Although coffee is not the only agricultural business of Timor-Leste, it is the leading product that has brought much worldwide exposure and economic gains for the community.

Most international attention on Timor-Leste is directed at the fortunes of the Greater Sunrise hydrocarbon project, but another sector has the ability to affect Timorese lives more directly. Coffee accounts for 90 per cent of the country’s non-oil and gas export revenues and has the potential to play a much bigger role in rural development. Yet with half the yields per unit area of even Papua New Guinea, the sector requires a substantial overhaul.

There is some controversy over whether it was Chinese traders or Portuguese colonists who first brought coffee trees to the country. Either way, by the 1860s coffee accounted for at least half of the territory’s entire export revenues, with only a small number of Portuguese landowners controlling both cultivation and sales.

Like many other parts of the economy, the coffee sector suffered from underinvestment during the 1975–99 Indonesian occupation and the armed resistance. Far too few coffee trees were planted and so farmers became over-reliant on ageing trees. Little investment was made in passing on skills or adopting new techniques, and both coffee quality and productivity declined as a result. Since independence, there has been some replanting as well as some training programmes being held; however, much more is needed.

Existing trees could benefit from pruning but this would make them unproductive for at least two years, which would represent a big financial sacrifice for concerned farmers. In addition, the country is not ideal for coffee cultivation due to the short rainy season, prolonged dry periods, and low soil fertility rates; beans are still often sorted by hand.

Coffee accounts for 90 per cent of the country’s non-oil and gas export revenues and has the potential to play a much bigger role in rural development.

The World Bank calculates yields at just 150–200 kilos of green beans per hectare, one of the lowest rates in the world. Part of the problem in supporting the sector is the lack of reliable data. Estimates of the number of coffee farms vary from about 46,000 up to 67,000. The country exports about 100,000 60kg sacks of coffee a year, although the figure is slowly rising.

Timor-Leste is the source of the Timor Hybrid, sometimes called Tim Tim, a strain of coffee tree that spontaneously emerged before World War II from Arabica and Robusta strains. Known for producing pest and disease resistant plants, it offers high-quality beans and high yields, and is cultivated around the world. Arabica coffee trees are traditionally sweet but fragile, while Robusta – as the name suggests – has a harsher taste but is more disease resistant. Both Robusta and Arabica coffee are grown in the country.

Some in the industry suggest that Timor-Leste’s hybrid will become more popular as climate change affects existing, less hardy strains around the world. However, in an era of genetic patents, it seems unlikely that the country itself will derive much benefit from its contribution to the world.

