TEXT Mark O’Neill

To coincide with the launch of a new biography written by his grandson, we look at the life and times of Pedro José Lobo.

Pedro José Lobo was one of the most important figures in the modern history of Macao. He headed the Economic Affairs Department for 27 years, negotiated with the Japanese during World War Two to feed thousands of starving people and managed a gold monopoly that made him a fortune.

And now – due to the love and affection that many people in Macao still have for him – the first biography on the great man, who died aged 73 in 1965, is to be published by his grandson, Marco Lobo. The consultant and writer, who has lived in Tokyo for the past 20 years, says that ‘something would have been lost’ if he had not put pen to paper and documented his grandfather’s colourful life.

Pedro Lobo was, with businessman and politician Ho Yin, one of two shadow Governors of Macao in the mid-20th century. They conducted difficult and complex negotiations with the Japanese military and the Chinese government as the Portuguese governors lacked their knowledge, experience and language skills – their time in Macao was a stepping stone in a long career in the colonial service, so they were happy to entrust some of their duties to the two men. But, despite this life of politics, gold and business, Pedro Lobo’s early days were just like any other little boy’s living in a Portuguese-speaking country far from the shores of the motherland.

Island beginnings

Pedro Lobo was born on 12 January, 1892, in Manatuto, Timor-Leste, which was then under Portuguese authority. He had Chinese and Portuguese blood and his adoptive father was a doctor, Belarmino Lobo, a native of Goa who had moved to Dili, Timor-Leste’s capital, becoming vice-mayor and then mayor of the city.

In 1902, at the age of nine, Lobo travelled to Macao and became a boarder at St Joseph’s Seminary. There he became fluent in Portuguese and he also spoke Cantonese and English. Many Portuguese people in Timor-Leste – also known as East Timor – sent their children to Macao because, in short, they believed its schools were better.

The story of my grandfather, Pedro Lobo, is very complex, with truth mixed with fiction.

Marco Lobo

“My grandfather greatly enjoyed his years at St Joseph’s,” says Marco Lobo. “Among the things he learned was musical composition. After graduation, he did not want to return to East Timor. He felt part of the community in Macao. After spending 30 years in East Timor, his father Belarmino retired to Goa.”

After graduating, Pedro Lobo became a teacher of mathematics at Escola do Pedro Nolasco before joining Banco Nacional Ultramarino (BNU), where he worked for seven years, learning about currency and money. On 16 October, 1920, he married Branca Helena Hyndman in Hong Kong and they had six children – three boys and three girls. He joined the Macao government in 1927 and worked in the Economic Affairs Department, rising to become its director in 1937, a position he held until his retirement in 1964.

The war years

The Second World War, however, was a period of great difficulty for Pedro Lobo, as it was for Macao and the rest of the globe. “It was a very delicate time for Portugal, whose most important historical ally was Britain,” says Marco Lobo. “Like Portugal, Macao would only remain independent if it was useful to everyone. It was like Lisbon and Casablanca – a centre for spying. A place where everyone could read international newspapers.”

“Macao had to be friendly to everyone,” continues Marco Lobo, “including the Japanese and the rich Hong Kong businessmen who moved there. The Japanese opened a consulate there in 1939.” Macao’s population at the time tripled to 450,000 because of the refugees from Hong Kong and the Mainland who flocked to the only place that was not under Japanese occupation. There was not enough food and other necessities. Hundreds starved to death.

“Every morning, people saw corpses on the streets,” says Marco Lobo. “They became used to it. Governor Gabriel Teixeira used all the revenue from the gaming and the opium concessions to procure food. The stability of the pataca was critical. It was made the official currency.”

Diplomatic and generous

Marco Lobo says that his grandfather kept in contact with all the different players in Macao, including the two foreign consuls – Japanese and British – and was extremely well informed. Sometimes, says Marco Lobo, his grandfather ‘had to keep secrets from Governor Teixeira’ so that if the governor ‘was asked by the Japanese, he did not know’. “It was a dangerous time,” admits Marco Lobo. “Grandfather was only four foot, seven inches tall. He used it to his advantage – he did not appear threatening to anyone.”

