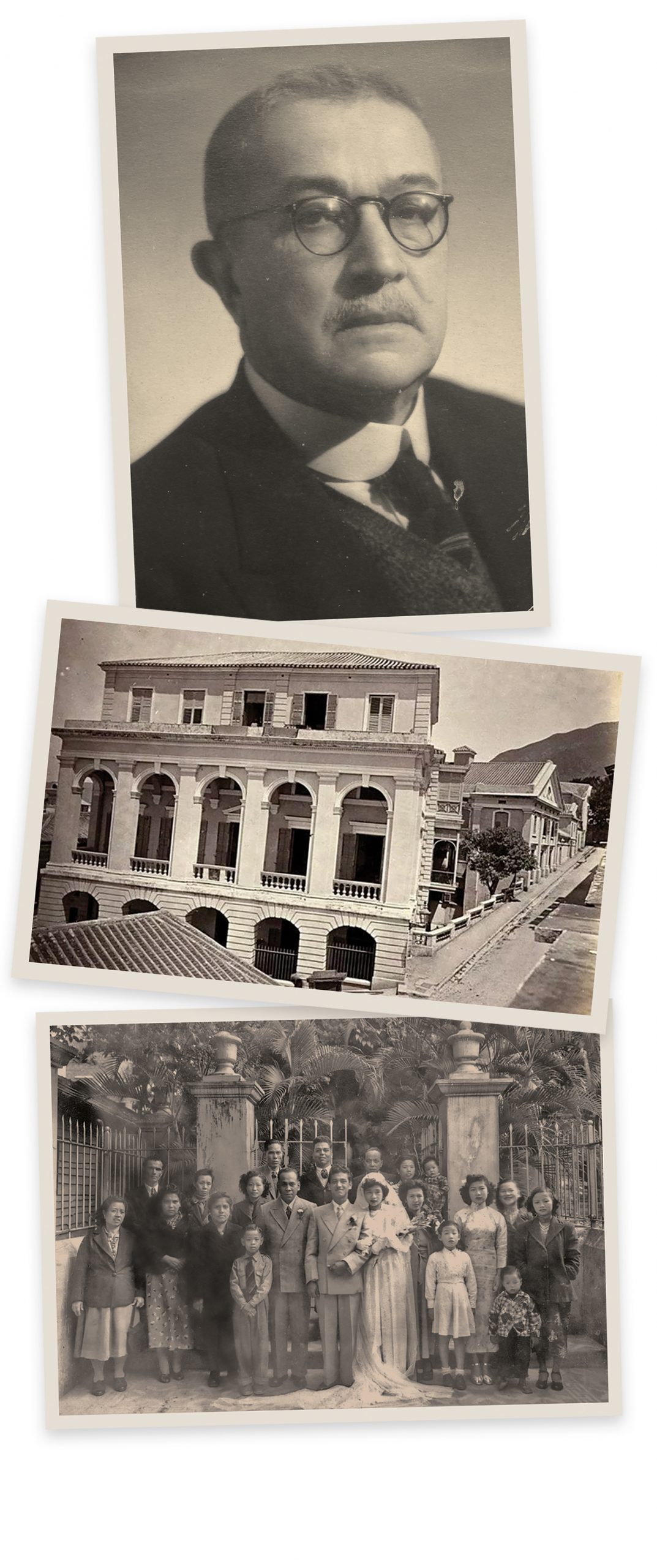

Noronha, as a result, became a leading figure in Hong Kong’s Portuguese community. And many more followed in his footsteps. His grandson José Pedro Braga – who worked for Noronha for a few years and later became manager of the ‘Hong Kong Telegraph’ – was the first Portuguese to serve on Hong Kong’s law-making Legislative Council, between 1929 and 1937. He was also chairman of the China Light and Power Company and, in 1935, was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. A road, Braga Circuit, in Kowloon is named after him.

Noronha and Braga are among a handful of Portuguese who have made enormous contributions to Hong Kong, their adopted city, over the years. The community peaked at around 5,000 people in the early 1960s. Among the most famous community members was Sir Roger Lobo, a member of the cabinet-like Executive Council between 1967 and 1985, and Comendador Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales, the Urban Council’s first chairman between 1973 and 1981. Sales oversaw the construction of many of the sporting facilities that are enjoyed by Hongkongers today.

