The painter and architect George Smirnoff first arrived in Macao in early 1944. By the end of 1945, he was gone. In that brief tenure, the Russian-born artist produced a celebrated series of watercolour paintings that captured the essence of everyday life in Macao – work that preserved a period of contrasts. As World War Two raged beyond the neutral city’s borders, as neighbouring Hong Kong fell under the yoke of Imperial Japan, Smirnoff championed Macao’s tranquillity. Its seascapes, churches, plazas and people.

Today, Smirnoff is hailed as a pioneer of modern art in Macao. His work is recognisable to many, having winged its way around the world in the form of postcards and postage stamps. Tiny representations of the city he was, perhaps, happiest in. But this ostensible success shrouds a troubled life. Despite his talent, the painter was often penniless, under duress or forced to live as a refugee. Time and again, he had to uproot and relocate, from Russia to China, then Hong Kong and eventually Macao. He never put down roots; he never knew true financial security. Smirnoff died in Hong Kong, in 1947, before his 45th birthday.

While geopolitical turbulence seemed to dog him wherever he went, Smirnoff managed to find a window of peace in Macao. The quietude is reflected in his enduring artistic legacy.

An itinerant life

Born Yuri Vatilievitch Smirnoff in 1903, Smirnoff later went by ‘George’ (an anglicised version of Yuri). He grew up in Vladivostok, a bustling port on the Sea of Japan. In 1917, Smirnof and his mother left their homeland for neighbouring northern China, where they eventually settled in Harbin.

The Russian language was widely spoken in the Manchurian city at that time, including at schools and universities. Smirnoff himself was an excellent student and went on to study architecture at Harbin Polytechnical University. He married and had his first child, Irene, in Harbin. In early 1930s, Smirnoff and his young family left to Qingdao on China’s eastern coast.That’s where Smirnoff began building his career. He found work as an architect and drew plans for hundreds of residences. The work was largely seasonal. In the summer, when building demands were highest, he would draft architectural projects. The rest of the year, he would paint. Watercolours were his speciality and before long, people started buying his artwork.

Imprisoned in Hong Kong

As the Japanese Imperial Army marched south, Smirnoff felt the need to up sticks yet again. This time the family relocated to Hong Kong. By the late 1930s, Smirnoff was working as an architect in the city. He was employed by Marsman and Co., a mining company that contributed to Hong Kong’s air raid precaution scheme through tunnel building. But Smirnoff also joined the local artists’ guild and helped to organise exhibitions.

Then, in 1941, Japan occupied Hong Kong. Later that same year, the artist was arrested for suspected espionage by the Kempeitai, military police unit within the Japanese Imperial Army.

While Smirnoff was not found guilty of espionage, the police found bottles of bootlegged vodka in his home. That was enough of a crime to earn a stint in Hong Kong’s Stanley Prison. Even without Smirnoff’s imprisonment, however, life for his family was hard in Hong Kong. The artist’s daughter, Irene Smirnoff-Garfinkle, recalled it as “a form of limbo” in the foreword to the Hong Kong-based historian Jason Wordie’s 2013 book, Macao. Smirnoff-Garfinkle passed away in late 2023 at the age of 88, in the US.

After Smirnoff was released from prison under an amnesty agreement, American bombers destroyed the house his family had been living in. It was the final straw: “Macao was the only place we could go,” wrote Smirnoff-Garfinkle.

Making a mark in Macao

She and her father were the first of their now five-member family to make the journey to Macao. Back then, the crossing took four hours by ferry. “We arrived in Macao with virtually nothing, except what little we could carry with us,” Smirnoff-Garfinkle recalled. Their first home in the then-Portuguese-administered city – which remained neutral throughout the war – was at the grand Bela Vista, one of Macao’s first foreign-style hotels. Once a luxury property overlooking the Praia Grande, the Bela Vista had become a makeshift shelter for war refugees.

After Smirnoff’s wife, Nina, and two younger children arrived, the family moved into the top floor of a house in Pátio das Seis Casas – which still stands today, near the Mandarin’s House. This was the start of a year-and-a-half chapter that Smirnoff-Garfinkle described as “almost the only time in his life that my father was truly at peace with himself and his surroundings”.

“We had nothing of any material substance. But our family was intact, the people of Macao were wonderful to us and generously gave all kinds of help and support, and we had food on the table every day,” she said. “For once, after all our lives in China, war and disorder hadn’t followed us.”

