A tea master rhythmically unravels a piece of turquoise fabric on the floor, creating a graceful sea of blue. He gently edges his knees onto a cushion, then arranges a large kettle, delicate teacups, a ladle and a bouquet of pink blossoms across the fabric as if he is painting. The Macao Chinese Orchestra plays classical Chinese music in the background, enhancing the calming and poetic atmosphere.

In 2018, local tea connoisseur Lo Heng Kong demonstrated this unique tea ceremony, which he designed himself, to celebrate the drink’s history in Macao and encourage its appreciation. Instead of making tea at a table, as is tradition, Lo kneels on the floor to be closer to nature. He also aspires to transform tea ceremonies into performance art by using the fabric – which can be any material – as a canvas.

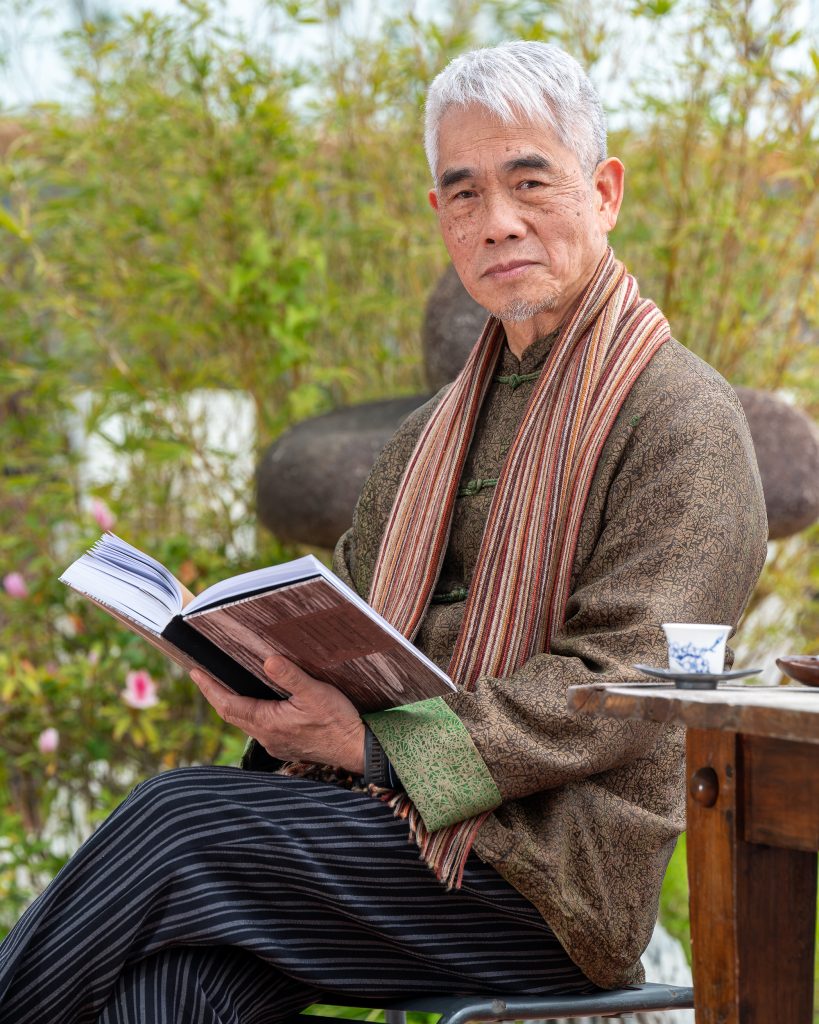

In 2020, the tea master wrote about creating this modern tea ceremony in his book, Tea Ceremony Setting and its Designs, which includes many photographs and setting designs by Lo and the members of his Chinese Teaism Association of Macao. But while writing the book, the 68-year-old discovered that many people worldwide do not know about the city’s tea culture. This realisation inspired him to embark on his new book: My Notes on Tea: The Past and Present of Tea in Macao, published in 2021.

Part memoir, part account of tea’s history in Macao, Lo’s new book feels like an archaeological dig, in which Lo attempts to dust away misconceptions and unveil the truth. “I hope my readers can use the book as a reference and historical record,” says Lo.

“Tea is not only for drinking. Many misunderstand that the art of tea originates from Japan, but it actually passes on from China [to Japan and beyond]. It saddens me to hear this [that Chinese culture is not well understood and respected], so I decided to find the origin and present it here [in the book].”