Stuart Braga, JP Braga’s grandson, is an educator, historian and author who lives in Australia but is well versed on the history of the Portuguese community in Hong Kong. He says the early Portuguese community in Hong Kong was ‘unique’. “Its people had developed their own ethnic identity and their own language they called patuá,” he says, “a creole composed largely of Portuguese and Malaccan influences.”

“They were intensely pious,” he continues, “and remained so for much longer. They had a very strong sense of family ties. Many of them seemed to have been left behind by an advancing world that had suddenly intruded upon their quiet backwater. Some remained caught in a time warp but others would seize very different opportunities that were about to open. They never forgot that they had descended from a nation that had once dominated two oceans, the coast of Asia and achieved great things.”

Despite these achievements many years ago, however, the Portuguese community has significantly shrunk. There are only several hundred Portuguese descendants from Macao left in the city, thanks to mass migration, deaths and assimilation into the local population.

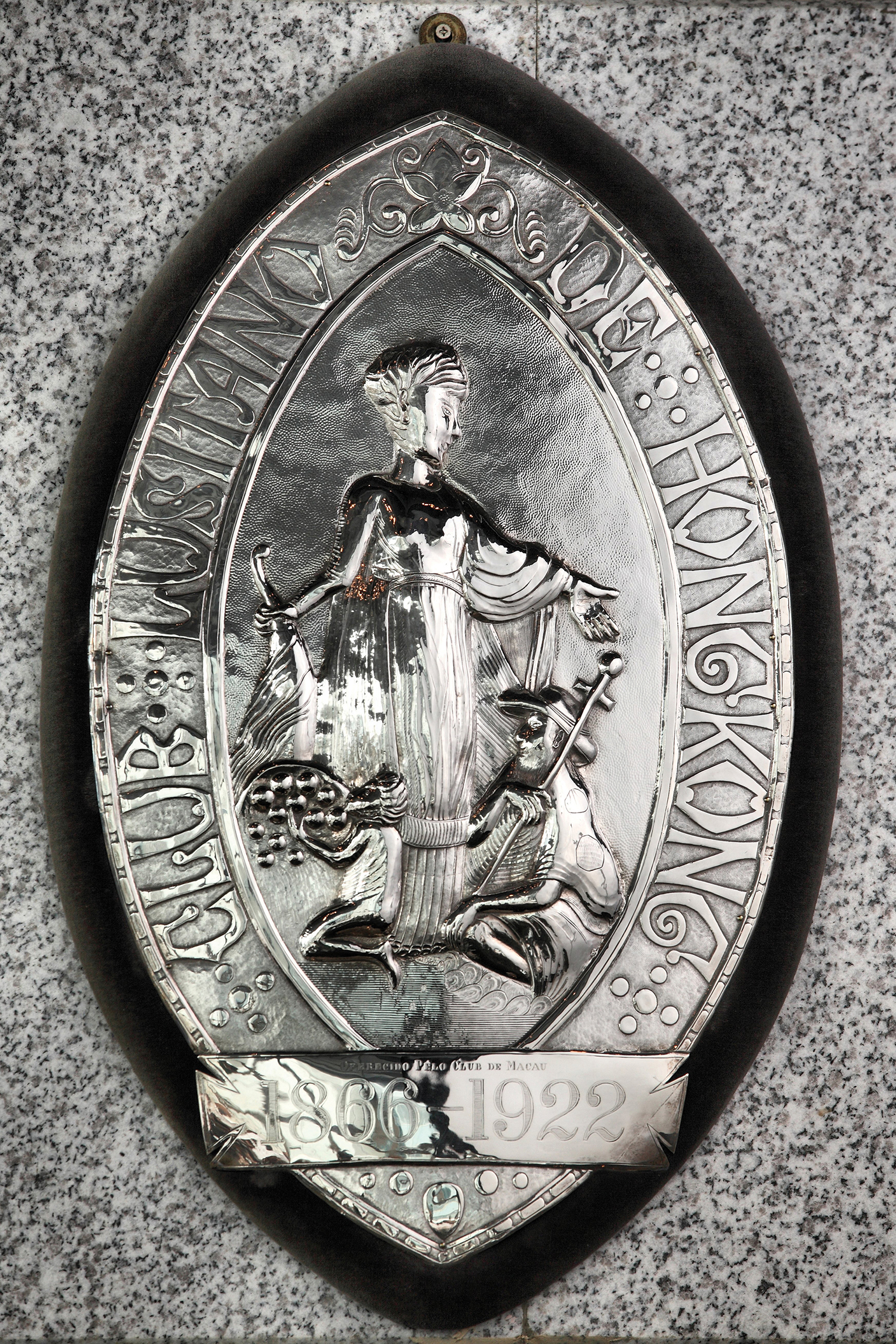

Club Lusitano, founded by JA Barretto and Delfino Noronha in December 1866 and currently located in Hong Kong’s Ice House Street, is symbolic of the community, where traditions are carried on. It has more than 300 members, many of whom live overseas. And outside the club, the Portuguese link is alive, with recent arrivals and descendants working in all sectors, including finance, restaurants, wine and trading.

