Club Lusitano, one of Hong Kong’s oldest private clubs with a history of 151 years, has over 500 members, of whom 270 are active.

Two walls of floor-to-ceiling crenulated windows afford spectacular views of the shining skyscrapers of Hong Kong, overlooking the home and office of Chief Executive Carrie Lam on one side and the HSBC building on the other. One wall displays two stanzas from the epic work Os Lusíadas by Luís Vaz de Camōes, for whom the room is named, while the other features a massive world map depicting the routes taken by pioneering Portuguese explorers and mariners. Above it all, a ceiling of glittering starlight lovingly recreates the star charts that guided these adventurers centuries ago.

Welcome to the grand ballroom of Club Lusitano, one of Hong Kong’s oldest private clubs with a history of 151 years. Located on the 27th floor of a clubowned building on Ice House Street, the Salão de Nobre Camões reflects a history in which members take great pride. Club Lusitano, a name derived from the ancient Iberian Roman province of Lusitania, restricts its membership to people of Portuguese heritage.

“We have over 500 members, of whom 270 are active. The rest do not live in Hong Kong,” said Patrick Rozario, club president since 2014 and an accountant by training, noting that the club is currently recruiting new members.

The club occupies the top six floors in the building, with a restaurant, bar and lounge, billiard room, library, an office, and a small chapel in addition to the ballroom. O Retiro, the quiet chapel located above the ballroom, is home to a number of religious statues including a copy of Our Lady of the Milk from Braga and Our Lady of Fátima.