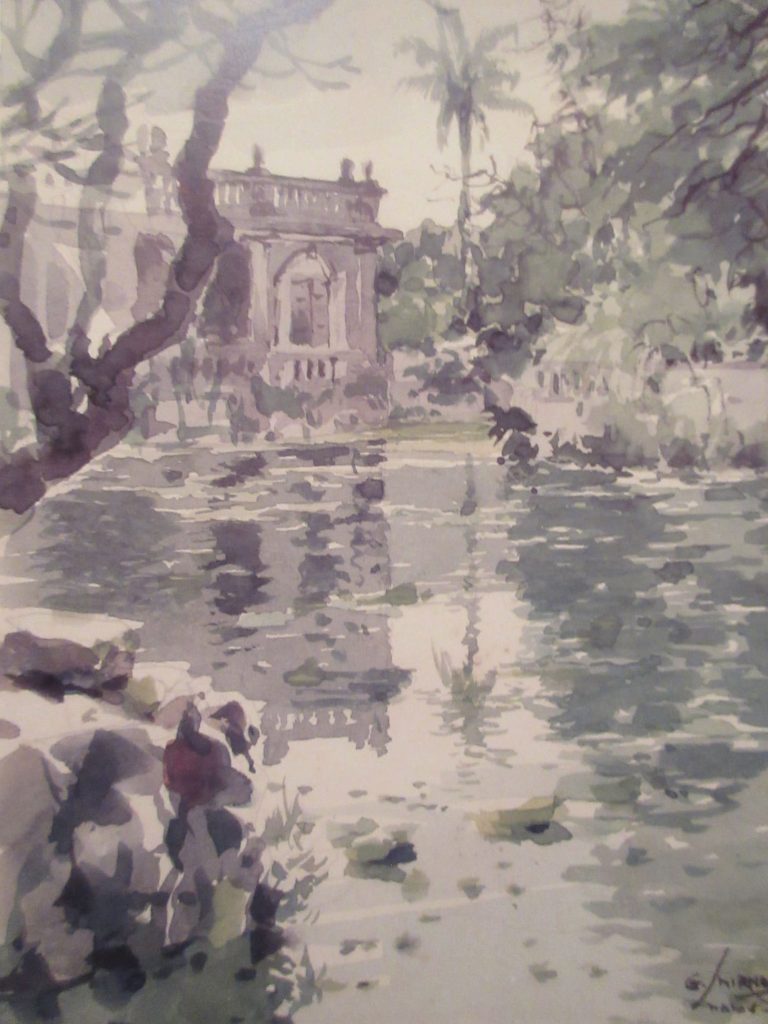

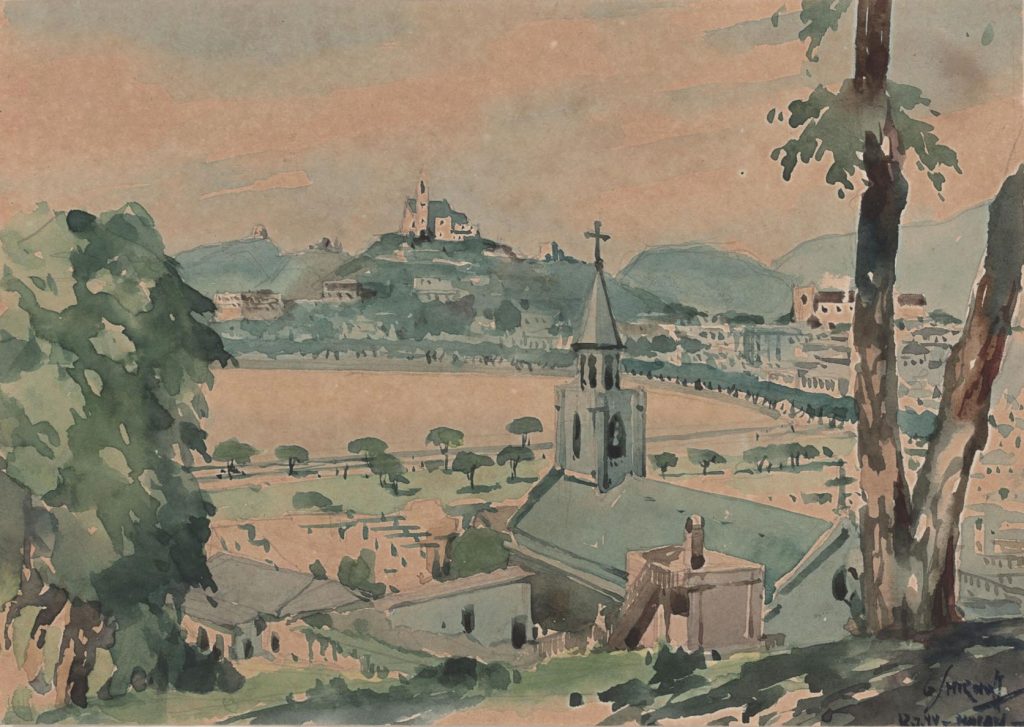

Relative peace didn’t equate to an easy life, however. The influx of refugees meant jobs and everyday resources were scarce in Macao. Unable to find work as an architect, Smirnoff made money teaching private art classes and designing theatre sets. In his free time, Smirnoff-Garfinkle remembered her father roaming Macao extensively on foot, memorising the scenery. By night, he painted what he had seen. “If you matched what he painted to the real setting, it was almost like a photograph,” his daughter wrote.

