Once forgotten, the culture, art, architecture and history of China’s Western Xia region is brought to life in a Macao Museum exhibition that runs until next month. We take a look at what makes this region a ‘glorious’ Chinese cultural and historical treasure.

What do you know about the ancient Egyptians? You’ve at least heard of pyramids, mummies and the curse of Tutankhamun. You’re also probably familiar with the Romans and their armies, the Greeks and their philosophy, the Aztecs and their temples and the Mongols and their fierce warriors. When it comes to China, you’ve surely heard tales of the emperors, the inventions and the revolutions. But what do you know about Western Xia? Unless you’re a historian or scholar, probably not much.

And this would hardly be a surprise. For hundreds of years, little was known about this ancient civilisation that dominated vast swathes of land in northern China. However, now, with the help of historians on the Mainland, the world is beginning to learn more about one of China’s most ‘glorious’ civilisations.

Macao, over the past couple of months, is one such place that has been learning about Western Xia. ‘Reminiscences of the Silk Road – Exhibition of Cultural Relics of the Western Xia Dynasty’ is an exhibition that has been on show since June 14 – and runs until October 6 – at Macao Museum. It’s been organised in collaboration with the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Museum – which is based in Ningxia, a small autonomous region in north-central China that is at the heart of what was once Western Xia – and celebrates this year’s 20th anniversary of Macao’s return to China.

The exhibition takes visitors around 148 relics from the ancient culture and features a film that details its history, as well as an array of interactive exhibits. If you enter with no idea about Western Xia and its people, then you will leave with an excellent potted history. But it may be worth boning up beforehand…

The birth of a civilisation

Wind the clock back nearly 1,000 years. Western Xia stretches out to the harsh sands of the Gobi Desert in the north, the Xiao Pass in the south, the Yellow River in the east and the Pass of the Jade Gate in the west – covering a region that is now populated by Ningxia, as well as Gansu province and eastern Qinghai, northern Shaanxi and northeastern Xinjiang, and parts of Mongolia. This is a huge land, spread out over 310,000 square miles – bigger than France and the US state of Texas. You could fit modern Macao into the region 6,982 times.

Western Xia was founded by the Tanguts, a Sino-Tibetan tribal union that moved to northwest China some time before the 10th century. They spoke the Tangut language, one of the ancient Qiangic languages. The Tang Empire ruled China for most of the years between 618 and 907. However, in the late ninth century it was weakened by the Huang Chao rebellion, which was spearheaded by smuggler Huang Chao and eventually failed in its aim but caused chaos across much of the Middle Kingdom. In 881, however, the Tanguts assisted the Tang in suppressing the rebellion and, as a reward, Tangut general Li Sigong was granted the three prefectures of Xia, Sui and Yin as hereditary titles. This is a key moment as, from here on, the Tanguts had a base from which to expand their realm southwest towards their old homelands.

In 1002, more than 40 years after China fell under the rule of the Song Dynasty, the Tanguts conquered Ling Prefecture, setting up their capital of Xiping there, and by 1036 they had annexed the Guiyi Circuit, an area headquartered in Shazhou Prefecture and containing Shazhou city – which is now Dunhuang in Gansu province – and even pushed into Tibetan territory, conquering Xining, now the capital of Qinghai province. Thus, with the lands in place, the Tanguts proclaimed the state of Western Xia in 1038. Dr Tai Chung Pui, assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong’s School of Chinese, says: “The Tanguts were a hugely important people in China at the time and when they proclaimed the state of Western Xia, they were powerful, influential and proud.”

The founders of the Western Xia dynasty could be said to be Li Jiqian or his son, Li Deming. Li Jiqian was the leader of the Tanguts but died in battle in 1004, so his eldest son became leader – and, for the next 20 or so years, he was a great figurehead, considerably expanding the Tanguts’ territory. But he was hardly a conservative ruler and allowed his people to absorb the Chinese culture that surrounded them as well as allowing them to keep their original identity as Tanguts.

In 1028, Li Deming, who died in 1032, named his son Li Yuanhao as crown prince. Under his rule, Western Xia was officially founded – thus, he is most aptly described as its founder. Li Yuanhao was more conservative than his father, so he sought to restore and strengthen the Tangut identity by ordering the creation of an official Tangut script. He made Xingqing – now Yinchuan city, the capital of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region – the capital city of Western Xia and he also instituted laws that reinforced traditional Tangut customs, such as making his people wear traditional ethnic clothes. “Li Yuanhao,” says Dr Tai, who has written papers on Western Xia, “also made men shave their heads or, at least, have short hair – but it is still a point of debate as to whether this practice was a Tangut tradition or was created from this point to show off their unique identity.”

The end of an era

The Mongols and one of the most famous leaders in global history are heavily involved in the story of Western Xia – or, at least, its end. In the 13th century, Genghis Khan, who had unified the northern grasslands of Mongolia, led his troops into many attacks against Western Xia. It was during this final round, in 1227, that the land of the Tanguts was overrun and the Mongols devastated its buildings and written records. Much was burned to the ground. Tens of thousands of people were massacred, included the last Tangut emperor.