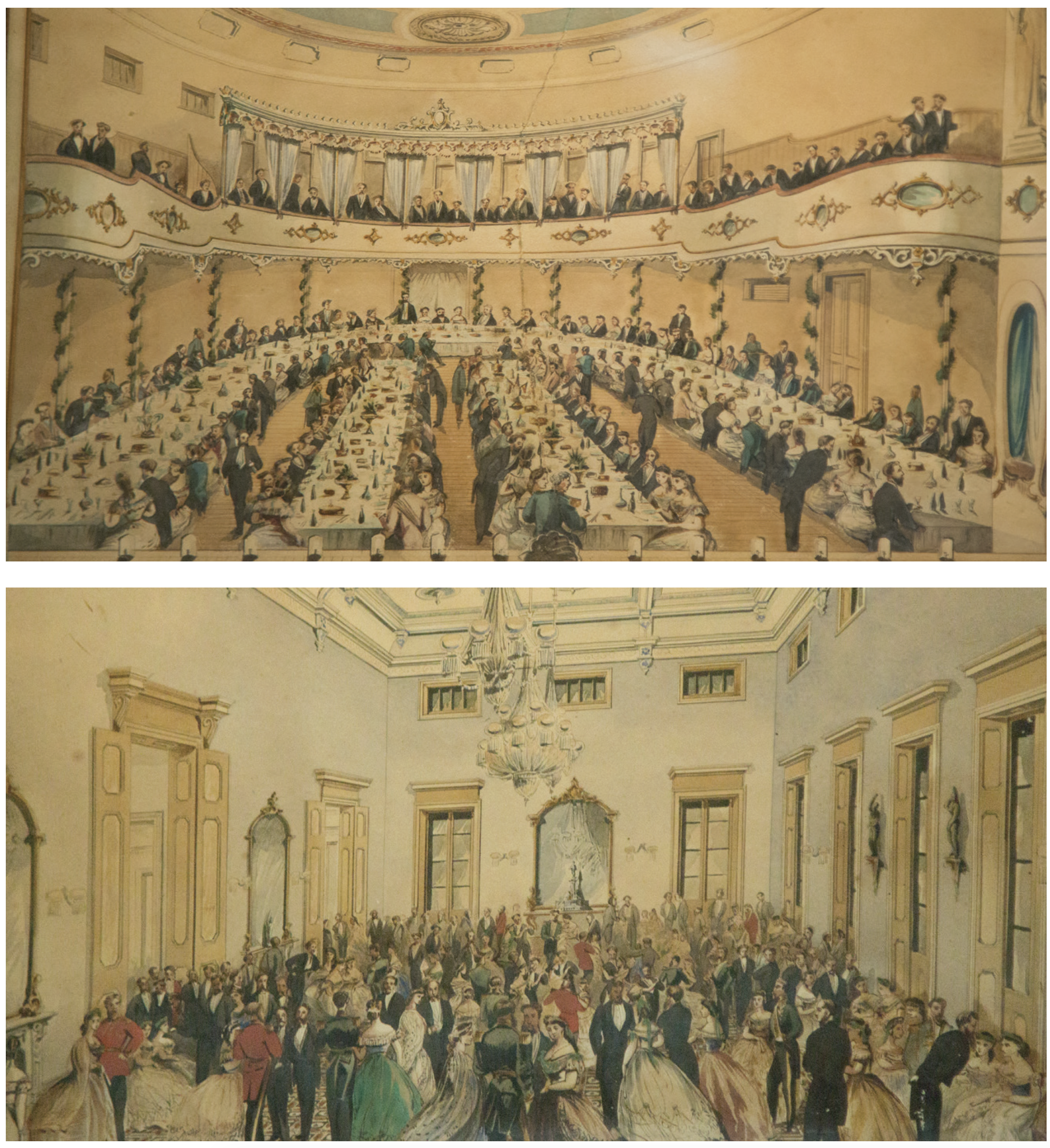

The social club hosts many annual events, from festivities for Portuguese National Day and Fésta de São João in June, to a newly created, blacktie End of Year Gala Ball and a Christmas lunch in December. They also invite celebrity chefs for special dinners, organise movie screenings and talks, and host music and reading events.

The club’s membership reflects the Portuguese diaspora, with members from Australia, China, Canada, Brazil and the UK, as well as Portugal. To join, a person must provide proof of Portuguese ancestry or nationality. Acquiring such proof is aided somewhat by neighbouring Macao.

“Macao never had a major conflict, so its records, including its church documents, are intact,” Rozario explained. “There are also shipping records that show the arrival of ships from Portugal. People often use these to prove their heritage.”

Despite their shared Portuguese heritage, most members do not speak the language. The primary language in the club is English, although many members speak Cantonese.

Cycle of history

Like many members of Club Lusitano, Rozario is Macanese. “My first Portuguese ancestors arrived in Macao in the 1750s, inter‐marrying with different nationalities and later arrivals from Portugal,” he said. “I grew up in Hong Kong and remember going to Macao for christenings, weddings, and birthday parties.

Rozario left for education in Canada at 15 years old, and eventually became an accountant. He worked in Canada and the US before returning to Hong Kong in 1996. “I wanted to see the handover,” he said. “My parents and brother live in Toronto. I rejoined the club and have many schoolmates here.”

Many like Rozario have returned to Hong Kong since the handover, joined by young people from Portugal and Brazil in search of economic opportunities. “In seeking new members, we are reaching out to these people. In the past,” Rozario explained, “we did not have to try very hard. Everyone from Hong Kong knew each other.”

Rozario’s story echoes the odyssey experienced by many members of the city’s Portuguese community since the 1960s when instability, violence, and limited opportunity spurred mass immigration to English‐ and Portuguese‐speaking countries. Now many are returning, breathing new life into a club so central to the history of Portuguese in Hong Kong.