For example, Team Portugal, a new community group that was set up by Portuguese residents in Hong Kong, participated in a tennis competition in Discovery Bay in March and performed folk dancing at the prize presentation dinner. There are also more Portuguese restaurants, including Casa Lisboa in Central, showcasing the European country’s traditional cuisine. And a reunion of the community is set to take place in November in Macao – the 2019 Encontro.

The Hong Kong Museum of History is revamping its permanent feature exhibit – the Hong Kong Story – and it will be including the histories of the city’s foreign communities. The Portuguese, being the largest at one time, has been invited to proceed first. The exhibition is scheduled to be launched in 2022.

“We are part of Hong Kong,” says Francisco Da Roza, the principal project coordinator of the Portuguese exhibition. “We came with the British on the founding of the new colony. The potential of the city attracted different peoples who came to work, to settle and to make contributions. This is the foundation that made Hong Kong the international city it is today.” Da Roza says that ‘a case in point’ is his great-great-grandfather, Simão Vicente, who emigrated from Macao and settled in Hong Kong. He was recorded as working in a printing firm in Pottinger Street in 1846.

“Three generations of my forebears worked and lived in Shanghai,” continues Da Roza, “starting with my great grandfather, who was the first to have gone to the city from Hong Kong – and I grew up in Macao and Hong Kong. That’s why I assimilate easily with the Portuguese descendants of these three cities.”

Da Roza’s diverse cultural background places him in a good position to pursue this museum project he describes as ‘a fantastic opportunity to revive the collective memory of the Hong Kong community at large’. For his research, he has visited the Portuguese communities in North America. His next destination is Portugal. He speaks with excitement about the many incredible documents, photos and other items he has helped to curate from overseas and local contributors.

New Portuguese arrivals

In the last two decades, the community has been refreshed by new arrivals, attracted by job opportunities in many fields. One is Mark Valadao, a 47-year-old Luso-American who arrived in Hong Kong in 2004 to work in the finance industry. Now he is managing director at private equity firm Skymont Capital, with a family in the city too.

There does not seem to be concrete data as to how many Portuguese live in Hong Kong today but Valadao estimates around 1,000. “We have Club Lusitano, Casa Lisboa and other restaurants, and social media groups,” he says. “In Discovery Bay, for the past 25 years, there has been a Nation’s Tennis Cup. Each team has eight men and four women, all from the same country. This year we formed the very first Team Portugal.

“We Portuguese have a strong sense of identity. We speak Portuguese together. The Portuguese are a migrant people – they have been successful, through adapting and assimilating, as well as keeping their own identity and culture. The Portuguese who were not born and raised here or in Macao see themselves as expats.”

Gonçalo Frey-Ramos, 39, came to Hong Kong in 2006. He is the Asia regional manager for J Portugal Ramos Wines, as well as Ramirez, the world’s oldest packer of canned seafood still in operation. He is married with three children. “Since 2009,” he says, “at the request of the then general consul (Manuel Cansado de Carvalho), I started to organise social events for the Portuguese in Hong Kong. The first was a junk boat trip, then visits to the Club de Recreio and Club Lusitano, lunches, dinners and, of course, trying to get everyone together to watch Portugal games in the European Football Championships and World Cups.

“Since then,” he continues, “we also have a Facebook page ‘Portuguese in Hong Kong’ and, more recently, we organise ‘Portuguese Thursdays’, a casual get-together after work. On special days like 10 June – Portuguese National Day – or Christmas, we try to bring more people together. Everyone speaks Portuguese. They work in banking, architecture, trading, engineering, wine or run their own companies. As other nationals, we have a strong identity, so it feels good to get together.

“The Portuguese have a long history in Hong Kong,” he concludes, “and are connected with many of the local landmarks – the Catholic cathedral for example. There are roads named after the Portuguese. But most are unfamiliar with that legacy. I believe the majority of us never thought to move here permanently.”