Starbucks involvement

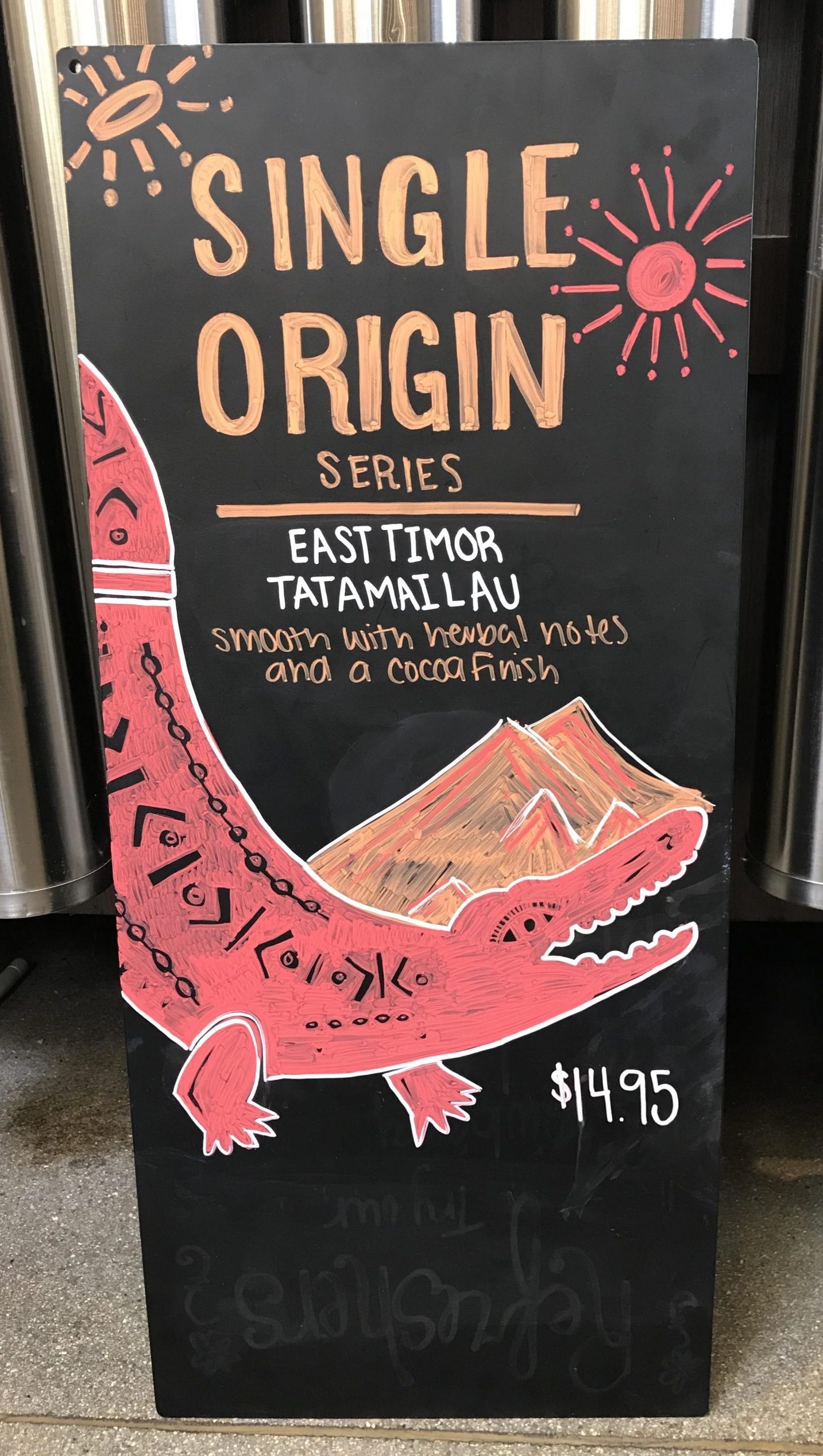

Coffee giant Starbucks has a huge role to play in Timorese coffee. It bought its first coffee from Cooperativa Café Timor in 1996 and has continued to buy since then. The US firm began blending Timorese coffee with South American beans in 2005 to create an organic blend called Arabian Mocha Timor. The company says that the quality of the beans has improved over the past two decades and launched its single origin East Timor Tatamailau coffee in 2017. Mackenzie Karr of the Starbucks Coffee team said the company’s single origin range is “an opportunity to showcase rare and unique coffees that we wouldn’t be able to otherwise.”

The reliance of farmers on any single multinational corporation is often criticised but initial research into Starbucks role in Timor-Leste is positive. Starbucks decision to launch the Tatamailau single origin coffee has certainly helped to promote Timorese coffee around the world, creating much-needed marketing in the process.

A study into Timor-Leste’s agriculture sector by Sweden’s Research Institute of Industrial Economics in 2012 noted: “So far, exports have predominantly targeted high-quality niches in foreign markets. The decision by Starbucks to sell coffee from Timor-Leste has provided a major boost to the reputation of the product and has opened a large potential market.”

In a statement, the company said: “The move by Starbucks to sell ‘single origin’ coffee sourced from Timor-Leste in supermarkets is expected to help alleviate deforestation and contribute to growing the country’s economy.” A study by the United Nations Development Programme in 2013 highlighted the growing problem of deforestation in the country. There is little doubt that the economic development generated by Starbucks’ involvement should boost rural development, particularly as the cooperative that supplies the company includes about 22,000 farmers.

