One hundred and fifty years ago, in 1873, the governor of Portuguese-administered Macao, Januário Correia de Almeida, became Portugal’s first envoy to meet Emperor Mutsuhito – the first monarch to effectively rule Japan since the 1330s. Januário Correia de Almeida stopped by Nagasaki on his way to the Empire of the Rising Sun’s brand new capital, Edo (now Tokyo).

At that time, Japan was still emerging from Sakoku (1639-1853), a period of more than two hundred years where the country barely interacted with the rest of the world. But Portugal and Japan’s relationship dated back almost a century before Sakoku began. In fact, it was Portuguese merchants and missionaries who transformed Nagasaki from a fishing village to a centre for trade in the late 1500s – around the same time as the growing maritime power was establishing itself in Macao.

In 1543, three Portuguese adventurers were the first Europeans to set foot in Japan. A typhoon drove them into the Ryukyu Archipelago and, in a chance encounter that ended up shaping the future of Japan, their Chinese junk got shipwrecked on one of its islands, Tanegashima.

Those Portuguese interlopers introduced locals to matchlock-style firearms, an early form of musket that used a length of burning rope to ignite the gunpowder within. The island happened to be home to skilled swordsmiths who were able to quickly reproduce the gun; their version of it became known as ‘tanegashima’ and was adopted by the Japanese samurai. Ultimately, the weapon allowed the feudal lord and military leader Oda Nobunaga to reunify what was then a torn-apart country.

Japan’s reunification took place during the so-called Nanban period of trade, another direct result of the 1543 shipwreck. Portuguese traders went on to ply a route connecting isolated Japan with southern China (Nanban, incidentally, means ‘southern barbarian’). They’d buy Chinese silk at the fairs of Canton to sell in Japan, where they stocked up on gold, silver and copper for their return voyage to China. Just a few years into this highly profitable era of mercantilism, Portugal claimed conveniently located Macao as its base for trade with the Far East.

Nobunaga, by then Japan’s effective ruler, encouraged free trade and offered protection to the Portuguese merchants sailing in from Macao. And where European traders go, Christian missionaries follow. Japan was no exception. Francis Xavier, one of the founders of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) reached Japan in 1549 as an Apostolic Nuncio and it was in that capacity that he presented himself to the daimyo of Yamaguchi. Jesuits brought with them Catholicism, but also the latest scientific advances and culture from Europe. From European fashions and food to Western medical knowledge and architectural techniques, the Japanese absorbed it all. The missionaries founded Japan’s first ‘modern’ hospital, orphanage and Western-style art school. They also published the first Japanese dictionary and grammar books.

While Nobunaga led Japan, merchants and missionaries enjoyed full support from Japan’s authorities. But this gradually decreased under the rule of Nobunaga’s successors, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and then Tokugawa Ieyasu. The spread of Catholicism, courtesy of the Jesuits, concerned them – these leaders suspected religious conversions were a covert way for Europeans to take over the country.

Toyotomi eventually ordered 26 Japanese converts to be arrested and crucified in Nagasaki as a warning to their compatriots. The executed Japanese Catholics are now known as the 26 martyrs of Japan. Under Tokugawa’s rule, Catholics continued to face repression, persecution, and often death. The Tokugawa shogunate progressively closed Japan off to the outside world and by 1639, the Nanban period had well and truly been replaced by Sakoku. Trade and diplomatic relations were severely curtailed; virtually all foreigners were barred from entering the country, and the Japanese public weren’t allowed to leave.

Japan’s return to isolation was the start of a long and relatively peaceful chapter of the country’s history. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled between 1603 and 1868 (this time is also known as the Edo period) and oversaw a ‘Japanese Renaissance’. Traditional arts and cultural practices such as ikebana (flower arranging) and chanoyu (tea ceremonies) were refined, while numerous new forms of art were developed – including porcelain, haiku (poetry), kabuki (musical theatre), ukiyo-é (prints) and ukiyo-zuchi (popular fiction). The Japanese used techniques and skills learned from the Portuguese to fine-tune these practices and products. In fact, historians argue that there’d be no Japanese renaissance without that earlier Portuguese influence.

