TEXT Joaquim Magalhães De Castro

Portuguese traveller writes his memoirs on China in his literary sensation Peregrinação published in 1614

The latest studies by historian Jin Guo Ping, the translator of Peregrinação into Chinese and one of the top experts in historical relations between China and Portugal, have corroborated much of what the 16th-century Portuguese adventurer Fernão Mendes Pinto wrote about the Middle Kingdom (China), a subject occupying nearly two‑thirds of his famous memoirs.

Mendes Pinto (c.1509 – 1583) is the author of Peregrinação (Pilgrimage), a literary sensation published posthumously in 1614. Beyond recounting his many adventures, the book offers an European’s view of Asian, and especially Chinese, civilization at the time.

Mendes Pinto travelled to India in 1537 and spent the next two decades in Asia, much of it in the Far East, often in the service of the Portuguese crown. In 1543, he claimed to have landed at Tanegashima Island in Japan, supplying the local ruler with an arquebus and thereby introducing guns to that country. Then in China, he was convicted at one point of plundering royal tombs and sentenced to a year of hard labour on construction of the Great Wall. In 1558, after his return to Portugal, Pinto wrote Peregrinação.

The traveller settled in Almada near Lisbon, married, received a royal pension, and died 25 years later in 1583. His memoirs, a demy quarto volume containing more than 400 pages divided into 226 chapters, became widely popular with several new editions published in the 17th century.

“… I undertake this crude and rough writing, which I leave to my children… so that they can see in it the travails and perils of life I experienced in twenty‑one years during which I was thirteen times a captive and seventeen times sold, in the parts of India, Ethiopia, Arabia Felix, China, Tartary, Macassar, Sumatra and many other provinces of that oriental archipelago at the ends of Asia…”

Misfortune lands Pinto in China

During his travels between 1540 and 1550, along the coast and upriver, Mendes Pinto generally expresses admiration and sympathy for the Chinese people and their culture.

During his travels between 1540 and 1550, along the coast and upriver, Mendes Pinto generally expresses admiration and sympathy for the Chinese people and their culture.

Fernão Mendes Pinto entered Chinese territory as the result of a tragic shipwreck. He lived, though he could hardly have imagined the difficulties he and the other survivors would face.

The territory they landed in, likely somewhere on the coast of Jiangsu province, was unknown to the survivors. They set out walking over hills and dales before eventually finding shelter at a local inn, where they presented themselves as poor shipwrecked subjects of the King of Siam. They were immediately provided with all the assistance they required, as that kingdom was a vassal of the Celestial Empire and habitually employed foreigners in its service. In such shelters the stay was limited to three days, so they once again took to the road, though not before they were provided with ample supplies by the local inhabitants. They soon reached another shelter for travellers, where they were provided with food, lodging, laundry service and even medical assistance, for some of them were quite ill.

Foreigners at that time were only allowed to trade in the ports, and were forbidden from entering Chinese territory. Fearing contact with imperial authorities, they decided to travel on secondary roads, with limited success. They would go on to be arrested, mistreated, and considered as thieves on various occasions. Such hard times alternated with good luck when they received alms or found shelter with local Chinese families, a unique opportunity to closely observe habits and customs different from their own. Mendes Pinto and his companions were among the first Europeans to have that privilege.

The Portuguese traveller also had the opportunity to witness China’s vastness, vividly recounting the bustling waterfront of the long canal and the ports where they docked when travelling by boat. The variety of products on sale in markets and fairs and the skill shown by the Chinese in breeding animals and cultivating land were two aspects that stood out for Mendes Pinto, who assures us that “in that Empire of China there were as many people living along the rivers as in the cities and towns.”

At one moment during his trip, he calls attention to a city with noble and rich buildings and “bridges sustained on very thick columns of stone and roads all paved with very fine flagstones, and all very large and well‑finished and very long,” a description that fits the profile of the former capital, Hangzhou. His sense of astonishment before the many marvels he witnessed is evident throughout the text.

Mendes Pinto states that of all the cities he knew, none could be compared to “the great Peking,” lauding its grandeur and sumptuousness

Exploring the Grand Canal

There is no definitive proof that he visited Suzhou, as the names of places he passed through are generally hard to identify. Even today the names for places and regions of China can seem confusing due to the different spellings used. This is especially true in the south of the country, where Cantonese and various other dialects are present. So when Fernão Mendes Pinto speaks of a “good city surrounded by a very fine and strong stone wall, with towers and bastions almost like our own and a quay bordering the river,” he could be referring to Suzhou just as easily as any other city along the Grand Canal.