As part of its engagement with farmers in developing countries, Starbucks has worked alongside Conservation International to develop its Coffee And Farmer Equity standards covering the entire production chain to ensure that farmers and processors are paid a fair price and that the coffee is grown in an environmentally sustainable manner. It has also provided fixed and mobile clinics to improve the health of coffee farmers and their families in Timor-Leste.

Rural development

Despite coffee’s position as the dominant export crop, it generates only about US$12 million a year in income, so there is clearly room for expansion in the six municipal districts, out of 13 total, in which it is cultivated. Along with tourism, the sector has been targeted as a great source of job creation, as almost every stage of the process is very labour intensive, from planting and harvesting to drying, processing, and packaging.

With such a dominant single crop, promoting coffee production is one of the best methods of tackling rural poverty, including high child mortality rates and malnutrition. Many farmers are unable to save enough money to last for a full year following the May–October harvest season. The World Bank estimates that a 1 per cent increase in agricultural yields reduces poverty by 0.5 per cent in East and South Asia.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has sought to support the sector’s development, including through the award of a US$225,000 grant from its Technical Assistance Special Fund to finance quality and quantity increases in the coffee produced by smallholder farmers in 2017 and 2018. The ADB is also funding ongoing trials into the cultivation of new varieties of coffee and the production of a comprehensive coffee sector development plan, which is being completed with the support of the private sector. The plan is to focus on the rehabilitation of existing coffee farms.

Coffee industry consultant Andrew Hetzel was appointed by the ADB in 2016 to assess the sector in Timor-Leste. One of the main recommendations of his report was the creation of a new organisation bringing together those working in the sector. According to the ADB, Hetzel “theorised that communication among its disconnected and sometimes adversarial stakeholders could lead to new cooperation, and the creation of a democratic forum promoting advancement of the industry”.

The Timor-Leste Coffee Association, or Assosiasaun Café Timor-Leste (ACTL), was duly set up in 2017, with the support of the ADB, and includes members from all parts of the sector, including farmers, distributors, donor agencies, and government. The association now has its own headquarters and cupping lab in Dili.

The ACTL set up Festival Kafe Timor in November 2016 and the Timor Coffee Festival one year later. Both events were used to promote national pride generally as well as Timorese coffee specifically. The latter event was backed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and attracted coffee experts from other countries, including the US and Australia, as both buyers and speakers at the event. A national coffee quality competition was held and international buyers undertook trips to smallholder communities where farmers were unable to travel to Dili.

David Freedman, the country economist from the ADB’s Timor-Leste Resident Mission, said: “Coffee is grown by almost one-third of all Timorese households and has been the country’s largest non-oil export for the past 150 years. Coffee has the potential to play an important role in the future development of Timor-Leste, providing certain weaknesses in coffee production are addressed.” Starbucks estimates that 46 per cent of households in rural Timor-Leste rely solely on coffee cultivation to generate income.

The future

More trees are being planted and production should increase steadily over the next few years. One of the big questions facing the sector is how intensively to farm coffee. World Bank research suggests that productivity could increase by more than 50 per cent with even basic investment, while using more modern inputs could boost this figure still further. However, one of Timor-Leste’s main selling points is the fact that chemical pesticides and fertilisers have never been used in most areas and it should be possible for farmers to secure organic accreditation.

The sector has benefitted from investment in more general infrastructure, including in the road sector. For instance, the European Union agreed to provide a US$22.62 million grant to finance the rehabilitation of 44 km of road in Ermera and Liquica municipalities. The work, which is scheduled for completion by the end of 2019, is being undertaken by China’s Shanghai Construction Group Company Ltd and is designed to ease the transportation of coffee to markets. Many other roads still need upgrading.

It is vital that the government and the country as a whole do not see coffee as a panacea for all the problems of rural development. At present, the main staple crops are maize and rice but yields are roughly half as high as in neighbouring Indonesia. An ideal combination would be coffee cultivation and higher yielding staple crops.

NGOs are working with farmers to identify the best subsistence crops for the country’s climate, topography, and soils. Farmers already produce cocoa, mango, breadfruit, pepper, cloves and vanilla, while there has been some success in promoting the cultivation of soya beans, which would provide a big boost to agriculture in general because legumes increase soil fertility.