The Edo period was also marked by famines, natural disasters and peasant unrest. And in its later years, increasing Western intrusions highlighted the technological divide between Japan and the West, where the Industrial Revolution was well under way.

Japan’s return to the world

In the 1850s, the US was a newly minted Western power on the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean. Its representatives forced Japan out of Sakoku, with the Treaty of Peace and Amity (1854) and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (1858). The new treaties piqued the interest of Portugal’s then king, Pedro V, who instructed the governor of Macao, Isidoro Francisco Guimarães, to hurry to the Japanese capital and negotiate a trade deal benefitting Portugal.

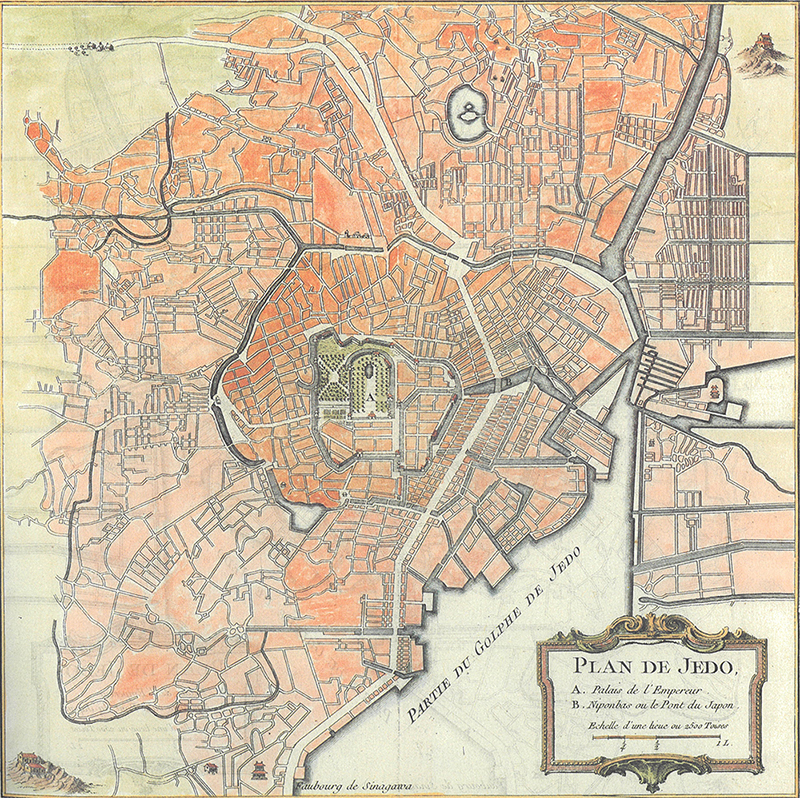

But political turmoil in Japan, coupled with complicated home affairs in Macao (Portugal was in the midst of wresting control over Taipa and Coloane Islands) meant that Guimarães’ mission didn’t leave Macao until 1860. He and his fellow diplomats arrived in Edo that July, aboard the corvette D João I and under the command of Feliciano António Marques Pereira. On 19 July, the Portuguese plenipotentiaries secured an audience with the Governor of Edo and representatives of the ruling shogun. At the Government Palace, they made their presentation in Portuguese, which was translated first into Dutch (Japan’s language of commerce with the Americans and Europeans), then into Japanese by interpreters. Tea, sweets and cigars were served at the end of the ceremony.