Genghis Khan also died in Western Xia, during the fall of Yinchuan in 1227. His death remains a mystery – some say he died of an illness, others say he fell from his horse. Some legends even say he died from a wound that was inflicted in the final battles. Whatever the cause, one of the most famous leaders in world history perished in Western Xia. And Western Xia itself was also no more – this vast once-prosperous region and its unique civilisation becoming largely forgotten for centuries.

During the 20th century, however, archaeologists and historians began to unearth documents and relics in great numbers which show the Tanguts’ spiritual life, demonstrate their wisdom and vivify the unique charm of Western Xia’s culture. This includes its square, sophisticated writing characters, its magnificent Buddhist architecture and its stone carvings. These discoveries have allowed scholars to build up a picture of the Tanguts and their culture, as well as a picture of what life must have been like in Western Xia. Dr Tai says: “These documents and relics unearthed in the 20th century are mostly from Khara-Khoto, a Tangut city in what is now Inner Mongolia. It was a thriving centre of Western Xia trade in the 11th century and historians are so grateful that it has given up so many secrets and relics about the Tanguts.”

And that forms the basis of the exhibition at Macao Museum. Loi Chi Pang, museum director, says: “This themed exhibition of relics primarily showcases the archaeological finds in the Western Xia region. A fine selection of 148 pieces offers a compendious interpretation of the Western Xia civilisation, with some rare items making their first appearances outside the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region.”

The history of Western Xia is so glorious that its cultural uniqueness is worth of deep understanding.

Loi Chi Pang

“The pieces,” continues Loi, “include examples of the language and printing techniques in Western Xia, as well as Buddhist scriptures and statues. There are also goldwares, woodwares and glazed artistic examples of pottery, as well as eaves tiles – known as ‘wadang’ – and stone architectural statues.”

So far, according to Loi, since its inauguration on 14 June, the exhibition has attracted more than 40,000 people. “We hope that,” he says, “by means of showcasing the Western Xia relics, the public can understand more about Chinese history. The culture of Western Xia is a part of Chinese history and its uniqueness fully demonstrates that worldwide cultural diversity existed in China for a very long period. The history of Western Xia, in fact, is so glorious that its cultural uniqueness is worthy of deep understanding.”

Speaking the lingo

One of the sections in the exhibition that demands attention is the display of Western Xia’s Tangut language. Building on the historical foundation of Chinese characters, the Tangut script from Western Xia includes about 6,000 logographs and was created by scholar Yeli Renrong around 1036 under Li Yuanhao’s ordain.

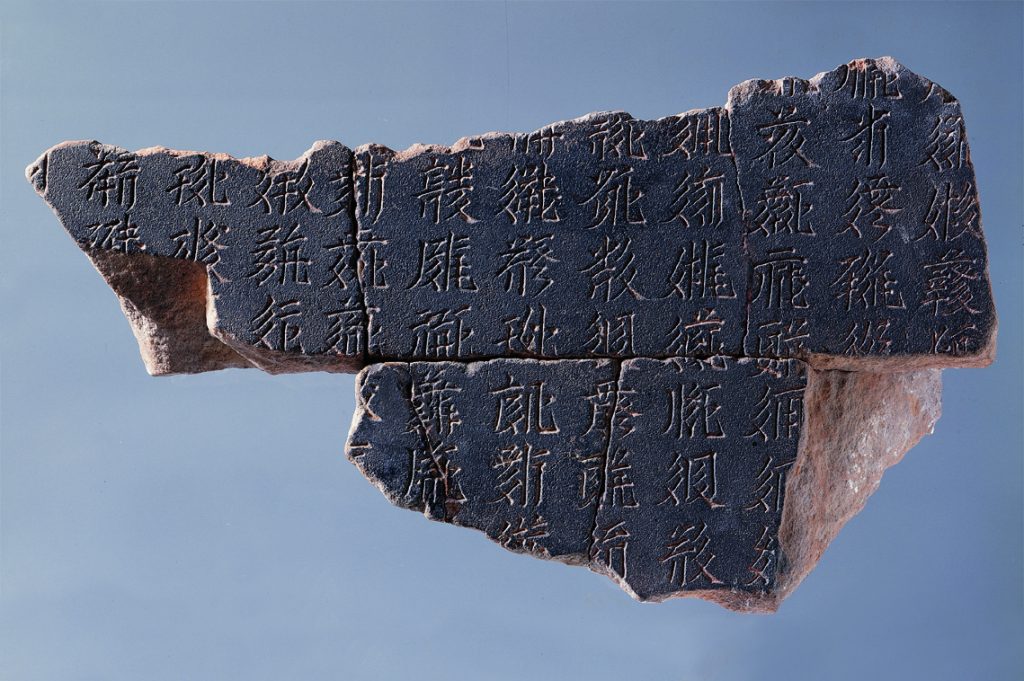

In terms of their composition, Tangut characters can be classified into ‘simple-component’ and ‘compound’ and constitute a rather complete system and regulation. Loi says: “Each character has a square-shaped complicated structure with balanced left-and-right vertical proportions, consisting of many presses and throws. The Tangut language was widely used for official documents, laws, judicial records and trade contracts, as well as literature, history scrolls, dictionaries, stele – stones or wooden slabs – inscriptions, seals, talismans and translations of Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist scriptures.”