In one of the chapters of his book, he mentions a small city with a large number of bridges “made on very strong stone arches, and at the ends columns with their chains crossing through and stone benches so people could rest,” a description which perfectly recalls Zhouzhuang. It could also refer to Tongli, though, a neighbouring canal city that has resisted the passage of centuries in the Grand Canal region encompassing the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang.

Peregrinação is a veritable treatise on sinology. In it, Mendes Pinto highlights on several occasions the richness of the streets, even the most ordinary ones, all of them very long and broad “with fine smooth paving”. He speaks of a land “fertile in food, so rich and well‑supplied in all things” that he can find no words to describe them. He also describes numerous warehouses stocked with an endless variety of food and places where “all kinds of game and meat as are created on this earth are slaughtered, salted, cured, and smoked.”

His account details the dynamics of trade practiced in ordinary shops of rich merchants, “which on their private streets were very well‑arranged, with such a quantity of silks, embroidery, fabrics and clothing of cotton and linen, and furs of martens and ermines, and of musk, fine porcelains, items of gold and silver, seed‑pearls, pearls and gold in powder and bars, so that we nine companions were continually amazed.” And where there was trade there were also “technical officials for as many vocations as there are in the guilds.”

Mendes Pinto highlights the ability and ingenuity of the Chinese “in all mechanical dealings and agriculture, and the very skilled architects and inventors of very subtle and artful things,” and records the presence of men and women who played various instruments “to provide music to whoever wanted to listen, and for that reason alone become very rich.”

To the Forbidden City

It is not certain that Fernão Mendes Pinto ever visited the Chinese capital, and some scholars staunchly reject that possibility. Whether or not he did, it is certain that what he recounts is very close to reality. If he did not actually visit the empire’s capital, he was certainly very well informed about it.

He describes a city with “noble streets with arches at the entrances and gates which closed at night,” noting that “most of them have fountains of very good water and are by themselves very rich and finely worked,” and mentioning the “hundred and twenty noble squares,” each of which hosted a market fair every month.

Mendes Pinto states that of all the cities he knew, none could be compared to “the great Peking,” lauding its grandeur and sumptuousness, due to its “superb buildings” and “infinite wealth, superlative abundance, well‑supplied in all things necessary, countless people, trade and vessels, justice, government and peaceful court.”

Even so, the centre of all attention remains the Forbidden City, which at the time, “as the Chins told us” it had 360 entrances, all permanently guarded by four men armed with halberds, “to control everything that passed through.”

He notes a certain class of odd and influential people, telling us that “within the walls of the royal palace are a hundred thousand eunuchs” along with 12,000 guards, “whom the king provides with large salaries and pensions,” and describes the concubines, which he numbers at 30,000. They were surely attractive women, for beauty was no rarity in the kingdom of China. On several occasions Mendes Pinto highlights that fact, stating that Chinese women were “very pale and chaste, and inclined to all work more than the men.”

He stresses the importance of the temples, which were usually surrounded by beautiful gardens, noting the admirable carpentry work of the buildings and the walls of the enclosures “lined inside by very fine porcelain tiles and above by roof ridges and in the corners by very tall spires, diversely painted.” He also mentions triumphal arches in gold with a large number of silver bells hanging by chains of the same metal, which “ringing continuously due to movement of the air made such a noise that it was impossible to hear anything else.”