A few weeks later, on 3 August, the two countries signed the Treaty of Peace, Amity and Commerce. Guimarães signed on behalf of Portugal’s king, while Midzogoetsi Sanoekino Kami, Sakai Okino Kami and Matsdaira Dzirobe signed on behalf of the Japanese shogun. To celebrate, the Portuguese hoisted the Japanese flag on their ship and fired off a series of salvoes. A day later, they delivered a letter from the king to the shogun; this was reciprocated by a special Japanese meal delivered in lacquer boxes. Before leaving Japan, Guimarães appointed Macao-born José da Silva Loureiro to serve as the Portuguese consul in Kanagawa (part of Edo).

Once the treaty had been ratified, many Portuguese families from Macao moved to Japan to establish the likes of banks, insurance companies and trading companies. This period of Portuguese expansion overlapped with the 1868 Meiji Revolution, which restored power to the Emperor of Japan. The Meiji Revolution spelled the end of the isolationist Tokugawa shogunate and the start of Japan’s rapid modernisation and industrialisation – helped along by the Europeans now allowed to live and work there. It was into this climate of change that Isidoro Francisco Guimarães’ successor, Januário Correia de Almeida, entered Japan in 1873.

Another century of Portuguese influence in Japan

The subsequent wave of Portuguese reaching Japan from Macao, Hong Kong and Shanghai mainly settled in Yokohama and Kobe. There, they founded Portuguese clubs and schools and were considered to be one of the more influential foreign communities in Japan. The Macao-born accountant Vicente Emílio Braga, for instance, introduced Japan to double-entry bookkeeping. In the 1870s, he was transferred from his role as chief accountant at the Imperial Mint in Osaka to teach accountancy at Japan’s Ministry of Finances.

Up until the 1920s, Portugal’s main exports to Japan were wine and cork, the latter used in naval construction. Portuguese diplomats promoting trade and relations with Japan at that time included José da Silva Loureiro, Eduardo Pereira, Venceslau de Moraes – who later became consul in Kobe and a prominent writer on Japanese culture – and Batalha de Freitas.

During the earlier Nanban period, the Portuguese language had been widely used across Japan. But the first Japanese education provider to introduce Portuguese in its curriculum was the Tokyo Commercial High School (now the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies), when Professor João Abranches Pinto started teaching the language in 1917.

When Japan sided with Germany and Italy in World War II, Portugal – as a neutral country – maintained its diplomatic relations. While Japan’s Imperial Army occupied Guangzhou and Hong Kong in the 1940s, as well as Portuguese Timor, Macao avoided this fate.

Portugal-Japan ties in the modern era

A turning point for Portugal and Japan relations came in 1964 when Portugal sent 20 athletes to compete in Tokyo’s Summer Olympics. The Portuguese ambassadors Armando Martins and Almeida Coutinho also improved the two countries’ cultural and commercial ties, laying the foundations for several significant developments between the late 1960s and early 1970s. Japanese universities, for example, began offering courses in the Portuguese language.

The Portuguese company Salvador Caetano started importing Toyota vehicles, while the Portuguese shipping company Soponata used Japanese shipyards for its huge oil tankers. At Expo ‘70, the 1970 world fair held in Osaka, the Portuguese pavilion boasted a replica of a monument on the island of Tanegashima (where the first Portuguese to reach Japan were shipwrecked) representing friendship between the nations. Japan was also the first country to buy petrol from then-Portuguese Angola.

The 1970s were also a time of major political, social, and economic upheaval in Portugal. As its anti-colonialist Carnation Revolution overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime in 1974, Portugal’s African territories gained independence – sparking a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens, who became refugees. Macao remained under Portuguese administration until its 1999 handover to China; incidentally, the 1990s also saw the Japanese public become increasingly interested in Portuguese music, art, cinema, and sports. There were many state and private visits between the countries’ respective leaders. As an example, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko went to Portugal on an unofficial visit in 1998.

After 480 years, Portugal will always be Japan’s oldest friend in the West. The fact that Portuguese-administered Macao served as the nexus for the two countries’ ties throughout the centuries, picking up again after the end of Sakoku, makes for a strong connection between the Macao Special Administrative Region and Japan today.