On behalf of the government, Pedro Lobo – who donated generously to support hundreds of penniless refugees who had taken refuge in Macao – nationalised all the food in the city’s private businesses and warehouses. He bought at market price products like rice, cereals and tinned goods and stored them in government warehouses. To obtain more supplies, he set up the Macao Cooperative Company, which was one third owned by the Macao government, one third by the Japanese army and one third by several rich businessmen, mostly from Hong Kong. It managed the trade between the city and the Japanese, who controlled the import and export of goods, including the food.

On 16 January, 1945, US bombers attacked petrol warehouses in the Outer Harbour – the petrol there was to be sold to the Japanese that day. Pedro Lobo had negotiated the deal and was in the warehouse at the time. He ran to his car and was machine-gunned but managed to survive by abandoning the car and throwing himself to the ground.

The golden years

In the late 1940s, while keeping his official post, Pedro Lobo went into business on his own account with several associates and set up the Heng Chang Company in 1948. One of the associates was Ho Yin, the leader of the Chinese community, which was apt as Lobo was the leader of the Macanese community.

The firm’s main business was gold trading, which turned out to be extremely lucrative. Portugal did not sign the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, which, in an effort to stabilise the global economy after the war, fixed the international price of gold at US$35 an ounce. The Macao government effectively gave Heng Chang a monopoly on gold trading.

The company imported gold, legally, to Macao. Officially, it was not supposed to be exported. But, in reality, many people bought gold at a rate of up to US$70 an ounce. The decade after 1945 was a tumultuous one for Chinese people at home and in Southeast Asia, so many bought gold as a financial security.

In 1948, Pedro Lobo set up the Macao Air Transport Company (MATCO) which served the route between Macao and Hong Kong. Gold arrived in Hong Kong from different countries but could not be sold there because Britain had signed the Bretton Woods Agreement so, every Saturday, a MATCO plane left Hong Kong for Macao carrying plentiful amounts of gold.

This gold trading business made Pedro Lobo, who was also a director of the Macao Water Supply Company, and his associates extremely rich – and it also brought a substantial income to Macao’s government, which levied a tax on the trade. It also made Lobo a media star – he even appeared in ‘Life’ magazine. In 1959, British author Ian Fleming – the man behind the famous James Bond spy novels – interviewed him in Macao. Ever since Fleming’s iconic ‘Goldfinger’ novel came out, some believe the author based the titular villain on Lobo – a man with a Midas touch.

The siege resolver

Pedro Lobo played a key role in resolving a dispute between Macao and the Mainland government in 1952. After the outbreak of the Korean War, the Western powers imposed a trade embargo on the PRC but Macao remained a point of entry and exit for Chinese and foreign goods. From May to July 1952, there were small-scale armed conflicts between Portuguese and Chinese soldiers at Portas do Cerco on the northern tip of the Macao Peninsula. The border between the two sides was not well defined.

In July, China imposed a blockade on land, sea and river trade with Macao, causing a major shortage of basic goods – mainly food. In August, however, Pedro Lobo led intense negotiations with the Chinese side to resolve the issue. He offered his personal regret for the incident and the Macao government paid a small amount of compensation to the Chinese victims of the shootings. China lifted the blockade on Macao after Lobo had displayed his excellent diplomacy skills in his part as a crucial player in the skirmish’s peaceful resolution.

The culture vulture

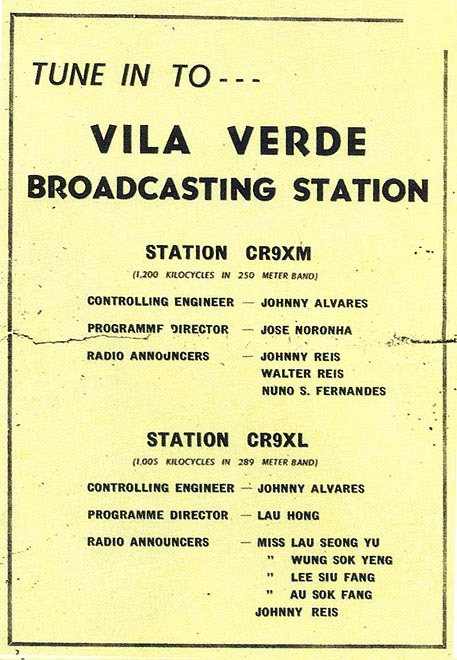

In 1950, Pedro Lobo set up Macao’s first commercial radio station, Radio Vilaverde, which was named after his own home where the studio was located. Back then, he supported the station financially and it broadcast in Portuguese and Cantonese. Lobo, who wrote musical compositions and directed operettas, also set up the Vilaverde Orchestra – and there used to be a radio programme each day broadcasting its works.