Macao’s preeminent tea expert

Lo is well-positioned to tackle such a broad topic thanks to 20 years in the tea industry. In 1997, when Lo was in his early 40s, he left a career in interior design and embarked on a lifelong journey devoted to tea – from brewing to ceremonies, history and appreciation.

That same year, Lo opened Chun Yu Fang (meaning ‘Workshop of Spring Rain’), in Taipa. The teashop invited enthusiasts to learn about tea appreciation, enjoy the drinking experience and purchase tea. While running the shop, Lo sold a selection of high-quality tea leaves and shared tea-making experiences with regional experts from the mainland, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea.

In 2000, he founded the Chinese Teaism Association of Macao and delved deeper into teaching and research. “I love tea, as well as teaching the art of tea. Instead of having only a few lessons, I hoped my students could sustain their studies, so I established the association,” he says. “I also came across some issues, such as the inconsistency between tea and the suitable tea-making tools, so I started designing proper tools. I want to provide comprehensive knowledge about the art of tea.”

Seven years later, he moved Chun Yu Fang into the green hinterlands of Coloane, an island of Macao, and changed its name to Chun Yu Fang Tea House. The tea master says his tea house is his dream. “As I buried myself in writing and research, and [would be] getting older, I hoped to find a proper spot for teaching and research.”

His experience and research on tea have led to many academic opportunities. Lo frequently gives lectures and workshops in local secondary schools and higher education establishments, including the Macao Polytechnic Institute’s Seniors Academy. He has also travelled extensively to share his knowledge during seminars in the mainland, Japan and South Korea while consulting for tea associations in the mainland.

For example, Lo is an honorary committee member of the China International Tea Culture Institute, an honorary researcher of Ningbo East Asian Tea Culture Research Centre and a consultant of Hebei Tea Culture Association. In 2009, he was granted the honorary title of merit by the Macao SAR government for his devotion to society.

Tea takes hold

This world of experience prepared Lo to produce his ambitious new book, My Notes on Tea. Designed by Lo’s student, Zen Wong, the cover features an illustration of a broken wooden door with a keyhole in the middle. Peering through the hole, readers can see a tiny porcelain teacup – the same type used at the famed Kun Nam Tea House, which operated from 1953 to 1996 on Rua de Cinco de Outubro.

According to Lo, the delicate teacup (made in Jingdezhen, a famous ceramics manufacturing hub in Jiangxi province) showcases ideal proportions, a lightweight body and finely detailed artwork.

This teacup is symbolic for Lo and overflows with memories. He recalls visiting Kun Nam Tea House with his father, a tea house manager who had a keen sense of tea making and appreciation. “My father had a deep knowledge of tea. He was a busy man. Life was tough back then, so I couldn’t bring myself to ask him questions,” says Lo. “When writing the book, I really regretted not finding out more about tea from him.”

But Lo’s insights prove more than sufficient, with My Notes on Tea providing a deep dive for beginners and connoisseurs alike. Divided into four chapters, the book covers a lot of ground, from tea’s beginnings in China to Lo’s tea memories in Macao, tea ceremonies and tea-making tools. Through a mix of research and storytelling, Lo strives to trace tea’s footsteps through Macao while celebrating the art of tea. He also wants to debunk a pervasive misconception worldwide – that tea originated in Japan, not China.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, among other respected sources, tea originated in China around 2700 BCE and gained popularity in the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties. In the 8th century, Buddhist monks brought tea leaves from China to Japan, where elites began consuming the drink for medicinal purposes. By the 13th century, the Japanese tea ceremony emerged, though it was initially rowdier than today’s formal experience. Around the same time, the drink became available to everyday people to consume for both health and enjoyment.

In Macao, the “golden age” for tea, as Lo calls it, ran from the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s, while the Portuguese settled in the territory and established a trading port. Guangzhou, then known as Canton, was an important Chinese port, which had been open for foreign trade since the 14th century. It was also the only port open to foreign trade from 1757 to 1842. Since Macao was located just 150 kilometres down the Pearl River, the city became an important entrepôt – a trans-shipment port where goods can be reloaded for the onward journey – for Chinese goods.

Though they operated trade routes with Europe, the Portuguese did not ship tea at first. It was the Dutch who introduced Chinese tea to Europe via Japan in the early 1600s. Around the mid-1600s, British merchants also started shipping Chinese tea to England. It was primarily consumed for medicinal purposes until Queen Catarina de Bragança popularised the drink.

As the daughter of Portugal’s King D João IV, Queen Catarina had access to Chinese tea via Macao and drank it daily for enjoyment. When she married England’s King Charles II in 1662, she is thought to have made tea more fashionable as a social beverage.