Sofia Healey, captain of Team Portugal, moved to Hong Kong in 2012 with her British husband. They have two daughters and live in Discovery Bay. “This year, we set up Team Portugal to play in an international tennis tournament that has been played here for 25 years,” she says. “We won a trophy for the most sportsmanlike and friendly team.”

Like Valadao, Healey estimates about 1,000 Portuguese in Hong Kong, including those from Portugal and those who are second-generation ‘after their parents emigrated to another country’. She adds: “They have come here because of job opportunities or with their spouses. We are not connected with the historic Portuguese community of Hong Kong.

“I have lived away from Portugal since 2000,” she continues, “and feel more of a global citizen. I am married to a British man and my two daughters, nine and five, go to international schools. At home, we mostly speak English. Each summer, we spend six to seven weeks in Portugal, when I speak to my daughters only in Portuguese. The eldest can speak Portuguese now.”

Alongside the British

The Portuguese began to arrive in Hong Kong after the British founded the colony in 1841. They found jobs in business and in the government – and some, like Noronha, went into business on their own. Others worked in the colonial government administration as interpreters or office workers and some joined commercial banks and big trading companies. They were fluent in English and Chinese, acting as middlemen between the British and the locals.

More Portuguese began to arrive in Hong Kong from Macao at an accelerated rate after the city’s Governor João Maria Ferreira do Amaral was assassinated by seven Chinese men in August 1849 – and also in 1874, after Macao was hit by a major typhoon in September that caused great devastation.

Club Lusitano was founded in December 1866 as a centre for Portuguese social life. A second, Club de Recreio, was founded in Kowloon in 1905. The new migrants quickly learned to speak English and found jobs in government and business. “Aside from the British,” says Da Roza, president of Club Lusitano between 2009 and 2012, “our community was more distinct than the other foreign communities. We had our churches, our schools and social and sports clubs. We were a closely knitted community with our own culture and dialect, all brought from Macao. There is the background of the historical link between Portugal and Great Britain. So, for example, both British and Portuguese official dignitaries attended the opening of the Club Lusitano.”

End of the golden age

After the 1967 riots in Hong Kong and Macao, many Portuguese emigrated to Canada, Australia, Portugal, Brazil and the US. After the war, most of Da Roza’s family moved to Venezuela. He, however, has been in Hong Kong for more than 50 years after spending a part of his childhood in Macao. His first ancestor came from Portugal to Macao more than 300 years ago.

Most of those who remained have assimilated into the primarily Cantonese-speaking community. Da Roza married a Hongkonger and their children have Portuguese names. They went to international schools and attended overseas universities – and often they speak more English and Cantonese than Portuguese. Without Portuguese being spoken at home, it is hard for children to learn the language. In Club Lusitano, the main language spoken is English, followed by Cantonese.

Many people of Portuguese descent have made their mark in the Hong Kong scene, such as Cantopop star Isabella Leong, whose birth name was Luísa Isabella Nolasco da Silva. There is also Miss Hong Kong 1988 Michelle Reis, singer and show hostess Maria Cordero and Radio Television Hong Kong DJ Ray Cordeiro, 94, known professionally as Uncle Ray. In 2000, he was named ‘The World’s Most Durable DJ’ by the Guinness Book of World Records. There is also well-known racehorse owner Archie da Silva, famous for the exploits of his champion runner Silent Witness, the world’s top sprinter for three seasons. They and others of the Portuguese community are proudly accepted as being locals – with each of them continuing to contribute to Hong Kong.

In 2003, Club Lusitano expanded its membership with the admission of women members and in 2016, it celebrated its 150th anniversary with a week-long celebration of Portuguese cuisine and a black-tie gala ball. It now has more than 300 members and is undergoing a renovation which, when complete, will see it re-open in September. Club Lusitano’s treasurer Anthony Correa says: “Club Lusitano has been the exclusive preserve of Hong Kong’s Portuguese community since 1866. The renovation will provide members with upgraded facilities and expanded services that will allow the club to significantly expand its current resident membership. Adult Portuguese citizens and persons of Portuguese extraction are welcome to apply.”

Like the original Portuguese community that began to thrive in Hong Kong over 150 years ago, the ambitions of Club Lusitano prove that this community may be comparatively small but it will always be vibrant.

Hong Kong Portuguese Community Artefact Collection Campaign

Ahead of the exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of History, the museum has launched a campaign for documents, objects, photographs and other items of historical interest in connection with the community. If you have any relevant item you could lend or donate, call +852 2763 7367 or email portuguese@lcsd.gov.hk.