“The Tangut language,” adds Loi, “was used throughout the entire Western Xia period. Even after the state was defeated, the language continued to be used until the mid-Ming Dynasty in some areas.” The Tangut language lay dead for many centuries but in 1804, Qing Dynasty scholar Zhang Shu discovered the previously unknown writings on the ‘Restored Stele of Gantong Pagoda of Huguo Temple in Liangzhou’ were, in fact, Tangut – and the language was once again exposed to the world.

Remnants of steles have been found in what was once Western Xia and one excellent piece is on show at the exhibition in Macao – the ‘Remnant stele with Tangut characters from the Shouling Imperial Tomb’. Ruins of sixteen stele pavilions, having been looted many times, were found in nine mausoleums of the Western Xia Imperial Tombs, the royal mausoleums located near the eastern slopes of the Helan Mountains, about 35 kilometres away from Yinchuan City. The remnants of the steles found here are severely broken, mostly with only three or five characters. Those with more than a dozen are rare.

So the ‘Shouling’ remnant in the exhibition is special – it pieced up with five fragments to become the one that contains the most Tangut characters. The inscription of the stele in 11 lines and 44 Tangut characters is in regular script with balanced structures that show adept engraving skills. All the characters are painted with gold – and some gold remains.

Incredible tombs

The Western Xia Imperial Tombs near to the Gobi Desert perfectly represent the Tangut culture. They are the best-preserved historic cultural heritage that the civilisation left behind, occupying an area of some 50 square kilometres and including nine imperial mausoleums, 271 subordinate tombs and one site of a large architectural complex. The tiered tomb walls and high towers make for a magnificent sight.

Many of the relics on show in Macao hail from these mausoleums. One of the most striking is the parcel-gilt bronze ox that’s lying down with knees bent and eyes peering into the distance, which was unearthed from No M177 imperial tomb in Yinchuan city in 1977. “It was produced through many crafting processes,” says Loi, “such as smelting, moulding, casting, polishing and gilding, showcasing Western Xia’s high-level bronze castings and epitomising Western Xia’s metal artistry.”

“Named the ‘eastern pyramids’,” says Loi, “Western Xia’s Imperial Tombs not only inherit the tradition and architectural techniques of the Han and Tang dynasties in the Central Plain but they are also integrated with the depth of nomadic culture and so they present a unique architectural style with regional and ethnic characters. Whether in size or momentum, the tombs epitomise the art of Western Xia’s architecture.”

Art and architecture

There are many artistic and architectural pieces on display at the exhibition. Black, white and brown are the major colours of Western Xia ceramics – and they are often decorated by coloured dots or floral patterns. The Tanguts created many artistic ceramics in Western Xia, as well as goldwares, silverwares, bronzewares and ironwares – and textiles such as silk and damask. Then there are intaglio pieces – such as a highlight piece on display: a rectangular carved bamboo intaglio which is incised with a scene of people’s everyday life in the Central Plain. This is surmised to be a treasurable item from the cultural exchange between Western Xia and the Song people.

As for Western Xia architecture, decorated with beautiful and rich patterns, ‘wadang’ tiles and drip tiles are most common. “Western Xia’s architectural relics comprise primarily of pagodas, mausoleums, temples and architectural parts,” says Loi. “Its architecture, on the one hand, adopted different styles of the Central Plain and, on the other, was influenced by Tibetan Buddhism. Their shapes, structures and ways of building were full of variety.”

Loi says much work was done with experts from Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Museum in the curation of the exhibition. “It took no less than one year to curate the exhibition of Western Xia history,” he says. “Many colleagues in Macao Museum – in the collection, education and relic preservation sections – were engaged in the process of organising it and selecting the relics. Besides this, the Ningxia museum gave us tremendous support in every aspect of the curation, such as providing the background historical information, allocating human resources when we were creating the installations and helping to organise educational activities.”

The Silk Road

Western Xia occupied the area around the Hexi Corridor, a stretch of the Silk Road – the most important trade route between China and Central Asia. “Western Xia has been – and still is – an important historical symbol of the ancient Silk Road,” says Loi. “The creation of its splendid culture benefitted from the most valuable exchanges among ethnic groups and exhibited the loftiest aspirations [of the Western Xia people] in its time.”

Loi says that Macao and Ningxia are, respectively, located ‘at the pivot of the Maritime Silk Road and the Silk Road’. “They have also undergone long-lasting historical transformation,” he adds, “contributing to the unique and splendid civilisation created by cultural encounters and exchanges. After more than 900 years, Western Xia’s artefacts still carry on its historical mission of exchange and are exhibited in Macao, a trade port that enjoys more than 400 years of history on the Maritime Silk Route. They exude new charm in the new era and will give us a more straightforward and more in-depth understanding of the Silk Road in history.”

Reminiscences of the Silk Road – Exhibition of Cultural Relics of the Western Xia Dynasty is on at Macao Museum until 6 October. The museum, at Mount Fortress, is open from 10am to 6pm each day, except Mondays.