After the turbulent transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties in 1683, the Kangxi Emperor banned foreign trade unless it went through Macao, which gave the Portuguese an opportunity to sate demand for tea in the West. The Portuguese began purchasing tea from Guangzhou and supplying it to British and Dutch merchants until the mid-1700s.

When the Qing dynasty reopened to foreign trade, the British established direct links with Guangzhou and grew increasingly dominant in Asia. And while the British eventually monopolised the tea market, Macao continued to play an essential role as an intermediary port until Hong Kong came into the picture and became the duty-free port of choice for European ships.

However, Macao’s role in developing tea culture in the West did not end there. In the early 19th century, the Portuguese empire shipped a wide variety of seeds – from avocado to mango, grapefruit, camphor, lychee and more – from Macao to Brazil, which was a Portuguese colony at the time. After the seeds acclimated, the Portuguese planted them to create the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro in 1811. A year later, Macao Senator Rafael Botado de Almeida sent seeds of the Camellia sinensis (the shrub that produces tea leaves) to Rio de Janeiro followed by Chinese farmers in 1814, who cultivated a tea plantation in the garden and harvested the leaves twice a year.

Although the tea trade slowed during the next century, Macao saw another “golden age” for tea in the 1940s and ‘60s. During this period, tea house culture gained popularity in Macao with famed tea houses – Lok Kok, Kun Nam and Iun Loi – gracefully dotting historical Rua de Cinco de Outubro and the surrounding neighbourhood. Lo explores Macao’s vibrant tea house culture in one chapter by examining an order sheet from Va Mau tea shop. On the sheet, over 60 kinds of teas were available to consume, which the expert believes demonstrates the city’s high standards during this era.

In the 1970s, however, tea house businesses started to decline as many locals sought employment in the burgeoning textile and clothing industry, and a wider variety of dining outlets – such as Western-style franchises, Chinese-style hot pot and seafood restaurants – emerged in the city.

“A great number of tea houses began to close down to give way to urban development – the current site of Kun Nam is a hotel, and Iun Loi a supermarket,” says Lo, emotional about the loss. “Many have forgotten the thriving tea culture in Macao. I am trying to look for the golden age of Macao in the ruins [through the metaphor of a broken door].”

Life begins with tea

When working on the 500-page book, which took Lo about a year to write, the tea master combed through research, notes, photos and references. In particular, he relied on his notes from previous business trips to the mainland, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea and reference books, such as Macao Brief Monograph and the Macao Encyclopaedia, co-authored by Wu Zhiliang, president of the Macao Foundation, and scholar Ieong Wan Chong.

“Due to the pandemic, many of my lectures and workshops had to be put off. So I wrote like clockwork every day,” says Lo of his writing process.

Apart from charting tea’s journey from the mainland to Macao, the expert also shares stories about running Chun Yu Fang and promoting tea culture beyond Macao. For example, in 2001, he was asked to perform a tea ceremony in Japan. To the guests’ surprise, Lo pulled out the equipment he had designed himself and demonstrated his unique tea ceremony style, which he says was warmly received by the guests. After the experience, Lo recalls feeling delighted to be able to share his designs with other enthusiasts and spread Macao’s tea culture abroad.

Inspired by classical writings, such as Ch’a Ching (《茶經》) by the respected Sage of Tea Lu Yu, Lo handmakes his wooden tools and designs porcelain teacups, kettles and scoops, which he then has made in a Chinese kiln. He elaborates on his tea-making tools in his book while sharing helpful tips for choosing suitable teacups, lids, kettles, spoons, ladles and more.

After years of exploring, teaching and researching tea, the subject has become an integral part of Lo’s life. Every day, he savours tea, arranges flowers to go with his tea ceremonies, handmakes tools and hosts gatherings. In addition, he gives lectures on his ceremony designs and the history of tea to his students at local secondary schools, Macao Polytechnic Institute’s Seniors Academy and Chun Yu Fang. His teaching, research and books are all part of his mission to sustain local tea culture and inspire the next generation while expanding his well of expertise.

“When I wrote about Chun Yu Fang, a wave of memories came over me. I thought about the customers who spent their afternoons appreciating tea here. I was sometimes angry as our culture had been underestimated,” says Lo. “An excruciating feeling gripped me, as my profession and passion were once criticised [as insincere]. However, whenever I reminisced about how I have grown professionally and became recognised, I felt grateful.”

Find Lo’s books (available in Chinese only) at local bookstores: Macau Plaza, Universal Gallery & Bookstore and Elite Book Store.