Early cultural centre

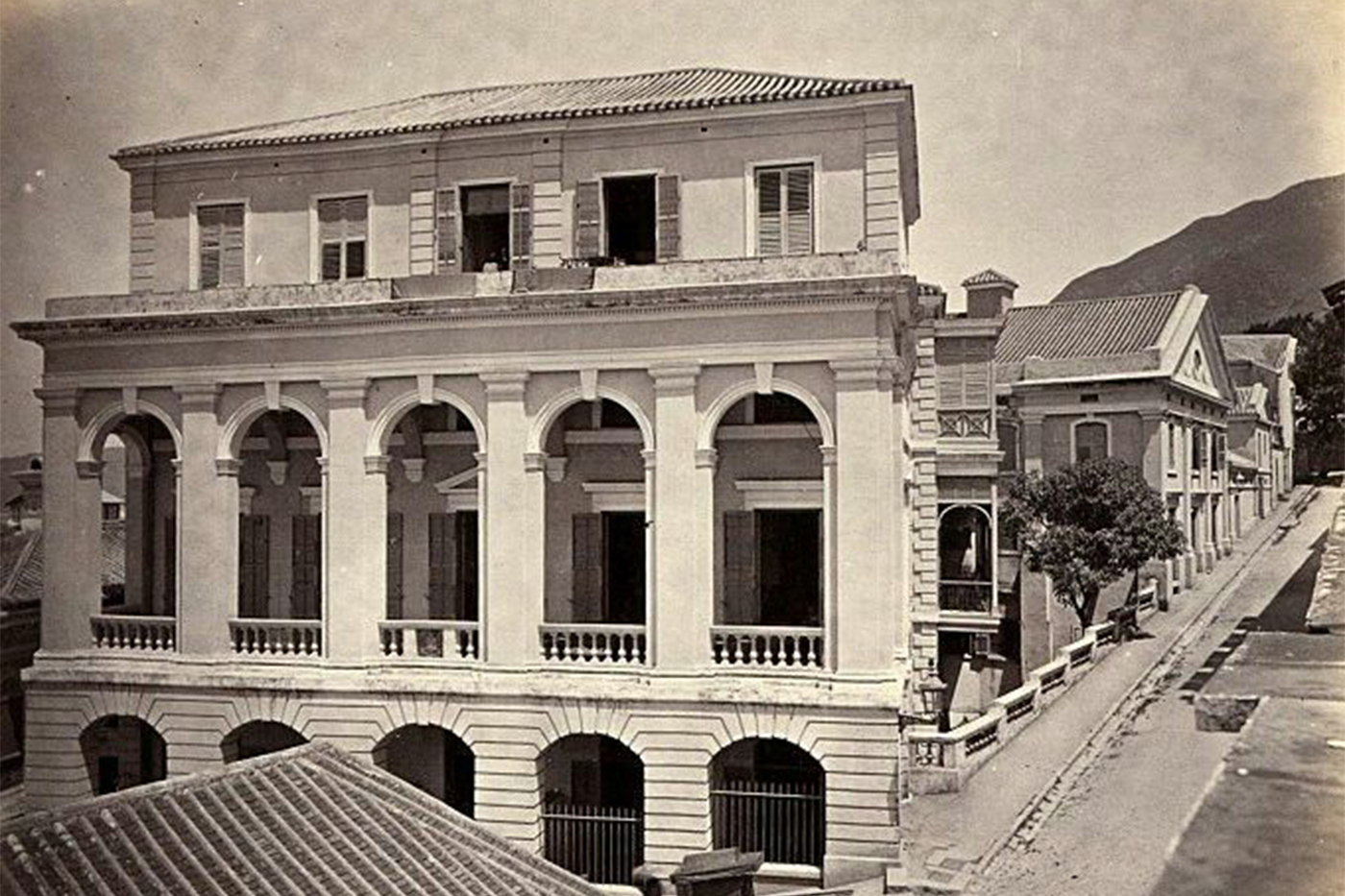

The club opened 17 December 1866, financed in large part by JA Baretto and Delfino Noronha, two prominent members who covered three‐quarters of the construction costs for the large property on Shelley Street in the Mid‐levels district of Hong Kong island.

In a neighbourhood home to many Portuguese who had left Macao in search of economic opportunity, the club served as a centre for culture and community. It included a large reception room and library, several meeting rooms, and a theatre – the venue for all performers in the colony before the City Hall Theatre opened in 1869.

The balls, theatre performances, and official ceremonies hosted by the club contributed greatly to the integration of the Portuguese community into the British colony. As did the generosity of the small community, which largely funded the club and made significant contributions to the establishment

of early Catholic institutions in the city, from the Canossian Mission, built in 1850, to the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, completed in 1888.

The Lusitano Challenge Cup, an annual horserace organised by the Lusitano Club, is even older than the club itself. Then called the Lusitano Cup, the inaugural race was held at Happy Valley Racecourse in 1863, and renamed in 1866, the year of the club’s founding. Still held today, this class 3 race covers 1,400 metres on the track at Sha Tin Racecourse with prize money of HK$1 million (US$127,970).