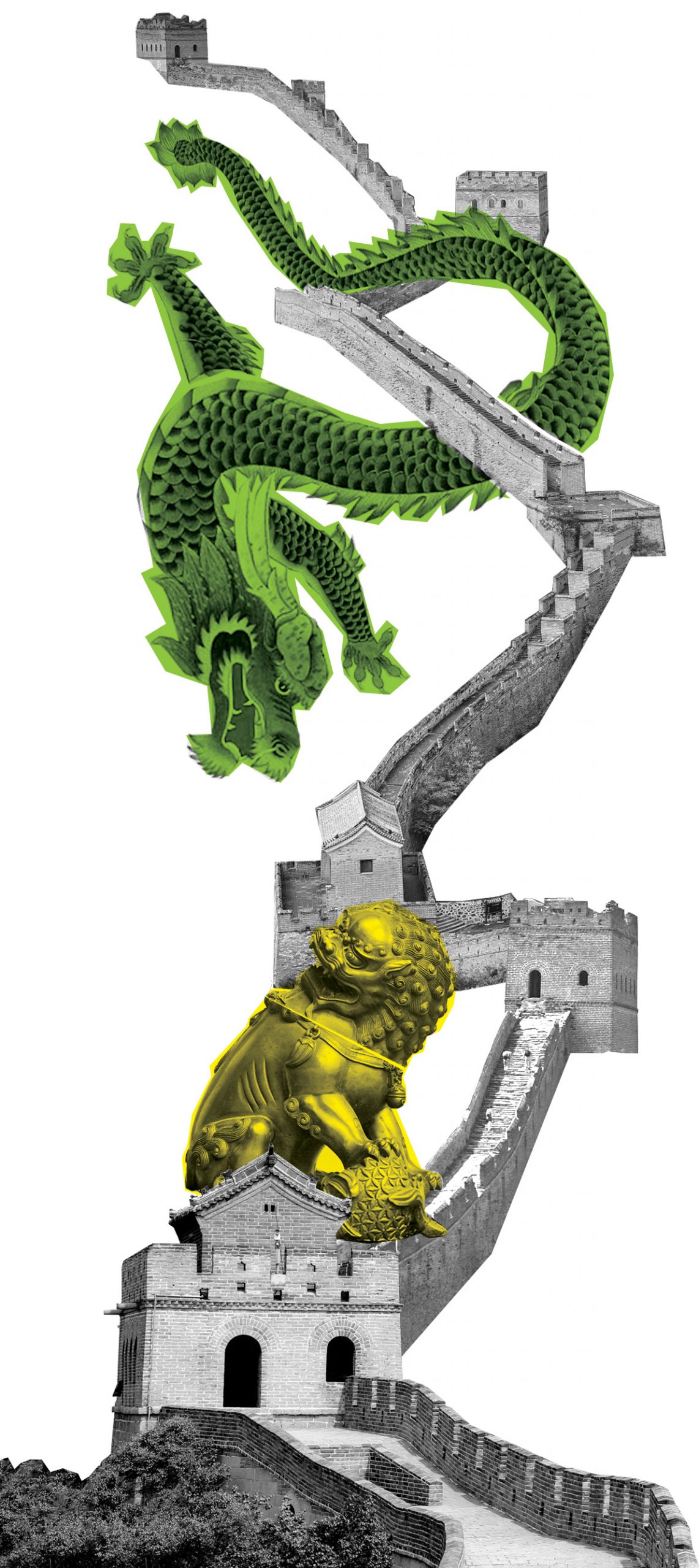

Of course, Mendes Pinto cannot fail to notice the golden lions on round balls or spheres, which he correctly calls “the emblem or arms of the king of China.” Another imperial symbol is the dragon, appearing to his eyes as nothing more than a monster, with the “figure of a dissembling serpent,” recalling to him the figure of Lucifer.

Revealing the Great Wall

Fernão Mendes Pinto was one of the first Europeans to reference the existence of the Great Wall, telling us that “the king who then reined in China,” fearful that the traditionally nomadic barbarians in the north would once again unite, he ordered that the entire border between the two empires be protected by a wall.

Fernão Mendes Pinto was one of the first Europeans to reference the existence of the Great Wall, telling us that “the king who then reined in China,” fearful that the traditionally nomadic barbarians in the north would once again unite, he ordered that the entire border between the two empires be protected by a wall.

Pinto specifies that, according to historical annals, “in twenty‑seven years the entire border of those two empires were closed from end to end.” After making the respective calculations, he concludes that the wall was 315 leagues long and more than 750,000 men were involved in the project.

His has perhaps the most complete description of the Great Wall ddone by a Westerner of that time and date.

In Peregrinação, Fernão Mendes Pinto collected descriptions and rare geographical details about the many countries he had known. In it, some kingdoms disappear, while others merge or change names, making it difficult to accurately trace his truly audacious route, with its numerous maritime diversions along the coast of the Asian continent, travelling up rivers and visiting islands.

While mindful of the illusory style, likely intended to better combine the author’s personal history with the accounts of others, it is still fascinating to revisit some of the places mentioned in the book. Especially China, the country to which he devotes the most pages, full of praise for its “very great order and marvellous government” – a powerful kingdom, exotic and perfectly organised. The rigorous and profoundly just Chinese social organisation ran from the distribution of work for all to the free right to justice, including subsidies for the “lame and people without support” and homes for the elderly no longer able to work. Even the shelter offered to him and his companions demonstrated how advanced China was in the area of social assistance, administration and application of justice, compared to Europe at the time. For even as his many fanciful adventures challenge credulity, the immense admiration for China and its people expressed by Fernão Mendes Pinto rings remarkably true.