His skill and sensitivity as an artist eventually caught the attention of Dr Pedro José Lobo, a prominent political figure in Macao. Lobo commissioned Smirnoff to produce a series of watercolours depicting Macao’s urban landscapes – the aim of which was to create a permanent pictorial record of the city, according to Wordie’s book.

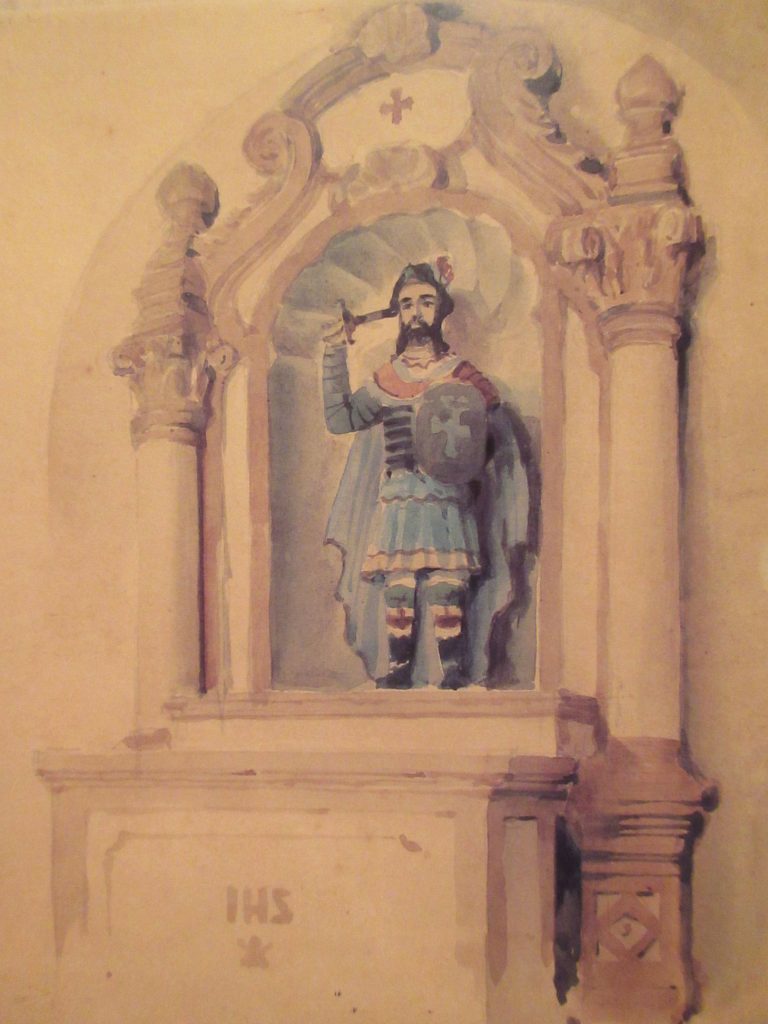

The project yielded dozens of delicately daubed paintings that, today, evoke a sense of nostalgia for 1940s Macao. His artistic style leant itself to capturing the crumbling facades of the city’s splendid churches, yet he depicted its people and animals with sweetness, too. Smirnoff’s Macao series was considered a great success and, over the years, has featured on many postage stamps and postcards.

In 1945, Smirnoff returned to Hong Kong to rejoin the Public Works Department. He took his own life just two years later. The artist was buried in Hong Kong’s Happy Valley cemetery, an ironic resting place considering his tumultuous life.

Most of Smirnoff’s watercolour collection is now in storage at the Macao Museum of Art, as the original paintings are considered too fragile to be part of a permanent exhibition. Reproductions of his work are on display at Café Bela Vista, built in homage to the original hotel that Smirnoff briefly lived in.

As a nod to Smirnoff’s lasting impact on the city, the Macao SAR government has produced a map that allows people to follow in the artist’s footsteps. It includes places he painted, lived and worked. The map’s text honours Smirnoff as “the Father of Modern Art of Macao”.