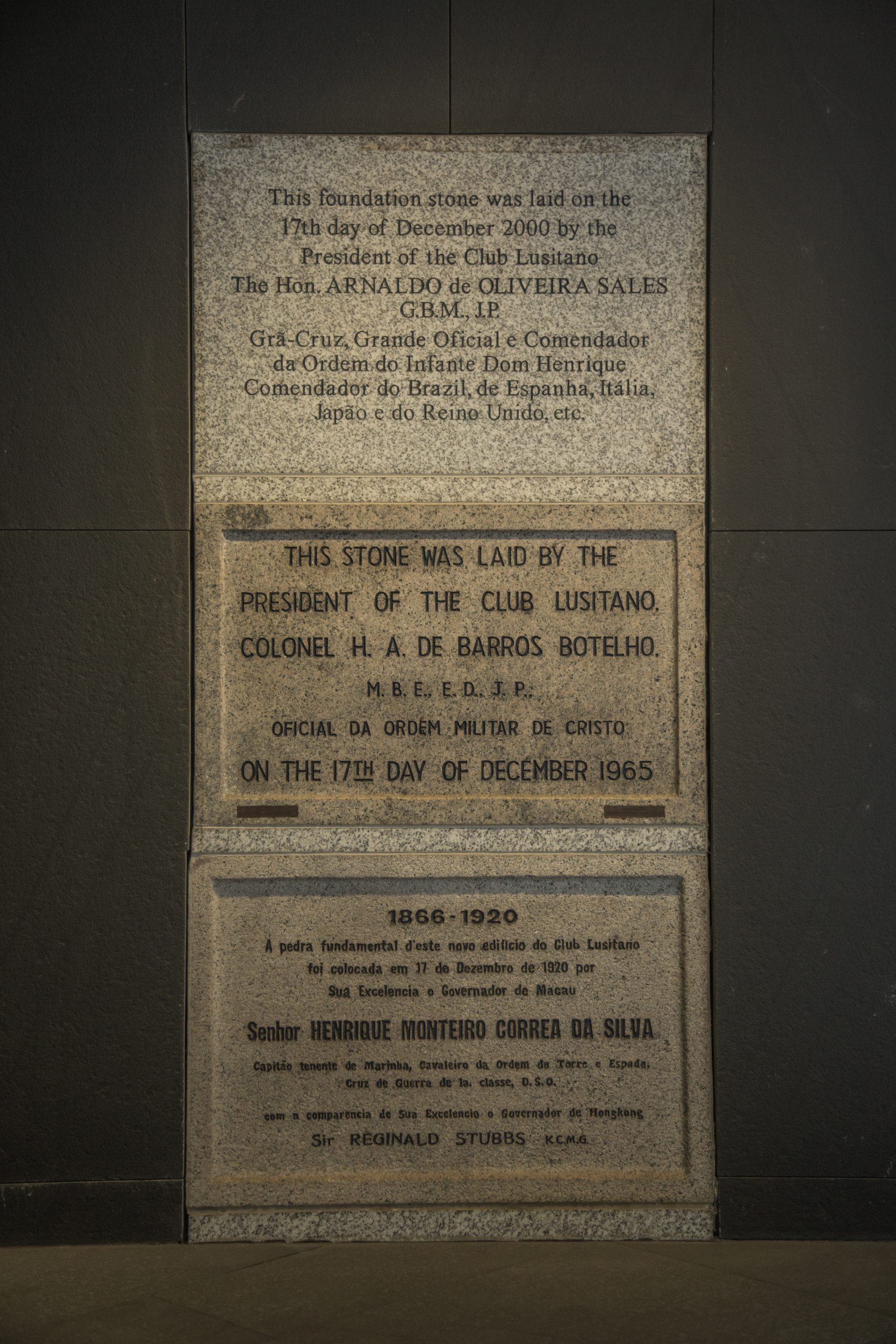

On 17 December 1920, exactly 54 years after completing the original club, they laid the foundation stone of a new site at 16 Ice House Street, where the club still resides today. The property was purchased by a member, AML Soares, then sold to the club at cost. The governors of Hong Kong and Macao attended the ceremony – unsurprising given governors, military personnel, and overseas delegations had frequented the club for decades.

The men’s club maintained strict rules regarding dress and members’ conduct, and developed a reputation for its high standard of billiards, bridge, and other card games. AJ Osmond, the then billiard champion of Hong Kong, hit a break of 267 at the club in March 1925. More than 90 years on, the record still stands.

The most famous member of the club during this era was José Pedro Braga. The grandson of founding member Delfino Noronha, Braga began his career in his grandfather’s printing press. He served as managing director of the Hong Kong Daily Telegraph and spent decades as a Reuters’ correspondent in the colony before leaving journalism. The successful businessman worked closely with the Kadoorie family, and in 1929, he became the first Portuguese appointed to the Legislative Council where he served until 1937.

A refuge in wartime

World War II greatly impacted the club and the Portuguese community it served. When the Japanese attacked in early December 1941, the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps mobilised to protect the city. The corps counted many club members among its ranks, and one company made its headquarters in Club Lusitano until Hong Kong surrendered less than a month later.