That same year, Pedro Lobo also set up the Macao Musical and Cultural Association ‘to promote the dissemination of art and culture, especially in Portuguese, and make Macao, in its many aspects, better known in Portugal, the colonies and all parts of the world where the mother tongue is spoken’.

Each month or quarter it published a cultural magazine ‘Mosaico’ in Portuguese, Chinese and English. He also set up the Euro-Asian Film Company, which produced Macao’s first film, a love story.

From 1959 to 1964, Pedro Lobo was president of Leal Senado – the Loyal Senate of Macao. He was also a member of the Holy House of Mercy and of the Congregation of Our Lady of Fatima, which brought devotees to the shrine in Portugal. In 1952 and 1964, he received awards from the Portuguese government – the Commander of the Order of the Colonial Empire and the Commander of the Order of Prince Henry.

Pedro Lobo donated generously to education and charity. He was a man of many talents as politician, businessman, artist and philanthropist. He died of illness on 1 October, 1965 in Hong Kong and was buried in the city’s Happy Valley cemetery, leaving behind his family and a plethora of memories with thousands of people, be it for his diplomatic war exploits, his golden touch or his devotion to Macao.

A life in words

Pedro Lobo – who has a street named after him next to Jardim San Francisco in Macao – was a colourful character who is about to have his life put into the pages of his grandson’s forthcoming biography.

“Fifty years after his death, people are still talking about him,” says Marco Lobo, who was born in Hong Kong in 1954, the sixth of 10 children, his father being famous businessman and politician Sir Rogério Hyndman Lobo. “[My grandfather’s] legacy is owned by the people of Macao. If I do not write this book, something will be lost. The more time goes on, the stronger I feel about this.”

“This will be my fifth book,” continues Marco Lobo, “all about the Portuguese diaspora. After nine months of work and six months of solid writing, I will deliver the manuscript in October to the Instituto Internacional de Macau. It is in English, the majority language of the Macao diaspora.”

Marco Lobo says that, in his younger years, he and his family would head to Macao during the holidays, weekends and the summer. “Grandfather lived in a large house which he named Vila Verde,” he says. “In the same street, there were six houses, three on each side. Each belonged to one of his children. There were goats in the street in those days. Vendors arrived with bread and other foods. The pace of life was very slow.”

My grandfather’s legacy is owned by the people of Macao.

Marco Lobo

Pedro Lobo lived in a complex that included his house, his office and the radio station he founded – a site that is now dominated by supermarkets and shops at the junction of Rua de Francisco Xavier Pereira and Avenida do Ouvidor Arriaga. “I did not know him as a maker or shaker but as a grandfather,” says his grandson. “After breakfast each day, all of us grandchildren went to see him in his ante-room. He was in casual clothes or a dressing gown. He gave us all 10 to 20 patacas every day. He was very generous. We would jump into a pedicab and go to the toy shop. We talked to him in Portuguese and English.”

Marco Lobo notes that his grandfather was, at the same time as being fun, a stern disciplinarian, demanding that his grandchildren study hard. “This was a result of the training he had received from his own father and the St Joseph’s Seminary,” he says. “He knew all about each one of us and what we were doing. He corresponded with my mother. I still have those letters. He died in 1965, one year after his retirement.” In March last year, Marco Lobo returned to Macao to attend the city’s annual literary festival and people asked him about writing the biography. “Ours is a very private family,” he says. “The story of [my] grandfather is very complex, with truth mixed with fiction. Initially, I did not want to do it. But I changed my mind when I realised the affection people still felt for him.”

Marco Lobo’s biography on Pedro Lobo – which is as yet untitled – has been commissioned by the International Institute of Macau. It is expected to be published by the end of this year. See lobomarco.com/2019/08/19/pedro-jose-lobo for more details.