In the dark years that followed, the club became a refuge for the Portuguese community, providing shelter and rations to many. While Portuguese neutrality in the war lent Club Lusitano some protection, they were still subject to raids by the Japanese secret police, who accused them of spying for the British.

Carlo Henrique Basto, arrested in 1942 during a bridge game with friends, was convicted on the basis that the notes he wrote while playing bridge were coded messages. By September that year, he was dead, beheaded in Stanley.

In the brief battle for Hong Kong, 31 Portuguese lost their lives and many others were interned

for their service in the Volunteer Defence Corps. Hundreds worked as forced labourers in squalid conditions in labour and PoW camps. In 1949, the Portuguese government bestowed the Ordem Militar de Cristo on the club in recognition of its distinguished service during the war.

Changing world hits Portuguese in Hong Kong

The Portuguese community in Hong Kong grew rapidly in the post‐war period, reaching over 10,000 by the mid‐1950s. Many returned from Macao, where they’d taken refuge during the war, while others were fleeing the mainland after the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949. Membership expanded and Portuguese played a prominent role in government, commerce, sports, and the professional sphere.

For all their progress, local Portuguese still faced extensive and institutionalised discrimination that made good economic opportunities scarce. Those who did break through faced a glass ceiling in the large British banks and companies, and in the government.

World War II greatly impacted the club and the Portuguese community it served. The club became a refuge for the Portuguese community, providing shelter and rations to many.

With executive positions reserved for British and European expatriates, local Portuguese spent years working in firms with little hope of reaching top positions. A rare exception was Leonardo d’Almada e Castro, QC, who served as a member of the Executive Council and became the first Portuguese King’s Counsel.

In 1964, the club demolished their building on Ice House Street and replaced it with a 12‐storey structure designed by Macanese architect Alfredo V Alvares. Club Lusitano occupied the top five floors, more than 1,000 square metres in total. They leased the lower floors to the Philippines‐based Equitable Bank; subsequent tenants included the Hong Kong government and Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation. Rents provided 95 per cent of the club’s income, enabling it to keep down costs and membership fees.

But the golden era of the Portuguese community in Hong Kong was already drawing to a close. The entire region felt unstable: the Korean and Vietnam wars, the bitter political campaigns in mainland China and violent 1967 riots in Hong Kong and Macao. People looked overseas for a safer, more secure future for themselves and their families.

A trickle of Portuguese emigration became a flood by the 1970s. Club membership declined from the 1950s until the early 2000s as many left for Canada, Australia, Portugal, Brazil and the US, establishing sister clubs and Casas in their new homes. Those who stayed played a prominent role in the run-up to the 1997 handover. Sir Roger Lobo, who served as a member of the Executive Council between 1967 and 1985, led a crusade to protect Hong Kong rights during handover negotiations between China and the UK.

Comendador Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales spent nearly 30 years in the Urban Council, serving as its first chairman between 1973 and 1981. He is responsible for the building of many public swimming pools and other sporting facilities still in use today. As president of the Sports Federation and Olympic Committee of Hong Kong, he oversaw the participation of the Hong Kong delegation in the games.

At the 1972 Munich Olympics, Oliveira Sales risked his life by confronting armed Palestinians holding the Hong Kong, Israeli, and Uruguayan teams hostage, and successfully secured the release of his team. In the end, 11 Israelis and a German policeman died at the hands of the Palestinian attackers before German police were able to subdue them, killing five.

The club’s bar, broadly considered the heart of Club Lusitano, bears his name.

A new era

In 1996, the club building was demolished and replaced with a 27‑storey high‑rise, designed by Macao architect Comendador Gustavo da Roza and completed in 2002. Below the top floors occupied by the club are 20 floors of office space and a three‑level ground floor retail podium. A three‑storey Cruz de Cristo sits atop the building, recalling the early Portuguese ships which bore the distinctive, equal‑armed red cross as a symbol of their faith.

In 2016, the club celebrated its 150th anniversary with a week‑long celebration of Portuguese cuisine and a black‑tie gala ball. Having marked this major milestone, the future of Club Lusitano looks bright: membership has expanded with the admission of women members, the return of many Macanese from overseas, and more Portuguese nationals.

“In 2018, we will renovate the whole club,” said Rozario. “We will reopen the library and probably knock down the wall separating it from the bakery. That way you can read while sipping a coffee and enjoying the fragrance of the bread.”